原子

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2024/03/08 23:44 UTC 版)

構造

亜原子粒子

原子(atom)という言葉はもともと、小さな粒子に切断できない粒子を意味するが、現代の科学的用法では、原子はさまざまな亜原子粒子(英: subatomic particles)から構成される物質の基本的な構成要素を指す。原子を構成する粒子は、電子、陽子、そして中性子である。

電子は負の電荷を持ち、質量が 9.11×10−31 kg で、これらの粒子の中で圧倒的に小さく、そのため利用可能な技術で大きさを測定することができない[43]。ニュートリノの質量が発見されるまで、電子は正の静止質量が測定された最も軽い粒子であった。通常の条件下において、電子は、正電荷を帯びた原子核に、その反対電荷から生じる引力によって束縛される。原子の電子数がその原子番号より大きい(または小さい)場合、原子は全体として負(または正)に帯電し、帯電した原子はイオンと呼ばれる。電子は19世紀後半から知られていたが、J.J.トムソンの貢献が大きかった(素粒子物理学の歴史を参照)。

陽子は正の電荷を持ち、質量は1.6726×10−27 kg、電子の質量の1,836倍である。原子内の陽子の数を原子番号という。アーネスト・ラザフォードは、1917-1919年にかけ、アルファ粒子の衝突を受けた窒素から水素原子核と考えられるものが放出されることを観測した。1920年までに、彼は水素原子核が原子内の別個の粒子であると考え、これを陽子と名付けた。

中性子は電荷を持たず、自由質量は 1.6749×10−27 kgで、電子の質量の1,839倍である[44][45]。中性子は3つの構成粒子の中で最も重いが、その質量は核結合エネルギーによって減る可能性がある。中性子と陽子(総称して核子という)は、どちらも 2.5×10−15 m 程度の大きさを持つが、これらの粒子の「表面」は明確に定義されていない[46]。中性子は1932年にイギリスの物理学者ジェームズ・チャドウィックによって発見された。

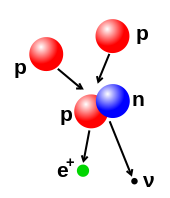

物理学の標準モデルでは、電子は内部構造を持たない真の素粒子であり、陽子と中性子はクォークと呼ばれる素粒子から構成される複合粒子である。原子には2種類のクォークがあり、それぞれが分数の電荷を持っている。陽子は、2個のアップクォーク(それぞれの電荷は+2/3)と1個のダウンクォーク(電荷は−1/3)で構成されている。中性子は、1個のアップクォークと2個のダウンクォークで構成されている。この区別で、2種類の粒子の質量と電荷の違いが説明される[47][48]。

クォークは、グルーオンを介した強い相互作用(強い力ともいう)によって結合している。陽子と中性子は、原子核の中で核力によって互いに結びついている。核力は強い力が残留したもので、その範囲や性質は多少異なる(詳しくは核力(英語版)を参照)。グルーオンは、物理的な力を媒介する素粒子であるゲージ粒子の一種である[47][48]。

原子核

原子中で、すべての陽子と中性子は結合して、小さな原子核を構成する。原子核の半径はおよそ 原子核内の陽子と中性子の数を変えることができるが、それには強い力が働くため、非常に高いエネルギーを必要とする。核融合は、2つの原子核のエネルギー的な衝突などにより、複数の原子粒子が結合してより重い原子核を形成するときに起こる。たとえば、太陽の中心部では、陽子が相互反発(クーロン障壁)を乗り越えて融合し、1つの原子核を形成するために、3-10 keVのエネルギーを必要とする[53]。核分裂はその逆のプロセスで、通常は放射性崩壊によって原子核が2つの小さな原子核に分裂する。また、原子核は、高エネルギーの亜原子粒子や光子との衝突によっても変化することがある。これによって原子核内の陽子の数が変わると、原子は別の化学元素に変化する[54][55]。

核融合反応後の原子核の質量が、個々の粒子の合計質量よりも小さい場合、2つの質量差は、アルベルト・アインシュタインの質量とエネルギー等価性の式、e=mc2(ここで m は質量損失、 c は光速)で説明されるように、利用可能なエネルギーの一種(ガンマ線やベータ粒子の運動エネルギーなど)として放出される。この欠損は新しい原子核の結合エネルギーの一部であり、融合粒子が分離するためにこのエネルギーを必要とする状態で一緒に留まるのは、このエネルギーの回復不可能な損失のためである[56]。

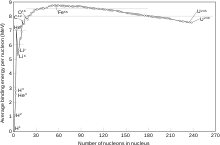

鉄やニッケルよりも原子番号が小さな原子核(核子数の合計が約60以下)を作り出す2個の原子核の核融合は、通常、発熱プロセスであり、2つの原子核を融合させるのに必要なエネルギーよりも多くのエネルギーを放出する[57]。恒星の核融合を自立反応にしているのは、このエネルギー放出プロセスである。より重い原子核では、核子あたりの結合エネルギーは減少し始める(上のグラフを参照)。このことは、原子番号が約26より大きく、質量数が約60より大きな原子核を生成する核融合プロセスは吸熱プロセスであることを意味する。したがって、より質量が大きな原子核は、恒星の静水圧平衡を維持するのに必要なエネルギーを生み出す核融合反応を起こすことができない[52]。

電子雲

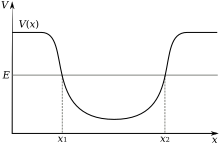

原子内の電子は、電磁気力によって原子核内の陽子に引き寄せられる。この力によって電子は、小さな原子核を取り囲む静電ポテンシャル井戸の中に束縛され、電子が脱出するためには外部のエネルギー源が必要となる。電子が原子核に近づくほど、この引力は大きくなる。したがって、ポテンシャル井戸の中心付近に束縛された電子は、それよりも離れた位置にある電子よりも、脱出するのに多くのエネルギーを必要とする。

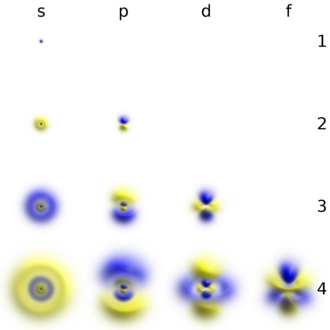

電子は、他の粒子と同様に、粒子と波の両方の性質を持っている。電子雲は、ポテンシャル井戸の内側にある領域で、各電子が一種の三次元定在波(原子核に対して相対的に動かない波形)を形成している。この挙動は原子軌道によって規定される。原子軌道とは、電子の位置を測定したときに、その電子が特定の位置にあるように見える確率を記述する数学的関数である[58]。原子核の周りには、このような離散的な(または量子化された)軌道の集合だけが存在する(他の考えられる波動パターンは、より安定した形へと急速に減衰するため)[59]。軌道は1つまたは複数のリング構造またはノード構造を持つことができ、大きさ、形状、方向がそれぞれ異なる[60]。

それぞれの原子軌道は、電子の特定のエネルギー準位に対応している。電子は、新しい量子状態に遷移するのに十分なエネルギーの光子を吸収することで、その状態をより高いエネルギー準位に変えることができる。同様に、高いエネルギー準位にある電子は、自然放出によって余剰なエネルギーを光子として放射しながら、低いエネルギー準位に落ちることができる。量子状態のエネルギーの違いによって規定されるこれらの特徴的なエネルギー値が、原子スペクトル線 (en:英語版) が生じる原因である[59]。

原子から電子を除去または追加するのに必要なエネルギー量(電子結合エネルギー (en:英語版) )は、核子の結合エネルギーよりもはるかに小さい。たとえば、水素原子から基底状態の電子を取り除くのに必要なエネルギーはわずか 13.6 eV であるのに対し[61]、重水素の原子核を分裂させるのに必要なエネルギーは 223万eV に達する[62]。陽子と電子が同数であれば、原子は電気的に中性である。電子が不足または過剰な原子はイオンと呼ばれる。原子核から最も遠い電子は、近くにある別の原子に移動したり、原子間で共有されることがある。この機構により、原子が結合して分子を構成したり、イオン結晶やネットワーク共有結合結晶のような他の種類の化合物と結合することができる[63]。

注釈

- ^ 否定語「a-」と「切断」を意味する「τομή」の組み合わせ。

- ^ 説明をわかりやすくするため、酸化鉄(II)の式を、従来のFeOではなく「Fe2O2」と表記した。

- ^ 通常、円運動する電荷は、加速時に電磁波を放出することで運動エネルギーを失う (シンクロトロン放射を参照)

- ^ 最近の更新情報については、ブルックヘブン国立研究所の Interactive Chart of Nuclides Archived 25 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine. を参照。

- ^ 1カラットは200 mg。定義によれば、炭素12は1 molあたり 0.012 kg である。アボガドロ定数は1 mol当たり6×1023個の原子を含むと定義される。

出典

- ^ “Atom | Glossary | Basic References | NRC Library”. NRC.gov. 米国原子力規制委員会. 2023年10月22日閲覧。 “Atom - The smallest particle of an element that cannot be divided or broken up by chemical means. It consists of a central core (or nucleus), containing protons and neutrons, with electrons revolving in orbits in the region surrounding the nucleus.”

- ^ Pullman, Bernard (1998). The Atom in the History of Human Thought. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-0-19-515040-7. オリジナルの5 February 2021時点におけるアーカイブ。 2020年10月25日閲覧。

- ^ Melsen (1952). From Atomos to Atom, pp. 18–19

- ^ Pullman (1998). The Atom in the History of Human Thought, p. 198: "Dalton reaffirmed that atoms are indivisible and indestructible and are the ultimate constituents of matter."

- ^ Dalton (1817). A New System of Chemical Philosophy vol. 2, p. 36

- ^ Melsen (1952). From Atomos to Atom, p. 137

- ^ Dalton (1817). A New System of Chemical Philosophy vol. 2, p. 28

- ^ Millington (1906). John Dalton, p. 113

- ^ Dalton (1808). A New System of Chemical Philosophy vol. 1, pp. 316–319

- ^ Holbrow et al. (2010). Modern Introductory Physics, pp. 65–66

- ^ Pullman (1998). The Atom in the History of Human Thought, p. 230

- ^ Melsen (1952). From Atomos to Atom, pp. 147–148

- ^ Henry Enfield Roscoe, Carl Schorlemmer (1895). A Treatise on Chemistry, Volume 3, Part 1, pp. 121–122

- ^ Einstein, A. (1905). “Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen”. Annalen der Physik 322 (8): 549–560. Bibcode: 1905AnP...322..549E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053220806. hdl:10915/2785.

- ^ “The Nobel Prize in Physics 1926” (英語). NobelPrize.org. 2023年2月8日閲覧。

- ^ Perrin (1909). Brownian Movement and Molecular Reality, p. 50

- ^ Thomson, J.J. (August 1901). “On bodies smaller than atoms”. The Popular Science Monthly: 323–335. オリジナルの1 December 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。 2009年6月21日閲覧。.

- ^ "The Mechanism Of Conduction In Metals" Archived 25 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine., Think Quest.

- ^ Navarro (2012). A History of the Electron, p. 94

- ^ a b Heilbron (2003). Ernest Rutherford and the Explosion of Atoms, pp. 64–68

- ^ “Frederick Soddy, The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1921”. ノーベル財団. 2008年4月9日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月18日閲覧。

- ^ Thomson, Joseph John (1913). “Rays of positive electricity”. Proceedings of the Royal Society. A 89 (607): 1–20. Bibcode: 1913RSPSA..89....1T. doi:10.1098/rspa.1913.0057. オリジナルの4 November 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Stern, David P. (2005年5月16日). “The Atomic Nucleus and Bohr's Early Model of the Atom”. NASA/ゴダード宇宙飛行センター. 2007年8月20日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2022年2月17日閲覧。

- ^ Bohr, Niels (1922年12月11日). “Niels Bohr, The Nobel Prize in Physics 1922, Nobel Lecture”. ノーベル財団. 2008年4月15日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年2月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Pais, Abraham (1986). Inward Bound: Of Matter and Forces in the Physical World. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 228–230. ISBN 978-0-19-851971-3

- ^ Lewis, Gilbert N. (1916). “The Atom and the Molecule”. Journal of the American Chemical Society 38 (4): 762–786. doi:10.1021/ja02261a002. オリジナルの25 August 2019時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Scerri, Eric R. (2007). The periodic table: its story and its significance. Oxford University Press US. pp. 205–226. ISBN 978-0-19-530573-9

- ^ Langmuir, Irving (1919). “The Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms and Molecules”. Journal of the American Chemical Society 41 (6): 868–934. doi:10.1021/ja02227a002. オリジナルの21 June 2019時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ McEvoy, J. P.; Zarate, Oscar (2004). Introducing Quantum Theory. Totem Books. pp. 110–114. ISBN 978-1-84046-577-8

- ^ Kozłowski, Miroslaw (2019年). “The Schrödinger equation A History”. 2020年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ Chad Orzel (2014年9月16日). “What is the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle?”. TED-Ed. 2015年9月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2015年10月26日閲覧。

- ^ Brown, Kevin (2007年). “The Hydrogen Atom”. MathPages. 2012年9月5日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月2日閲覧。

- ^ Harrison, David M. (2000年). “The Development of Quantum Mechanics”. トロント大学. 2007年12月25日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月2日閲覧。

- ^ Aston, Francis W. (1920). “The constitution of atmospheric neon”. Philosophical Magazine 39 (6): 449–455. doi:10.1080/14786440408636058. オリジナルの27 April 2021時点におけるアーカイブ。 2020年10月25日閲覧。.

- ^ Chadwick, James (1935年12月12日). “Nobel Lecture: The Neutron and Its Properties”. ノーベル財団. 2007年10月12日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月2日閲覧。

- ^ Bowden, Mary Ellen (1997). “Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner, and Fritz Strassmann”. Chemical achievers : the human face of the chemical sciences. Philadelphia, PA: Chemical Heritage Foundation. pp. 76–80, 125. ISBN 978-0-941901-12-3

- ^ “Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner, and Fritz Strassmann”. Science History Institute (2016年6月). 2018年3月21日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2018年3月21日閲覧。

- ^ Meitner, Lise; Frisch, Otto Robert (1939). “Disintegration of uranium by neutrons: a new type of nuclear reaction”. Nature 143 (3615): 239–240. Bibcode: 1939Natur.143..239M. doi:10.1038/143239a0.

- ^ Schroeder, M.. “Lise Meitner – Zur 125. Wiederkehr Ihres Geburtstages” (ドイツ語). 2011年7月19日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2009年6月4日閲覧。

- ^ Crawford, E.; Sime, Ruth Lewin; Walker, Mark (1997). “A Nobel tale of postwar injustice”. Physics Today 50 (9): 26–32. Bibcode: 1997PhT....50i..26C. doi:10.1063/1.881933.

- ^ Kullander, Sven (2001年8月28日). “Accelerators and Nobel Laureates”. ノーベル財団. 2008年4月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月31日閲覧。

- ^ “The Nobel Prize in Physics 1990”. ノーベル財団 (1990年10月17日). 2008年5月14日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月31日閲覧。

- ^ Demtröder, Wolfgang (2002). Atoms, Molecules and Photons: An Introduction to Atomic- Molecular- and Quantum Physics (1st ed.). Springer. pp. 39–42. ISBN 978-3-540-20631-6. OCLC 181435713

- ^ Woan, Graham (2000). The Cambridge Handbook of Physics. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-521-57507-2. OCLC 224032426

- ^ Mohr, P.J.; Taylor, B.N. and Newell, D.B. (2014), "The 2014 CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants" Archived 11 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. (Web Version 7.0). The database was developed by J. Baker, M. Douma, and S. Kotochigova. (2014). National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, Maryland 20899.

- ^ MacGregor, Malcolm H. (1992). The Enigmatic Electron. Oxford University Press. pp. 33–37. ISBN 978-0-19-521833-6. OCLC 223372888

- ^ a b Particle Data Group (2002年). “The Particle Adventure”. Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. 2007年1月4日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月3日閲覧。

- ^ a b Schombert, James (2006年4月18日). “Elementary Particles”. University of Oregon. 2011年8月30日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月3日閲覧。

- ^ Jevremovic, Tatjana (2005). Nuclear Principles in Engineering. Springer. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-387-23284-3. OCLC 228384008

- ^ Pfeffer, Jeremy I.; Nir, Shlomo (2000). Modern Physics: An Introductory Text. Imperial College Press. pp. 330–336. ISBN 978-1-86094-250-1. OCLC 45900880

- ^ Wenner, Jennifer M. (2007年10月10日). “How Does Radioactive Decay Work?”. Carleton College. 2008年5月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月9日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Raymond, David (2006年4月7日). “Nuclear Binding Energies”. New Mexico Tech. 2002年12月1日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月3日閲覧。

- ^ Mihos, Chris (2002年7月23日). “Overcoming the Coulomb Barrier”. Case Western Reserve University. 2006年9月12日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年2月13日閲覧。

- ^ Staff (2007年3月30日). “ABC's of Nuclear Science”. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. 2006年12月5日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月3日閲覧。

- ^ Makhijani, Arjun (2001年3月2日). “Basics of Nuclear Physics and Fission”. Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. 2007年1月16日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月3日閲覧。

- ^ Shultis, J. Kenneth; Faw, Richard E. (2002). Fundamentals of Nuclear Science and Engineering. CRC Press. pp. 10–17. ISBN 978-0-8247-0834-4. OCLC 123346507

- ^ Fewell, M.P. (1995). “The atomic nuclide with the highest mean binding energy”. American Journal of Physics 63 (7): 653–658. Bibcode: 1995AmJPh..63..653F. doi:10.1119/1.17828.

- ^ Mulliken, Robert S. (1967). “Spectroscopy, Molecular Orbitals, and Chemical Bonding”. Science 157 (3784): 13–24. Bibcode: 1967Sci...157...13M. doi:10.1126/science.157.3784.13. PMID 5338306.

- ^ a b Brucat, Philip J. (2008年). “The Quantum Atom”. University of Florida. 2006年12月7日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月4日閲覧。

- ^ Manthey, David (2001年). “Atomic Orbitals”. Orbital Central. 2008年1月10日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月22日閲覧。

- ^ Herter, Terry (2006年). “Lecture 8: The Hydrogen Atom”. Cornell University. 2012年2月22日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年2月14日閲覧。

- ^ Bell, R.E.; Elliott, L.G. (1950). “Gamma-Rays from the Reaction H1(n,γ)D2 and the Binding Energy of the Deuteron”. Physical Review 79 (2): 282–285. Bibcode: 1950PhRv...79..282B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.79.282.

- ^ Smirnov, Boris M. (2003). Physics of Atoms and Ions. Springer. pp. 249–272. ISBN 978-0-387-95550-6

- ^ Matis, Howard S. (2000年8月9日). “The Isotopes of Hydrogen”. Guide to the Nuclear Wall Chart. Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. 2007年12月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月2日閲覧。

- ^ Weiss, Rick (2006年10月17日). “Scientists Announce Creation of Atomic Element, the Heaviest Yet”. Washington Post. オリジナルの2011年8月20日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b Sills, Alan D. (2003). Earth Science the Easy Way. Barron's Educational Series. pp. 131–134. ISBN 978-0-7641-2146-3. OCLC 51543743

- ^ Dumé, Belle (2003年4月23日). “Bismuth breaks half-life record for alpha decay”. Physics World. オリジナルの2007年12月14日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Lindsay, Don (2000年7月30日). “Radioactives Missing From The Earth”. Don Lindsay Archive. 2007年4月28日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年5月23日閲覧。

- ^ Tuli, Jagdish K. (2005年4月). “Nuclear Wallet Cards”. National Nuclear Data Center, Brookhaven National Laboratory. 2011年10月3日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年8月6日閲覧。

- ^ CRC Handbook (2002).

- ^ Krane, K. (1988). Introductory Nuclear Physics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 68. ISBN 978-0-471-85914-7

- ^ a b Mills, Ian; Cvitaš, Tomislav; Homann, Klaus; Kallay, Nikola; Kuchitsu, Kozo (1993). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry (2nd ed.). Oxford: International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, Commission on Physiochemical Symbols Terminology and Units, Blackwell Scientific Publications. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-632-03583-0. OCLC 27011505

- ^ Chieh, Chung (2001年1月22日). “Nuclide Stability”. University of Waterloo. 2007年8月30日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月4日閲覧。

- ^ “Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for All Elements”. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2006年12月31日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2007年1月4日閲覧。

- ^ Audi, G.; Wapstra, A.H.; Thibault, C. (2003). “The Ame2003 atomic mass evaluation (II)”. Nuclear Physics A 729 (1): 337–676. Bibcode: 2003NuPhA.729..337A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.003. オリジナルの16 October 2005時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Ghosh, D.C.; Biswas, R. (2002). “Theoretical calculation of Absolute Radii of Atoms and Ions. Part 1. The Atomic Radii”. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 3 (11): 87–113. doi:10.3390/i3020087.

- ^ Shannon, R.D. (1976). “Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides”. Acta Crystallographica A 32 (5): 751–767. Bibcode: 1976AcCrA..32..751S. doi:10.1107/S0567739476001551. オリジナルの14 August 2020時点におけるアーカイブ。 2019年8月25日閲覧。.

- ^ Dong, Judy (1998年). “Diameter of an Atom”. The Physics Factbook. 2007年11月4日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2007年11月19日閲覧。

- ^ Clementi, E.; Raimond, D. L.; Reinhardt, W. P. (1967). “Atomic Screening Constants from SCF Functions. II. Atoms with 37 to 86 Electrons”. Journal of Chemical Physics 47 (4): 1300–1307. Bibcode: 1967JChPh..47.1300C. doi:10.1063/1.1712084.

- ^ Bethe, Hans (1929). “Termaufspaltung in Kristallen”. Annalen der Physik 3 (2): 133–208. Bibcode: 1929AnP...395..133B. doi:10.1002/andp.19293950202.

- ^ Birkholz, Mario (1995). “Crystal-field induced dipoles in heteropolar crystals – I. concept”. Z. Phys. B 96 (3): 325–332. Bibcode: 1995ZPhyB..96..325B. doi:10.1007/BF01313054.

- ^ Birkholz, M.; Rudert, R. (2008). “Interatomic distances in pyrite-structure disulfides – a case for ellipsoidal modeling of sulfur ions”. Physica Status Solidi B 245 (9): 1858–1864. Bibcode: 2008PSSBR.245.1858B. doi:10.1002/pssb.200879532. オリジナルの2 May 2021時点におけるアーカイブ。 2021年5月2日閲覧。.

- ^ Birkholz, M. (2014). “Modeling the Shape of Ions in Pyrite-Type Crystals”. Crystals 4 (3): 390–403. doi:10.3390/cryst4030390.

- ^ Staff (2007年). “Small Miracles: Harnessing nanotechnology”. Oregon State University. 2011年5月21日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月7日閲覧。 – describes the width of a human hair as 105 nm and 10 carbon atoms as spanning 1 nm.

- ^ Padilla, Michael J.; Miaoulis, Ioannis; Cyr, Martha (2002). Prentice Hall Science Explorer: Chemical Building Blocks. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-13-054091-1. OCLC 47925884. "There are 2,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (that's 2 sextillion) atoms of oxygen in one drop of water—and twice as many atoms of hydrogen."

- ^ “The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. I Ch. 1: Atoms in Motion”. 2022年7月30日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2022年5月3日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Radioactivity”. Splung.com. 2007年12月4日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2007年12月19日閲覧。

- ^ L'Annunziata, Michael F. (2003). Handbook of Radioactivity Analysis. Academic Press. pp. 3–56. ISBN 978-0-12-436603-9. OCLC 16212955

- ^ Firestone, Richard B. (2000年5月22日). “Radioactive Decay Modes”. Berkeley Laboratory. 2006年9月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年9月8日閲覧。

- ^ Hornak, J.P. (2006年). “Chapter 3: Spin Physics”. The Basics of NMR. Rochester Institute of Technology. 2007年2月3日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月7日閲覧。

- ^ a b Schroeder, Paul A. (2000年2月25日). “Magnetic Properties”. University of Georgia. 2007年4月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2007年12月14日閲覧。

- ^ Goebel, Greg (2007年9月1日). “[4.3] Magnetic Properties of the Atom”. Elementary Quantum Physics. In The Public Domain website. 2011年6月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月7日閲覧。

- ^ Yarris, Lynn (Spring 1997). “Talking Pictures”. Berkeley Lab Research Review. オリジナルの13 January 2008時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Liang, Z.-P.; Haacke, E.M. (1999). Webster, J.G.. ed. Encyclopedia of Electrical and Electronics Engineering: Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 412–426. ISBN 978-0-471-13946-1

- ^ Zeghbroeck, Bart J. Van (1998年). “Energy levels”. Shippensburg University. 2005年1月15日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月2日閲覧。

- ^ Fowles, Grant R. (1989). Introduction to Modern Optics. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 227–233. ISBN 978-0-486-65957-2. OCLC 18834711

- ^ Martin, W.C. (2007年5月). “Atomic Spectroscopy: A Compendium of Basic Ideas, Notation, Data, and Formulas”. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2007年2月8日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2018年11月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Atomic Emission Spectra – Origin of Spectral Lines”. Avogadro Web Site. 2006年2月28日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2006年8月10日閲覧。

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Richard (2007年2月16日). “Fine structure”. University of Texas at Austin. 2011年9月27日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年2月14日閲覧。

- ^ Weiss, Michael (2001年). “The Zeeman Effect”. University of California-Riverside. 2008年2月2日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月2日閲覧。

- ^ Beyer, H.F.; Shevelko, V.P. (2003). Introduction to the Physics of Highly Charged Ions. CRC Press. pp. 232–236. ISBN 978-0-7503-0481-8. OCLC 47150433

- ^ Watkins, Thayer. “Coherence in Stimulated Emission”. San José State University. 2008年1月12日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2007年12月23日閲覧。

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). オンライン版: (2006-) "valence".

- ^ Reusch, William (2007年7月16日). “Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry”. Michigan State University. 2007年10月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月11日閲覧。

- ^ “Covalent bonding – Single bonds”. chemguide (2000年). 2008年11月1日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年11月20日閲覧。

- ^ Husted, Robert (2003年12月11日). “Periodic Table of the Elements”. Los Alamos National Laboratory. 2008年1月10日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月11日閲覧。

- ^ Baum, Rudy (2003). “It's Elemental: The Periodic Table”. Chemical & Engineering News. オリジナルの6 April 2011時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Anderson, M. H.; Ensher, J. R.; Matthews, M. R.; Wieman, C. E.; Cornell, E. A. (1995-07-14). “Observation of Bose-Einstein Condensation in a Dilute Atomic Vapor” (英語). Science 269 (5221): 198–201. doi:10.1126/science.269.5221.198. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Goodstein, David L. (2002). States of Matter. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 436–438. ISBN 978-0-13-843557-8

- ^ Brazhkin, Vadim V. (2006). “Metastable phases, phase transformations, and phase diagrams in physics and chemistry”. Physics-Uspekhi 49 (7): 719–724. Bibcode: 2006PhyU...49..719B. doi:10.1070/PU2006v049n07ABEH006013.

- ^ Myers, Richard (2003). The Basics of Chemistry. Greenwood Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-313-31664-7. OCLC 50164580

- ^ Staff (2001年10月9日). “Bose–Einstein Condensate: A New Form of Matter”. National Institute of Standards and Technology. オリジナルの2008年1月3日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Colton, Imogen (1999年2月3日). “Super Atoms from Bose–Einstein Condensation”. The University of Melbourne. 2007年8月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年2月6日閲覧。

- ^ Georgescu, Iulia (2020-08). “25 years of BEC” (英語). Nature Reviews Physics 2 (8): 396–396. doi:10.1038/s42254-020-0211-7. ISSN 2522-5820.

- ^ Jacox, Marilyn (1997年11月). “Scanning Tunneling Microscope”. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2008年1月7日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月11日閲覧。

- ^ “The Nobel Prize in Physics 1986”. The Nobel Foundation. 2008年9月17日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月11日閲覧。 In particular, see the Nobel lecture by G. Binnig and H. Rohrer.

- ^ Jakubowski, N.; Moens, Luc; Vanhaecke, Frank (1998). “Sector field mass spectrometers in ICP-MS”. Spectrochimica Acta Part B: Atomic Spectroscopy 53 (13): 1739–1763. Bibcode: 1998AcSpe..53.1739J. doi:10.1016/S0584-8547(98)00222-5.

- ^ Müller, Erwin W.; Panitz, John A.; McLane, S. Brooks (1968). “The Atom-Probe Field Ion Microscope”. Review of Scientific Instruments 39 (1): 83–86. Bibcode: 1968RScI...39...83M. doi:10.1063/1.1683116.

- ^ Lochner, Jim (2007年4月30日). “What Do Spectra Tell Us?”. NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. 2008年1月16日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月3日閲覧。

- ^ Winter, Mark (2007年). “Helium”. WebElements. 2007年12月30日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月3日閲覧。

- ^ Hinshaw, Gary (2006年2月10日). “What is the Universe Made Of?”. NASA/WMAP. 2007年12月31日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月7日閲覧。

- ^ Choppin, Gregory R.; Liljenzin, Jan-Olov; Rydberg, Jan (2001). Radiochemistry and Nuclear Chemistry. Elsevier. p. 441. ISBN 978-0-7506-7463-8. OCLC 162592180

- ^ Davidsen, Arthur F. (1993). “Far-Ultraviolet Astronomy on the Astro-1 Space Shuttle Mission”. Science 259 (5093): 327–334. Bibcode: 1993Sci...259..327D. doi:10.1126/science.259.5093.327. PMID 17832344.

- ^ Lequeux, James (2005). The Interstellar Medium. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 978-3-540-21326-0. OCLC 133157789

- ^ Smith, Nigel (2000年1月6日). “The search for dark matter”. Physics World. 2008年2月16日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年2月14日閲覧。

- ^ Croswell, Ken (1991). “Boron, bumps and the Big Bang: Was matter spread evenly when the Universe began? Perhaps not; the clues lie in the creation of the lighter elements such as boron and beryllium”. New Scientist (1794): 42. オリジナルの7 February 2008時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Copi, Craig J.; Schramm, DN; Turner, MS (1995). “Big-Bang Nucleosynthesis and the Baryon Density of the Universe”. Science 267 (5195): 192–199. arXiv:astro-ph/9407006. Bibcode: 1995Sci...267..192C. doi:10.1126/science.7809624. PMID 7809624. オリジナルの14 August 2019時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Hinshaw, Gary (2005年12月15日). “Tests of the Big Bang: The Light Elements”. NASA/WMAP. 2008年1月17日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月13日閲覧。

- ^ Abbott, Brian (2007年5月30日). “Microwave (WMAP) All-Sky Survey”. Hayden Planetarium. 2013年2月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月13日閲覧。

- ^ Hoyle, F. (1946). “The synthesis of the elements from hydrogen”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 106 (5): 343–383. Bibcode: 1946MNRAS.106..343H. doi:10.1093/mnras/106.5.343.

- ^ Knauth, D.C.; Knauth, D.C.; Lambert, David L.; Crane, P. (2000). “Newly synthesized lithium in the interstellar medium”. Nature 405 (6787): 656–658. Bibcode: 2000Natur.405..656K. doi:10.1038/35015028. PMID 10864316.

- ^ Mashnik, Stepan G. (2000). "On Solar System and Cosmic Rays Nucleosynthesis and Spallation Processes". arXiv:astro-ph/0008382。

- ^ Kansas Geological Survey (2005年5月4日). “Age of the Earth”. University of Kansas. 2008年7月5日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月14日閲覧。

- ^ a b Manuel (2001). Origin of Elements in the Solar System, pp. 40–430, 511–519

- ^ Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). “The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved”. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 190 (1): 205–221. Bibcode: 2001GSLSP.190..205D. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14. オリジナルの11 November 2007時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Anderson, Don L. (2006年9月2日). “Helium: Fundamental models”. MantlePlumes.org. 2007年2月8日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月14日閲覧。

- ^ Pennicott, Katie (2001年5月10日). “Carbon clock could show the wrong time”. PhysicsWeb. オリジナルの2007年12月15日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Yarris, Lynn (2001年7月27日). “New Superheavy Elements 118 and 116 Discovered at Berkeley Lab”. Berkeley Lab. オリジナルの2008年1月9日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Diamond, H (1960). “Heavy Isotope Abundances in Mike Thermonuclear Device”. Physical Review 119 (6): 2000–2004. Bibcode: 1960PhRv..119.2000D. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.119.2000.

- ^ Poston, John W. Sr. (23 March 1998). “Do transuranic elements such as plutonium ever occur naturally?”. Scientific American. オリジナルの27 March 2015時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Keller, C. (1973). “Natural occurrence of lanthanides, actinides, and superheavy elements”. Chemiker Zeitung 97 (10): 522–530. OSTI 4353086.

- ^ Zaider, Marco; Rossi, Harald H. (2001). Radiation Science for Physicians and Public Health Workers. Springer. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-306-46403-4. OCLC 44110319

- ^ “Oklo Fossil Reactors”. Curtin University of Technology. 2007年12月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月15日閲覧。

- ^ Weisenberger, Drew. “How many atoms are there in the world?”. Jefferson Lab. 2007年10月22日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月16日閲覧。

- ^ Pidwirny, Michael. “Fundamentals of Physical Geography”. University of British Columbia Okanagan. 2008年1月21日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月16日閲覧。

- ^ Anderson, Don L. (2002). “The inner inner core of Earth”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99 (22): 13966–13968. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...9913966A. doi:10.1073/pnas.232565899. PMC 137819. PMID 12391308.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (1960). The Nature of the Chemical Bond. Cornell University Press. pp. 5–10. ISBN 978-0-8014-0333-0. OCLC 17518275

- ^ Anonymous (2 October 2001). “Second postcard from the island of stability”. CERN Courier. オリジナルの3 February 2008時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Karpov, A. V.; Zagrebaev, V. I.; Palenzuela, Y. M. et al. (2012). “Decay properties and stability of the heaviest elements”. International Journal of Modern Physics E 21 (2): 1250013-1–1250013-20. Bibcode: 2012IJMPE..2150013K. doi:10.1142/S0218301312500139. オリジナルの3 December 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。 2020年3月24日閲覧。.

- ^ “Superheavy Element 114 Confirmed: A Stepping Stone to the Island of Stability”. Berkeley Lab (2009年). 2019年7月20日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年3月24日閲覧。

- ^ Möller, P. (2016). “The limits of the nuclear chart set by fission and alpha decay”. EPJ Web of Conferences 131: 03002-1–03002-8. Bibcode: 2016EPJWC.13103002M. doi:10.1051/epjconf/201613103002. オリジナルの11 March 2020時点におけるアーカイブ。 2020年3月24日閲覧。.

- ^ Koppes, Steve (1999年3月1日). “Fermilab Physicists Find New Matter-Antimatter Asymmetry”. University of Chicago. オリジナルの2008年7月19日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Cromie, William J. (2001年8月16日). “A lifetime of trillionths of a second: Scientists explore antimatter”. Harvard University Gazette. 2006年9月3日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月14日閲覧。

- ^ Hijmans, Tom W. (2002). “Particle physics: Cold antihydrogen”. Nature 419 (6906): 439–440. Bibcode: 2002Natur.419..439H. doi:10.1038/419439a. PMID 12368837.

- ^ Staff (2002年10月30日). “Researchers 'look inside' antimatter”. BBC News. オリジナルの2007年2月22日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ Barrett, Roger (1990). “The Strange World of the Exotic Atom”. New Scientist (1728): 77–115. オリジナルの21 December 2007時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Indelicato, Paul (2004). “Exotic Atoms”. Physica Scripta T112 (1): 20–26. arXiv:physics/0409058. Bibcode: 2004PhST..112...20I. doi:10.1238/Physica.Topical.112a00020. オリジナルの4 November 2018時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Ripin, Barrett H. (1998年7月). “Recent Experiments on Exotic Atoms”. American Physical Society. 2012年7月23日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年2月15日閲覧。

原子と同じ種類の言葉

- >> 「原子」を含む用語の索引

- 原子のページへのリンク