テストステロン

テストステロン

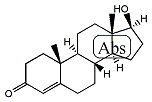

| 分子式: | C19H28O2 |

| 慣用名: | テスレン、ススタノン、テステロン、テストリル、テストロン、ビロルモン、オレトン-F、テストバース、ホモステロン、ビロステロン、プリモテスト、オルキステロン、テストステロン、メルテスタート、プリモテストン、ペルクタクリン、Teslen、Testryl、Oreton-F、Sustanon、Testrone、Primotest、Testerone、Testobase、Virormone、Homosteron、Mertestate、Orquisteron、Primoteston、Virosterone、Percutacrine、Testosterone、17β-Hydroxyandrost-4-en-3-one、アンドロリン、Geno-cristaux Gremy、Testviron T、テストステロイド、テストビロンシェーリング、サスタノン、ネオテスチス、アンドラソール、Testoviron Schering、Testosteroid、Sustanone、Neotestis、Homosterone、Andrusol、Androlin、ゲノクリストウックスグレミー、テストビロンT、(17S)-Testosterone、(17β)-Testosterone、Δ4-アンドロステン-17β-オール-3-オン、Δ4-Androsten-17β-ol-3-one、17β-ヒドロキシ-4-アンドロステン-3-オン、17β-Hydroxy-4-androsten-3-one、(17S)-17-Hydroxyandrosta-4-ene-3-one、グローミン、β-テストトテロン、β-Testosterone、β-テストステロン |

| 体系名: | 17β-ヒドロキシ-5β-アンドロスタ-4-エン-3-オン、17β-ヒドロキシアンドロスタ-4-エン-3-オン、(17S)-テストステロン、(17β)-テストステロン、(17S)-17-ヒドロキシアンドロスタ-4-エン-3-オン |

テストステロン

英訳・(英)同義/類義語:testosterone, androgen

精巣から分泌されるステロイド系性ホルモンで、性腺刺激ホルモンの刺激を受けて分泌される。雄の形質発現を進める。

| 化合物名や化合物に関係する事項: | チミン チロキシン チロシン テストステロン テトラサイクリン テトラサイクリン系抗生物質 デオキシリボシド三リン酸 |

Testosterone

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2025/10/04 07:13 UTC 版)

|

|

この記事には複数の問題があります。

|

Testosterone(テストステロン、1988年 - )は、日本の著作家、会社社長。

筋トレ革命集団DIET GENIUS代表、オンラインパーソナルGENIUS PERSONAL発起人、アスリートの為のメディアSTRONG GENIUS代表。

来歴

1988年生まれ。学生時代は110キロに達する肥満児だったが、米国留学中に筋トレと出会い40キロ近いダイエットに成功する。自身の人生を大きく変えた筋トレという文化を日本に広める事をライフワークとしている[1]。題して“日本筋トレ革命”。筋トレを通して日本の抱える問題の殆どを解決できると信じて行動している。DIET GENIUSの発起人であり代表。[要出典]大学時代に打ち込んだ総合格闘技ではUFCのトッププロ選手と生活をともにし、最先端のトレーニング理論とスポーツ栄養学を学ぶ[1]。 現在はとあるアジアの大都市で社長として働きつつ、[要出典]正しい筋トレと栄養学の知識を日本に普及し社会貢献する事に尽力している[1]。

著作

単著

- 筋トレが最強のソリューションである: マッチョ社長が教える究極の悩み解決法 (2016/01/29、ユーキャン)

- スーツに効く筋トレ (2016/12/22、星海社新書)

- 人生の99.9%の問題は、筋トレで解決できる! (2016/12/23、主婦と生活社)

- 筋トレライフバランス: マッチョ社長が教える完全無欠の時間管理術 (2017/04/07、宝島社)

- 筋トレビジネスエリートがやっている最強の食べ方 (2017/6/30、KADOKAWA)

- 筋トレで夢を叶える: 超一流のメンタルマッチョ養成講座 (2017/10/27、宝島社)

- 筋トレは必ず人生を成功に導く: 運命すらも捻じ曲げるマッチョ社長の筋肉哲学 (2018/01/23、PHP研究所)

- 筋トレ英会話: ビジネスでもジムでも使える超実践的英語を鍛えなおす本 (大岩秀樹監修。2018/07/01、祥伝社)

- ストレスゼロの生き方: 心が軽くなる100の習慣 (2019/11/01、きずな出版)

- 心を壊さない生き方: 超ストレス社会を生き抜くメンタルの教科書 (2020/06/18、文響社)

- ストレス革命: 悩まない人の生き方 (2020/08/28、きずな出版)

- 読むだけで元気が出る100の言葉 (2021/04/16、きずな出版)

- 大人も気づいていない48の大切なこと: キミの心をラクにするかんたんなヒント (2021/10/28、学研プラス)

- とにかく休め! ー休む罪悪感が吹き飛ぶ神メッセージ88(2024/2、きずな出版)

- 365日、絶好調で超ハッピーになれる言葉(2024/5、扶桑社)

- 筋トレが最強のソリューションである マッチョ社長が教える究極の悩み解決法 バルクアップ版(2024/5、ユーキャン)

共著

- 尻トレが最強のキレイをつくる (Miharuとの共著。2017/07/04、ユーキャン学び出版)

- 超筋トレが最強のソリューションである: 筋肉が人生を変える超・科学的な理由 (久保孝史との共著。2018/04/27、文響社)

- 筋トレ×HIPHOPが最強のソリューションである: 強く生きるための筋肉と音楽 (般若との共著。2018/12/14、文響社)

- 幸福の達人: 科学的に自分を幸せにする行動リスト50 (前野隆司との共著。2021/08/20、ユーキャン学び出版)

- Testosterone式 史上最強のダイエット (伊田暁人共著、2022/11、きずな出版)

- 「運動しなきゃ…」が「運動したい!」に変わる本(とうすけ共著、2023/5、ユーキャン)

コミック

- 筋トレ社長(原作:Testosterone、漫画:たむらあやこ。2017年、KADOKAWA、ISBN 978-4040692968)

脚注

- ^ a b c 『【 Twitterフォロワー数90万人超 】あの「筋トレ社長」ことTestosterone(テストステロン)氏の新刊書籍『ストレスゼロの生き方』を発売!』(プレスリリース)株式会社きずな出版、2019年11月8日。2020年4月27日閲覧。

外部リンク

- Testosterone (@badassceo) - X

- 筋トレで全て解決する社長Testosterone公式ブログ - Ameba Blog

- Testosterone (testosterone) - note

- Testosteroneのページへのリンク