ケレス (準惑星)

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2024/03/23 04:20 UTC 版)

自転と赤道傾斜

ケレスの自転周期(ケレスの太陽日)は9時間4分。赤道傾斜角は4°で、これは月や水星と同様に、ケレスの極地がコールドトラップとして機能し、時間の経過と共に水の氷が蓄積されると予想されている永久影を持つクレーターが存在出来るのに十分なほど低い傾斜である[89]。表面から放出された水分子の約0.14%がトラップに行き着くと予想されている[90]。

物理的特徴

ドーンによる探査で、ケレスの質量は9.39×1020 kgと測定されている[91]。この質量は、小惑星帯の推定全質量である3.0 ± 0.2×1021 kgの約3分の1を占めており[92]、月の質量の約1.3%に相当する。ケレスはほぼ球形の形状を維持するのに十分な大きさで[93]、ベスタとテティスの間の大きさを持つ。表面積はインドとアルゼンチンを合わせた面積とほぼ同じである[注 4]。2018年7月、NASAはケレスに見られる物理的特徴と地球上に存在する同様のものと比較した記事を公開した[47]。

表面

ケレスの表面組成はC型小惑星とほぼ一致しているが[11]、いくつか異なる点もある。ケレスの赤外線スペクトルのいたる部分には、水和した物質が存在していることを示す兆候が見られ、これは内部に大量の水が存在していることを示している。他に存在しうる表面成分として、鉄が豊富な粘土鉱物(クロンステダイト)および炭素質コンドライト隕石に一般的に存在する炭酸塩(ドロマイトと菱鉄鉱)が挙げられる[11]。炭酸塩と粘土鉱物の存在を示す兆候は他のC型小惑星のスペクトルでは見られない[11]。そのため、ケレスは時折G型小惑星として分類されることがある[94]。

ケレスの表面は比較的暖かく、1991年5月5日に太陽直下点での温度は235 K(-38 ℃、-36 ℉)と測定された[15]。この温度下では氷は不安定になる。表面の氷の昇華によって残された物質が、木星以前の惑星を公転する氷でできた衛星よりもケレスの表面を暗くさせているかもしれない。

ハッブル宇宙望遠鏡を用いた研究により、グラファイト、硫黄、二酸化硫黄がケレスの表面に存在することが明らかになっている。前者はケレスの古い表面が宇宙風化の影響を受けて生成されたとされている。後者の2つはケレスの条件下では揮発性で、すぐに放出されるかコールドトラップに行き着くと予想されているので、これらは地質的活動を最近伴った地域に関連しているとされている[95]。

ドーンによる探査以前の観測

ドーンによる探査以前は、ケレスの明白な表面の特徴はわずかしか検出されていなかった。1995年にハッブル宇宙望遠鏡が撮影した高解像度の紫外線画像で、表面に暗い地形があることが示された。この地形はケレスの発見者に因んで「ピアッツィ(Piazzi)」と呼ばれ[94]、クレーターであると考えられた。補償光学を用いてケック天文台によって撮影された、より高解像度の近赤外線全球画像から、ケレスの自転と共に移動するいくつかの明るい地形と暗い地形が示された[96][97]。そのうちの2つの暗い地形は形状が円形であったのでクレーターであると推測され、そのうち1つは中央に明るい地形を持つことが観測された。一方で、もう片方はピアッツィであると認識された[96][97]。2003年と2004年にハッブル宇宙望遠鏡が撮影したケレスの可視光線全球画像では、識別可能な地形が11個示されたが、それらの性質については未確定であった[13][98]。これらの地形のうちの1つは以前から観測されていたピアッツィに該当するとされている[13]。

こうした中での最後の観測では、ケレスの北極点がりゅう座の、赤経 19h 24m(291°)、赤緯+59°の方向を向いており、この結果から赤道傾斜角は3°であるとされた[13][93]。その後、ドーンによる探査で実際には北極点が赤経 19h 25m 40.3s(291.418°)、赤緯+66° 45′ 50″(りゅう座δ星から約1.5°)の方向を向いていることが確定し、その結果、赤道傾斜角は4°であると判明した[7]。

2014年1月には、ハーシェル宇宙望遠鏡の観測により2箇所からの水蒸気の噴出が確認された。量は1秒あたり6 kgであると推定されている。小惑星帯で彗星として活動するメインベルト彗星の存在は確認されていたが、水蒸気を観測したのは今回が初めてとなる。論文は1月23日にネイチャーに掲載された[99][100]。

ドーンによる探査

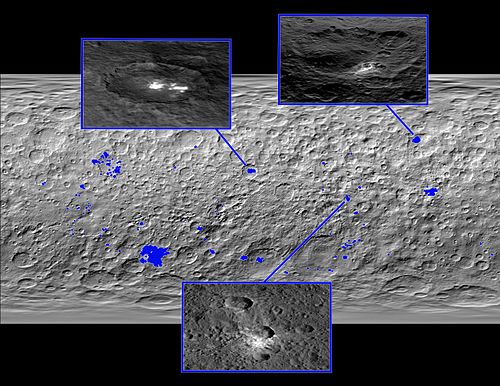

ドーンは、ケレスの表面がクレーターで覆われていることを明らかにした。しかし、ケレスには予想されていたよりも大型のクレーターは存在しておらず、これはおそらく過去の地質学的プロセスによるものとされている[101][102]。予想外にもケレスのクレーターの多くには、氷火山プロセスの影響で中央に窪み(central pit)があり、また多くは中央丘を持っている[103]。ケレスにある有名な山として、アフナ山(Ahuna Mons)がある。この地形は氷火山のように見え、クレーターがほとんど無いことから、最長でも数億年以内に形成されたことが示唆されている[104][105]。後のコンピューターシミュレーションでは、元々ケレスに存在していたが、粘性の低下によって認識できなくなった他の氷火山が存在する可能性が示されている[106]。ドーンはケレスにあるいくつかの「光点」を観測しており、そのうち最も明るい光点(スポット5)は、オッカトル(Occator)と呼ばれる直径80 kmのクレーターの中心に存在している[107]。2015年5月4日に撮影されたケレスの画像から、2番目に明るい光点が実際には、散在している10個もの明るい領域から成ることが明らかになった。これらの明るい地形はアルベド(反射率)が約40%にもなっており[108]、これは表面にある氷や塩といった太陽光を反射する物質によるものとされている[109][110]。最もよく知られている光点「スポット5」の上空には定期的に「もや」が現れる。これは、ある種のガス放出または昇華する氷が光点を形成したという仮説を支持するものとされている[110][111]。2016年3月、ドーンはオクソ(Oxo)クレーターで水分子が存在するという明確な証拠を発見した[112][113]。

2015年12月9日、NASAの科学者たちはケレスの光点は塩の種類、特に硫酸マグネシウム六水和物(MgSO4·H2O)を含む塩水の形態に関係していると報告した。また、その光点はアンモニアが豊富な粘土と関連していることも明らかになった[43]。これらの光点の近赤外線スペクトルが大量の炭酸ナトリウム(Na2CO3)、少量の塩化アンモニウム(NH4Cl)もしくは炭酸水素アンモニウム(NH4HCO3)の存在を示すものと一致することが2017年に報告されている[114][115]。これらの物質は、最近内部から表面に到達した塩水の結晶化に由来していることが示唆されている[44][45][46][116]。

2020年に欧米の科学者チームが行った研究発表ではケレスの観測を行ったドーンによる重力測定のデータから、直径約92kmの「オッカトル・クレーター(英:Occator Crater)」の地下およそ40kmの深さに今も約数百~1000kmの幅に渡って塩水が存在していることを断定した。 また、別の研究チームでは、これまで地球以外で観測された例がなかったハイドロハライトが存在することを発見した[117] [118]。

炭素

有機化合物(ソリン)がエルヌテト(Ernutet)と呼ばれるクレーターで検出されており[51][52]、またケレスの大部分は非常に炭素に富んでいて[119]、表面付近の全質量の約20%を占めている[120][121]。炭素含有量は地球上で分析されている炭素質コンドライト隕石よりも5倍以上多い[121]。表面の炭素は、岩石と水の相互作用でできた粘土のような生成物が混合されている証拠だとされている[120][121]。この化学組成は、ケレスが木星軌道よりも外側で、そして有機化学に有利な条件をもたらす水が存在する状況下でケレスが炭素に富む物質の降着によって形成された可能性を示している[120][121]。ケレスにこうした物質が見られるのは、生命にとって基本的な成分が宇宙全体に存在しているという証拠になる[119]。

スポット1(上段、周囲より温度が低い) スポット5(下段、周囲と温度は似通っている) |

内部構造

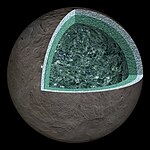

ケレスは、岩石質の核と氷のようなマントルと地殻で構成されていると考えられている。ドーンによる形状および重力場観測から、ケレスは偏微分[9][123] とアイソスタシー補償を伴う静水圧平衡の状態にあり、平均慣性モーメントは0.37とされた(この値はカリストの0.36と似ている)[124]。ケレスの質量のうち最大で25%を水が占めている可能性があり、その場合、ケレスには地球よりも多量の水が含まれていることになる[125]。

鉱物組成については深さ100 kmまでに対してのみ間接的に求める事が可能で、厚さ40 kmの表層は水、塩、水和鉱物の混合物になっている。その下には、少量の塩水を含んでいる可能性のある層があり、少なくとも鉱物組成を探知できる限界である深さ100 kmよりも深くにまで及んでいる。そのさらに下は粘土のような水和した岩が含まれるマントルになっていると考えられている。ケレスの内部で最も深いところには液体が含まれているのか、あるいは金属を豊富に含んでいる核が存在しているかを判断するのは現時点では不可能である[126]。モデリングでは、ケレスは岩石部分の部分的な分化により、金属から成る小さな核を持てることが示されている[127][128]。

ケレスの扁平率は、内部が岩石の核と氷のマントルとに分化している場合と一致しており[93]、この厚さ100 kmのマントル(ケレスの全質量の23~28 %、全体積の50%[129])には最大で、地球に存在する淡水の総量よりも多い2億 km3の水が含まれているとされている[130]。この結果は、2002年にケック望遠鏡で行われた観測と進化論的モデリングによって支持されている[28][96]。その表面と歴史の特性(形成時にかなり凝固点の低い成分を吸収できるほど日射量が弱かった太陽からの距離など)から、ケレスの内部に揮発性物質が含まれている可能性が指摘されており[96]、また、液体の水の層が氷の層の下に現在まで残っている可能性も示唆されている[28][29]。ある研究では、核と外層の密度はそれぞれ2.46~2.90 g/cm3と1.68~1.95 g/cm3、外層の厚さは約70~190 kmと推定されている。核からは部分的な脱水(氷の放出)が起きていると予想されており、水の氷と比較して外層の密度が大きいのは、ケイ酸塩と塩が含まれているのを反映している[124]。つまり、核、マントルそして地殻は全て氷もしくは岩石で構成されているが、その含有比率は異なるということになる。

別の研究では[131]、ケレスがコンドルールで構成されている核そして氷とミクロサイズの固体微粒子が混合している氷でできたマントルの2層から成る天体としてモデル化されている。表面での氷の昇華は厚さ20 mの水和粒子の堆積物を残すとされている。データと一致すると考えられる内部構成の予想範囲は大きく、75%がコンドル―ルで残る25%が微粒子からできている直径が380 kmの核と、75%の氷と25%の微粒子を含むマントルから成るとする核が最も大きくなる場合や、ほぼ完全に微粒子でできている直径が85 kmの核と、30%の氷と70%の微粒子のマントルでできているとする核が最も小さくなる場合まで様々なものがある。核が大きい場合では、塩水が存在出来るほど暖かくなっているはずだとされている。核が小さければ、110 kmより深い領域のマントルは液体のままになっているとされている。後者の場合、含まれている液体の2%が凍結していれば液体を表面に押し出すのに十分なほど圧縮することができ、氷火山を形成させるであろうと考えられている。これは、ケレスで平均で5,000万年ごとに1つの氷火山が生じたかもしれないという推測の比較になるかもしれない[132]。

大気

ケレスでは表面の水の氷からガス状の水蒸気が放出されている兆候が見られる[133][134][135]。

表面にある水の氷は、太陽から5 au未満の領域では不安定であり[136]、太陽からの放射に直接晒されると昇華してしまうと予想されている。氷はケレスの深層部から表面に移動することができるが、非常に短時間で放出されてしまう。そのため、結果として水の蒸発を検出することは困難である。ケレスの極地域からの水の放出は1990年代初頭に観測されていた可能性があるが、明確に実証はされていない。新しいクレーターの周囲もしくは地下層からの亀裂から放出される水を検出することは可能かもしれない[96]。国際紫外線天文衛星による紫外線観測では、ケレスの北極付近から統計的に有意な量の、紫外線の日射によって起きる水蒸気の解離の副産物である水酸化物イオンが検出されている[133]。

2014年初頭に、ハーシェル宇宙望遠鏡のデータから、ケレスの中緯度にいくつかの局所的(直径60 km以下)な水蒸気源があり、それぞれ1秒あたり1026個(3 kg)の水分子を放出していることが判明した[137][138][注 5]。ピアッツィ(北緯21°、経度123°)と「RegionA」(北緯23°、経度231°)と呼ばれる2つの潜在的な水蒸気源が、2002年のケック天文台による近赤外線の観測によって暗くなっている領域(RegionAの中央には明るい領域もある)として可視化されている。考え得る蒸気放出のメカニズムとして、表面積約0.6 km3の露呈している表面の氷の昇華、内部からの放射性崩壊による熱に起因する氷火山噴火[137]、上層にある氷の層の成長による地下の海の加圧が挙げられる[29]。ケレスが軌道上において太陽から離れた部分にいるとき、表面の氷の昇華だとその放出量は減少するが、内部から発せられた熱だとその放出率はケレスの軌道上の位置で変化することはない。限られている利用可能なデータでは、彗星のように氷の昇華に起因するというメカニズムの方により一貫性を示していた[137]。しかしその後のドーンによる調査で、活動中の地質的活動が少なくともそれらの一部に起因していることが強く示唆された[141][142]。

ドーンのガンマ線・中性子分光計(GRaND)を用いた研究で、ケレスが太陽風からの電子を規則的に加速させていることが明らかになった。この現象を引き起こしている原因としてはいくつかの可能性が考えられるが、最も受け入れられているのはこれらの電子が太陽風と水蒸気から成る弱い外圏との衝突によって加速されているという説である[143]。

2017年、ドーンはケレスが太陽活動に関連していると思われる一時的な大気を持っている事を確認した。太陽からの高エネルギーの粒子がケレスの露出した氷に衝突した際に、その氷が昇華することにより形成されるとされている[144]。

注釈

- ^ この画像は、ケレスの表面上空13,642 kmの軌道(Rotation Characterization 3 orbit)から撮影された。中央と中央右にあるのは、それぞれオクソ(Oxo)クレーターとハウラニ(Haulani)クレーターの中心にある光点である。アフナ山(Ahuna Mons)が画像の下部の右側に鈍い丘陵として見える。

- ^ その他の言語での名称は1つを除いてCeresもしくはCerereの変種を使用している。ロシア語は「Tserera」、ペルシア語は「Seres」、日本語は「ケレス(Keresu)」などとなっている。なお、英語読みをした場合はシリーズといった表記となる[62]。フランス語やスペイン語読みのセレスの名称で表記されることも多い。唯一の例外は中国語で、中国語では「穀神星 (gǔshénxīng)」と呼ばれる。

- ^ 1807年にKlaprothが、より語源に沿った「Cererium」という名称に変更しようとしたが、定着しなかった[68]。

- ^ オーストラリアの約40%、アメリカもしくはカナダの約3分の1、日本の約7倍、イギリスの約12倍に相当。

- ^ この放出率は、エンケラドゥス(ケレスより小さい)とヨーロッパ大陸全体(ケレスより大きい)の潮汐駆動プルームからの放出率と比べると小さく、それぞれの放出率は200 kg/s[139] と7,000 kg/s[140] である。

出典

- ^ a b Menzel, Donald H.; Pasachoff, Jay M. (1983). A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets (2nd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 391. ISBN 978-0-395-34835-2

- ^ APmag and AngSize generated with Horizons (Ephemeris: Observer Table: Quantities = 9,13,20,29) Archived 2011-10-05 at WebCite

- ^ a b Schmadel, Lutz (2003). Dictionary of minor planet names (5th ed.). Germany: Springer. p. 15. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t “1 Ceres”. ジェット推進研究所. 2018年11月14日閲覧。

- ^ “The MeanPlane (Invariable plane) of the Solar System passing through the barycenter” (2009年4月3日). 2009年5月14日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。 (produced with Solex 10 Archived 29 April 2009 at WebCite written by Aldo Vitagliano; see also en:Invariable plane)

- ^ a b “AstDyS-2 Ceres Synthetic Proper Orbital Elements”. University of Pisa. Department of Mathematics. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e Emily Lakdawalla. “05. Dawn Explores Ceres Results from the Survey Orbit”. 2015年9月5日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e 既知のパラメーターに基づいて計算

- ^ a b “DPS 2015: First reconnaissance of Ceres by Dawn”. Planetary.org (2015年11月12日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Chamberlain, Matthew A.; Sykes, Mark V.; Esquerdo, Gilbert A. (2007). “Ceres lightcurve analysis – Period determination”. Icarus 188 (2): 451–456. Bibcode: 2007Icar..188..451C. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.11.025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rivkin, A. S.; Volquardsen, E. L.; Clark, B. E. (2006). “The surface composition of Ceres:Discovery of carbonates and iron-rich clays” (PDF). Icarus 185 (2): 563–567. Bibcode: 2006Icar..185..563R. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.08.022.

- ^ “(1) Ceres = A899”. 小惑星センター. 2015年6月3日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g Li, Jian-Yang; McFadden, Lucy A.; Parker, Joel Wm. (2006). “Photometric analysis of 1 Ceres and surface mapping from HST observations”. Icarus 182 (1): 143–160. Bibcode: 2006Icar..182..143L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.12.012.

- ^ “Asteroid Ceres P_constants (PcK) SPICE kernel file”. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Saint-Pé, O.; Combes, N.; Rigaut F. (1993). “Ceres surface properties by high-resolution imaging from Earth”. Icarus 105 (2): 271–281. Bibcode: 1993Icar..105..271S. doi:10.1006/icar.1993.1125.

- ^ Angelo, Joseph A., Jr (2006). Encyclopedia of Space and Astronomy. New York: Infobase. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-8160-5330-8

- ^ 『オックスフォード天文学辞典』(初版第1刷)朝倉書店、135頁。ISBN 4-254-15017-2。

- ^ “小惑星日本語表記索引 : 1 - 50”. 日本惑星協会. 2019年3月9日閲覧。

- ^ “質問5-5)なぜ、火星と木星の間には大きな惑星ができなかったの?”. 国立天文台. 2023年2月19日閲覧。

- ^ 『天文学大事典』(初版第1版)地人書館、380頁。ISBN 978-4-8052-0787-1。

- ^ “惑星の定義とは?”. 国立天文台. 2023年2月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Ceres”. Dictionary.com. Random House, Inc.. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ JPL/NASA (2015年4月22日). “What is a Dwarf Planet?”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2022年1月19日閲覧。

- ^ Stankiewicz, Rick (2015年2月20日). “A visit to the asteroid belt”. Peterborough Examiner 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Williams, Matt (2015年8月23日). “What is the Asteroid Belt?”. Universe Today. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Dwarf Planet 1 Ceres Information”. TheSkyLive.com. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Ceres”. Solar System Exploration: NASA Science 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k McCord, T. B.; Sotin, C. (2005). “Ceres: Evolution and current state”. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 110 (E5): E05009. Bibcode: 2005JGRE..110.5009M. doi:10.1029/2004JE002244.

- ^ a b c O'Brien, D. P.; Travis, B. J.; Feldman, W. C.; Sykes, M. V.; Schenk, P. M.; Marchi, S.; Russell, C. T.; Raymond, C. A. (2015). "The Potential for Volcanism on Ceres due to Crustal Thickening and Pressurization of a Subsurface Ocean" (PDF). 46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. p. 2831.

- ^ “Water Detected on Dwarf Planet Ceres”. Science@NASA (NASA). (2014年1月22日) 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Landau, Elizabeth (2015年3月6日). “NASA Spacecraft Becomes First to Orbit a Dwarf Planet”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Dawn Spacecraft Begins Approach to Dwarf Planet Ceres”. NASA. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Rayman, Marc (2015年3月6日). “Dawn Journal: Ceres Orbit Insertion!”. The Planetary Society. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Plait, Phil (2015). “The Bright Spots of Ceres Spin Into View”. Slate 2019年3月31日閲覧。.

- ^ O'Neill, I. (2015年2月25日). “Ceres' Mystery Bright Dots May Have Volcanic Origin”. Discovery Inc.. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Landau, E. (2015年2月25日). “'Bright Spot' on Ceres Has Dimmer Companion”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2015年2月26日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Lakdawalla, E. (2015年2月26日). “At last, Ceres is a geological world”. The Planetary Society. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “LPSC 2015: First results from Dawn at Ceres: provisional place names and possible plumes”. The Planetary Society. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy (2015年3月3日). “Bright Spots on Ceres Likely Ice, Not Cryovolcanoes”. Universe Today. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Sundermier, Ali. “NASA just found an ice volcano on Ceres that's half the size of Everest”. ScienceAlert. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Ruesch, O.; Platz, T.; Schenk, P.; McFadden, L. A.; Castillo-Rogez, J. C.; Quick, L. C.; Byrne, S.; Preusker, F. et al. (2016). “Cryovolcanism on Ceres”. Science 353 (6303): aaf4286. Bibcode: 2016Sci...353.4286R. doi:10.1126/science.aaf4286. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 27701087.

- ^ “Ceres RC3 Animation”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2015年5月11日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Landau, Elizabeth (2015年12月9日). “New Clues to Ceres' Bright Spots and Origins”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Landau, Elizabeth; Greicius, Tony (2016年6月29日). “Recent Hydrothermal Activity May Explain Ceres' Brightest Area” 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Lewin, Sarah (2016年6月29日). “Mistaken Identity: Ceres Mysterious Bright Spots Aren't Epsom Salt After All”. Space.com 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b De Sanctis, M. C. et al. (2016). “Bright carbonate deposits as evidence of aqueous alteration on (1) Ceres”. Nature 536 (7614): 54–57. Bibcode: 2016Natur.536...54D. doi:10.1038/nature18290. PMID 27362221.

- ^ a b Landau, Elizabeth (2018年7月24日). “What Looks Like Ceres on Earth?”. NASA. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Rayman, Marc (2018年6月13日). “Dawn - Mission Status”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen (2018年6月15日). “Dawn spacecraft flying low over Ceres”. SpaceFlightNow.com. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Dawn data from Ceres publicly released: Finally, color global portraits!”. The Planetary Society. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Dawn discovers evidence for organic material on Ceres (Update)”. Phys.org (2017年2月16日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Jean-Philippe Combe; Sandeep Singh; Christopher T. Russell (2018). “The surface composition of Ceres’ Ezinu quadrangle analyzed by the Dawn mission”. Icarus. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2017.12.039.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hoskin, Michael (1992年6月26日). “Bode's Law and the Discovery of Ceres”. Observatorio Astronomico di Palermo "Giuseppe S. Vaiana". 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Hogg, Helen Sawyer (1948). “The Titius-Bode Law and the Discovery of Ceres”. Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 242: 241–246. Bibcode: 1948JRASC..42..241S.

- ^ Hoskin, Michael (1999). The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy. Cambridge University press. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-0-521-57600-0

- ^ Landau, Elizabeth (2016年1月26日). “Ceres: Keeping Well-Guarded Secrets for 215 Years”. NASA. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g Forbes, Eric G. (1971). “Gauss and the Discovery of Ceres”. Journal for the History of Astronomy 2 (3): 195–199. Bibcode: 1971JHA.....2..195F. doi:10.1177/002182867100200305.

- ^ Cunningham, Clifford J. (2001). The first asteroid: Ceres, 1801–2001. Star Lab Press. ISBN 978-0-9708162-1-4

- ^ Hilton, James L.. “Asteroid Masses and Densities” (PDF). U.S. Naval Observatory. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Hughes, D. W. (1994). “The Historical Unravelling of the Diameters of the First Four Asteroids”. R.A.S. Quarterly Journal 35 (3): 331. Bibcode: 1994QJRAS..35..331H. (Page 335)

- ^ Foderà Serio, G.; Manara, A.; Sicoli, P. (2002). “Giuseppe Piazzi and the Discovery of Ceres”. In W. F. Bottke Jr.; A. Cellino; P. Paolicchi et al.. Asteroids III. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. pp. 17–24

- ^ 佐藤勲 (2013年6月29日). “小惑星名の発音調査”. 第9回小惑星ライトカーブ研究会. Minor Planet at 366. 2015年1月3日閲覧。

- ^ Rüpke, Jörg (2011). A Companion to Roman Religion. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-1-4443-4131-7

- ^ Simpson, D. P. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5th ed.). London: Cassell Ltd. p. 883. ISBN 978-0-304-52257-6

- ^ Unicode value U+26B3

- ^ Gould, B. A. (1852). “On the symbolic notation of the asteroids”. Astronomical Journal 2 (34): 80. Bibcode: 1852AJ......2...80G. doi:10.1086/100212.

- ^ “Cerium: historical information”. Adaptive Optics. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ "Cerium". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (要購読、またはイギリス公立図書館への会員加入。)

- ^ “Amalgamator Features 2003: 200 Years Ago” (2003年10月30日). 2006年2月7日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Hilton, James L. (2001年9月17日). “When Did the Asteroids Become Minor Planets?”. 2010年1月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Herschel, William (1802). “Observations on the two lately discovered celestial Bodies”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 92: 213–232. Bibcode: 1802RSPT...92..213H. doi:10.1098/rstl.1802.0010. JSTOR 107120.

- ^ Battersby, Stephen (2006年8月16日). “Planet debate: Proposed new definitions”. New Scientist. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Connor, Steve (2006年8月16日). “Solar system to welcome three new planets”. NZ Herald 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Gingerich, Owen et al. (2006年8月16日). “The IAU draft definition of "Planet" and "Plutons"”. International Astronomical Union. 2011年10月5日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “The IAU Draft Definition of Planets And Plutons”. SpaceDaily (2006年8月16日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Gaherty, Geoff (2011年8月5日). “How to Spot Giant Asteroid Vesta in Night Sky This Week”. Space.com. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Question and answers 2”. International Astronomical Union. 2011年10月5日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Spahr, T. B. (2006年9月7日). “MPEC 2006-R19: EDITORIAL NOTICE”. Minor Planet Center. 2019年3月31日閲覧。 “the numbering of "dwarf planets" does not preclude their having dual designations in possible separate catalogues of such bodies.”

- ^ Lang, Kenneth (2011). The Cambridge Guide to the Solar System. Cambridge University Press. pp. 372, 442. ISBN 9781139494175

- ^ NASA/JPL, Dawn Views Vesta, 2 August 2011 Archived 2011-10-05 at WebCite ("Dawn will orbit two of the largest asteroids in the Main Belt").

- ^ de Pater; Lissauer (2010). Planetary Sciences (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85371-2

- ^ Mann, Ingrid; Nakamura, Akiko; Mukai, Tadashi (2009). Small bodies in planetary systems. Lecture Notes in Physics. 758. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-76934-7

- ^ a b Cellino, A. et al. (2002). “Spectroscopic Properties of Asteroid Families”. Asteroids III. University of Arizona Press. pp. 633–643 (Table on p. 636). Bibcode: 2002aste.book..633C

- ^ Kelley, M. S.; Gaffey, M. J. (1996). “A Genetic Study of the Ceres (Williams #67) Asteroid Family”. Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society 28: 1097. Bibcode: 1996DPS....28.1009K.

- ^ Kovačević, A. B. (2011). “Determination of the mass of Ceres based on the most gravitationally efficient close encounters”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 419 (3): 2725–2736. arXiv:1109.6455. Bibcode: 2012MNRAS.419.2725K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19919.x.

- ^ Christou, A. A. (2000). “Co-orbital objects in the main asteroid belt”. Astronomy and Astrophysics 356: L71–L74. Bibcode: 2000A&A...356L..71C.

- ^ Christou, A. A.; Wiegert, P. (2012). “A population of Main Belt Asteroids co-orbiting with Ceres and Vesta”. Icarus 217 (1): 27–42. arXiv:1110.4810. Bibcode: 2012Icar..217...27C. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2011.10.016. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ “Solex numbers generated by Solex”. 2009年4月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Williams, David R. (2004年). “Asteroid Fact Sheet”. 2010年1月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Schorghofer, N.; Mazarico, E.; Platz, T.; Preusker, F.; Schröder, S. E.; Raymond, C. A.; Russell, C. T. (6 July 2016). “The permanently shadowed regions of dwarf planet Ceres”. Geophysical Research Letters 43 (13): 6783–6789. Bibcode: 2016GeoRL..43.6783S. doi:10.1002/2016GL069368.

- ^ Rayman, Marc D. (2015年5月28日). “Dawn Journal, May 28, 2015”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2015年5月30日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Pitjeva, E. V. (2005). “High-Precision Ephemerides of Planets—EPM and Determination of Some Astronomical Constants”. Solar System Research 39 (3): 176–186. Bibcode: 2005SoSyR..39..176P. doi:10.1007/s11208-005-0033-2.

- ^ a b c Thomas, P. C.; Parker, J. Wm.; McFadden, L. A. et al. (2005). “Differentiation of the asteroid Ceres as revealed by its shape”. Nature 437 (7056): 224–226. Bibcode: 2005Natur.437..224T. doi:10.1038/nature03938. PMID 16148926.

- ^ a b c Parker, J. W.; Stern, Alan S.; Thomas Peter C. et al. (2002). “Analysis of the first disk-resolved images of Ceres from ultraviolet observations with the Hubble Space Telescope”. The Astronomical Journal 123 (1): 549–557. arXiv:astro-ph/0110258. Bibcode: 2002AJ....123..549P. doi:10.1086/338093.

- ^ “Sulfur, Sulfur Dioxide, Graphitized Carbon Observed on Ceres”. spaceref.com (2016年9月3日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e Benoit, Carry et al. (2007). “Near-Infrared Mapping and Physical Properties of the Dwarf-Planet Ceres” (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics 478 (1): 235–244. arXiv:0711.1152. Bibcode: 2008A&A...478..235C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078166. オリジナルの2008-05-30時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ a b c “Keck Adaptive Optics Images the Dwarf Planet Ceres”. Adaptive Optics (2006年10月11日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Largest Asteroid May Be 'Mini Planet' with Water Ice”. HubbleSite. (2005年9月7日) 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Localized sources of water vapour on the dwarf planet (1) Ceres”. nature (2014年1月23日). 2015年6月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Herschel Telescope Detects Water on Dwarf Planet”. NASA. (2014年1月22日) 2014年2月11日閲覧。

- ^ Arizona State University (2016年7月26日). “The case of the missing craters”. ScienceDaily. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Marchi, S.; Ermakov, A. I.; Raymond, C. A.; Fu, R. R.; O’Brien, D. P.; Bland, M. T.; Ammannito, E.; De Sanctis, M. C. et al. (2016). “The missing large impact craters on Ceres”. Nature Communications 7: 12257. Bibcode: 2016NatCo...712257M. doi:10.1038/ncomms12257. PMC 4963536. PMID 27459197.

- ^ “News – Ceres Spots Continue to Mystify in Latest Dawn Images”. NASA/JPL. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Steigerwald, Bill (2016年9月2日). “NASA Discovers "Lonely Mountain" on Ceres Likely a Salty-Mud Cryovolcano”. NASA. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Ceres: The tiny world where volcanoes erupt ice”. SpaceDaily. (2016年9月5日) 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Sori, Michael M.; Byrne, Shane; Bland, Michael T.; Bramson, Ali M.; Ermakov, Anton I.; Hamilton, Christopher W.; Otto, Katharina A.; Ruesch, Ottaviano et al. (2017). “The vanishing cryovolcanoes of Ceres”. Geophysical Research Letters 44 (3): 1243–1250. Bibcode: 2017GeoRL..44.1243S. doi:10.1002/2016GL072319. hdl:10150/623032.

- ^ “USGS: Ceres nomenclature” (PDF). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rayman, Marc (8 April 2015). Now Appearing At a Dwarf Planet Near You: NASA's Dawn Mission to the Asteroid Belt (Speech). Silicon Valley Astronomy Lectures. Foothill College, Los Altos, CA. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Landau, Elizabeth (2015年5月11日). “Ceres Animation Showcases Bright Spots”. NASA. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Witze, Alexandra (2015年7月21日). “Mystery haze appears above Ceres’s bright spots”. Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.18032 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rivkin, Andrew (2015年7月21日). “Dawn at Ceres: A haze in Occator crater?”. The Planetary Society. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Dawn Mission – News – Detail”. NASA. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Redd, Nola Taylor. “Water Ice on Ceres Boosts Hopes for Buried Ocean”. Scientific American. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Preferential formation of sodium salts from frozen sodium-ammonium-chloride-carbonate brines – Implications for Ceres’ bright spots. Tuan H. Vu, Robert Hodyss, Paul V. Johnson, Mathieu Choukroun. Planetary and Space Science, Volume 141, July 2017, Pages 73-77

- ^ Thomas B. McCord; Francesca Zambon (2018). “The surface composition of Ceres from the Dawn mission”. Icarus. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2018.03.004.

- ^ De Sanctis, M. C. et al. (2016). “Bright carbonate deposits as evidence of aqueous alteration on (1) Ceres”. Nature 536 (7614): 54-57. Bibcode: 2016Natur.536...54D. doi:10.1038/nature18290. PMID 27362221.

- ^ “準惑星ケレスは「海洋天体」 研究”. AFPBB News. 令和2年8月13日閲覧。

- ^ “準惑星ケレス、溜まった塩水が地下から湧き上がっている可能性”. 令和2年8月13日閲覧。

- ^ a b Anderson, Paul Scott (2018年12月27日). “What does Ceres' carbon mean?”. Earth and Sky. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d “Team finds evidence for carbon-rich surface on Ceres”. Southwest Research Institute. Phys.org (2018年). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e Marchi, S.; Raponi, A.; Prettyman, T. H.; De Sanctis, M. C.; Castillo-Rogez, J.; Raymond, C. A.; Ammannito, E.; Bowling, T. et al. (2018). “An aqueously altered carbon-rich Ceres”. Nature Astronomy 3 (2): 140–145. Bibcode: 2018NatAs.tmp..181M. doi:10.1038/s41550-018-0656-0.

- ^ “PIA20348: Ahuna Mons Seen from LAMO”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2016年3月7日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “What's Inside Ceres? New Findings from Gravity Data”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Park, R. S.; Konopliv, A. S.; Bills, B. G.; Rambaux, N.; Castillo-Rogez, J. C.; Raymond, C. A.; Vaughan, A. T.; Ermakov, A. I. et al. (2016). “A partially differentiated interior for (1) Ceres deduced from its gravity field and shape”. Nature 537 (7621): 515–517. Bibcode: 2016Natur.537..515P. doi:10.1038/nature18955. PMID 27487219.

- ^ “Ceres In Depth”. NASA. 2019年5月31日閲覧。

- ^ “PIA22660: Ceres' Internal Structure (Artist's Concept)”. Photojournal. Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2019年5月31日). 2019年4月22日閲覧。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

この記述には、アメリカ合衆国内でパブリックドメインとなっている記述を含む。

- ^ Neumann, W.; Breuer, D.; Spohn, T. (2015). “Modelling the internal structure of Ceres: Coupling of accretion with compaction by creep and implications for the water-rock differentiation” (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics 584: A117. Bibcode: 2015A&A...584A.117N. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527083.

- ^ a b Bhatia, G. K.; Sahijpal, S. (2017). “Thermal evolution of trans-Neptunian objects, icy satellites, and minor icy planets in the early solar syste”. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 52 (12): 2470–2490. Bibcode: 2017M&PS...52.2470B. doi:10.1111/maps.12952.

- ^ 0.72–0.77 anhydrous rock by mass, per McKinnon, William B. (2008). “On the Possibility of Large KBOs Being Injected Into the Outer Asteroid Belt”. American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting No. 40 40: 464. Bibcode: 2008DPS....40.3803M. #38.03.

- ^ Carey, Bjorn (2005年9月7日). “Largest Asteroid Might Contain More Fresh Water than Earth”. Space.com 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ M. Neveu and S. J. Desch (2016) 'Geochemistry, thermal evolution, and cryovolanism on Ceres with a muddy ice mantle'. 47th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference

- ^ “Ceres takes life an ice volcano at a time”. University of Arizona (2018年9月17日). 2019年5月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b A'Hearn, Michael F.; Feldman, Paul D. (1992). “Water vaporization on Ceres”. Icarus 98 (1): 54–60. Bibcode: 1992Icar...98...54A. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(92)90206-M.

- ^ “Ceres: The Smallest and Closest Dwarf Planet”. Space.com (2018年5月23日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Dwarf Planet Ceres, Artist's Impression”. NASA (2014年1月22日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Jewitt, D; Chizmadia, L.; Grimm, R.; Prialnik, D (2007). “Water in the Small Bodies of the Solar System”. In Reipurth, B.; Jewitt, D.; Keil, K.. Protostars and Planets V. University of Arizona Press. pp. 863–878. ISBN 978-0-8165-2654-3

- ^ a b c Küppers, M.; O'Rourke, L.; Bockelée-Morvan, D.; Zakharov, V.; Lee, S.; Von Allmen, P.; Carry, B.; Teyssier, D. et al. (2014). “Localized sources of water vapour on the dwarf planet (1) Ceres”. Nature 505 (7484): 525–527. Bibcode: 2014Natur.505..525K. doi:10.1038/nature12918. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 24451541.

- ^ Campins, H.; Comfort, C. M. (2014). “Solar system: Evaporating asteroid”. Nature 505 (7484): 487–488. Bibcode: 2014Natur.505..487C. doi:10.1038/505487a. PMID 24451536.

- ^ Hansen, C. J.; Esposito, L.; Stewart, A. I.; Colwell, J.; Hendrix, A.; Pryor, W.; Shemansky, D.; West, R. (2006). “Enceladus' Water Vapor Plume”. Science 311 (5766): 1422–1425. Bibcode: 2006Sci...311.1422H. doi:10.1126/science.1121254. PMID 16527971.

- ^ Roth, L.; Saur, J.; Retherford, K. D.; Strobel, D. F.; Feldman, P. D.; McGrath, M. A.; Nimmo, F. (2013). “Transient Water Vapor at Europa's South Pole” (PDF). Science 343 (6167): 171–174. Bibcode: 2014Sci...343..171R. doi:10.1126/science.1247051. PMID 24336567.

- ^ Arizona State University (2016年9月1日). “Ceres: The tiny world where volcanoes erupt ice”. Science Daily. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Hiesinger, H.; Marchi, S.; Schmedemann, N.; Schenk, P.; Pasckert, J. H.; Neesemann, A.; OBrien, D. P.; Kneissl, T. et al. (2016). “Cratering on Ceres: Implications for its crust and evolution”. Science 353 (6303): aaf4759. Bibcode: 2016Sci...353.4759H. doi:10.1126/science.aaf4759. PMID 27701089.

- ^ “Ceres' geological activity, ice revealed in new research”. Science Daily. Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2016年9月1日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Confirmed: Ceres Has a Transient Atmosphere - Universe Today”. Universe Today. (2017年4月6日) 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Petit, Jean-Marc; Morbidelli, Alessandro (2001). “The Primordial Excitation and Clearing of the Asteroid Belt” (PDF). Icarus 153 (2): 338–347. Bibcode: 2001Icar..153..338P. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6702.

- ^ Approximately a 10% chance of the asteroid belt acquiring a Ceres-mass KBO. McKinnon, William B. (2008). “On the Possibility of Large KBOs Being Injected Into the Outer Asteroid Belt”. American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting No. 40 40: 464. Bibcode: 2008DPS....40.3803M. #38.03.

- ^ Greicius, Tony (2016年6月29日). “Recent Hydrothermal Activity May Explain Ceres' Brightest Area”. NASA. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Castillo-Rogez, J. C.; McCord, T. B.; Davis, A. G. (2007). “Ceres: evolution and present state” (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVIII: 2006–2007.

- ^ Wall, Mike (2016年9月2日). “NASA's Dawn Mission Spies Ice Volcanoes on Ceres”. Scientific American. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Wall, Mike (2014年7月27日). “Strange Bright Spots on Ceres Create Mini-Atmosphere on Dwarf Planet”. Space.com 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Catling, David C. (2013). Astrobiology: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-19-958645-5

- ^ Castillo-Rogez, J. C.; Conrad, P. G. (2010). Habitability Potential of Ceres, a Warm Icy Body in the Asteroid Belt (PDF). LPI Conference 2010. Lunar and Planetary Institute.

- ^ Hand, Eric (2015). “Dawn probe to look for a habitable ocean on Ceres”. Science 347 (6224): 813–814. Bibcode: 2015Sci...347..813H. doi:10.1126/science.347.6224.813. PMID 25700494.

- ^ “SPHERE Maps the Surface of Ceres”. European Southern Observatory. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Martinez, Patrick (1994). The Observer's Guide to Astronomy. Cambridge University Press. p. 298

- ^ Millis, L. R.; Wasserman, L. H.; Franz, O. Z. et al. (1987). “The size, shape, density, and albedo of Ceres from its occultation of BD+8°471”. Icarus 72 (3): 507–518. Bibcode: 1987Icar...72..507M. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(87)90048-0. hdl:2060/19860021993.

- ^ a b “Asteroid Occultation Updates”. Asteroidoccultation.com (2012年12月22日). 2012年7月12日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Water Detected on Dwarf Planet Ceres”. Science.nasa.gov. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Ulivi, Paolo; Harland, David (2008). Robotic Exploration of the Solar System: Hiatus and Renewal, 1983–1996. Springer Praxis Books in Space Exploration. Springer. pp. 117–125. ISBN 978-0-387-78904-0

- ^ Russell, C. T.; Capaccioni, F.; Coradini, A. et al. (2007). “Dawn Mission to Vesta and Ceres” (PDF). Earth, Moon, and Planets 101 (1–2): 65–91. Bibcode: 2007EM&P..101...65R. doi:10.1007/s11038-007-9151-9.

- ^ “NASA's Dawn Captures First Image of Nearing Asteroid”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2011年5月11日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rayman, Marc (2014年12月1日). “Dawn Journal: Looking Ahead at Ceres”. Planetary Society. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “探査機「ドーン」、準惑星ケレスに到着”. AstroArts (2015年3月6日). 2015年3月9日閲覧。

- ^ Schenk, P. (2015年1月15日). “Year of the 'Dwarves': Ceres and Pluto Get Their Due”. Planetary Society. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rayman, Marc (2014年3月3日). “Dawn Journal: Maneuvering Around Ceres”. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rayman, Marc (2014年4月30日). “Dawn Journal: Explaining Orbit Insertion”. Planetary Society. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rayman, Marc (2014年6月30日). “Dawn Journal: HAMO at Ceres”. Planetary Society. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rayman, Marc (2014年8月31日). “Dawn Journal: From HAMO to LAMO and Beyond”. Planetary Society. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Russel, C. T.; Capaccioni, F.; Coradini, A. et al. (2006). “Dawn Discovery mission to Vesta and Ceres: Present status”. Advances in Space Research 38 (9): 2043–2048. arXiv:1509.05683. Bibcode: 2006AdSpR..38.2043R. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2004.12.041.

- ^ Rayman, Marc (2015年1月30日). “Dawn Journal: Closing in on Ceres”. Planetary Society. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Dawn Operating Normally After Safe Mode Triggered”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2014年9月16日). 2014年12月25日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ China's Deep-space Exploration to 2030 by Zou Yongliao Li Wei Ouyang Ziyuan Key Laboratory of Lunar and Deep Space Exploration, National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing

- ^ Landau, Elizabeth (2015年7月28日). “New Names and Insights at Ceres”. NASA. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Staff (2015年7月17日). “First 17 Names Approved for Features on Ceres”. United States Geological Survey. 2015年8月6日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Dwarf planet Ceres gets place names、Andrew R. Brown、EarthSky(2015年3月24日)、2015年7月25日閲覧

- ^ Krummheuer, B. (2015年2月25日). “Dawn: Two new glimpses of dwarf planet Ceres”. Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rayman, Marc (2015年3月31日). “Dawn Journal March 31 [2015]”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2015年9月5日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rayman, Marc (2015年7月30日). “Dawn Journal: Descent to HAMO”. Planetary Society. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Dawn Mission Status Updates”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2015年10月16日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “PIA21221: Dawn XMO2 Image 1”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2016年11月7日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rayman, Marc D. (2016年11月28日). “Dawn Journal”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b Rayman, Marc (2017年). “2017 Mission Status Updates”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rayman, Marc (2018年5月25日). “Dawn Journal: Getting Elliptical”. Planetary Society. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rayman, Marc (2018年3月20日). “Dear Vernal Dawnquinoxes”. NASA. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rayman, Marc (2018年). “2018 Mission Status Archive”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Kornfeld, Laurel (2018年6月2日). “Dawn will enter lowest ever orbit around Ceres”. Spaceflight Insider 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Rayman, Marc (2018年4月29日). “Dear Isaac Newdawn, Charles Dawnwin, Albert Einsdawn and all other science enthusiasts”. NASA. 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “Fly Over Ceres in New Video”. NASA (2015年6月8日). 2019年3月31日閲覧。

- ケレス (準惑星)のページへのリンク