熱水噴出孔

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2024/05/24 02:19 UTC 版)

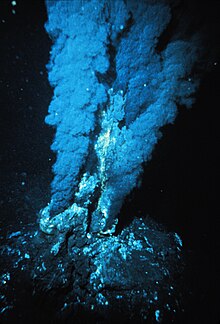

熱水噴出孔の大半は、火山活動が活発な海域(発散的プレート境界、海盆、ホットスポット)から発見されている[1]。吹き出す熱水は数百度にも達する事があり、溶存成分として重金属や硫化水素を豊富に含むものも知られている。海底から噴出する熱水に含まれる金属などが析出・沈殿してチムニーと呼ばれる構造物ができる場合がある。熱水の溶存成分によってはチムニーから黒色や白色の煙が吹き出しているように見えるため、一部の熱水噴出孔は「ブラックスモーカー」や「ホワイトスモーカー」と呼称される場合もある。また、熱水噴出孔の作用によって形成された岩石および鉱石堆積物を熱水堆積物と呼ぶ。

深海の大部分と比べて、熱水噴出孔周辺では生物活動が活発であり、噴出する熱水中に溶解した各種化学物質に依存した複雑な生態系が成立している。有機物合成を行う細菌や古細菌が食物連鎖の最底辺を支える他、化学合成細菌と共生したり環境中の化学合成細菌のバイオフィルムなどを摂食するジャイアントチューブワーム・二枚貝・エビなどの大型生物もみられる。

地球外では、木星の衛星エウロパや土星の衛星エンケラドスにおいても熱水活動が活発であり、熱水噴出孔が存在するとみられている[2][3]。また、古代には火星面にも存在したと考えられている[1][4]。

物理的特性

深海熱水噴出孔は通常、東太平洋海嶺や中部大西洋海嶺などの、2つの構造プレートが分岐し、マントルプリュームが上昇して新しい地殻が形成される場所で見られる[5]。熱水噴出孔から出てくる水は、主に近辺の火山層中の断層や多孔質堆積物を通じて染み込み火山性の地熱構造で熱せられた海水と、湧昇するマグマから放出されたマグマ水、の2種から構成される[1]。一方で、噴気孔や間欠泉といった陸上の熱水システムにおいては、循環する水の大部分は地表から熱水システムに浸透した天水(雨水)と地下水であり、一部で変成水やマグマに由来するマグマ水、堆積層中で塩類を溶解した塩水なども含まれる。その割合は、それぞれの場所によって異なる。

一般的に深海の海水温は約2 °C (36 °F)程度であるのに対し、熱水噴出孔周囲の水温は60 °C (140 °F)になり[6]、最高で464 °C (867 °F) にも達する例が知られている[7][8]。これは、深海ではその水深のため静水圧が高く、高温であっても水は気体にならずに液体の形で存在しているためである。純水の臨界点の温度は375 °C (707 °F) であり、圧力は218気圧である。さらに、純粋ではなく塩分を含む水の場合、高温と高圧の臨界点はさらに上昇する。海水(重量比で3.2%のNaClを含む)の臨界点は、298.5大気圧下で407 °C (765 °F)であり[9][10]、これは深さ2,960メートル (9,710 ft)の水圧環境下に対応する。したがって、この塩分濃度と深さの場合、熱水の温度が407 °C (765 °F)を超えると超臨界水となる。さらに、地殻の相分離のために、熱水噴出孔から吹き出す流体中の塩分は、時おり大きく変動することが知られている[11]。同一の圧力条件下において、塩分濃度の低い液体の臨界点温度は、海水よりも低く、純水よりも高くなる。たとえば、280.5大気圧下で2.24%のNaCl溶液の臨界点温度は400 °C (752 °F)である。したがって、熱水噴出孔の最も高温の部分の水は、気体と液体の間の物理的性質を持つ、いわゆる超臨界流体である可能性がある[12][13]。実際にいくつかの噴出孔において、超臨界状態が観察されている。しかしながら、熱水循環、鉱物堆積物形成、地球化学フラックス、そして生物活性の点で、この超臨界がどのような影響を与えるのかは、まだよく判明していない。

チムニーの成長と熱水の例

熱水噴出孔によってはチムニー(煙突)とよばれる円柱状の構造物を形成することがある。超高温の熱水に溶解している鉱物が0°Cに近い海水と接触すると、接触面で化学反応が進み生成物が析出・沈殿して、このようなチムニーができる。チムニー形成の初期段階は、鉱物の無水石膏の堆積から始まる。次に、銅や鉄、亜鉛などの硫化物が海水の境界面で析出してチムニーの隙間に沈殿し、時間の経過とともにチムニーの多孔性が低下する。今までの研究から、一日あたり30センチメートル (1 ft)程度も成長したチムニーが記録されている[14]。チムニーの例としては、オレゴン州の沖合にある高さ40mで折れてしまった、通称『ゴジラ』と呼ばれるものが知られる。チムニーのなかには高さ60mに達するものもある[15]。2007年4月のフィジー沿岸沖の深海ベントの調査では、これらのベントが溶存鉄の重要な供給源であることが判明している[16]。

チムニー構造で黒色の熱水を噴出するものは、黒い煙を放出する煙突のように見えるため、ブラックスモーカーと呼ばれる。ブラックスモーカーは通常、海底帯(水深2,500-3,000 m)でよく見られるが、より浅層や深層でも発見されている[1]。ブラックスモーカーは通常、地殻から熱水に溶け混んだ高レベルの硫黄含有ミネラルや硫化物を含む粒子を放出しており、水は400℃以上の高温に達することもある。地球の地殻の下から過熱された熱水が海底を通過する際に幅数百メートルに広がり、近辺で複数のブラックスモーカーが形成される[1]。冷たい海の水と接触すると、多くのミネラルが沈殿し、各孔の周りに黒い煙突のような構造(チムニー)を形成する。この堆積した金属硫化物は、ゆくゆくは塊状の硫化鉱床になる可能性がある。大西洋中央海嶺のアゾレス諸島の一部のブラックスモーカーは、24,000μMの鉄を含む熱水を放出するレインボーベントフィールドなど、金属含有量が非常に豊富なことが知られている[17]。

ブラックスモーカーは、RISEプロジェクト中にスクリップス海洋研究所の研究者によって、1979年に東太平洋海嶺から発見され、ウッズホール海洋研究所の深海潜水艇ALVIN号を用いて観測された[18]。現在、ブラックスモーカーは大西洋と太平洋に、平均2,100mの深度で存在することが知られている。最も北に位置するブラックスモーカーは、グリーンランドとノルウェーの間の大西洋中央海嶺の北緯73度の位置から、ベルゲン大学の研究者によって2008年に発見された、「ロキの城(Loki's Castle)」と名付けられたフィールドの5本のチムニーからなるクラスターである[19]。これらのブラックスモーカーは、地殻変動力が少ない安定した地殻領域にあり、熱水噴出孔のフィールドとしてはあまり一般的ではないため、興味がもたれている[20]。また、他の世界で最も有名なブラックスモーカーの一つはケイマントラフにあり、5,000 mの海面下に存在する[21]。

一方で、ホワイトスモーカーと呼ばれるチムニーからは、バリウム、カルシウム、シリコンなどの明るい色のミネラルが放出される。これらのベントは、おそらく熱源から一般に離れているため、プルームが低温になる傾向がある[1]。

ブラックとホワイトのチムニーは、同じ熱水フィールドで共存する可能性があり、それぞれ一般的に、熱源に対して近位か遠位かで分かれる。また、マグマが冷えて結晶化が進むことにより熱源から次第に遠ざかり、熱水もマグマ水ではなく海水の影響が大きくなるに従って(すなわち熱水域の衰退段階に対応する形で)、ホワイトスモーカーが成立することもある。このタイプのベントから吹き出す熱水はカルシウムが豊富で、主に硫酸塩(重晶石と無水石膏)や炭酸塩に富む堆積物を形成する[1]。

一方で、沖縄トラフの鳩間海丘からは有人潜水調査船しんかい6500による探査により、新たにブルースモーカーが発見された。この色の解明は、今後の調査を待つ段階である[22]。

- ^ a b c d e f g Colín-García, María (2016). “Hydrothermal vents and prebiotic chemistry: a review”. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana 68 (3): 599-620. doi:10.18268/BSGM2016v68n3a13.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (2017年4月13日). “Conditions for Life Detected on Saturn Moon Enceladus”. New York Times 2017年4月14日閲覧。

- ^ “Spacecraft Data Suggest Saturn Moon's Ocean May Harbor Hydrothermal Activity”. NASA. (2015年3月11日) 2015年3月12日閲覧。

- ^ http://www.space.com/missionlaunches/missions/mars_society_conference_010515-1.html

- ^ Weinstein, Stuart A., Olson, Peter L. (1989). “The proximity of hotspots to convergent and divergent plate boundaries”. Geophysical Research Letters 16: 433-436.

- ^ Garcia, Elena Guijarro; Ragnarsson, Stefán Akí; Steingrimsson, Sigmar Arnar; Nævestad, Dag; Haraldsson, Haukur; Fosså, Jan Helge; Tendal, Ole Secher; Eiríksson, Hrafnkell (2007). Bottom trawling and scallop dredging in the Arctic: Impacts of fishing on non-target species, vulnerable habitats and cultural heritage. Nordic Council of Ministers. p. 278. ISBN 978-92-893-1332-2

- ^ Haase, K. M. (2007). “Young volcanism and related hydrothermal activity at 5°S on the slow-spreading southern Mid-Atlantic Ridge”. Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems 8 (11): Q11002. Bibcode: 2007GGG.....811002H. doi:10.1029/2006GC001509.

- ^ Haase, K. M. (2009). “Fluid compositions and mineralogy of precipitates from Mid Atlantic Ridge hydrothermal vents at 4°48'S”. Pangaea. doi:10.1594/PANGAEA.727454.

- ^ Bischoff, James L; Rosenbauer, Robert J (1988). “Liquid-vapor relations in the critical region of the system NaCl-H2O from 380 to 415°C: A refined determination of the critical point and two-phase boundary of seawater”. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 52 (8): 2121-2126. Bibcode: 1988GeCoA..52.2121B. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(88)90192-5.

- ^ A. Koschinsky, C. Devey (2006年5月22日). “Deep-Sea Heat Record: Scientists Observe Highest Temperature Ever Registered at the Sea Floor” (English). International University Bremen. 2006年7月6日閲覧。

- ^ Von Damm, K L (1990). “Seafloor Hydrothermal Activity: Black Smoker Chemistry and Chimneys”. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 18 (1): 173-204. Bibcode: 1990AREPS..18..173V. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.18.050190.001133.

- ^ Haase, K. M. (2007). “Young volcanism and related hydrothermal activity at 5°S on the slow-spreading southern Mid-Atlantic Ridge”. Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems 8 (11): Q11002. Bibcode: 2007GGG.....811002H. doi:10.1029/2006GC001509.

- ^ Haase, K. M. (2009). “Fluid compositions and mineralogy of precipitates from Mid Atlantic Ridge hydrothermal vents at 4°48'S”. Pangaea. doi:10.1594/PANGAEA.727454.

- ^ Tivey, Margaret K. (1998年12月1日). “How to Build a Black Smoker Chimney: The Formation of Mineral Deposits At Mid-Ocean Ridges” (English). Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.. 2006年7月7日閲覧。

- ^ Sid Perkins (2001). “New type of hydrothermal vent looms large”. Science News 160 (2): 21.

- ^ Petkewich, Rachel (September 2008). “Tracking ocean iron”. Chemical & Engineering News 86 (35): 62-63. doi:10.1021/cen-v086n035.p062.

- ^ Douville, E; Charlou, J.L; Oelkers, E.H; Bienvenu, P; Jove Colon, C.F; Donval, J.P; Fouquet, Y; Prieur, D et al. (March 2002). “The rainbow vent fluids (36°14′N, MAR): the influence of ultramafic rocks and phase separation on trace metal content in Mid-Atlantic Ridge hydrothermal fluids”. Chemical Geology 184 (1-2): 37-48. Bibcode: 2002ChGeo.184...37D. doi:10.1016/S0009-2541(01)00351-5.

- ^ Spiess, F. N.; Macdonald, K. C.; Atwater, T.; Ballard, R.; Carranza, A.; Cordoba, D.; Cox, C.; Garcia, V. M. D. et al. (28 March 1980). “East Pacific Rise: Hot Springs and Geophysical Experiments”. Science 207 (4438): 1421-1433. Bibcode: 1980Sci...207.1421S. doi:10.1126/science.207.4438.1421. PMID 17779602.

- ^ “Boiling Hot Water Found in Frigid Arctic Sea”. LiveScience (2008年7月24日). 2008年7月25日閲覧。

- ^ “Scientists Break Record By Finding Northernmost Hydrothermal Vent Field”. Science Daily (2008年7月24日). 2008年7月25日閲覧。

- ^ Cross (2010年4月12日). “World's deepest undersea vents discovered in Caribbean”. BBC News. 2010年4月13日閲覧。

- ^ “0123”. www.jamstec.go.jp. 2020年8月29日閲覧。

- ^ Beatty, J.T. (2005). “An obligately photosynthetic bacterial anaerobe from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102 (26): 9306-10. Bibcode: 2005PNAS..102.9306B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503674102. PMC 1166624. PMID 15967984.

- ^ CSOTONYI Julius T. ; STACKEBRANDT Erko ; YURKOV Vladimir (2006), “Anaerobic respiration on tellurate and other metalloids in bacteria from hydrothermal vent fields in the eastern pacific ocean”, Applied and Environmental Microbiology (American Society for Microbiology) 72 (7): 4950-4956, ISSN 0099-2240, オリジナルの2007年12月17日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2007年7月26日閲覧。

- ^ Astrobiology Magazine: Extremes of Eel City Retrieved 30 August 2007

- ^ Sysoev, A. V.; Kantor, Yu. I. (1995). “Two new species of Phymorhynchus (Gastropoda, Conoidea, Conidae) from the hydrothermal vents”. Ruthenica 5: 17-26.

- ^ Botos, Sonia. “Life on a hydrothermal vent”. 2008年5月14日閲覧。

- ^ Van Dover. “Hot Topics: Biogeography of deep-sea hydrothermal vent faunas”. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. 2020年9月17日閲覧。

- ^ Van Dover 2000[要文献特定詳細情報]

- ^ Lonsdale, Peter (1977). “Clustering of suspension-feeding macrobenthos near abyssal hydrothermal vents at oceanic spreading centers”. Deep Sea Research 24 (9): 857-863. Bibcode: 1977DSR....24..857L. doi:10.1016/0146-6291(77)90478-7.

- ^ Cavanaug eta al 1981[要文献特定詳細情報]

- ^ Felback 1981[要文献特定詳細情報]

- ^ Rau 1981[要文献特定詳細情報]

- ^ Cavanaugh 1983[要文献特定詳細情報]

- ^ Fiala-Médioni, A. (1984). “Ultrastructural evidence of abundance of intracellular symbiotic bacteria in the gill of bivalve molluscs of deep hydrothermal vents”. Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Sciences 298 (17): 487-492.

- ^ Le Pennec, M.; Hily, A. (1984). “Anatomie, structure et ultrastructure de la branchie d'un Mytilidae des sites hydrothermaux du Pacifique oriental” (French). Oceanologica Acta 7 (4): 517-523.

- ^ Flores, J. F.; Fisher, C. R.; Carney, S. L.; Green, B. N.; Freytag, J. K.; Schaeffer, S. W.; Royer, W. E. (2005). “Sulfide binding is mediated by zinc ions discovered in the crystal structure of a hydrothermal vent tubeworm hemoglobin”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102 (8): 2713-2718. Bibcode: 2005PNAS..102.2713F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407455102. PMC 549462. PMID 15710902.

- ^ Thiel, Vera; Hügler, Michael; Blümel, Martina; Baumann, Heike I.; Gärtner, Andrea; Schmaljohann, Rolf; Strauss, Harald; Garbe-Schönberg, Dieter et al. (2012). “Widespread Occurrence of Two Carbon Fixation Pathways in Tubeworm Endosymbionts: Lessons from Hydrothermal Vent Associated Tubeworms from the Mediterranean Sea”. Frontiers in Microbiology 3: 423. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00423. PMC 3522073. PMID 23248622.

- ^ Stein et al 1988[要文献特定詳細情報]

- ^ Biology of the Deep Sea, Peter Herring[要文献特定詳細情報]

- ^ Van Dover et al 1988[要文献特定詳細情報]

- ^ Desbruyeres et al 1985[要文献特定詳細情報]

- ^ de Burgh, M. E.; Singla, C. L. (December 1984). “Bacterial colonization and endocytosis on the gill of a new limpet species from a hydrothermal vent”. Marine Biology 84 (1): 1-6. doi:10.1007/BF00394520.

- ^ Ikuta, Tetsuro; Takaki, Yoshihiro; Nagai, Yukiko; Shimamura, Shigeru; Tsuda, Miwako; Kawagucci, Shinsuke; Aoki, Yui; Inoue, Koji et al. (2016-04). “Heterogeneous composition of key metabolic gene clusters in a vent mussel symbiont population” (英語). The ISME Journal 10 (4): 990–1001. doi:10.1038/ismej.2015.176. ISSN 1751-7362. PMC 4796938. PMID 26418631.

- ^ Yamamoto, Masahiro; Nakamura, Ryuhei; Kasaya, Takafumi; Kumagai, Hidenori; Suzuki, Katsuhiko; Takai, Ken (2017-05-15). “Spontaneous and Widespread Electricity Generation in Natural Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Fields” (英語). Angewandte Chemie International Edition 56 (21): 5725–5728. doi:10.1002/anie.201701768.

- ^ Yamamoto, Masahiro; Nakamura, Ryuhei; Kasaya, Takafumi; Kumagai, Hidenori; Suzuki, Katsuhiko; Takai, Ken (2017-05-15). “Spontaneous and Widespread Electricity Generation in Natural Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Fields” (英語). Angewandte Chemie 129 (21): 5819–5822. doi:10.1002/ange.201701768.

- ^ 生命の起源を解く重要なヒントとなる「海底熱水-液体/超臨界CO2仮説」の提唱 海洋研究開発機構(2022年11月16日)2022年12月9日閲覧

- ^ Dodd, Matthew S.; Papineau, Dominic; Grenne, Tor; Slack, John F.; Rittner, Martin; Pirajno, Franco; O'Neil, Jonathan; Little, Crispin T. S. (2 March 2017). “Evidence for early life in Earth's oldest hydrothermal vent precipitates”. Nature 543 (7643): 60-64. Bibcode: 2017Natur.543...60D. doi:10.1038/nature21377. PMID 28252057.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (2017年3月1日). “Scientists Say Canadian Bacteria Fossils May Be Earth's Oldest”. New York Times 2017年3月2日閲覧。

- ^ Ghosh, Pallab (2017年3月1日). “Earliest evidence of life on Earth 'found'”. BBC News 2017年3月2日閲覧。

- ^ Hannington, M.D. (2014). “Volcanogenic Massive Sulfide Deposits”. Treatise on Geochemistry. pp. 463-488. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-095975-7.01120-7. ISBN 978-0-08-098300-4

- ^ Degens, Egon T. (ed.), 1969, Hot Brines and Recent Heavy Metal Deposits in the Red Sea, 600 pp, Springer-Verlag

- ^ Kathleen., Crane (2003). Sea legs : tales of a woman oceanographer. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. ISBN 9780813342856. OCLC 51553643

- ^ “What is a hydrothermal vent?”. National Ocean Service. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2018年4月10日閲覧。

- ^ Lonsdale, P. (1977). “Clustering of suspension-feeding macrobenthos near abyssal hydrothermal vents at oceanic spreading centers”. Deep-Sea Research 24 (9): 857-863. Bibcode: 1977DSR....24..857L. doi:10.1016/0146-6291(77)90478-7.

- ^ Crane, Kathleen; Normark, William R. (10 November 1977). “Hydrothermal activity and crestal structure of the East Pacific Rise at 21°N”. Journal of Geophysical Research 82 (33): 5336-5348. Bibcode: 1977JGR....82.5336C. doi:10.1029/jb082i033p05336.

- ^ a b “Dive and Discover: Expeditions to the Seafloor”. www.divediscover.whoi.edu. 2016年1月4日閲覧。

- ^ Davis, Rebecca; Joyce, Christopher (2011年12月5日). “The Deep-Sea Find That Changed Biology” (英語). NPR.org 2018年4月9日閲覧。

- ^ Corliss, John B.; Dymond, Jack; Gordon, Louis I.; Edmond, John M.; von Herzen, Richard P.; Ballard, Robert D.; Green, Kenneth; Williams, David et al. (16 March 1979). “Submarine Thermal Springs on the Galápagos Rift”. Science 203 (4385): 1073-1083. Bibcode: 1979Sci...203.1073C. doi:10.1126/science.203.4385.1073. PMID 17776033.

- ^ Spiess, F. N.; Macdonald, K. C.; Atwater, T.; Ballard, R.; Carranza, A.; Cordoba, D.; Cox, C.; Garcia, V. M. D. et al. (28 March 1980). “East Pacific Rise: Hot Springs and Geophysical Experiments”. Science 207 (4438): 1421-1433. Bibcode: 1980Sci...207.1421S. doi:10.1126/science.207.4438.1421. PMID 17779602.

- ^ Francheteau, J (1979). “Massive deep-sea sulphide ore deposits discovered on the East Pacific Rise”. Nature 277 (5697): 523. Bibcode: 1979Natur.277..523F. doi:10.1038/277523a0.

- ^ Macdonald, K. C.; Becker, Keir; Spiess, F. N.; Ballard, R. D. (1980). “Hydrothermal heat flux of the "black smoker" vents on the East Pacific Rise”. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 48 (1): 1-7. Bibcode: 1980E&PSL..48....1M. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(80)90163-6.

- ^ Haymon, Rachel M.; Kastner, Miriam (1981). “Hot spring deposits on the East Pacific Rise at 21°N: preliminary description of mineralogy and genesis” (英語). Earth and Planetary Science Letters 53 (3): 363-381. Bibcode: 1981E&PSL..53..363H. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(81)90041-8.

- ^ “New undersea vent suggests snake-headed mythology”. EurekaAert. (2007年4月18日) 2007年4月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Beebe”. Interridge Vents Database. 2020年9月17日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “カリブの海底に世界最深の熱水噴出孔”. National Geographic News. (2010年4月13日) 2016年6月14日閲覧。

- ^ a b “噴き出す黒煙、世界最深の熱水噴出孔”. National Geographic News. (2012年1月10日) 2016年6月14日閲覧。

- ^ German, C. R. (2010). “Diverse styles of submarine venting on the ultraslow spreading Mid-Cayman Rise”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (32): 14020-5. Bibcode: 2010PNAS..10714020G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009205107. PMC 2922602. PMID 20660317 2010年12月31日閲覧。.

- ^ a b “カリブ海の世界最深の噴出孔で新種続々発見、目のないエビなど”. AFPBB News. (2012年1月12日) 2012年1月12日閲覧。

- ^ Shukman, David (2013年2月21日). “Deepest undersea vents discovered by UK team”. BBC News 2013年2月21日閲覧。

- ^ Broad, William J. (2016年1月12日). “The 40,000-Mile Volcano”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 2016年1月17日閲覧。

- ^ Leal-Acosta, María Luisa; Prol-Ledesma, Rosa María (2016). “Caracterización geoquímica de las manifestaciones termales intermareales de Bahía Concepción en la Península de Baja California” (Spanish). Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana 68 (3): 395-407. doi:10.18268/bsgm2016v68n3a2. JSTOR 24921551.

- ^ Beaulieu, Stace E.; Baker, Edward T.; German, Christopher R.; Maffei, Andrew (November 2013). “An authoritative global database for active submarine hydrothermal vent fields”. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 14 (11): 4892-4905. Bibcode: 2013GGG....14.4892B. doi:10.1002/2013GC004998.

- ^ Rogers, Alex D.; Tyler, Paul A.; Connelly, Douglas P.; Copley, Jon T.; James, Rachael; Larter, Robert D.; Linse, Katrin; Mills, Rachel A. et al. (3 January 2012). “The Discovery of New Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vent Communities in the Southern Ocean and Implications for Biogeography”. PLoS Biology 10 (1): e1001234. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001234. PMC 3250512. PMID 22235194.

- ^ Perkins, W. G. (1 July 1984). “Mount Isa silica dolomite and copper orebodies; the result of a syntectonic hydrothermal alteration system”. Economic Geology 79 (4): 601-637. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.79.4.601.

- ^ We Are About to Start Mining Hydrothermal Vents on the Ocean Floor. Nautilus; Brandon Keim. 12 September 2015.

- ^ Ginley (2014年). “Categorizing mineralogy and geochemistry of Algoma type banded iron formation, Temagami, ON”. 2017年11月14日閲覧。

- ^ “Liberating Japan's resources”. The Japan Times. (2012年6月25日)

- ^ Government of Canada (2017年1月23日). “Mining Sector Market Overview 2016 - Japan”. www.tradecommissioner.gc.ca. 2019年3月11日閲覧。

- ^ "Nautilus Outlines High Grade Au - Cu Seabed Sulphide Zone" (Press release). Nautilus Minerals. 25 May 2006. 2009年1月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。

- ^ “Neptune Minerals”. 2012年8月2日閲覧。

- ^ We Are About to Start Mining Hydrothermal Vents on the Ocean Floor. Nautilus; Brandon Keim. 12 September 2015.

- ^ Birney. “Potential Deep-Sea Mining of Seafloor Massive Sulfides: A case study in Papua New Guinea”. University of California, Santa Barbara, B[リンク切れ]. 2020年9月16日閲覧。

- ^ “Treasures from the deep”. Chemistry World. (January 2007).

- ^ Amon, Diva; Thaler, Andrew D. (2019-08-06). “262 Voyages Beneath the Sea: a global assessment of macro- and megafaunal biodiversity and research effort at deep-sea hydrothermal vents” (英語). PeerJ 7: e7397. doi:10.7717/peerj.7397. ISSN 2167-8359.

- ^ The secret on the ocean floor. David Shukman, BBC News. 19 February 2018.

- ^ Devey, C.W.; Fisher, C.R.; Scott, S. (2007). “Responsible Science at Hydrothermal Vents”. Oceanography 20 (1): 162-72. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2007.90.

- ^ Johnson, M. (2005). “Oceans need protection from scientists too”. Nature 433 (7022): 105. Bibcode: 2005Natur.433..105J. doi:10.1038/433105a. PMID 15650716.

- ^ Johnson, M. (2005). “Deepsea vents should be world heritage sites”. MPA News 6: 10.

- ^ Tyler, P.; German, C.; Tunnicliff, V. (2005). “Biologists do not pose a threat to deep-sea vents”. Nature 434 (7029): 18. Bibcode: 2005Natur.434...18T. doi:10.1038/434018b. PMID 15744272.

- 熱水噴出孔のページへのリンク