髄膜炎

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2024/02/25 13:28 UTC 版)

| 髄膜炎 | |

|---|---|

| |

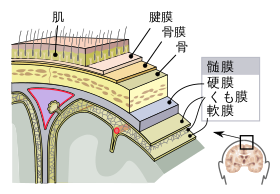

| 中枢神経の髄膜の構造 | |

| 概要 | |

| 診療科 | 神経学, 感染症内科学 |

| 分類および外部参照情報 | |

| ICD-10 | G00–G03 |

| ICD-9-CM | 320–322 |

| DiseasesDB | 22543 |

| MedlinePlus | 000680 |

| eMedicine | med/2613 emerg/309 emerg/390 |

| Patient UK | 髄膜炎 |

| MeSH | D008581 |

最も散見される髄膜炎の症状は頭痛、項部硬直であり、発熱や錯乱、変性意識状態、嘔吐、光を嫌がる(羞明)、騒音に耐えられなくなる(音恐怖)などといった症状を伴う。また、ビオー呼吸と呼ばれる、間欠的に無呼吸の時間が現れる特殊な呼吸の状態が一時的に見られる場合もある。小児例では不機嫌や傾眠などの非特異的症状が目立つものの、大泉門が閉鎖していない場合は膨らむことがある。

皮疹がみられる場合、髄膜炎の特定の病因を示唆している場合がある。例えば髄膜炎菌性髄膜炎には特徴的な皮疹がみられる[1][4]。

脊柱管に針を刺入し、脳および脊髄を包む脳脊髄液(CSF)のサンプルを採取する腰椎穿刺によって髄膜炎が陽性か陰性かを診断する。CSF検査は医療研究機関で実施されている[3]。

急性髄膜炎の一次治療は抗生物質を速やかに投与することであり、抗ウイルス薬を用いることもある。炎症の悪化から合併症を併発するのを予防するため、副腎皮質ホルモンを投与してもよい[3][4]。髄膜炎は、とりわけ治療が遅れた場合に難聴、てんかん、水頭症、認知障害等の長期的な後遺症を遺すことがある[1][4]。髄膜炎のタイプによっては(髄膜炎菌、インフルエンザ菌b型、肺炎レンサ球菌、流行性耳下腺炎(おたふくかぜ)ウイルス感染に起因するものなど)予防接種によって予防できるものがある[1]。

徴候と症状

臨床像

成人の髄膜炎に最も多い症状は重度の頭痛であり、細菌性髄膜炎の90%近くに認められる。次いで項部硬直(首の筋緊張、硬直により首を他動的に前へ曲げられなくなる)がみられる[5]。項部硬直、急な高熱、意識障害を髄膜炎の3徴というが、この3徴が全てみられるのは細菌性髄膜炎患者の44 - 46%程度に過ぎない[5][6]。この3徴のいずれもみられない場合、髄膜炎の可能性は極めて低い[6]。これ以外の徴候としては、羞明(明るい光を嫌がる)や音恐怖(大きな音に耐えられない)が挙げられる。

ただし、乳幼児では先に挙げたような症状がみられないことが多く、不機嫌な様子や、具合が悪そうな様子を見せるにとどまることがある[1]。6か月までの乳児の場合、泉門(乳児の頭頂部にある柔らかい部分)に膨隆がみられることがある。これより重症度の低い乳幼児の髄膜炎を診断する際には、脚の痛みや末端部の冷え、肌の色の異常などが手掛かりとなる[7][8]。

項部硬直は成人の細菌性髄膜炎患者の70%にみられる[6]。このほか、ケルニッヒ徴候やブルジンスキー徴候も髄膜症を示す徴候である。ケルニッヒ徴候を評価する際には、患者を仰臥位に寝かせ、股関節および膝関節をそれぞれ90度に曲げる。膝関節を他動的に伸展させようとすると痛みのため伸展制限が出る場合、ケルニッヒ徴候陽性である。また、首を前屈させると膝関節と股関節が自然に屈曲する場合、ブルジンスキー徴候陽性である。いずれも髄膜炎のスクリーニングによく用いられるが、感度は限定的である[6][9]。一方で髄膜炎に対して非常に高い特異度を示し、別の疾患ではほとんどみられない[6]。

これ以外にも、発熱と頭痛を訴える患者にはjolt accentuation(ジョルトサイン)と呼ばれる手技が髄膜炎の有無を判断する助けになる。患者に「イヤイヤをする」ように頭部を左右に水平方向にすばやく回旋・往復させたときに頭痛が増悪しなければ、髄膜炎の可能性は低い[6]。これは感度90%、特異度60%ともいわれ、除外診断に極めて有用である[10](髄膜炎での感度 97%, 特異度 60%との報告もある[11])。

Neisseria meningitidis (髄膜炎菌)という細菌によって惹き起こされる髄膜炎(髄膜炎菌性髄膜炎)は、初期に急速に広がる点状出血性皮疹によってこれ以外の髄膜炎と区別できる[7]。この皮疹は、胴、脚、粘膜、結膜、(時に掌や足の裏)にみられ、多数の小さく不定形な紫色ないし赤色の点("点状出血")である。一般的に紫斑であり、指やガラスのコップで押さえても赤みは消失しない。この皮疹は髄膜炎菌性髄膜炎に必ずみられるものではないものの、比較的特異的といえる。ただし、時に他の細菌による髄膜炎にも発現することがある[1]。

髄膜炎の原因を探る手掛かりとしては、この他に手足口病や性器ヘルペスにみられるような皮膚の徴候が挙げられ、いずれもさまざまなウイルス性髄膜炎に認められる[12]。

初期の合併症

髄膜炎の初期段階で、別の問題が生じることがある。これには個別の治療を必要とし、重症化したり予後が悪化したりする場合もある。感染が敗血症、全身性炎症反応症候群、血圧低下、頻脈、高熱や低体温、呼吸促拍等を惹き起こす場合がある。初期段階に過度の低血圧がみられることがあり、他臓器に充分な血液を供給できなくなる。特に髄膜炎菌性髄膜炎に多いが、これに限られない[1]。播種性血管内凝固症候群に陥ると血液凝固が過度に活性化され、臓器への血流が阻害されると同時に出血リスクが増大する。髄膜炎菌性疾患では時に四肢の壊疽に至ることもある[1]。重度の髄膜炎菌および肺炎球菌感染では副腎から大量出血してウォーターハウス・フリードリヒセン症候群を発症することがあり、多くは致死的である[13]。

脳組織が増大し頭蓋骨内部の圧力が亢進して、膨張した脳が頭蓋底から押し出され脳ヘルニアになる場合があり、意識レベルの低下、対光反射の消失、異常肢位によって気づくことが多い[4]。また、脳組織の炎症によって脳周囲のCSFの正常な流れが阻害される場合がある(水頭症) [4]。

小児ではさまざまな原因からてんかん発作を来たす。てんかん発作は髄膜炎の初期段階によくみられ(全症例の30%)、必ずしも根本的な原因を示すものではなく[3]、頭蓋内圧亢進や脳組織の炎症から生じる[4]。部分発作(腕や脚、体の一部分に生じるてんかん発作)、持続性発作、遅発性発作などの投薬によるコントロールの難しい発作があると長期転帰が不良になりやすい[1]。

また、髄膜の炎症により脳神経 (脳幹から頭部および頸部に分布し眼球の動きや顔面筋、聴覚をコントロールする神経群)が異常を来たすことがある[1][6]。視覚系の諸症状および難聴は髄膜炎の症状発現後しばらく持続する[1]。脳の炎症 (脳炎)や脳血管の炎症(脳血管炎)があると、静脈内の血栓の形成 (脳静脈洞血栓症)と同様に脱力感や感覚の麻痺、損傷を受けた脳の部位に応じた身体の異常運動や機能異常がみられるようになる[1][4]。

原因

髄膜炎は通常微生物感染によって引き起こされる。ほとんどはウイルスによるもので[6]、次いで細菌、真菌、原生動物によるものが多い[2]。

また、感染によらないさまざまな原因によって発症する場合もある[2]。「無菌性髄膜炎」とは細菌感染が確認されない髄膜炎の症例を指す。このタイプの髄膜炎は通常ウイルスによって惹き起こされるものであるが、時に細菌感染を原因とするものもあり、その場合部分的に治療されて細菌が髄膜から消失しているか、髄膜に隣接する空間が病巣となっている場合などがある(例:副鼻腔炎)。心内膜炎(血流に乗って細菌群が広がる心臓弁の感染)もまた無菌性髄膜炎の原因となる場合がある。Treponema pallidum(梅毒の原因菌)やBorrelia burgdorferi(ライム病の原因菌)をはじめとするスピロヘータ感染から無菌性髄膜炎感染を発症することもある。脳マラリアやアメーバ性髄膜炎(フォーラーネグレリア等の自然界の水源に存在するアメーバ感染による髄膜炎)も報告されている[2]。

細菌性髄膜炎

細菌性髄膜炎または化膿性髄膜炎と呼ぶ。脳に細菌が入る事もあり、脳障害になる恐れもある。

腰椎穿刺施行にて得られた脳脊髄液において、菌体を認め、好中球の増加、ブドウ糖の減少を認めることが多い。症状は最も激烈で、適切な治療が速やかに要求される。

髄膜炎菌は欧米では重要な起炎菌であるが、日本では少ない。

ウイルス性髄膜炎

髄膜炎を惹き起こすウイルスにはエンテロウイルス、単純ヘルペスウイルス2型(まれに1型も)、水痘・帯状疱疹ウイルス(水痘・帯状疱疹の原因ウイルス)、流行性耳下腺炎(おたふくかぜ)ウイルス、HIV、リンパ球性脈絡髄膜炎ウイルス[12]などがある。年長小児(幼稚園児 - 小中学生)に多い。根本原因を解決することはできないが、頭痛や嘔吐に対する対症療法を行っていれば、ほとんどの場合、自然軽快傾向を示す。死亡したり後遺症を残すことはまれである。

真菌性髄膜炎

真菌性髄膜炎の危険因子は数多く存在し、免疫抑制剤(臓器移植後に使用するもの等)、HIV/AIDS [14]、加齢による免疫機能の低下[15]などが挙げられる。正常な免疫機能が備わっていれば発症の頻度は低いが[16]、過去に薬物汚染による発生例が存在する[17]。症状の発現は一般的に緩やかで、診断の少なくとも1~2週間前から頭痛や発熱が認められる[15]。

最もよくみられる真菌性髄膜炎はCryptococcus neoformansによるクリプトコッカス髄膜炎である[18]。アフリカではクリプトコッカス髄膜炎は最もよくみられる髄膜炎の原因とされ[19]、アフリカにおけるAIDS関連死の20~25%を占める[20]。これ以外にもHistoplasma capsulatum、Coccidioides immitis、Blastomyces dermatitidisおよびカンジダなどがよくみられる。[15]

寄生虫性髄膜炎

CSF内の好酸球(白血球の一種)優位が認められる場合、寄生虫が原因である可能性が考えられる。最もよくみられるのは広東住血線虫、顎口虫、住血吸虫であり、嚢虫症、トキソカラ症、アライグマ回虫症、肺吸虫症の諸症状や、さらに稀な症状、非感染性の症状が同時に認められることが多い[21]。

非感染性髄膜炎

髄膜炎は非感染性の原因によっても発症することがある。髄膜に広がる癌(悪性または腫瘍性髄膜炎)[22]や医薬品 (主に非ステロイド性抗炎症薬、抗生物質、静注用免疫グロブリン等)を原因とするものである[23]。また、サルコイドーシス(この場合神経サルコイドーシスと呼ばれる)、全身性エリテマトーデス等の膠原病や、ベーチェット病をはじめとする血管炎症候群(血管壁の炎症)等の炎症症状によっても惹き起こされることがある[2]。

このほか、類表皮嚢胞や類皮嚢胞もクモ膜下腔に刺激性物質を放出して髄膜炎を誘発することがある[2][24]。

モラレ髄膜炎は再発を繰り返す無菌性髄膜炎の一症候で、単純ヘルペスウイルス2型が原因であると考えられている。まれに偏頭痛が髄膜炎を惹き起こすことがあるが、これは他の原因が除外されて初めて診断できるものである[2]。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Sáez-Llorens X, McCracken GH (June 2003). “Bacterial meningitis in children”. Lancet 361 (9375): 2139–48. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13693-8. PMID 12826449.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ginsberg L (March 2004). “Difficult and recurrent meningitis”. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 75 Suppl 1 (90001): i16–21. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.034272. PMC 1765649. PMID 14978146.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL et al. (November 2004). “Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis”. Clinical Infectious Diseases 39 (9): 1267–84. doi:10.1086/425368. PMID 15494903.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s van de Beek D, de Gans J, Tunkel AR, Wijdicks EF (January 2006). “Community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults”. The New England Journal of Medicine 354 (1): 44–53. doi:10.1056/NEJMra052116. PMID 16394301.

- ^ a b van de Beek D, de Gans J, Spanjaard L, Weisfelt M, Reitsma JB, Vermeulen M (October 2004). “Clinical features and prognostic factors in adults with bacterial meningitis” (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine 351 (18): 1849–59. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040845. PMID 15509818.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Attia J, Hatala R, Cook DJ, Wong JG (July 1999). “The rational clinical examination. Does this adult patient have acute meningitis?”. Journal of the American Medical Association 282 (2): 175–81. doi:10.1001/jama.282.2.175. PMID 10411200.

- ^ a b c Theilen U, Wilson L, Wilson G, Beattie JO, Qureshi S, Simpson D (June 2008). “Management of invasive meningococcal disease in children and young people: Summary of SIGN guidelines”. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 336 (7657): 1367–70. doi:10.1136/bmj.a129. PMC 2427067. PMID 18556318.

- ^ Management of invasive meningococcal disease in children and young people. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). (May 2008). ISBN 978-1-905813-31-5

- ^ Thomas KE, Hasbun R, Jekel J, Quagliarello VJ (July 2002). “The diagnostic accuracy of Kernig's sign,Brudzinski neck sign, and 項部硬直 in adults with suspected meningitis”. Clinical Infectious Diseases 35 (1): 46–52. doi:10.1086/340979. PMID 12060874.

- ^ 岡田定 編, 「最速!聖路加診断術」, p45.

- ^ Tokuda Y, et al. Internal Med. 2009;48:537-43.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Logan SA, MacMahon E (January 2008). “Viral meningitis”. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 336 (7634): 36–40. doi:10.1136/bmj.39409.673657.AE. PMC 2174764. PMID 18174598.

- ^ Varon J, Chen K, Sternbach GL (1998). “Rupert Waterhouse and Carl Friderichsen: adrenal apoplexy”. J Emerg Med 16 (4): 643–7. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(98)00061-4. PMID 9696186.

- ^ Raman Sharma R (2010). “Fungal infections of the nervous system: current perspective and controversies in management”. International journal of surgery (London, England) 8 (8): 591–601. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.07.293. PMID 20673817.

- ^ a b c Sirven JI, Malamut BL (2008). Clinical neurology of the older adult (2nd ed. ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 439. ISBN 9780781769471

- ^ Honda H, Warren DK (2009 Sep). “Central nervous system infections: meningitis and brain abscess”. Infectious disease clinics of North America 23 (3): 609–23. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2009.04.009. PMID 19665086.

- ^ Kauffman CA, Pappas PG, Patterson TF (19 October 2012). “Fungal infections associated with contaminated methyprednisolone injections—preliminary report”. New England Journal of Medicine Online first. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1212617.

- ^ Kauffman CA, Pappas PG, Sobel JD, Dismukes WE. Essentials of clinical mycology (2nd ed. ed.). New York: Springer. p. 77. ISBN 9781441966391

- ^ Kauffman CA, Pappas PG, Sobel JD, Dismukes WE. Essentials of clinical mycology (2nd ed. ed.). New York: Springer. p. 31. ISBN 9781441966391

- ^ Park, Benjamin J; Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, Chiller TM. (2009年2月1日). “Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS”. AIDS 23 (4): 525–530. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac. PMID 19182676.

- ^ a b Graeff-Teixeira C, da Silva AC, Yoshimura K (Apr 2009). “Update on eosinophilic meningoencephalitis and its clinical relevance”. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 22 (2): 322–48. doi:10.1128/CMR.00044-08. PMC 2668237. PMID 19366917.

- ^ Gleissner B, Chamberlain MC (May 2006). “Neoplastic meningitis”. Lancet Neurol 5 (5): 443–52. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70443-4. PMID 16632315.

- ^ Moris G, Garcia-Monco JC (June 1999). “The Challenge of Drug-Induced Aseptic Meningitis”. Archives of Internal Medicine 159 (11): 1185–94. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.11.1185. PMID 10371226.

- ^ Tebruegge M, Curtis N (July 2008). “Epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis of recurrent bacterial meningitis”. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 21 (3): 519–37. doi:10.1128/CMR.00009-08. PMC 2493086. PMID 18625686.

- ^ Provan, Drew; Andrew Krentz (2005). Oxford Handbook of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-856663-8

- ^ a b c d e Chaudhuri A, Martinez–Martin P, Martin PM et al. (July 2008). “EFNS guideline on the management of community-acquired bacterial meningitis: report of an EFNS Task Force on acute bacterial meningitis in older children and adults”. European Journal of Neurolology 15 (7): 649–59. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02193.x. PMID 18582342.

- ^ a b c d Straus SE, Thorpe KE, Holroyd-Leduc J (October 2006). “How do I perform a lumbar puncture and analyze the results to diagnose bacterial meningitis?”. Journal of the American Medical Association 296 (16): 2012–22. doi:10.1001/jama.296.16.2012. PMID 17062865.

- ^ a b c d e Heyderman RS, Lambert HP, O'Sullivan I, Stuart JM, Taylor BL, Wall RA (February 2003). “Early management of suspected bacterial meningitis and meningococcal septicaemia in adults”. The Journal of infection 46 (2): 75–7. doi:10.1053/jinf.2002.1110. PMID 12634067. – formal guideline at British Infection Society & UK Meningitis Research Trust (2004年12月). “Early management of suspected meningitis and meningococcal septicaemia in immunocompetent adults”. British Infection Society Guidelines. 2008年10月19日閲覧。

- ^ Maconochie I, Baumer H, Stewart ME (2008). MacOnochie, Ian K. ed. “Fluid therapy for acute bacterial meningitis”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004786. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004786.pub3. PMID 18254060. CD004786.

- ^ a b Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F et al (2010). “Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america”. Clinical Infectious Diseases 50 (3): 291–322. doi:10.1086/649858. PMID 20047480.

- ^ Sakushima, K; Hayashino, Y; Kawaguchi, T; Jackson, JL; Fukuhara, S (2011 Apr). “Diagnostic accuracy of cerebrospinal fluid lactate for differentiating bacterial meningitis from aseptic meningitis: a meta-analysis.”. The Journal of infection 62 (4): 255–62. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2011.02.010. PMID 21382412.

- ^ Thwaites G, Chau TT, Mai NT, Drobniewski F, McAdam K, Farrar J (March 2000). “Tuberculous meningitis”. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 68 (3): 289–99. doi:10.1136/jnnp.68.3.289. PMC 1736815. PMID 10675209.

- ^ a b c Bicanic T, Harrison TS (2004). “Cryptococcal meningitis”. British Medical Bulletin 72 (1): 99–118. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldh043. PMID 15838017.

- ^ Sloan D, Dlamini S, Paul N, Dedicoat M (2008). Sloan, Derek. ed. “Treatment of acute cryptococcal meningitis in HIV infected adults, with an emphasis on resource-limited settings”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD005647. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005647.pub2. PMID 18843697. CD005647.

- ^ Warrell DA, Farrar JJ, Crook DWM (2003). “24.14.1 Bacterial meningitis”. Oxford Textbook of Medicine Volume 3 (Fourth ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 1115–29. ISBN 0-19-852787-X

- ^ a b c “CDC – Meningitis: Transmission”. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2009年8月6日). 2011年6月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e Segal S, Pollard AJ (2004). “Vaccines against bacterial meningitis”. British Medical Bulletin 72 (1): 65–81. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldh041. PMID 15802609.

- ^ a b Peltola H (April 2000). “Worldwide Haemophilus influenzae type b disease at the beginning of the 21st century: global analysis of the disease burden 25 years after the use of the polysaccharide vaccine and a decade after the advent of conjugates”. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 13 (2): 302–17. doi:10.1128/CMR.13.2.302-317.2000. PMC 100154. PMID 10756001.

- ^ a b c Harrison LH (January 2006). “Prospects for vaccine prevention of meningococcal infection”. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 19 (1): 142–64. doi:10.1128/CMR.19.1.142-164.2006. PMC 1360272. PMID 16418528.

- ^ a b Wilder-Smith A (October 2007). “Meningococcal vaccine in travelers”. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 20 (5): 454–60. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282a64700. PMID 17762777.

- ^ WHO (September 2000). “Detecting meningococcal meningitis epidemics in highly-endemic African countries” (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record 75 (38): 306–9. PMID 11045076.

- ^ Bishai, DM; Champion, C; Steele, ME; Thompson, L (2011 Jun). “Product development partnerships hit their stride: lessons from developing a meningitis vaccine for Africa.”. Health affairs (Project Hope) 30 (6): 1058–64. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0295. PMID 21653957.

- ^ Marc LaForce, F; Ravenscroft, N; Djingarey, M; Viviani, S (2009 Jun 24). “Epidemic meningitis due to Group A Neisseria meningitidis in the African meningitis belt: a persistent problem with an imminent solution.”. Vaccine 27 Suppl 2: B13-9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.062. PMID 19477559.

- ^ a b Weisfelt M, de Gans J, van der Poll T, van de Beek D (April 2006). “Pneumococcal meningitis in adults: new approaches to management and prevention”. Lancet Neurol 5 (4): 332–42. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70409-4. PMID 16545750.

- ^ a b Zalmanovici Trestioreanu, A; Fraser, A; Gafter-Gvili, A; Paul, M; Leibovici, L (2011 Aug 10). “Antibiotics for preventing meningococcal infections.”. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (8): CD004785. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004785.pub4. PMID 21833949.

- ^ a b Ratilal, BO; Costa, J; Sampaio, C; Pappamikail, L (2011 Aug 10). “Antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing meningitis in patients with basilar skull fractures.”. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (8): CD004884. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004884.pub3. PMID 21833952.

- ^ “Meningitis and Encephalitis Fact Sheet”. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (2007年12月11日). 2009年4月27日閲覧。

- ^ Gottfredsson M, Perfect JR (2000). “Fungal meningitis”. Seminars in Neurology 20 (3): 307–22. doi:10.1055/s-2000-9394. PMID 11051295.

- ^ “Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002” (xls). World Health Organization (WHO) (2002年). 2009年11月11日閲覧。

- ^ Richardson MP, Reid A, Tarlow MJ, Rudd PT (February 1997). “Hearing loss during bacterial meningitis”. Archives of Disease in Childhood 76 (2): 134–38. doi:10.1136/adc.76.2.134. PMC 1717058. PMID 9068303.

- ^ Lapeyssonnie L (1963). “Cerebrospinal meningitis in Africa”. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 28: SUPPL:1–114. PMC 2554630. PMID 14259333.

- ^ Greenwood B (1999). “Manson Lecture. Meningococcal meningitis in Africa”. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93 (4): 341–53. doi:10.1016/S0035-9203(99)90106-2. PMID 10674069.

- ^ a b c World Health Organization (1998) (PDF). Control of epidemic meningococcal disease, practical guidelines, 2nd edition, WHO/EMC/BA/98. 3. pp. 1–83

- ^ WHO (2003). “Detecting meningococcal meningitis epidemics in highly-endemic African countries” (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record 78 (33): 294–6. PMID 14509123.

- ^ a b Arthur Earl Walker, Edward R. Laws, George B. Udvarhelyi (1998). “Infections and inflammatory involvement of the CNS”. The Genesis of Neuroscience. Thieme. pp. 219–21. ISBN 1-879284-62-6

- ^ Whytt R (1768). Observations on the Dropsy in the Brain. Edinburgh: J. Balfour

- ^ a b c Greenwood B (June 2006). “100 years of epidemic meningitis in West Africa – has anything changed?” (PDF). Tropical Medicine & International health: TM & IH 11 (6): 773–80. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01639.x. PMID 16771997.

- ^ Vieusseux G (1806). “Mémoire sur le Maladie qui a regne à Génève au printemps de 1805” (French). Journal de Médecine, de Chirurgie et de Pharmacologie (Bruxelles) 11: 50–53.

- ^ Weichselbaum A (1887). “Ueber die Aetiologie der akuten Meningitis cerebro-spinalis” (German). Fortschrift der Medizin 5: 573–583.

- ^ Flexner S (1913). “The results of the serum treatment in thirteen hundred cases of epidemic meningitis”. J Exp Med 17 (5): 553–76. doi:10.1084/jem.17.5.553. PMC 2125091. PMID 19867668.

- ^ a b Swartz MN (October 2004). “Bacterial meningitis—a view of the past 90 years”. The New England Journal of Medicine 351 (18): 1826–28. doi:10.1056/NEJMp048246. PMID 15509815.

- ^ Rosenberg DH, Arling PA (1944). “in the treatment of meningitis”. Journal of the American Medical Association 125 (15): 1011–17. doi:10.1001/jama.1944.02850330009002. reproduced in Rosenberg DH, Arling PA (April 1984). “Penicillin in the treatment of meningitis”. Journal of the American Medical Association 251 (14): 1870–6. doi:10.1001/jama.251.14.1870. PMID 6366279.

- ^ de Gans J, van de Beek D (November 2002). “Dexamethasone in adults with bacterial meningitis” (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine 347 (20): 1549–56. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021334. PMID 12432041.

- ^ Brouwer MC, McIntyre P, de Gans J, Prasad K, van de Beek D (2010). Van De Beek, Diederik. ed. “Corticosteroids for acute bacterial meningitis”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD004405. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004405.pub3. PMID 20824838. CD004405.

- ^ 所見からせまる脳MRI ISBN 9784879623737

- ^ 上原すゞ子: 欧米におけるインフルエンザ菌b型(Hib)感染症の激減とHibワクチン. 日小児会誌 100: 1693-1696, 1996.

髄膜炎と同じ種類の言葉

固有名詞の分類

- 髄膜炎のページへのリンク