公衆衛生

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2024/04/08 19:58 UTC 版)

歴史

18世紀まで

人類の文明の始まりから、コミュニティは、集団レベルで健康を促進し、疾病と戦ってきた[75][76]。健康の定義やその追求方法は、集団が持つ医学的、宗教的、自然哲学的な考え方、持っているリソース、生活している状況の変化によって異なっていた。しかし、初期の社会で、しばしば帰せられる衛生上の停滞や無関心を示したものはほとんどなかった[77][78][79]。後者の評判は、主に現代のバイオインジケーター、特に疾病伝播の細菌理論に照らして開発された免疫学的および統計学的ツールの不在に基づいている[要出典]。

公衆衛生は、ヨーロッパでも産業革命への対応としても生まれたのではない。予防的な健康への介入は、歴史的なコミュニティが痕跡を残したほとんどどこでも証明されている。例えば、東南アジアでは、アーユルヴェーダ医学とその後の仏教が、バランスの取れた身体、生活、コミュニティを約束する職業上、食事上、性生活上の生活様式を育んだ。この考え方は、中国伝統医学にも強く存在している[80][81]。マヤ、アステカ、アメリカの他の初期文明では、薬用植物市場の開催を含め、人口集中地域で衛生プログラムを追求した[82]。また、オーストラリアの先住民の間では、一時的なキャンプであっても、水と食料源を保存・保護し、汚染と火災のリスクを減らすためのマイクロゾーニングを行い、ハエから人々を守るためのスクリーンを使用するなどの技術が一般的だった[83][84]。

ヒポクラテス、ガレノス、または体液の医学体系を採用した西ヨーロッパ、ビザンティン、イスラムの文明も、予防プログラムを育んだ[85][86][87][88]。これらは、地形、風向き、日光への曝露などの地域の気候の質、人間と非動物の両方に対する水と食料の特性と利用可能性を評価することに基づいて開発された。医学、建築、工学、軍事マニュアルなどの多様な著者たちは、異なる起源と異なる状況下にあるグループにそのような理論をどのように適用するかを説明した[89][90][91]。これは重要であった。なぜなら、ガレノス主義のもとでは、身体の構成は、その物質的な環境によって大きく形作られると考えられていたため、そのバランスを保つには、異なる季節や気候帯を移動する際に特定の生活様式が必要とされたからである[92][93][94]。

複雑な、前工業化社会においては、健康リスクを軽減するために設計された介入は、さまざまな利害関係者の主導によるものだった可能性がある。例えば、ギリシアとローマの古代では、将軍たちは、20世紀までは大半の戦闘員が死亡した戦場の外でも、兵士の幸福のために備えることを学んだ[95][96]。少なくとも西暦5世紀以降、東地中海と西ヨーロッパ全域のキリスト教修道院では、修道士と修道女が、寿命を延ばすために明示的に開発された、栄養価の高い食事を含む、厳格ではあるがバランスの取れた生活様式を追求した[97]。また、王室、諸侯、教皇庁なども、しばしば移動することがあったが、同様に、占有する場所の環境条件に合わせて行動を適応させた。また、構成員にとって健康的だと考えられる場所を選択し、時にはそれらを改変することもあった[98]。

都市では、住民と統治者は、幅広い 健康リスクに直面する一般大衆のために、対策を講じた。これらは、初期の文明における予防措置の最も持続的な証拠の一部を提供している。多くの場所で、道路、運河、市場などのインフラの維持管理や、ゾーニング政策が、明確に住民の健康を守るために導入された[99]。中東のムフタスィブやイタリアの道路管理者などの役人は、罪、視覚的侵入、瘴気による汚染の複合的脅威と戦った[100][101][102][103]。技術ギルドは、廃棄物処理の重要な主体であり、メンバー間の正直さと労働安全を通じて、害の軽減を促進した。公共の医師を含む医療従事者は[104]、災害の予測と準備、道徳的な意味合いの強い病気とされたハンセン病患者と認識された人々の特定と隔離において、都市政府と協力した[105][106]。近隣地域でも、周辺のリスクのある場所を監視し、職人による汚染や動物の所有者の怠慢に対して適切な社会的・法的措置を講じることで、地域住民の健康を守るのに積極的だった。イスラム教とキリスト教の両方で、宗教機関、個人、慈善団体も、巡礼者のためにも、井戸、噴水、学校、橋などの都市の施設を寄贈することで、道徳的・身体的な幸福を促進した[107][108]。西ヨーロッパとビザンチンでは、コミュニティ全体のための予防措置と治療措置の両方として機能すると考えられていた宗教的な行列が一般的に行われていた[109]。

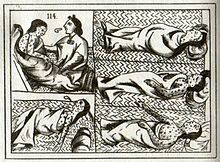

都市住民やその他のグループは、戦争、飢饉、洪水、広範な疾病などの災害に対応するための予防措置も講じた[110][111][112][113]。例えば、黒死病(1346年-53年)の最中とその後、東地中海と西ヨーロッパの住民は、大規模な人口減少に対して、一部は肉の消費や埋葬に関する既存の医学理論やプロトコルに基づいて、一部は新しいものを開発することで対応した[114][115][116]。後者には、検疫施設や衛生委員会の設置が含まれ、その一部は最終的に定期的な都市(後に国家)の機関になった[117][118]。その後の都市とその地域を守るための措置には、旅行者に健康パスポートを発行すること、地域住民を守るために警備員を配置して衛生的なコルドンを作ること、罹患率と死亡率の統計を収集することなどが含まれた[119][120][121]。このような措置は、人間や動物の病気に関するニュースが効率的に広まる、より良い交通・通信ネットワークに依存していた。

18世紀以降

産業革命の開始とともに、労働者階級の生活水準は、混雑した非衛生的な都市環境により悪化し始めた。19世紀の最初の40年間だけで、ロンドンの人口は倍増し、リーズやマンチェスターなどの新しい工業都市では、さらに大きな成長率が記録された。この急速な都市化は、救貧院や工場の周りに建設された大規模な連担都市における疾病の蔓延を悪化させた。これらの居住地は狭く原始的で、組織的な衛生設備がなかった。病気は避けられず、住民の劣悪な生活習慣によって、これらの地域での病気の潜伏が助長された。住宅不足により、スラムが急速に拡大し、一人当たりの死亡率は警戒すべきレベルまで上昇し、バーミンガムとリバプールではほぼ倍増した。トマス・マルサスは、1798年に人口過剰の危険性を警告した。彼の考えは、ジェレミー・ベンサムの考えとともに、19世紀初頭の政府の中で非常に影響力を持つようになった[122]。19世紀後半には、今後2世紀にわたる公衆衛生の改善の基本的なパターンが確立された。社会的弊害が特定され、民間の慈善家がそれに注意を向け、世論の変化が政府の行動につながったのである[122]。18世紀には、イングランドで自発的な病院が急速に増加した[123]。

予防接種の実践は、天然痘の治療におけるエドワード・ジェンナーの先駆的な業績に続いて、1800年代に始まった。ジェームズ・リンドによる船乗りの間での壊血病の原因の発見と、長距離航海での果物の導入による軽減は、1754年に発表され、この考えが王立海軍に採用されるきっかけとなった[124]。また、より広い公衆に健康問題を周知させる努力もなされた。1752年、イギリスの医師であるジョン・プリングル卿は、『Observations on the Diseases of the Army in Camp and Garrison』を発表し、軍隊の兵舎での適切な換気の重要性と、兵士のための便所の設置を提唱した[125]。

イングランドにおける公衆衛生法

衛生改革と公衆衛生制度の確立への最初の試みは、1840年代に行われた。ロンドン熱病院の医師、トマス・サウスウッド・スミスは、公衆衛生の重要性について論文を書き始め、1830年代に救貧法委員会の証言のために最初に呼ばれた医師の一人であり、ニール・アーノットやジェームズ・フィリップス・ケイとともに証言を行った[126]。スミスは、コレラや黄熱などの感染症の蔓延を制限するための検疫と衛生状態の改善の重要性について政府に助言した[127][128]。

救貧法委員会は、1838年の報告で、「予防措置の採用と維持に必要な支出は、最終的には現在常に発生している病気のコストよりも少なくなるだろう」と報告した。それは、疾病の伝播を可能にする条件を緩和するための大規模な政府の工学プロジェクトの実施を勧告した[122]。都市衛生協会は、1844年12月11日にロンドンのエクセター・ホールで結成され、イギリスにおける公衆衛生の発展を精力的に訴えた[129]。その結成は、エドウィン・チャドウィック卿が議長を務め、イギリスの都市における劣悪で非衛生的な状況に関する一連の報告書を作成した都市衛生委員会の1843年の設立に続くものであった[129]。

これらの国家的および地方的な運動は、1848年にようやく成立した1848年公衆衛生法につながった。この法律は、イングランドとウェールズの町や人口の多い場所の衛生状態を改善することを目的としており、中央機関として公衆衛生総局を置き、その下で単一の地方機関が水道、下水道、排水、清掃、舗装を管轄するようにした。この法律は、エドウィン・チャドウィックの働きかけに応じて、ジョン・ラッセル卿率いる自由党政権によって可決された。チャドウィックの画期的な報告書『労働者階級の衛生状態』は1842年に発表され[130]、その1年後に補足報告書が発表された[131]。この時期、ジェームズ・ニューランズは(リバプール特別区の都市衛生委員会が推進した1846年のリバプール衛生法の成立を受けて任命され)、リバプールで世界初の統合下水道システムを設計し(1848-1869年)、その後、ジョゼフ・バザルゲットがロンドンの下水道システムを作った(1858-1875年)。

1853年の種痘法は、イングランドとウェールズで天然痘の強制予防接種を導入した[132]。1871年までに、任命された予防接種担当官が運営する包括的な登録システムが法律で義務付けられた[133]。

その後の一連の公衆衛生法、特に1875年法によって、さらなる介入が行われた。改革には、下水道の建設、定期的なゴミ収集と焼却または埋立地での処分、清潔な水の供給、蚊の繁殖を防ぐための滞水の排水などが含まれた。

1889年感染症(届出)法は、感染症を地方衛生当局に報告することを義務付け、地方衛生当局は患者の病院への移送や家屋の消毒などの措置を講じることができるようになった[134]。

他国の公衆衛生法

アメリカ合衆国では、1866年にニューヨーク市で、州衛生局と地方衛生委員会をベースにした最初の公衆衛生機関が設立された[135]。

ワイマール共和国時代のドイツでは、国は多くの公衆衛生の大惨事に直面した[要実例]。ナチス党は、Volksgesundheit(ドイツ語で「国民の公衆衛生」の意味)によって医療を近代化することを目標としていた。この近代化は、成長分野である優生学と、個人の健康よりも集団の健康を優先する措置に基づいていた。第二次世界大戦の終結は、人体実験に関する一連の研究倫理であるニュルンベルク綱領につながった[136]。

日本では明治の文明開化以降の近代的な「公衆衛生」に相当する概念としては、当時医学の諸制度はドイツに倣っていたことが多かったため、独流のHygiene(衛生または衛生学)やイギリスの制度を模倣して導入されていった。1874年(明治7年)に医制が公布され各地方に医務取締を設置、その後1879年(明治12年)には中央衛生会(地方には衛生課)を設置、公選によって衛生委員が置かれる、といった民主的な体制を布いた。1892年(明治25年)7月にはペスト菌発見者のひとりとされる北里柴三郎が中央衛生会委員として専任される。1893年(明治26年)には、これらの機能を警察部に移管、上意下達式にとなる。これは、中央集権型政治体制に移行してきたこととともに、当時の急速な感染症拡大へ対応を素早くとりたい意図もあった。1937年(昭和12年)には保健所法が公布された。

柳沢[137]によれば、後述する国立公衆衛生院院長の古屋は、公衆衛生の定義を次のように述べている。「公衆衛生とは、公衆団体の責任に於いて、われらの生命と健康とを脅かす社会的並びに医学的原因の除き、かつわれらの精神的及び肉体的能力の向上をはかる学問及び技術である」戦後は、日本国憲法に基づいて1947年に保健所法が大幅に改正され保健所政令市制度が導入された。現在は地域保健法となっている。

疫学

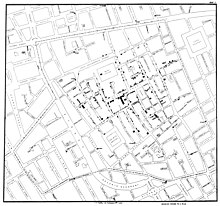

疫学の科学は、ロンドンでの1854年のコレラの流行の原因として汚染された公共の井戸を特定したジョン・スノウによって確立された。スノウは、当時支配的だった瘴気説ではなく、細菌説を信じていた。地元住民に話を聞くことで(ヘンリー・ホワイトヘッド師の助けを借りて)、彼は流行の原因がブロード・ストリート(現在のブロードウィック・ストリート)にある公共の水汲み場であることを突き止めた。スノウによるブロード・ストリートの水汲み場の水サンプルの化学的・顕微鏡的検査では、その危険性を決定的に証明できなかったが、彼の病気のパターンに関する研究は十分に説得力があり、地方議会に井戸のハンドルを取り外して閉鎖するよう説得するのに十分であった[138]。

スノウはその後、コレラ症例がポンプの周りに集中していることを示すためにドットマップを使用した。また、水源の質とコレラ症例の関連を示すために統計を用いた。彼は、サウスワークおよびヴォクスホール水道会社がテムズ川の汚水に汚染された区間から水を取水し、家庭に供給していたため、コレラの発生率が上昇していることを示した。スノウの研究は、公衆衛生と地理学の歴史における主要な出来事であった。それは、疫学の科学の創始的事件と見なされている[139][140]。

感染症の制御

フランスの化学者ルイ・パスツールとドイツの科学者ロベルト・コッホによる細菌学の先駆的な業績により、20世紀の変わり目に、特定の疾病の原因となる細菌を分離し、ワクチンを開発する方法が開発された。イギリスの医師ロナルド・ロスは、蚊がマラリアを媒介することを突き止め、この病気に対処するための基礎を築いた[141]。ジョゼフ・リスターは、感染を排除するために消毒剤を使用した手術を導入し、外科に革命をもたらした。フランスの疫学者ポール・ルイ・シモンは、ペストがネズミの背中のノミによって運ばれることを証明し[142]、キューバの科学者カルロス・J・フィンレーと米国のウォルター・リードとジェームズ・キャロルは、蚊が黄熱の原因となるウイルスを運ぶことを証明した[143][144]。ブラジルの科学者カルロス・シャガスは、ある熱帯病とそのベクターを特定した[145]。

現代

公衆衛生に関する出来事で以下のようなものがあった。

- BSE(Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy)牛海綿状脳症又は伝達性海綿状脳症。

- 重症急性呼吸器症候群(SARS、Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome)サーズと発音する。新型肺炎。

- トリインフルエンザ(高病原性トリインフルエンザ、旧称家禽ペスト、Orthomyxoviridae Influenza virus A)

- 2004年2~3月猛威をふるう。

- 関係府県の情報は、二転三転した。正確な情報を消費者に伝えることができなかった。

- 関係府県の情報の発表が後手後手に回った。BSEの反省を全く生かせていなかった。

- アスベスト問題(石綿問題)

- たばこ規制枠組条約(2005年2月27日締結の多数国間条約。世界初の公衆衛生分野における条約[146]

- 健康増進法の制定(2002年8月2日)

- 2009年新型インフルエンザ(豚由来インフルエンザ、Pandemic 2009H1N1)

- 2009年1月~2010年3月猛威をふるう。

- 新型コロナウイルス感染症 (2019年)

- ^ a b Gatseva, Penka D.; Argirova, Mariana (1 June 2011). “Public health: the science of promoting health” (英語). Journal of Public Health 19 (3): 205–206. doi:10.1007/s10389-011-0412-8. ISSN 1613-2238.

- ^ Winslow, Charles-Edward Amory (1920). “The Untilled Field of Public Health”. Modern Medicine 2 (1306): 183–191. Bibcode: 1920Sci....51...23W. doi:10.1126/science.51.1306.23. PMID 17838891.

- ^ a b “What is Public Health”. Centers for Disease Control Foundation. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control. 2017年1月27日閲覧。

- ^ What is the WHO definition of health? from the Preamble to the Constitution of WHO as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19 June – 22 July 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States (Official Records of WHO, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948. The definition has not been amended since 1948.

- ^ PERDIGUERO, E. (2001-07-01). “Anthropology in public health. Bridging differences in culture and society.”. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 55 (7): 528b–528. doi:10.1136/jech.55.7.528b. ISSN 0143-005X. PMC 1731924.

- ^ Lincoln C Chen; David Evans; Tim Evans; Ritu Sadana; Barbara Stilwell; Phylida Travis; Wim Van Lerberghe; Pascal Zurn (2006). World Health Report 2006: working together for health. Geneva: WHO. OCLC 71199185

- ^ Jamison, D T; Mosley, W H (January 1991). “Disease control priorities in developing countries: health policy responses to epidemiological change.”. American Journal of Public Health 81 (1): 15–22. doi:10.2105/ajph.81.1.15. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 1404931. PMID 1983911.

- ^ Rosen, George (2015). A history of public health (Revised expanded). Baltimore. ISBN 978-1-4214-1601-4. OCLC 878915301

- ^ Porter, Dorothy (1999). Health, Civilization and the State: A History of Public Health from Ancient to Modern Times. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415200363

- ^ a b c d e Crook, Tom (2016). Governing systems: modernity and the making of public health in England, 1830–1910. Oakland, California. ISBN 978-0-520-96454-9. OCLC 930786561

- ^ “The World Health Organization and the transition from "international" to "global" public health”. Am J Public Health 96 (1): 62–72. (January 2006). doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.050831. PMC 1470434. PMID 16322464.

- ^ “Towards a common definition of global health”. Lancet 373 (9679): 1993–5. (June 2009). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9. PMC 9905260. PMID 19493564.

- ^ “The World Health Organization and the transition from "international" to "global" public health”. Am J Public Health 96 (1): 62–72. (January 2006). doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.050831. PMC 1470434. PMID 16322464.

- ^ a b “Towards a common definition of global health”. Lancet 373 (9679): 1993–5. (June 2009). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9. PMC 9905260. PMID 19493564.

- ^ a b c d e Jung, Paul; Lushniak, Boris D. (March 2017). “Preventive Medicine's Identity Crisis” (英語). American Journal of Preventive Medicine 52 (3): e85–e89. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.037. PMID 28012813.

- ^ a b c Valles, Sean A. (2018). Philosophy of population health : philosophy for a new public health era. London. ISBN 978-1-351-67078-4. OCLC 1035763221

- ^ a b Crook, Tom (2016). Governing systems: modernity and the making of public health in England, 1830–1910. Oakland, California. ISBN 978-0-520-96454-9. OCLC 930786561

- ^ Joint Task Group on Public Health Human Resources; Advisory Committee on Health Delivery & Human Resources; Advisory Committee on Population Health & Health Security (2005). Building the public health workforce for the 21st century. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada. OCLC 144167975

- ^ Joint Task Group on Public Health Human Resources; Advisory Committee on Health Delivery & Human Resources; Advisory Committee on Population Health & Health Security (2005). Building the public health workforce for the 21st century. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada. OCLC 144167975

- ^ Global Public-Private Partnership for Handwashing with Soap. Handwashing research Archived 16 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine., accessed 19 April 2011.

- ^ Wang, Fahui (2020-01-02). “Why public health needs GIS: a methodological overview” (英語). Annals of GIS 26 (1): 1–12. Bibcode: 2020AnGIS..26....1W. doi:10.1080/19475683.2019.1702099. ISSN 1947-5683. PMC 7297184. PMID 32547679.

- ^ a b c d e f g Holland, Stephen (2015). Public health ethics (Second ed.). Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-7456-6218-3. OCLC 871536632

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Michael (2002-01-04) (英語). The Tyranny of Health: Doctors and the Regulation of Lifestyle. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-56346-3

- ^ a b Fiona, Sim; Martin, McKee (2011-09-01) (英語). Issues In Public Health. McGraw-Hill Education (UK). ISBN 978-0-335-24422-5

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Katie; Tinning, Richard (2014-02-05) (英語). Health Education: Critical perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-07214-8

- ^ Zembylas, Michalinos (2021-05-06) (英語). Affect and the Rise of Right-Wing Populism: Pedagogies for the Renewal of Democratic Education. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-83840-5

- ^ “The declines in infant mortality and fertility: Evidence from British cities in demographic transition”. 2012年12月17日閲覧。

- ^ “10 facts on breastfeeding”. World Health Organization. 2011年4月20日閲覧。

- ^ World Health Organization. Diabetes Fact Sheet N°312, January 2011. Accessed 19 April 2011.

- ^ The Lancet (2010). “Type 2 diabetes—time to change our approach”. The Lancet 375 (9733): 2193. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61011-2. PMID 20609952.

- ^ World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight Fact sheet N°311, Updated June 2016. Accessed 19 April 2011.

- ^ “How can local authorities reduce obesity? Insights from NIHR research”. NIHR Evidence. (19 May 2022).

- ^ Flynn, Michael A. (2018-11-19). “Im/migration, Work, and Health: Anthropology and the Occupational Health of Labor Im/migrants”. Anthropology of Work Review: AWR 39 (2): 116–123. doi:10.1111/awr.12151. ISSN 0883-024X. PMC 6503519. PMID 31080311.

- ^ Victora, Cesar G; Vaughan, J Patrick; Barros, Fernando C; Silva, Anamaria C; Tomasi, Elaine (2000). “Explaining trends in inequities: evidence from Brazilian child health studies”. The Lancet 356 (9235): 1093–1098. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02741-0. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 11009159.

- ^ coaccess. doi:10.51952/9781847423221.ch005 2023年6月6日閲覧。.

- ^ Flynn, Michael A.; Check, Pietra; Steege, Andrea L.; Sivén, Jacqueline M.; Syron, Laura N. (2021-12-29). “Health Equity and a Paradigm Shift in Occupational Safety and Health”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (1): 349. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010349. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 8744812. PMID 35010608.

- ^ “The U.S. Government and the World Health Organization” (英語). The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (2019年1月24日). 2020年3月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年3月18日閲覧。

- ^ “WHO Constitution, BASIC DOCUMENTS, Forty-ninth edition”. 2020年4月1日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2024年3月10日閲覧。

- ^ “What we do” (英語). www.who.int. 2020年3月17日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年3月17日閲覧。

- ^ Alkhuli, Muhammad Ali (英語). English for Nursing and Medicine. دار الفلاح للنشر والتوزيع. ISBN 978-9957-552-36-7

- ^ "Public health principles and neurological disorders". Neurological Disorders: Public Health Challenges (Report). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2006.

- ^ “Collaboration between local health and local government agencies for health improvement”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012 (10): CD007825. (17 October 2012). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007825.pub6. PMC 9936257. PMID 23076937.

- ^ a b c Butcher, Lola (17 November 2020). “Pandemic puts all eyes on public health”. Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-111720-1 2022年3月2日閲覧。.

- ^ World Health Organization. The role of WHO in public health, accessed 19 April 2011.

- ^ World Health Organization. Public health surveillance, accessed 19 April 2011.

- ^ Botchway, Stella; Hoang, Uy (2016). “Reflections on the United Kingdom's first public health film festival”. Perspectives in Public Health 136 (1): 23–24. doi:10.1177/1757913915619120. PMID 26702114.

- ^ Valerie Curtis and Robert Aunger. "Motivational mismatch: evolved motives as the source of—and solution to—global public health problems". In Roberts, S. C. (2011). Roberts, S. Craig. ed. Applied Evolutionary Psychology. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199586073.001.0001. ISBN 9780199586073

- ^ Gillam Stephen; Yates, Jan; Badrinath, Padmanabhan (2007). Essential Public Health: theory and practice. Cambridge University Press. OCLC 144228591

- ^ Pencheon, David; Guest, Charles; Melzer, David; Gray, JA Muir (2006). Pencheon, David. ed. Oxford Handbook of Public Health Practice. Oxford University Press. OCLC 663666786

- ^ Smith, Sarah; Sinclair, Don; Raine, Rosalind; Reeves, Barnarby (2005). Health Care Evaluation. Understanding Public Health. Open University Press. OCLC 228171855

- ^ Sanderson, Colin J.; Gruen, Reinhold (2006). Analytical Models for Decision Making. Understanding Public Health. Open University Press. OCLC 182531015

- ^ Byrd, Nick; Białek, Michał (2021). “Your Health vs. My Liberty: Philosophical beliefs dominated reflection and identifiable victim effects when predicting public health recommendation compliance during the COVID-19 pandemic” (英語). Cognition 212: 104649. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2021.104649. PMC 8599940. PMID 33756152.

- ^ United Nations. Press Conference on General Assembly Decision to Convene Summit in September 2011 on Non-Communicable Diseases. New York, 13 May 2010.

- ^ Lincoln C Chen; David Evans; Tim Evans; Ritu Sadana; Barbara Stilwell; Phylida Travis; Wim Van Lerberghe; Pascal Zurn (2006). World Health Report 2006: working together for health. Geneva: WHO. OCLC 71199185

- ^ a b Jamison, D T; Mosley, W H (January 1991). “Disease control priorities in developing countries: health policy responses to epidemiological change.”. American Journal of Public Health 81 (1): 15–22. doi:10.2105/ajph.81.1.15. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 1404931. PMID 1983911.

- ^ “Malaria – Malaria Worldwide – Impact of Malaria” (英語). CDC (2021年1月26日). 2021年10月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Fact sheet about Malaria” (英語). www.who.int. 2021年10月19日閲覧。

- ^ “10 facts on breastfeeding”. World Health Organization. 2011年4月20日閲覧。

- ^ Organization, World Health (2010). Equity, Social Determinants and Public Health Programmes. World Health Organization. ISBN 9789241563970

- ^ Richard G. Wilkinson; Michael G. Marmot, eds (2003). The Solid Facts: Social Determinants of Health. WHO. OCLC 54966941

- ^ Bank, European Investment (2023年2月2日). “Health Overview 2023” (英語). 2024年3月10日閲覧。

- ^ Leider, Jonathon P.; Yeager, Valerie A.; Kirkland, Chelsey; Krasna, Heather; Hare Bork, Rachel; Resnick, Beth (1 April 2023). “The State of the US Public Health Workforce: Ongoing Challenges and Future Directions” (英語). Annual Review of Public Health 44 (1): annurev–publhealth–071421-032830. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-071421-032830. ISSN 0163-7525. PMID 36692395 2023年3月14日閲覧。.

- ^ Robert Huish and John M. Kirk (2007), "Cuban Medical Internationalism and the Development of the Latin American School of Medicine", Latin American Perspectives, 34; 77

- ^ a b c d Bendavid, Eran; Bhattacharya, Jay (2014). “The Relationship of Health Aid to Population Health Improvements”. JAMA Internal Medicine 174 (6): 881–887. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.292. PMC 4777302. PMID 24756557.

- ^ Twumasi, Patrick (1 April 1981). “Colonialism and international health: A study in social change in Ghana”. Social Science & Medicine. Part B: Medical Anthropology 15 (2): 147–151. doi:10.1016/0160-7987(81)90037-5. ISSN 0160-7987. PMID 7244686.

- ^ a b c Afridi, Muhammad Asim; Ventelou, Bruno (1 March 2013). “Impact of health aid in developing countries: The public vs. the private channels”. Economic Modelling 31: 759–765. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2013.01.009. ISSN 0264-9993.

- ^ “TDR | World Health Organization”. 2024年3月10日閲覧。

- ^ a b Shwank, Oliver. “Global Health Initiatives and Aid Effectiveness in the Health Sector”. 2024年3月10日閲覧。

- ^ Afridi, Muhammad Asim; Ventelou, Bruno (1 March 2013). “Impact of health aid in developing countries: The public vs. the private channels”. Economic Modelling 31: 759–765. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2013.01.009. ISSN 0264-9993.

- ^ a b Bendavid, Eran; Bhattacharya, Jay (2014). “The Relationship of Health Aid to Population Health Improvements”. JAMA Internal Medicine 174 (6): 881–887. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.292. PMC 4777302. PMID 24756557.

- ^ “2015 – United Nations sustainable development agenda”. United Nations Sustainable Development. 2015年11月25日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Sustainable development goals – United Nations”. United Nations Sustainable Development. 2015年11月25日閲覧。

- ^ “Health – United Nations Sustainable Development”. United Nations Sustainable Development. 2015年11月25日閲覧。

- ^ World Development Report 2015年11月25日閲覧。.

- ^ Rosen, George (2015). A history of public health (Revised expanded). Baltimore. ISBN 978-1-4214-1601-4. OCLC 878915301

- ^ Porter, Dorothy (1999). Health, Civilization and the State: A History of Public Health from Ancient to Modern Times. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415200363

- ^ Cosmacini, Giorgio (2005). Storia della medicina e della sanità in Italia: dalla peste nera ai giorni nostri. Bari: Laterza

- ^ Shephard, Roy J. (2015). An illustrated history of health and fitness, from pre-history to our post-modern world. Cham: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-11671-6. OCLC 897376985

- ^ Berridge, V; (2016) Public Health: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN 9780199688463

- ^ Chattopadhyay, Aparna (1968). “Hygienic Principles in the Regulations of Food Habits in the Dharma Sūtras”. Nagarjun 11: 194–99.

- ^ Leung, Angela Ki Che. "Hygiène et santé publique dans la Chine pré-moderne". In Les hygienists. Enjeux, modèles et practiques. Edited by Patrice Bourdelais, 343–71 (Paris: Belin, 2001)

- ^ Harvey, Herbert R. (1981). “Public Health in Aztec Society”. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 57 (2): 157–65. PMC 1805201. PMID 7011458.

- ^ Gunyah, Goondie + Wurley: the Aboriginal architecture of Australia. (2008-09-01)

- ^ Gammage, Bill. (2014). Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia.. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74269-352-1. OCLC 956710111

- ^ Stearns, Justin K. (2011). Infectious ideas: contagion in premodern Islamic and Christian thought in the Western Mediterranean. Johns Hopkins Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9873-0. OCLC 729944227

- ^ Rawcliffe, Carole. (2019). Urban Bodies - Communal Health in Late Medieval English Towns and Cities.. Boydell & Brewer, Limited. ISBN 978-1-78327-381-2. OCLC 1121393294

- ^ Geltner, G. (2019). Roads to Health: Infrastructure and Urban Wellbeing in Later Medieval Italy. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-5135-7. OCLC 1076422219

- ^ Varlik, Nükhet (2015-07-22). Plague and Empire in the Early Modern Mediterranean World. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139004046. ISBN 978-1-139-00404-6

- ^ McVaugh, Michael R. "Arnald of Villanova's Regimen Almarie (Regimen Castra Sequentium) and Medieval Military Medicine". Viator 23 (1992): 201–14

- ^ Nicoud, Marilyn. (2013). Les régimes de santé au Moyen Âge Naissance et diffusion d'une écriture médicale en Italie et en France (XIIIe- XVe siècle). Publications de l'École française de Rome. ISBN 978-2-7283-1006-7. OCLC 960812022

- ^ Ibn Riḍwān, ʻAlī Abū al-Ḥasan al-Miṣrī (1984). Gamal, Adil S.. ed. Medieval Islamic medicine: Ibn Riḍwān's treatise "On the prevention of bodily ills in Egypt.. University of California Press. OCLC 469624320

- ^ L.J. Rather, 'The Six Things Non-Natural: A Note on the Origins and Fate of a Doctrine and a Phrase', Clio Medica, iii (1968)

- ^ Luis García-Ballester, 'On the Origins of the Six Non-Natural Things in Galen', in Jutta Kollesch and Diethard Nickel (eds.), Galen und das hellenistische Erbe: Verhandlungen des IV. Internationalen Galen-Symposiums veranstaltet vom Institut für Geschichte der Medizin am Bereich Medizin (Charité) der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin 18.-20. September 1989 (Stuttgart, 1993)

- ^ Janna Coomans and G. Geltner, 'On the Street and in the Bath-House: Medieval Galenism in Action?' Anuario de Estudios Medievales, xliii (2013)

- ^ Israelovich, Ido. "Medical Care in the Roman Army during the High Empire". In Popular Medicine in Graeco-Roman Antiquity: Explorations. Edited by William V. Harris, 126–46 (Leiden: Brill, 2016)

- ^ Geltner, G. (January 2019). “In the Camp and on the March: Military Manuals as Sources for Studying Premodern Public Health” (英語). Medical History 63 (1): 44–60. doi:10.1017/mdh.2018.62. ISSN 0025-7273. PMC 8670759. PMID 30556517.

- ^ Harvey, Barbara F. (2002). Living and dying in England, 1100–1540: the monastic experience. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-820431-0. OCLC 612358999

- ^ Agostino Paravicini Bagliani, 'La Mobilità della Curia romana nel Secolo XIII: Riflessi locali', in Società e Istituzioni dell'Italia comunale: l'Esempio di Perugia (Secoli XII-XIV), 2 vols. (Perugia, 1988)

- ^ Coomans, Janna (February 2019). “The king of dirt: public health and sanitation in late medieval Ghent” (英語). Urban History 46 (1): 82–105. doi:10.1017/S096392681800024X. ISSN 0963-9268.

- ^ Glick, T.F. "New Perspectives on the Hisba and its Hispanic Derivatives". Al-Qantara 13 (1992): 475–89

- ^ Kinzelbach, Annemarie. "Infection, Contagion, and Public Health in Late Medieval German Imperial Towns". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 61 (2006): 369–89

- ^ Jørgensen, Dolly. "Cooperative Sanitation: Managing Streets and Gutters in Late Medieval England and Scandinavia". Technology and Culture 49 (2008): 547–67

- ^ Henderson, John. "Public Health, Pollution and the Problem of Waste Disposal in Early Modern Tuscany". In Le interazioni fra economia e ambiente biologico nell'Europa preindustriale. Secc. XIII-XVIII. Edited by Simonetta Cavaciocchi, 373–82 (Florence: Firenze University Press, 2010)

- ^ Nutton, Vivian. "Continuity or Rediscovery? The City Physician in Classical Antiquity and Mediaeval Italy". In The Town and State Physician in Europe. Edited by Andrew W. Russell, 9–46. (Wolfenbüttel: Herzog August Bibliothek, 1981)

- ^ Rawcliffe, Carole. (2009). Leprosy in medieval England. The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-454-0. OCLC 884314023

- ^ Demaitre, Luke E. (2007). Leprosy in premodern medicine: a malady of the whole body. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8613-3. OCLC 799983230

- ^ Adam Sabra. (2006). Poverty and charity in medieval islam: mamluk egypt, 1250–1517.. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-03474-4. OCLC 712129032

- ^ Cascoigne, Alison L. "The Water Supply of Tinnīs: Public Amenities and Private Investments". In Cities in the Pre-Modern Islamic World: The Urban Impact of Religion, State and Society. Edited by Amira K. Bennison and Alison L. Gascoigne, 161-76 (London: Routledge, 2007)

- ^ Horden, Peregrine. "Ritual and Public Health in the Early Medieval City". In Body and City: Histories of Urban Public Health. Edited by Sally Sheard and Helen Power, 17–40 (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2000)

- ^ Falcón, Isabel. "Aprovisionamiento y sanidad en Zaragoza en el siglo XV". Acta Historica et Archaeologica Mediaeval 19 (1998): 127–44

- ^ Duccio Balestracci, 'The Regulation of Public Health in Italian Medieval Towns', in Helmut Hundsbichler, Gerhard Jaritz and Thomas Kühtreiber (eds.), Die Vielfalt der Dinge: Neue Wege zur Analyse mittelaltericher Sachkultur (Vienna, 1998)

- ^ Ewert, Ulf Christian. "Water, Public Hygiene and Fire Control in Medieval Towns: Facing Collective Goods Problems while Ensuring the Quality of Life". Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung 32 (2007): 222–52

- ^ Anja Petaros et al., 'Public Health Problems in the Medieval Statutes of Croatian Adriatic Coastal Towns: From Public Morality to Public Health', Journal of Religion and Health, lii (2013)

- ^ Skelton, Leona J. (2016). Sanitation in urban Britain, 1560–1700. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-21789-3. OCLC 933433427

- ^ Carmichael, Ann G. "Plague Legislation in the Italian Renaissance". Bulletin of the History of Medicine 7 (1983): 508–25

- ^ Geltner, G. (2019). “The Path to Pistoia: Urban Hygiene Before the Black Death” (英語). Past & Present 246: 3–33. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtz028. hdl:11245.1/3cff1e5a-78b1-4f40-a754-a28ffbb456cf.

- ^ Blažina-Tomić, Zlata; Blažina, Vesna (2015). Expelling the plague: the health office and the implementation of quarantine in Dubrovnik, 1377–1533. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-4539-7. OCLC 937888436

- ^ Gall, Gabriella Eva Cristina, Stephan Lautenschlager and Homayoun C. Bagheri. "Quarantine as a Public Health Measure against an Emerging Infectious Disease: Syphilis in Zurich at the Dawn of the Modern Era (1496–1585)". Hygiene and Infection Control 11 (2016): 1–10

- ^ Cipolla, Carlo M. (1973). Cristofano and the plague: a study in the history of public health in the age of Galileo. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02341-2. OCLC 802505260

- ^ Carmichael, Ann G. (2014). Plague and the poor in Renaissance Florence. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-63436-7. OCLC 906714501

- ^ Cohn, Samuel K. (2012). Cultures of plague: medical thinking at the end of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957402-5. OCLC 825731416

- ^ a b c “Public Health”. Encyclopædia Britannica (2019年5月20日). 2024年3月10日閲覧。

- ^ Carruthers, G. Barry; Carruthers, Lesley A. (2005). A History of Britain's Hospitals. Book Guild Publishers. ISBN 9781857769050

- ^ Vale, Brian. "The Conquest of Scurvy in the Royal Navy 1793–1800: A Challenge to Current Orthodoxy". The Mariners' Mirror, volume 94, number 2, May 2008, pp. 160–175.

- ^ Selwyn, S (1966), “Sir John Pringle: hospital reformer, moral philosopher and pioneer of antiseptics”, Medical History 10 (3): 266–74, July 1966, doi:10.1017/s0025727300011133, PMC 1033606, PMID 5330009

- ^ Amanda J. Thomas (2010). The Lambeth cholera outbreak of 1848–1849: the setting, causes, course and aftermath of an epidemic in London. McFarland. pp. 55–6. ISBN 978-0-7864-3989-8

- ^ Margaret Stacey (1 June 2004). The Sociology of Health and Healing. Taylor and Francis. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-203-38004-8

- ^ Samuel Edward Finer (1952). The Life and Times of Sir Edwin Chadwick. Methuen. pp. 424–5. ISBN 978-0-416-17350-5

- ^ a b Ashton, John; Ubido, Janet (1991). “The Healthy City and the Ecological Idea”. Journal of the Society for the Social History of Medicine 4 (1): 173–181. doi:10.1093/shm/4.1.173. PMID 11622856. オリジナルの24 December 2013時点におけるアーカイブ。 2013年7月8日閲覧。.

- ^ Chadwick, Edwin (1842). “Chadwick's Report on Sanitary Conditions”. excerpt from Report...from the Poor Law Commissioners on an Inquiry into the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain (pp. 369–372) (online source). added by Laura Del Col: to The Victorian Web 2009年11月8日閲覧。

- ^ Chadwick, Edwin (1843). Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain. A Supplementary Report on the results of a Special Inquiry into The Practice of Interment in Towns. London: Printed by R. Clowes & Sons, for Her Majesty's Stationery Office Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org)

- ^ Brunton, Deborah (2008). The Politics of Vaccination: Practice and Policy in England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland, 1800–1874. University Rochester Press. pp. 39. ISBN 9781580460361

- ^ “Decline of Infant Mortality in England and Wales, 1871–1948: a Medical Conundrum”. 2012年12月17日閲覧。

- ^ Mooney, Graham (2015). Intrusive Interventions: Public Health, Domestic Space, and Infectious Disease Surveillance in England, 1840–1914. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 9781580465274

- ^ United States Public Health Service, Municipal Health Department Practice for the Year 1923 (Public Health Bulletin # 164, July 1926), pp. 348, 357, 364

- ^ Bachrach, Susan (July 29, 2004). “In the Name of Public Health — Nazi Racial Hygiene”. The New England Journal of Medicine 351 (5): 417–420. doi:10.1056/NEJMp048136. PMID 15282346. オリジナルのJan 14, 2024時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ 柳沢文徳「食品衛生」共立出版、1952年6月、p.1

- ^ Vinten-Johansen, Peter, et al. (2003). Cholera, Chloroform, and the Science of Medicine: A Life of John Snow. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513544-X

- ^ ジョンソン、スティーブン (2006). ゴーストマップ: ロンドンで最も恐ろしい流行病の物語-そしてそれがいかに科学、都市、現代世界を変えたか. リバーヘッド・ブックス. ISBN 1-59448-925-4

- ^ Miquel Porta (2014). A Dictionary of Epidemiology (6th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-997673-7

- ^ “:: Laboc Hospital – A Noble Prize Winner's Workplace”. easternpanorama.in. 2013年11月5日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2013年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ Edward Marriott (1966) in "Plague. A Story of Science, Rivalry and the Scourge That Won't Go Away" ISBN 978-1-4223-5652-4

- ^ Ronn F. Pineo, "Public Health" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 4, p. 481. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ^ Pierce J.R., J, Writer. 2005. Yellow Jack: How Yellow Fever Ravaged America and Walter Reed Discovered its Deadly Secrets. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-47261-1

- ^ Pineo, "Public Health", p. 481.

- ^ たばこと健康に関する情報ページ(厚生労働省健康局総務課生活習慣病対策室健康情報管理係)

- ^ a b c "Achievements in Public Health, 1900–1999" (PDF). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 48, no. 50. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 24 December 1999.

- ^ Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Public Health Workforce Core Competencies, accessed 19 April 2011.

- ^ White, Franklin (2013). “The Imperative of Public Health Education: A Global Perspective”. Medical Principles and Practice 22 (6): 515–529. doi:10.1159/000354198. PMC 5586806. PMID 23969636.

- ^ 社会健康医学系専攻の目指すもの - 京都大学大学院医学研究科社会健康医学系専攻

- ^ Welch, William H.; Rose, Wickliffe (1915). Institute of Hygiene: Being a report by Dr. William H. Welch and Wickliffe Rose to the General Education Board, Rockefeller Foundation (Report). pp. 660–668. reprinted in Fee, Elizabeth (1992). The Welch-Rose Report: Blueprint for Public Health Education in America. Washington, DC: Delta Omega Honorary Public Health Society. オリジナルの7 May 2012時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b c d Patel, Kant; Rushefsky, Mark E.; McFarlane, Deborah R. (2005). The Politics of Public Health in the United States. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 91. ISBN 978-0-7656-1135-2

- ^ “Antagonism and accommodation: interpreting the relationship between public health and medicine in the United States during the 20th century”. American Journal of Public Health 90 (5): 707–15. (2000). doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.5.707. PMC 1446218. PMID 10800418.

- ^ White, Kerr L. (1991). Healing the schism: Epidemiology, medicine, and the public's health. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-97574-0

- ^ Darnell, Regna (2008). Histories of anthropology annual. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 36. ISBN 978-0-8032-6664-3

- ^ Dyer, John Percy (1966). Tulane: the biography of a university, 1834-1965. Harper & Row. pp. 136

- ^ Burrow, Gerard N. (2002). A history of Yale's School of Medicine: passing torches to others. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300132885. OCLC 182530966

- ^ Education of the Physician: International Dimensions. Education Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates., Association of American Medical Colleges. Meeting. (1984 : Chicago, Ill), p. v.

- ^ Milton Terris, "The Profession of Public Health", Conference on Education, Training, and the Future of Public Health. 22–24 March 1987. Board on Health Care Services. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, p. 53.

- ^ Sheps, Cecil G. (1973). “Schools of Public Health in Transition”. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. Health and Society 51 (4): 462–468. doi:10.2307/3349628. JSTOR 3349628.

- ^ Kar, Snehendu B. (2018-05-18) (英語). Empowerment of Women for Promoting Health and Quality of Life. Oxford University Press. pp. 69. ISBN 978-0-19-938467-9

- ^ “Schools of Public Health and Public Health Programs”. 公衆衛生教育協議会 (2011年3月11日). 2012年6月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2011年3月30日閲覧。

- ^ Berke, Olaf; Sobkowich, Kurtis; Bernardo, Theresa M. (2020-11-01). “Celebration day: 400th birthday of John Graunt, citizen scientist of London”. Environmental Health Review 63 (3): 67–69. doi:10.5864/d2020-018. ISSN 0319-6771.

- ^ Winkelstein, Warren (July 2008). “Lemuel Shattuck: Architect of American Public Health” (英語). Epidemiology 19 (4): 634. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31817307f2. ISSN 1044-3983. PMID 18552594.

- ^ The Commonwealth Fund (1936). “Snow on cholera: A reprint of two paper: John Snow, M.D”. The Health Officer 1 (8): 306.

- ^ Halliday, Stephen (2013). The Great Stink of London: Sir Joseph Bazalgette and the Cleansing of the Victorian Metropolis. The History Press. ISBN 978-0752493787

- ^ “A Theory of Germs”. Science, Medicine, and Animals. National Academies Press (US). (4 January 2024)

- ^ Lakhtakia, Ritu (2014). “The Legacy of Robert Koch: Surmise, search, substantiate”. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal 14 (1): e37–41. doi:10.12816/0003334. PMC 3916274. PMID 24516751.

- ^ https://history.info/on-this-day/1843-robert-koch-man-saved-millions-lives/

- ^ Beitsch, Leslie M.; Yeager, Valerie A.; Moran, John (18 March 2015). “Deciphering the Imperative: Translating Public Health Quality Improvement into Organizational Performance Management Gains”. Annual Review of Public Health 36 (1): 273–287. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122810. PMID 25494050.

- ^ Parry, Manon S. (April 2006). “Sara Josephine Baker (1873–1945)”. American Journal of Public Health 96 (4): 620–621. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.079145. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 1470556.

- ^ Mackie, Elizabeth M; Scott Wilson, T. (12 November 1994). “Obituary N.I.Wattie”. British Medical Journal 309: 1297.

- ^ Asimov, Nanette (2005年9月1日). “Ruth Huenemann – pioneer in study of childhood obesity”. SF Gate. Hearts Newspapers 2022年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Mangalurean doctor's pilot project helps bring down malnutrition in Yelburga”. The Times of India. (2023年8月27日). ISSN 0971-8257 2023年9月23日閲覧。

- ^ “Canada: International Health Care System Profiles”. international.commonwealthfund.org. 2020年5月25日閲覧。

- ^ Pineo, "Public Health", p. 483.

- ^ Hanni Jalil, "Curing a Sick Nation: Public Health and Citizenship in Colombia, 1930–1940". PhD dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara 2015.

- ^ Nicole Pacino, "Prescription for a Nation: Public Health in Post-Revolutionary Bolivia, 1952–1964". PhD dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara 2013.

- ^ “Ghana”. CDC Global Health. 2018年4月9日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Agyepong, Irene Akua; Manderson, Lenore (January 1999). “Mosquito Avoidance and Bed Net Use in the Greater Accra Region, Ghana”. Journal of Biosocial Science 31 (1): 79–92. doi:10.1017/S0021932099000796. ISSN 1469-7599. PMID 10081239.

- ^ “Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2014”. 2020年5月18日閲覧。

- ^ Leider, Jonathon P.; Resnick, Beth; Bishai, David; Scutchfield, F. Douglas (1 April 2018). “How Much Do We Spend? Creating Historical Estimates of Public Health Expenditures in the United States at the Federal, State, and Local Levels”. Annual Review of Public Health 39 (1): 471–487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013455. ISSN 0163-7525. PMID 29346058.

- ^ a b Himmelstein, David U.; Woolhandler, Steffie (January 2016). “Public Health's Falling Share of US Health Spending”. American Journal of Public Health 106 (1): 56–57. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302908. PMC 4695931. PMID 26562115.

- ^ Alfonso, Y. Natalia; Leider, Jonathon P.; Resnick, Beth; McCullough, J. Mac; Bishai, David (1 April 2021). “US Public Health Neglected: Flat Or Declining Spending Left States Ill Equipped To Respond To COVID-19”. Health Affairs 40 (4): 664–671. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01084. ISSN 0278-2715. PMC 9890672. PMID 33764801.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (2012) (英語). For the Public's Health: Investing in a Healthier Future. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. p. 2. doi:10.17226/13268. ISBN 978-0-309-22107-8. PMID 24830052

- ^ “Health Care Costs Accounted for 17.7 Percent of GDP in 2018”. California Health Care Foundation (2020年6月2日). 2022年3月2日閲覧。

- ^ “A dozen facts about the economics of the US health-care system”. Brookings Institution (2020年3月10日). 2022年3月2日閲覧。

- ^ Wallace, Megan; Sharfstein, Joshua M. (6 January 2022). “The Patchwork U.S. Public Health System”. New England Journal of Medicine 386 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2104881. PMID 34979071.

- ^ “Explore Public Health Funding in the United States | 2021 Annual Report” (英語). America's Health Rankings. 2022年3月2日閲覧。

- ^ “GHJP Report Calls for Reinvestment to Revive Public Health in the U.S.” (英語). Yale Law School. (2021年6月7日) 2022年3月2日閲覧。

- ^ Eager, William; Herman, David; House, Margaret; Robinson, Leah; Williams, Christopher (2021). Confronting a legacy of scarcity: a plan for America's reinvestment in U.S. public health. Yale School of Public Health

- ^ “The Impact of Chronic Underfunding on America's Public Health System: Trends, Risks, and Recommendations, 2021”. Trust for America's Health (2021年5月7日). 2022年3月2日閲覧。

公衆衛生と同じ種類の言葉

固有名詞の分類

- 公衆衛生のページへのリンク