デトックス

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2024/01/01 06:34 UTC 版)

毒素の定義

「デトックス」という用語の「毒素」の定義は曖昧である[4][17]。

危険物質の摂取量と人体影響の関係

デトックスにおける「毒素」には有害金属だけでなくダイオキシンやPCBなどの有害化学物質を含める人もいる[5]。ほとんどの人間の体内にある農薬やその他の汚染物質の量は、極めて微量であり、そのわずかな物質がすぐに有害で、減らせば健康に良いというわけでもない[6]。地球上に存在するもののほとんどは人の体内にも存在し、「在るから有害」なのではではない[233]。

化学物質とは、原子・分子や、分子の集合体などを指す言葉で、人体や食品も全て化学物質で構成される[234]。体内に入った化学物質はふつうはたまり続けることはなく、一定の量までは悪影響が現れない[234][235]。人の体には、排泄や代謝・分解機能があり、口から入った物は、腸管を素通りして排泄されるものと、腸管から吸収され、肝臓で代謝されて尿や便と一緒に排出されるものがある[235][233]。食品のリスク(その食品を食べることによって病的な症状が現れる確率)は、強い毒性を持つ有害成分を含む食品でも摂取量が僅かならば障害は生じず、逆に毒性は弱くてもその食品を大量に摂取すれば毒性徴候が現れるという原則がある[236]。例えば、水や塩も過剰摂取による死亡例がある[235][237]。メチル水銀は、耐容一日摂取量(TDI)以下ならば、一生涯健康への悪影響は起こらないが、水俣病患者では1mg/日以上という大量のメチル水銀を摂取し続けたため、中枢神経障害が生じている[233]。「耐容一日摂取量(TDI)」は、食品中に存在する物質(重金属、かび毒等)について、ヒトが一生涯にわたって毎日摂取し続けても、健康への悪影響がないと推定される一日当たりの摂取量のことである[238][239]。ごく微量のハザード(健康に悪影響をもたらす可能性のある食品中の物質または食品の状態)は、毎日摂り続けても健康障害を起こさないレベルで一定となるので、蓄積されて健康被害を生じることはない[233]。

具体例

食品添加物

食品安全委員会などが行う「リスク評価(食品健康影響評価)」では、国によって食品の摂取量などの状況は異なるため、各国の現状に近い摂取量に基づきリスク評価が行われる[238]。

食品添加物については、安全性を確保するため、動物実験によって無害とされた量(無毒性量)について、その無毒性量の100分の1以上の安全係数を掛けて、人が一生涯食べ続けても健康に悪影響を与えない量、すなわち「一日摂取許容量(ADI)」が設定される[240][233][241]。摂取許容量(無毒性量の100分の1以下の量)より大幅に少ない量が法令上の基準値とされた上に、実際に使用される量は基準より更に大幅に少ない[240]。このように食品添加物は、毎日・一生食べても安全な範囲でのみ使用される[240][242]。

農薬

農薬についても、あらゆる実験動物の中で最も感受性が高い動物に対する無毒性量の1/100以下の量が設定され、人が一生の間毎日摂取しても害がない範囲でのみ使用される[236][243]。

天然物と合成物

「天然、自然」は必ずしも「安全」で体に良いとは言えず[105][246][45][247]、人に健康被害を与える毒性は、天然物も合成物も変わらない[248][249]。天然成分は、それを産出する生物の生理やライフサイクルに適合するように、その体内で作り出した化学物質であり、人間の生理に最適化されたものではない[248][235]。一般に合成物は、開発段階で人の生理やライフサイクルに適合するように最適化され、有用な活性を示しながら負の影響を軽減するように作り出されている[248]。

チメロサール

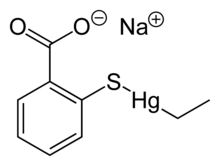

一部のワクチンに含まれるチメロサールなどの添加物が、体内に蓄積され、自閉症などの健康被害を引き起こすと考える人もいる[101][250]。チメロサールは、エチル水銀を含むため、水俣病で問題になったメチル水銀と混同されたこともあり自閉症の原因ではないかと疑われた[252][253][250]。しかし、エチル水銀の半減期はメチル水銀よりはるかに短く、体内で速やかに分解され排出される[250][254][255]。また、現在では、インフルエンザワクチンの一部の製剤を除き、一般的に用いられているすべてのワクチンに、チメロサールは用いられていない[256][255]。インフルエンザワクチンの一部に含まれる量は、最大でも1回1 - 4 μgであり、これは農林水産省の定めた魚介類を食べた際に摂取する総水銀の基準摂取量=体重1 kgあたり4 μg/週(3歳児の平均13 - 14 kgで52 - 56 μg)を大きく下回る[250][257][251][258][259]。妊婦が毎週食べ続けても安全なマグロ(クロ、メバチ)の摂食量は、80 g程度/週=水銀量は43.2 μgであり[260][261]、年1 - 2回のワクチンの水銀は、妊婦に許容される水銀摂取量と比べても微量である[260][261]。また、オランダで約12.5万人を対象にしたコホート研究は、ワクチン接種で自閉症は増加しないという結果だった[250][262]。「ワクチン接種で自閉症になる」と虚偽の論文を書いてデマを広めたイギリスのアンドリュー・ウェイクフィールド医師は、医師免許剥奪の処分を受けている[263][264]。その後、その内容は何度も検証され、否定する論文がいくつも出ているが、未だにデマは根強く残っている[265][266]。

アルミニウム

ワクチンに含まれるアルミニウムなどの添加物が、体内に蓄積され、健康被害を引き起こすと考える人もいる[101]。アルミニウムは、アジュバント(補助剤)として免疫反応を増強するために用いられ[267][268][269]、場合によっては、発赤、痒み、微熱を伴うことがあるが[268]、重篤な有害事象とは関係がない[267][270]。アルミニウム含有ワクチンで生じる局所的マクロファージ性筋膜炎 (MMF) が全身の機能異常と関連すると主張する研究もあるが、近年の症例対照研究では、MMF病変が認められる個人に特異な臨床症状は見つからず、アルミニウム含有ワクチンが重篤な健康リスクをもたらすという根拠は存在しない[267][270][271]。また、ヒトはワクチンよりも、食品や飲料水で日常的に大量の天然由来アルミニウムを摂取している[272][273][274]。アジュバントを含むワクチンは、使用が許可される前に臨床試験で安全性と有効性が確認され、承認後もCDCとFDAによって継続的に監視されている[275]。

アマルガム修復物

デトックスの専門家は、体内の重金属を除去するためにアマルガム修復物(銀歯)の除去を勧めることがある[276]。しかし、アマルガムは口の中で化学的に安定しており、体に何らかの影響を及ぼすことはない[277]。アマルガム合金に使用される水銀は、水俣病の原因になった有機水銀(メチル水銀)とは異なり、合金粉末と混ざった無機水銀である[278][60]。また、コンポジットレジンや他の金属などの技術の改良により、日本では1980年代から急速に使用されなくなり、2016年4月に保険適用から外れて使われなくなっている[277][278][276][60]。アマルガム修復物は、削って外す際に水銀が蒸気化して吸い込むリスクがあるため、虫歯ができたなどの医療上の理由がない場合は外さないほうがよい[277][278]。健康関連の詐欺を監視するウェブサイト「Quackwatch」は、「良い詰め物を取り除くことは単なるお金の無駄遣いではなく、詰め物をとる際に周囲の歯質の一部も取り除かれるため、結果的に歯を失うケースもある」と指摘している[276]。アマルガム修復が安全で有効なことは、国際歯科連盟、アメリカ歯科医師会、日本歯科保存学会などの世界中の多くの歯科協会や歯科公衆衛生機関、その他の組織が公言している[278][279][280][281][282][283][284][285][286]。

- ^ a b c d e “Rusty results”. Ben Goldacre (2004年9月2日). 2013年3月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s 左巻健男『ニセ科学を見抜くセンス』新日本出版社、2015年9月29日。ISBN 978-4406059374。

- ^ a b c d e “'Detox' tincture Q&A”. イギリス国民保健サービス (NHS) (2009年3月11日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g “デトックス”. 疑似科学を科学的に考える(明治大学科学コミュニケーション研究所) (2019年12月10日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e 左巻健男+RikaTan委員『RikaTan (理科の探検) 2018年4月号「特集 ニセ科学を斬る! 2018」』株式会社 文理、2018年2月26日、60-61頁。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m “「汗をかいてデトックス」はウソだった、研究報告”. National Geographic (2018年4月13日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “「SNSで話題の足裏パッドで毒素は除去されない」と専門家、じゃああの汚れの正体は?”. Newsweek (2022年6月29日). 2023年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g “Detox press release”. Sense about Science. 2013年8月26日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2013年4月10日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e “根拠ない代替医療 デトックスだけではなく「クレンジング」にも注意”. 朝日新聞アピタル (2022年7月4日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g ““Detoxes” and “Cleanses”: What You Need To Know”. 米国国立補完統合衛生センター(National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health:NCCIH). 2023年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ “デトックスは医学的な意味の解毒とはかけ離れた怪しいキーワードです”. 五本木クリニック(桑満おさむ) (2022年4月6日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b Klein, AV; Kiat, H (December 2015). “Detox diets for toxin elimination and weight management: a critical review of the evidence.”. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics 28 (6): 675–686. doi:10.1111/jhn.12286. PMID 25522674.

- ^ Zeratsky, Katherine (2012年4月21日). “Do detox diets offer any health benefits?”. Mayo Clinic. 2015年5月9日閲覧。 “デトックスダイエットが実際に体内から毒素を除去するという証拠はほとんどない。腎臓と肝臓は、一般に摂取した毒素のほとんどをろ過して除去するのに非常に効果的である”

- ^ a b “Man dies after favoring detox and forgoing dialysis”. The Sydney Morning Herald (2005年4月27日). 2012年3月22日閲覧。

- ^ Mohammadi, Dara (2014年12月5日). “You can't detox your body. It's a myth. So how do you get healthy?”. The Guardian (Guardian News & Media Limited) 2019年6月26日閲覧. "デトックスとは、体内の不純物を洗い流して、内臓を清潔な状態に保ち、元気に活動できるというものだが、これは詐欺である。それは、あなたに物を売るために作られた疑似医療の概念である。"

- ^ a b Porter, Sian (2016年5月). “Detox diets”. British Dietetic Association. 2016年10月17日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年1月29日閲覧。 “デトックスという考え方はナンセンスです。身体はよく発達したシステムであり、老廃物や毒素を解毒し除去するためのメカニズムが内蔵されています。私たちの体は、アルコール、薬、消化物、死んだ細胞、化学物質、細菌などの毒素や老廃物を常にろ過し、分解して排泄しています”

- ^ a b c d “デトックスで毒素を排出しよう!って言っても、その毒素ってなんだい?”. 五本木クリニック (2022年4月6日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b “健康食品に関する景品表示法及び健康増進法上の留意事項について” (PDF). 消費者庁 (2022年12月5日). 2023年6月9日閲覧。

- ^ “医薬品的な効能効果について”. 東京都健康福祉局. 2021年7月23日閲覧。

- ^ “インターネットにおける健康食品等の虚偽・誇大表示に 対する要請について(令和3年10月~12月)” (PDF). 消費者庁 (2022年3月8日). 2023年6月9日閲覧。

- ^ 渡辺毅「3)肝臓と腎臓」『日本内科学会雑誌』、3.内科医が知っておくべき腎臓と全身臓器とのインターラクション第100巻、第9号、日本内科学会、2544-2551頁、2011年。doi:10.2169/naika.100.2544。ISSN 00215384。PMID 22117349。CRID 1390001206447786880。2023年8月24日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g Klein AV, Kiat H (2015-12). “Detox diets for toxin elimination and weight management: a critical review of the evidence”. J Hum Nutr Diet 28 (6): 675–86. doi:10.1111/jhn.12286. PMID 25522674.

- ^ a b 岡田芳明「薬物中毒の治療 特に体内からの除去」『臨床化学』第31巻第2号、2002年、113-118頁、doi:10.14921/jscc1971b.31.2_113、NAID 130003357361。

- ^ a b 成瀬暢也「精神作用物質使用障害の入院治療 「薬物渇望期」の対応法を中心に」(pdf)『精神神經學雜誌』第112巻第7号、2010年7月25日、665-671頁、NAID 10028059133。

- ^ Kovacs, Jenny Stamos (2007年2月8日). “Colon Cleansers: Are They Safe? Experts discuss the safety and effectiveness of colon cleansers”. WebMD. 2010年6月23日閲覧。

- ^ Biology: A Modern Introduction. Oxford University Press. (1987). pp. 110. ISBN 0-19-914260-2

- ^ a b c “ジュースクレンズって単なるプチ断食だよね、毒素なんて出ないよね⁉”. 五本木クリニック(桑満おさむ) (2021年6月6日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b 田中稔「肝臓と化学 体の化学工場」『化学と教育』第65巻第8号、2017年、404-405頁、doi:10.20665/kakyoshi.65.8_404、NAID 130006328390。

- ^ “Chelation Therapy | Michigan Medicine” (英語). www.uofmhealth.org. 2021年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ Aaseth, Jan; Crisponi, Guido; Anderson, Ole (2016). Chelation Therapy in the Treatment of Metal Intoxication. Academic Press. pp. 388. ISBN 9780128030721

- ^ a b “Chelation Therapy”. American Cancer Society (2008年11月1日). 2010年7月5日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2013年9月14日閲覧。

- ^ “Deaths Associated with Hypocalcemia from Chelation Therapy - Texas, Pennsylvania, and Oregon, 2003-2005”. www.cdc.gov. 2016年10月13日閲覧。

- ^ “Chelation: Therapy or "Therapy"?”. poison.org. National Capital Poison Center (2013年5月6日). 2013年10月9日閲覧。

- ^ Atwood, K.C., IV; Woeckner, E.; Baratz, R.S.; Sampson, W.I. (2008). “Why the NIH Trial to Assess Chelation Therapy (TACT) should be abandoned”. Medscape Journal of Medicine 10 (5): 115. PMC 2438277. PMID 18596934.

- ^ National Clinical Guideline Centre (2010). “2 Acute Alcohol Withdrawal” (英語). Alcohol Use Disorders: Diagnosis and Clinical Management of Alcohol-Related Physical Complications (No. 100 ed.). London: Royal College of Physicians (UK) 2016年10月21日閲覧。

- ^ 友田吉則、福本真理子「解毒薬 活性炭」『The Japanese journal of clinical toxicology』第31巻第1号、2018年、41-46頁。(

要購読契約)

要購読契約)

藤田基、鶴田良介「解毒薬 アトロピン」『The Japanese journal of clinical toxicology』第30巻第4号、2017年、391-394頁。 岡崎敬之介、峯村純子「解毒薬 ナロキソン塩酸塩」『The Japanese journal of clinical toxicology』第30巻第3号、2017年、261-266頁。 堺淳「解毒薬 ヘビの抗毒素」『The Japanese journal of clinical toxicology』第30巻第1号、2017年、41-45頁。 髙野博徳、遠藤容子、黒木由美子「解毒薬 キレート剤」『The Japanese journal of clinical toxicology』第29巻第3号、2016年、259-263頁。 福本真理子「解毒薬(1)N-アセチルシステイン」『The Japanese journal of clinical toxicology』第26巻第2号、2013年、129-133頁。 - ^ a b “The science behind diet trends like Mono, charcoal detox, Noom and Fast800”. The Conversation (2019年8月28日). 2019年8月27日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年12月2日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Top ten signs your detox may be a scam”. Science Based Medicine (2017年12月28日). 2018年2月2日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年11月30日閲覧。

- ^ Eddleston, Michael; Juszczak, Edmund; Buckley, Nick A.; Senarathna, Lalith; Mohamed, Fahim; Dissanayake, Wasantha; Hittarage, Ariyasena; Azher, Shifa et al. (2008). “Multiple-dose activated charcoal in acute self-poisoning: a randomised controlled trial”. The Lancet 371 (9612): 579–587. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60270-6. PMC 2430417. PMID 18280328.

- ^ “"Detox": Ritual purification masquerading as medicine and wellness”. Science Based Medicine (2017年1月30日). 2017年2月3日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年11月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b “体から毒素を排出? いわゆる「デトックス」に医学的な根拠はない”. 朝日新聞アピタル (2020年6月20日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ “デトックスは本当に効果があるのでしょうか?”. LES MILLS (2022年6月29日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b “「デトックス」は幻想だった? 5つの手法を“科学的”に分析した結果”. wired (2019年5月31日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ Carroll, RT (2010年4月24日). “Detoxification therapies”. Skepdic.com. 2010年6月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f “「擬似(ニセ)医療」に気をつけろ”. 鳥取大学医学部附属病院. 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k “【リクエスト】ダイエット目的の腸管洗浄やコーヒー浣腸にご用心(コラム:医師も戸惑う健康情報)”. 日経メディカル (2003年2月24日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f “Colon Therapy”. American Cancer Society. 2015年4月24日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ Cook, Harold (2001). “From the Scientific Revolution to the Germ Theory”. In Loudon, Irvine. Western Medicine: An Illustrated History (reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780199248131 2015年8月21日閲覧. "1830年頃までには、瀉血など、確立された治療法の多くが実際には役に立たないか、悪いものであるという見方が広まってきたため、旧式の医術を揶揄することが容易になった。"

- ^ Alvarez, Walter C. (1919-01-04). “Origin of the so-called auto-intoxication symptoms”. JAMA 72 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1001/jama.1919.02610010014002.

- ^ Compare: Wanjek, Christopher (2006年8月8日). “Colon Cleansing: Money Down the Toilet”. LiveScience. 2008年11月10日閲覧。 “大腸洗浄は侵襲性の高い方法で、この習慣がいつ始まったのかは明らかではない。 アメリカにおける大腸洗浄の黄金時代は19世紀後半で、真面目な考えを持つ医師たちが大腸自家中毒説を唱えた。腸は下水道であり、便秘で体内に汚水溜りができ、食物の老廃物は腐敗して毒性を帯び、腸から再吸収されるというものであった。 また、一部の科学者は、便秘によって糞便が何カ月も何年も腸壁にこびりつき、栄養の吸収が妨げられると主張した(それでもなぜか毒素は遮断されない)。自家中毒の(最初の)時代の終わりの始まりは、1919年にW.C.アルバレスがJournal of the American Medical Associationに発表した論文だった。今日に至るまで、手術や剖検によって大腸を直接観察しても、腸壁に沿って糞便が硬化することはなく、汚水溜りもない。1920年代までには、大腸洗浄はヤブ医者の領域に追いやられた。”

- ^ a b Ernst, Edzard (June 1997). “Colonic irrigation and the theory of autointoxication: a triumph of ignorance over science”. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 24 (4): 196–98. doi:10.1097/00004836-199706000-00002. PMID 9252839.

- ^ Chen, Thomas S. N.; Chen, Peter S. Y. (1989). “Intestinal autointoxication: a medical leitmotif”. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 11 (4): 434–41. doi:10.1097/00004836-198908000-00017. PMID 2668399.

- ^ Adams, Cecil (1990年5月25日). “Does colonic irrigation do you any good?”. The Straight Dope. 2008年9月2日閲覧。

- ^ Bitar, Adrienne Rose (January 2018). Diet and the Disease of Civilization. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-8964-0

- ^ a b “自閉症児の親たちが入り込む「フィルターバブル」の闇”. buzzfeed (2017年9月29日). 2023年6月21日閲覧。

- ^ Ernst, E. (2000). “Chelation therapy for coronary heart disease: An overview of all clinical investigations”. American Heart Journal 140 (1): 139–141. doi:10.1067/mhj.2000.107548. PMID 10874275.

- ^ Weber, W.; Newmark, S. (2007). “Complementary and alternative medical therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism”. Pediatric Clinics of North America 54 (6): 983–1006. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2007.09.006. PMID 18061787.

- ^ “Boy with autism dies during 'chelation therapy'”. Behavior News. Behavior Analysis Association of Michigan (2005年8月30日). 2016年11月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b American College of Medical Toxicology; American Academy of Clinical Toxicology (February 2013), “Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question”, Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation (American College of Medical Toxicology and American Academy of Clinical Toxicology) 2013年12月5日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “アマルガム合金”. 横浜・中川駅前歯科クリニック. 2023年6月9日閲覧。

- ^ 日本小児神経学会, 日本小児精神神経学会, 日本小児心身医学会「学会の窓 : 自閉症における水銀・チメロサールの関与に関する声明」『脳と発達』第36巻第5号、2004年、441-443頁、doi:10.11251/ojjscn1969.36.441、2023年8月24日閲覧。

- ^ Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (14 October 2010). "FDA issues warnings to marketers of unapproved 'chelation' products" (Press release). 2017年1月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。

- ^ “Why Chelation Therapy Should Be Avoided”. Quackwatch (2004年5月15日). 2013年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ “FDA links child deaths to chelation therapy”. NBC News / Associated Press. (2006年2月3日). オリジナルの2018年8月30日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2018年8月30日閲覧。

- ^ Weber, W.; Newmark, S. (2007). “Complementary and alternative medical therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism”. Pediatric Clinics of North America 54 (6): 983–1006. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2007.09.006. PMID 18061787.

- ^ Davis, Tonya N.; O'Reilly, Mark; Kang, Soyeon; Lang, Russell et al. (2013). “Chelation treatment for autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review”. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 7 (1): 49–55. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2012.06.005. "However, given the significant methodological limitations of these studies, the research reviewed here does not support the use of chelation as a treatment for ASD"

- ^ Blakeslee, Sandra (2004年5月19日). “Panel finds no evidence to tie autism to vaccines”. New York Times 2008年2月1日閲覧。

- ^ Blaucok-Busch, E.; Amin, O.R.; Dessoki, H.H.; Rabah, T. (2012). “Efficacy of DMSA therapy in a sample of Arab children with autistic spectrum disorder”. Mædica 7 (3): 214–21. PMC 3566884. PMID 23400264.

- ^ Adams, J.B.; Baral, M.; Geis, E.; Mitchell, J. et al. (2009). “Safety and efficacy of oral DMSA therapy for children with autism spectrum disorders: Part B - Behavioral results”. BMC Clinical Pharmacology 9: 17. doi:10.1186/1472-6904-9-17. PMC 2770991. PMID 19852790.

- ^ Adams, J.B.; Baral, M.; Geis, E.; Mitchell, J. et al. (2009). “The severity of autism is associated with toxic metal body burden and red blood cell glutathione levels”. Journal of Toxicology 2009: 532640. doi:10.1155/2009/532640. PMC 2809421. PMID 20107587.

- ^ Adams, J.B.; Baral, M.; Geis, E.; Mitchell, J. et al. (2009). “Safety and efficacy of oral DMSA therapy for children with autism spectrum disorders: Part A - Medical results”. BMC Clinical Pharmacology 9: 16. doi:10.1186/1472-6904-9-16. PMC 2774660. PMID 19852789.

- ^ CG142 - Autism spectrum disorder in adults: diagnosis and management (Report). 英国国立医療技術評価機構. 2012-06. Chapt.1.4.

{{cite report}}:|date=の日付が不正です。 (説明) - ^ a b c d e “Activated charcoal: The latest detox fad in an obsessive food culture”. Science Based Medicine (2015年5月7日). 2015年5月26日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年11月27日閲覧。

- ^ “デトックス素材として話題の活性炭を配合! ダイエッターをサポートするサプリメント「活性炭DIET」が新発売!”. prtimes(日本薬健) (2018年9月21日). 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Activated charcoal doesn't detox the body – four reasons you should avoid it”. The Conversation (2018年6月12日). 2018年6月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年11月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b “What Is Activated Charcoal Used For, and Does it Really Work?”. The New York Times (2019年10月16日). 2019年10月16日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年11月30日閲覧。

- ^ a b “It's in smoothies, toothpaste and pizza – is charcoal the new black?”. The Guardian (2017年6月28日). 2017年7月1日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年11月30日閲覧。

- ^ “Do yourself a detox favor: Skip the activated-charcoal latte with an alkaline water chaser.”. The Seattle Times (2019年11月25日). 2019年11月30日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年11月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Charcoal has become the hot new flavouring in everything from cocktails to meat and mash”. The Independent (2015年4月9日). 2015年4月12日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年11月30日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i “「トンデモ」な健康情報には見分け方がある”. 東洋経済新報社 (2017年2月11日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ “Can POPs be substantially popped out through sweat?”. Environment International Volume 111, February 2018, Pages 131-132. 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b 足裏から毒素”はニセ科学!? 毎日放送 VOICE (2007年3月9日)

- ^ a b c d Barrett, Stephen (2011年6月8日). “'Detoxification' Schemes and Scams”. Quackwatch. 2023年6月6日閲覧。

- ^ “Japanese Foot Pad Is Latest Health Fad”. npr (2008年8月18日). 2023年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Objective assessment of an ionic footbath (IonCleanse): testing its ability to remove potentially toxic elements from the body”. J Environ Public Health . 2012;2012:258968. doi: 10.1155/2012/258968. Epub 2011 Nov 29. (2011年11月29日). 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ “Fact check: No evidence that foot pads can detoxify the body, experts say”. usatoday (2022年6月14日). 2023年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g “「宿便解消」をうたうデトックス法に注意 体重は減りません”. 朝日新聞アピタル (2022年6月27日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b “便秘”. MSDマニュアル プロフェッショナル版. 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ “便秘に悩み続けた松本明子さん、宿便4キロ解消の道のり”. 朝日新聞アピタル (2018年12月2日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f “ゲルソン療法(PDQ®)”. がん情報サイト(神戸医療産業都市推進機構). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d “「コーヒー浣腸」って健康に良いの?”. Yahoo! (2015年12月3日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ “キャンドルブッシュを含む健康茶 ―下剤成分(センノシド)を含むため過剰摂取に注意―” (PDF). 独立行政法人国民生活センター (2014年1月23日). 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ “Do you really need to clean your colon?”. Marketplace (CBC Television). (2009年). オリジナルの2010年3月15日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2010年5月3日閲覧。

- ^ a b Michael F. Picco, M.D. (2018年4月26日). “Is colon cleansing a good way to eliminate toxins from your body?”. Consumer Health. Mayo Clinic. 2020年1月5日閲覧。

- ^ a b 日本消化器病学会関連研究会慢性便秘の診断治療研究会『慢性便秘症診療ガイドライン2017』南江堂、2017年10月3日。ISBN 978-4524255757。

- ^ a b “経肛⾨的洗腸療法の適応及び指導管理に 関する指針” (PDF). 日本⼤腸肛⾨病学会 (2021年10月12日). 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ “[Coffee enema induced acute colitis”] (Korean). Korean J Gastroenterol 52 (4): 251–4. (October 2008). PMID 19077527.

- ^ “Gerson Therapy”. American Cancer Society. 2009年4月20日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2009年4月22日閲覧。

- ^ “BDA Releases Top 5 Celeb Diets to Avoid in 2019”. British Dietetic Association (2018年12月7日). 2021年7月9日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ Eisenbraun, Karen (2011年6月14日). “A Detox Diet That Works”. LiveStrong. 2012年11月9日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d 内山葉子『毒だらけ 病気の9割はデトックスで防げる!』評言社、2018年1月17日。ISBN 978-4828205939。

- ^ “The Truth About Detox Diets”. www.WebMD.com. 2019年2月2日閲覧。

- ^ "Woman left brain damaged by detox". BBC News. 23 July 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Obert J, Pearlman M, Obert L, Chapin S (November 2017). “Popular Weight Loss Strategies: a Review of Four Weight Loss Techniques”. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 19 (12): 61. doi:10.1007/s11894-017-0603-8. PMID 29124370.

- ^ a b c d e f g h “肥満(体重管理)、「デトックス」および「クレンジング」知っておくべきこと”. 厚生労働省eJIM. 2023年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Ismael San Mauro Martín, Victor Paredes Barato, Sara Sanz Rojo et al (2017). “Are detox diets an effective strategy for obesity and oxidation management in the short term?” (PDF). JONNPR 2 (9): 399-409. doi:10.19230/jonnpr.1585.

- ^ “Detox Diets: Cleansing the Body”. WebMD. 2010年6月23日閲覧。

- ^ Moores, Susan. "Experts warn of detox diet dangers". NBC News. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ “Do Juice Cleanses Work? 10 Truths About The Fad”. www.huffingtonpost.ca. Huffington Post (2012年3月22日). 2019年2月2日閲覧。

- ^ a b “The dubious practice of detox”. Harvard Women's Health Watch. Harvard Medical School (2008年5月). 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ Clarke, Jane. “The nutritionist's view”. The Times (London UK): pp. 4. オリジナルの2020年8月18日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2008年1月30日閲覧。

- ^ "Juicing -- Fad or Fab?". Retrieved 22 December 2019. "No published research currently supports the safety or efficacy of juice cleanses or fasts".

- ^ Frey, Rebecca J. (2008). Juice fasts. In Jacqueline L. Longe. The Gale Encyclopedia of Diets: A Guide to Health and Nutrition. The Gale Group. p. 594. ISBN 978-1-4144-2991-5

- ^ Stanley Burroughs (1976). The Master Cleanser. Burroughs Books. pp. 16–22, 25. ISBN 978-0-9639262-0-3

- ^ a b c d e “最近よく見かける「酵素」って健康に良いの?”. Yahoo!(成田崇信) (2015年11月9日). 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ a b “酵素は体にいい?酸性食品は悪い?消化に関する6つの迷信”. lifehacker (2015年7月14日). 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h 桑満おさむ『“意識高い系"がハマる「ニセ医学」が危ない! 第2章「酵素」「デットクス」と聞いたら要注意!』扶桑社、2019年9月27日。ISBN 978-4594083052。

- ^ 左巻健男+RikaTan委員『RikaTan (理科の探検) 2017年4月号「特集 ニセ科学を斬る! 2017」』株式会社 文理、2017年2月25日、66-71「酵素、発酵、酵母 - ごっちゃになってません?安全でおいしい食生活のためにだまされてはいけないこと(小波秀雄)」頁。

- ^ “発酵ジュースと酵素ジュース”. 日本発酵文化協会 (2015年8月3日). 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ “静岡のホテル、「手の常在菌を使って発酵ジュース」で謝罪、提供停止 保健所が立ち入り調査”. 産経新聞 (2023年4月27日). 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ “豆乳に新生児の手を入れてぐるぐるかき回す「赤子ヨーグルト」に発酵食品の神秘を感じている人たちへ”. wezzy. 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ “Here's How a Cabbage Juice "Cult" with 58,000 Followers Set off a Facebook War”. BuzzFeed News. 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ Subbaraman, Nidhi (2018年3月17日). “Here's How A "Poop Cult" With 58,000 Followers Set Off A Facebook War”. Buzzfeed News. 2019年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Jilly Juice - Business Details”. Better Business Bureau. 2020年1月6日閲覧。

- ^ Schwarcz, Joseph (2018年6月1日). “The Right Chemistry: Beware of self-proclaimed health experts”. Montreal Gazette. 2020年1月5日閲覧。

- ^ Gander, Kashmira (2018年5月3日). “Woman Who Claims Cabbage Juice 'Cures' Autism and Can Regrow Limbs to be Probed by Officials”. Newsweek. 2019年1月5日閲覧。

- ^ a b “EMなどのニセ科学とどう向き合うか”. Web第三文明 (2013年12月22日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b “放射線対策に「米のとぎ汁乳酸菌」 専門家から効果に疑問の声”. J-CASTニュース (2011年7月28日). 2023年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ “「米のとぎ汁が放射能に効く」は健康を損なう恐れあり”. 日刊SPA! (2011年8月1日). 2023年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ Russell, Sharman Apt; Russell, Sharman (1 August 2008) (英語). Hunger: An Unnatural History. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0786722396. オリジナルの2 February 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。 2017年1月22日閲覧。

- ^ a b Griffith, R. Marie. (2000). Apostles of Abstinence: Fasting and Masculinity during the Progressive Era. American Quarterly 52 (4): 599-638.

- ^ Kuske, Terrence T. (1983). Quackery and Fad Diets Archived 20 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine.. In Elaine B. Feldman. Nutrition in the Middle and Later Years. John Wright & Sons. pp. 291-303. ISBN 0-7236-7046-3

- ^ “スティーブ・ジョブズにインスピレーションを与え続けた14冊の本”. businessinsider (2019年5月19日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b “同じ野菜を食べ続ける、断食をする ── スティーブ・ジョブズ、こだわりの食生活”. businessinsider (2019年8月2日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ Hall, Harriett. (2016). "Natural Medicine, Starvation, and Murder: The Story of Linda Hazzard" Archived 1 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine.. Science-Based Medicine. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ "Linda Hazzard: The “Starvation Doctor”" Archived 1 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ Nash, Jay R. (1982). Zanies: The World's Greatest Eccentrics. New Century Publishers. p. 339. ISBN 978-0832901232

- ^ a b Gratzer, Walter. (2005). Terrors of the Table: The Curious History of Nutrition. Oxford University Press. p. 201. ISBN 0-19-280661-0

- ^ Kang, Lydia; Pedersen, Nate. (2017). Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything. Workman Publishing. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-7611-8981-7

- ^ Fishbein, Morris. (1932). Fads and Quackery in Healing: An Analysis of the Foibles of the Healing Cults. New York: Covici Friede. p. 253

- ^ “セレブのビューティ会談でミランダが告白した「ちょいグロ美容法」”. spur (2017年6月13日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ “ミランダ・カーの美顔法が怖すぎ!「ヒルに顔面の血を吸わせているの」”. asajo (2017年6月23日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ “祝・50歳! グウィネス・パルトロウのエクストリームな美容ヒストリー【セレブ美容探偵】”. vogue (2022年10月13日). 2023年6月18日閲覧。

- ^ “The Science of Cupping”. nccaom.org. 2019年2月24日閲覧。

- ^ “What Is Cupping Therapy? Uses, Benefits, Side Effects, and More”. WebMD. 2019年2月24日閲覧。

- ^ “Acupuncture Odds and Ends”. Science-Based Medicine (2014年12月24日). 2016年8月8日閲覧。

- ^ “Cupping for the Cure”. Skeptoid (2013年4月23日). 2023年5月31日閲覧。

- ^ Daly, Annie (2018年6月26日). “What Is Cupping Therapy—And Should You Try It?”. Women's Health. 2019年2月24日閲覧。

- ^ Salzberg, Steven (2019年5月13日). “The Ridiculous And Possibly Harmful Practice of Cupping”. Forbes. 2019年5月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h “医療界は無関心?!”血液クレンジング”をめぐる議論”. NHK (2019年11月10日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ “芸能人が拡散する「血液クレンジング」に批判殺到 「ニセ医学」「誇大宣伝」指摘も”. buzzfeed (2019年10月22日). 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ "Suffocating Trends: Oxygen Bars and Drinks." LiveScience (2006): 1. 25 June 2009. http://www.livescience.com/health/060418_bad_oxygen.html

- ^ “The Rise of Oxygen Bars”. webMD. 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e Bren, Linda (November 2002). “Oxygen Bars: Is a Breath of Fresh Air Worth It?”. FDA Consumer (U.S. Food and Drug Administration (in FDA Consumer magazine)) 36 (6): 9–11. PMID 12523293 2018年3月14日閲覧。.

- ^ Patel, Dharmeshkumar N; Goel, Ashish; Agarwal, SB; Garg, Praveenkumar; Lakhani, Krishna K (July 2003). “Oxygen toxicity”. Journal, Indian Academy of Clinical Medicine 4 (3): 234–37.

- ^ Chavis, Vicki F., "Oxygen Bars – Health Benefit or Hazard." Natural Medicine 9 Apr. 2009: 2

- ^ Sorgen, Carol. "The Rise of Oxygen Bars." WebMD (2002):1–2. http://www.webmd.com/balance/features/rise-of-oxygen-bars

- ^ a b c “浄化行動 / パージング”. 厚生労働省. 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b Castillo, Marigold; Weiselberg, Eric (2017-04-01). “Bulimia Nervosa/Purging Disorder” (英語). Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 47 (4): 85–94. doi:10.1016/j.cppeds.2017.02.004. ISSN 1538-5442. PMID 28532966.

- ^ Sattar, Husain A. (2011). Fundamentals of Pathology. Pathoma, LLC. ISBN 9780983224600

- ^ “What Causes Vomiting?” (英語). Healthline (2014年5月13日). 2022年4月25日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “道端ジェシカさんがハマっていた“カエル毒”治療。怪しいスピに傾倒するセレブの謎”. 日刊SPA!(黒猫ドラネコ) (2023年4月6日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b “MDMAで逮捕の道端ジェシカ容疑者「カエルの毒でデトックス」「嘔吐シーン」の不可思議な近況”. NEWSポストセブン (2023年3月21日). 2023年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ “あの女優も体験した? 壮絶すぎる‘浄化の儀式’をヨガトラベラー・土屋愛が悶絶から効果まで完パケ動画配信!”. prtimes (2020年1月30日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ ““Kambô” frog (Phyllomedusa bicolor): use in folk medicine and potential health risks”. Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical - SBMT. 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ Nesterenko VB, Nesterenko AV, Babenko VI, Yerkovich TV, Babenko IV (2004-01). “Reducing the 137Cs-load in the organism of "Chernobyl" children with apple-pectin”. Swiss Med Wkly 134 (1-2): 24–7. PMID 14745664. 日本語解説

- ^ a b Cesium-137 pectin's potential remedial role is an open question IRSN 2005年 閲覧日2020年9月1日

- ^ a b c 菊池誠、松永和紀、伊勢田哲治、平川秀幸、片瀬久美子、飯田泰之:編、SYNODOS:編『もうダマされないための「科学」講義』光文社、2011年9月16日。ISBN 978-4334036447。

- ^ 「健康食品で解毒」を信じてはいけない FOOCOM.NET(2011年7月9日)

- ^ Le Gall B, Taran F, Renault D, Wilk JC, Ansoborlo E (2006-11). “Comparison of Prussian blue and apple-pectin efficacy on 137Cs decorporation in rats”. Biochimie 88 (11): 1837–41. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2006.09.010. PMID 17069947.

- ^ Kim MJ, Hwang JH, Ko HJ, Na HB, Kim JH (2015-05). “Lemon detox diet reduced body fat, insulin resistance, and serum hs-CRP level without hematological changes in overweight Korean women”. Nutr Res 35 (5): 409–20. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2015.04.001. PMID 25912765.

- ^ a b Jeffrey A. Morrison, Anita L. Iannucci (2012-04). “Symptom Relief and Weight Loss From Adherence to a Meal Replacement–enhanced, Low-calorie Detoxification Diet”. Integrative Medicine 11 (2): 42–47.

- ^ Kim JA, Kim JY, Kang SW (September 2016). “Effects of the Dietary Detoxification Program on Serum γ-glutamyltransferase, Anthropometric Data and Metabolic Biomarkers in Adults”. J Lifestyle Med 6 (2): 49–57. doi:10.15280/jlm.2016.6.2.49. PMC 5115202. PMID 27924283.

- ^ a b c Jung SJ, Kim WL, Park BH, Lee SO, Chae SW (2020). “Effect of toxic trace element detoxification, body fat reduction following four-week intake of the Wellnessup diet: a three-arm, randomized clinical trial”. Nutr Metab (Lond) 17: 47. doi:10.1186/s12986-020-00465-9. PMC 7310262. PMID 32582363.

- ^ “To evaluate detoxification and body fat mass decrease effect and safety of Wellnessup® diet: 4-weeks, Clinical trial”. cris (2018年5月18日). 2023年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ Li YF, Dong Z, Chen C, Li B, Gao Y, Qu L, Wang T, Fu X, Zhao Y, Chai Z (2012-08). “Organic selenium supplementation increases mercury excretion and decreases oxidative damage in long-term mercury-exposed residents from Wanshan, China”. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46 (20): 11313–8. doi:10.1021/es302241v. PMID 23033886.

- ^ Seppänen K, Kantola M, Laatikainen R, Nyyssönen K, Valkonen VP, Kaarlöpp V, Salonen JT (2000-06). “Effect of supplementation with organic selenium on mercury status as measured by mercury in pubic hair”. J Trace Elem Med Biol 14 (2): 84–7. doi:10.1016/S0946-672X(00)80035-8. PMID 10941718.

- ^ 苅田香苗, 坂本峰至, 吉田稔, 龍田希, 仲井邦彦, 岩井美幸, 岩田豊人, 前田恵理, 柳沼梢, 佐藤洋, 村田勝敬「メチル水銀,水銀およびセレンに関する研究動向」『日本衛生学雑誌』第71巻第3号、日本衛生学会、2016年、236-251頁、CRID 1390282681338628736、doi:10.1265/jjh.71.236、ISSN 0021-5082、PMID 27725427、2023年8月24日閲覧。

- ^ “平成 26 年度水俣病に関する総合的研究 メチル水銀曝露による健康影響に関するレビュー” (PDF). 2023年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b 樺島順一郎, 植松洋子, 荻本真美「ミネラル補給用サプリメントの含有量調査:セレンの分析」(PDF)『東京都健康安全研究センター研究年報』第58号、東京都健康安全研究センター、2007年、189-193頁、CRID 1521417756163197312、ISSN 13489046、2023年8月24日閲覧。

- ^ “魚介類・鯨類の水銀についてのQ&A”. 日本生活協同組合連合会. 2023年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ Zhao ZY, Liang L, Fan X, Yu Z, Hotchkiss AT, Wilk BJ, Eliaz I (2008). “The role of modified citrus pectin as an effective chelator of lead in children hospitalized with toxic lead levels”. Altern Ther Health Med 14 (4): 34–8. PMID 18616067.

- ^ Jandacek RJ, Heubi JE, Buckley DD, Khoury JC, Turner WE, Sjödin A, Olson JR, Shelton C, Helms K, Bailey TD, Carter S, Tso P, Pavuk M (2014-04). “Reduction of the body burden of PCBs and DDE by dietary intervention in a randomized trial”. J. Nutr. Biochem. 25 (4): 483–8. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2014.01.002. PMC 3960503. PMID 24629911.

- ^ “FDA Changes Labeling Requirement for Olestra”. FDA (2003年8月1日). 2023年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Everything you wanted to know about Olestra”. healthyandhot (2007年8月23日). 2023年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ “○「健康食品」に係る虚偽・誇大広告等の禁止”. 厚生労働省. 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ “消費者庁がインターネットにおける健康食品等の虚偽・誇大表示の改善を要請”. 国立健康・栄養研究所 (2022年3月11日). 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ a b “The Detoxification Myth”. skeptoid (2008年1月15日). 2023年6月6日閲覧。

- ^ a b 'Detox diet' woman awarded £810,000 Express、2008年7月23日

- ^ “The detox myth: Why you should stop wasting money on juices” (英語). Metro (2014年3月24日). 2020年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ David Gorski (2011年5月23日). “Fashionably toxic”. Science-Based Medicine. 2019年1月30日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年1月29日閲覧。

- ^ “TheTruth About... Detox Diets” (PDF). NHS. 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Scientists dismiss 'detox myth'”. (2009年1月5日) 2020-05-27-GB閲覧。

- ^ Randerson, James; correspondent, science (2009年1月5日). “Detox remedies are a waste of money, say scientists”. The Guardian 2020年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ Hale, Beth. “Detox diets to kick-start the New Year are a 'total waste of money' say experts”. Mail Online. 2020年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Products offering an easy detox 'are a waste of time'”. The Independent (2009年1月5日). 2020年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “「デトックス」製品は無意味?英科学者団体が指摘”. www.afpbb.com. 2020年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b “「スティーブ・ジョブズは治療可能な病で死亡した」世界一の大富豪が手術よりコーヒー浣腸を選んだワケ”. PRESIDENT(左巻健男) (2022年10月11日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ “スティーブ・ジョブズの命を奪った病。彼はなぜ早期手術を拒んだのか?”. Forbes (2020年2月4日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ 南出賢一 (2021年7月4日). “#10 未成年者へのワクチン接種は反対です”. 2021年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ 南出賢一 (2021年5月13日). “#8何が大義ですか?”. 2021年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ 南出賢一 (2021年5月9日). “#7全国的な議論にすべきだと思う、新たなコロナ対策”. 2021年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ a b “大阪府泉大津市 - 新型コロナ後遺症・ワクチン副反応で悩んでいる方を救いたい!改善プログラムを展開!”. ふるさと納税クラウドファンディング. 2022年12月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b “泉大津市×新型コロナウイルスに係るリビングラボ事業”. 公益資本主義株式会社トップフェローズ. 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ “ふるさと納税型クラウドファンディングで社会課題の解決へ!(令和4年11月25日)”. 泉大津市 (2022年11月29日). 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ “泉大津から始まる「新しい健康づくり」。健康状態の見える化と養生ステーション開設!”. ふるさと納税クラウドファンディング. 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ “南出市長とファスティング‼︎”. ゆりや化粧品店 (2022年2月4日). 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ “昔の人が言うことは、なるほどです”. ゆりや化粧品店 (2022年2月14日). 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ “「GRカフェ@泉大津」開催”. ヘルスベース泉大津 (2021年6月8日). 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ “イベントの記事一覧”. ヘルスベース泉大津. 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Scientology does detox”. newsreview (2007年2月22日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b Dougherty, Geoff (1999年3月28日). “Store selling Scientology vitamin regimen raises concerns”. St. Petersburg Times. 2009年2月14日閲覧。

- ^ DeSio, John (2007年5月30日). “The Rundown on Scientology's Purification Rundown”. New York Press. 2007年6月1日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年1月20日閲覧。

- ^ Kelsey, Tim; Mike Ricks (1994年1月31日). “The Prisoners of Saint Hill”. The Independent: p. (II) 1. オリジナルの2009年11月30日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2009年2月17日閲覧。

- ^ a b Al-Zaki, Taleb; B Tilman Jolly (January 1997). “Severe Hyponatremia After Purification”. Annals of Emergency Medicine (Mosby, Inc.) 29 (1): 194–195. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(97)70335-4. PMID 8998113.

- ^ O'Donnell, Michelle (2003年10月4日). “Scientologist's Treatments Lure Firefighters”. The New York Times. オリジナルの2013年5月24日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2006年9月17日閲覧。

- ^ Roberton, Craig (1981年12月28日). “Narconon”. St. Petersburg Times: pp. 1–B 2009年2月21日閲覧。

- ^ “Cruise lobbies over Scientology”. (2002年1月30日)

- ^ Weisman, Aly (2015年10月27日). “19 famous Church of Scientology members”. Business Insider. 2016年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b DeSio, John (2007年5月31日). “The Rundown on Scientology's Purification Rundown: What Scientologists aren't telling you about their detox program (and how much it's costing you)”. New York Press

- ^ "Interview With Tom Cruise". Larry King Live. 28 November 2003. CNN。

- ^ Scientologist's Treatments Lure Firefighters, Michelle O'Donnell, NY Times, October 4, 2003

- ^ Friedman, Roger (2006年12月22日). “Tom Cruise Can't Put Out These Fires”. FOX 411 (Fox News Channel) 2006年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ a b Crouch, Edmund A. C.; Laura C. Green (October 2007). “Comment on "Persistent organic pollutants in 9/11 world trade center rescue workers: Reduction following detoxification" by James Dahlgren, Marie Cecchini, Harpreet Takhar, and Olaf Paepke [Chemosphere 69/8 (2007) 1320–1325]”. Chemosphere 69 (8): 1330–1332. Bibcode: 2007Chmsp..69.1330C. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.05.098. PMID 17692360.

- ^ “農薬を減らし健やかで安全な世界へ”. デトックス・プロジェクト・ジャパン. 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ “無責任な代議士たちのラウンドアップ批判”. 農業技術通信社 (2019年8月30日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b “元農林水産大臣 山田正彦さんからのメッセージをUp。”. 衆議院議員 こみやま泰子 (2021年10月22日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “怪しさ満点「デトックス・プロジェクト・ジャパン」イベント潜入記”. agrifact (2021年7月20日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ “Data on Toxins”. Moms Across America. 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ “CBS Los Angeles Discusses GMOs With Anti-Vaxxer Zen Honeycutt”. THE AMERICAN COUNCIL ON SCIENCE AND HEALTH (2020年1月30日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ “わたしたちのごはんの未来 山田正彦さん講演会”. Table(タブル)コープ自然派事業連合 (2020年1月14日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ “ゼン・ハニーカットさん全国ツアー「アメリカを変えたママに聞く食の未来」”. Table(タブル)コープ自然派事業連合 (2020年2月20日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e “公開討論会「食の信頼向上をめざして〜食品安全委員会、消費者委員会のこれから」”. くらしとバイオプラザ21 (2009年10月6日). 2023年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b “「量」について考えよう” (PDF). 食品安全委員会. 2023年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d “~食品の安全性とリスク分析~”. 食品安全委員会 (2014年11月26日). 2023年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “食の安全はどのように守られているか”. 食品分析開発センター(SUNATEC). 2023年6月9日閲覧。

- ^ “食塩の致死量”. 塩ナビ (2021年1月19日). 2023年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b “用語集検索(リスク評価)”. 食品安全委員会. 2023年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ “食品関係用語集”. 厚生労働省. 2023年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “日本食品添加物協会”. 日本食品添加物協会. 2020年6月25日閲覧。

- ^ “「ADI」と「TDI」” (PDF). 食品安全委員会. 2023年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ “食品安全の基礎知識と 食品添加物について” (PDF). 食品安全委員会 (2018年6月20日). 2023年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ “一日摂取許容量(ADI)とは? 残留基準値(0.01ppm)の6倍ものメタミドホスが検出されたお米を、 食べても大丈夫と言えるのはなぜ?” (PDF). 食品安全委員会. 2023年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ Baggini, Julian (2004). Making Sense: Philosophy Behind the Headlines. Oxford University Press. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-0-19-280506-5

- ^ Meier, Brian P.; Dillard, Amanda J.; Lappas, Courtney M. (2019). “Naturally better? A review of the natural-is-better bias” (英語). Social and Personality Psychology Compass 13 (8): e12494. doi:10.1111/spc3.12494. ISSN 1751-9004.

- ^ “天然・自然のものなら安心?” (PDF). 厚生労働省. 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ “ビワの種 アミグダリン体内で分解されると青酸 粉末食品食べないで”. NHK (2023年2月17日). 2023年6月14日閲覧。

- ^ a b c 松川哲也、梶山慎一郎「天然物由来成分に騙されるな : 天然物は本当に安全なの?(続・生物工学基礎講座-バイオよもやま話-)」『生物工学会誌』第92巻第10号、日本生物工学会、2014年、556-559頁、CRID 1520009408714930816、ISSN 09193758、NDLJP:10519003。

- ^ 左巻健男『学校に入り込むニセ科学』平凡社、2019年11月18日。ISBN 978-4582859256。

- ^ a b c d e f “今さら聞けないインフルエンザの予防接種の話~ワクチンの効果と、よくある誤解”. お薬Q&A〜Fizz Drug Information〜 (2021年7月19日). 2022年9月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Vaccine Safety & Availability - Thimerosal and Vaccines”. FDA. 2019年3月6日閲覧。

- ^ “Thimerosal in vaccines”. Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2008年6月3日). 2008年7月26日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年7月25日閲覧。

- ^ Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (2019-04-05). “Thimerosal and Vaccines”. FDA (fda.gov).

- ^ ハイジ・J・ラーソン『ワクチンの噂 どう広まり、なぜいつまでも消えないのか』みすず書房、2021年。ISBN 978-4-622-09052-6。

- ^ a b “調査結果報告書” (PDF). 独立行政法人 医薬品医療機器総合機構(PMDA) (2009年10月16日). 2022年10月29日閲覧。

- ^ Paul Offit. “Thimerosal and vaccines – a cautionary tale”. The New England Journal of Medicine 357 (13): 1278–79. doi:10.1056/NEJMp078187. PMID 17898096.

- ^ “水銀・メチル水銀の暫定耐容一週間摂取量(PTWI)”. 農林水産省. 2022年9月18日閲覧。

- ^ Bose-O'Reilly S, McCarty KM, Steckling N, Lettmeier B. “Mercury exposure and children's health”. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 40 (8): 186–215. doi:10.1016/j.cppeds.2010.07.002. PMC 3096006. PMID 20816346.

- ^ “チメロサールを含む国有ワクチン” (PDF). 北海道薬剤師会. 2022年10月29日閲覧。

- ^ a b “妊婦への魚介類の摂食と水銀に関する注意事項” (PDF). 農林水産省. 2022年12月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b 岩田健太郎『ワクチンは怖くない』光文社、2017年。ISBN 978-4334039653。

- ^ “Vaccines are not associated with autism: an evidence-based meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies”. Vaccine . 2014 Jun 17;32(29):3623-9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.085. (2014年5月9日). 2023年6月25日閲覧。

- ^ “The Doctor Who Fooled The World: An excerpt from Brian Deer’s new book about Andrew Wakefield”. Retraction Watch. 2022年9月20日閲覧。

- ^ “How campaigners and the media push bad science”. BMJ (2011年1月18日). 2022年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ ポール オフィット (著)、ナカイ サヤカ (翻訳)『反ワクチン運動の真実: 死に至る選択』地人書館、2018年。ISBN 978-4805209219。

- ^ “過去50年間で最大の「科学的不正」とは?”. gizmodo (2020年12月27日). 2022年9月24日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Principi, N; Esposito, S. “Aluminum in vaccines: Does it create a safety problem?”. Vaccine 36 (39): 5825–31. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.08.036. PMID 30139653.

- ^ a b Baylor NW, Egan W, Richman P. “Aluminum salts in vaccines – US perspective”. Vaccine 20 Suppl 3: S18–23. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00166-4. PMID 12184360.

- ^ Leslie M. “Solution to vaccine mystery starts to crystallize”. Science 341 (6141): 26–27. doi:10.1126/science.341.6141.26. PMID 23828925.

- ^ a b François G, Duclos P, Margolis H, Lavanchy D, Siegrist CA, Meheus A, Lambert PH, Emiroğlu N, Badur S, Van Damme P. “Vaccine safety controversies and the future of vaccination programs”. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 24 (11): 953–61. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000183853.16113.a6. PMID 16282928.

- ^ “HPVワクチンの安全性に関する声明” (PDF). 厚生労働省 (2014年3月12日). 2022年9月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Vaccine ingredients”. University of Oxford (2022年5月26日). 2022年9月18日閲覧。

- ^ Mitkus RJ, King DB, Hess MA, Forshee RA, Walderhaug MO. “Updated aluminum pharmacokinetics following infant exposures through diet and vaccination”. Vaccine 29 (51): 9538–43. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.124. PMID 22001122.

- ^ “Common Ingredients in U.S. Licensed Vaccines”. CDC (2019年4月19日). 2022年9月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Adjuvants and Vaccines”. CDC (2020年8月14日). 2022年9月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “The “Mercury Toxicity” Scam: How Anti-Amalgamists Swindle People”. Quackwatch (2006年3月2日). 2023年6月6日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “【Q&A】昔治療したアマルガム修復物・銀歯はとったほうがよい?”. NHK (2020年3月9日). 2023年6月9日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d “歯科用アマルガム(に含まれる水銀)に関する Q & A 集” (PDF). 日本歯科保存学会. 2023年6月9日閲覧。

- ^ “WHO Consensus Statement on Dental Amalgam”. FDI. 2015年6月13日閲覧。[リンク切れ]

- ^ “Safety of Dental Amalgam”. American Dental Association. 2015年6月13日閲覧。

- ^ “In the dentist's chair”. British Homeopathic Association (2013年6月13日). 2015年6月12日閲覧。

- ^ “How safe are Amalgam / Mercury fillings?”. Irish Dental Association. 2015年6月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Patient Information on Dental Amalgam”. Irishealth.com. 2015年6月13日閲覧。[リンク切れ]

- ^ “Amalgames dentaires”. Association Dentaire Française. 2015年6月12日閲覧。

- ^ “歯科医療について(その2)” (PDF). 厚生労働省 中央社会保険医療協議会 (2015年11月20日). 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ “歯科用アマルガム使用に関する見解について” (PDF). 日本歯科医師会 (2013年9月11日). 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “新型コロナウイルスとともにさらに広がるニセ科学”. 論座(朝日新聞社) (2020年5月8日). 2023年6月9日閲覧。

- ^ 傳田光洋『皮膚は考える』岩波書店、2005年11月3日。ISBN 978-4000074520。

- ^ a b “「他社の商品を攻撃して自社商品を売る」“危険です商法””. 日本石鹸洗剤工業会 (JSDA) (2010年9月21日). 2023年5月31日閲覧。

- ^ “特定商取引法違反の連鎖販売業者に対する 業務停止命令について” (PDF). 経済産業省 (2008年2月20日). 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ “健康食品の正しい利用法” (PDF). 厚生労働省. 2023年6月2日閲覧。

- ^ “トンデモ健康法の理論的背景は酵素にあった!〜酵素信仰はニセ医学のはじまり(1)”. 五本木クリニック (2021年4月17日). 2023年5月28日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h “「免疫力」という言葉が不適切な理由…「トンデモ」健康情報に踊らされないために”. Yahoo! (峰宗太郎) (2020年7月7日). 2023年6月8日閲覧。

- ^ a b “新型コロナ予防に乳酸菌は効くか?エビデンスを見極める(前編)”. Wedge (2020年5月21日). 2023年6月8日閲覧。

- ^ “免疫力を上げる方法はない?誤解の多い「免疫」について、医師が解説!”. ミモレ(山田悠史) (2023年2月10日). 2023年6月9日閲覧。

- ^ “最新免疫学から分かってきた新型コロナウイルスの正体―宮坂昌之・大阪大学名誉教授”. 科学技術振興機構 (2020年12月25日). 2023年6月9日閲覧。

- ^ “今起こっている『免疫力低下』とは、どういう意味ですか?”. Yahoo!(堀向健太) (2023年6月8日). 2023年6月14日閲覧。

- ^ a b “論文紹介:序列と免疫反応(似非科学への落とし穴)”. Yahoo!(西川伸一) (2016年11月27日). 2023年6月8日閲覧。

- ^ “免疫力はワクチン接種以外でも上げられますか。”. 厚生労働省. 2023年6月9日閲覧。

- ^ “ためしてガッテン:500回記念!徹底検証・血液サラサラの真実”. NHK (2006年8月30日). 2023年6月4日閲覧。

- ^ “医師等の免許を持たない者が検査を行い、商品等を契約させる手口に注意!(報道発表資料)”. 国民生活センター (2007年3月7日). 2023年6月12日閲覧。

- ^ “『ドロドロ血』と違法診察 千代田区の医療会社捜索 サービス勧誘目的?”. 東京新聞 (2007年6月12日). 2023年6月12日閲覧。

- ^ “血液サラサラは顕微鏡で細工、元営業マンが商法を暴露”. 読売新聞 (2007年6月29日). 2023年6月12日閲覧。

- ^ “ブレスレット詐欺:「血液さらさら」と偽り販売、社長逮捕”. 毎日新聞 (2007年11月6日). 2023年6月12日閲覧。

- ^ 中村宜督『食品でひく 機能性成分の事典』女子栄養大学出版部、2022年7月28日。ISBN 978-4789509268。

- ^ “脳卒中を発症した人に対する抗凝固薬による早期治療”. コクラン (2021年10月22日). 2023年6月8日閲覧。

- ^ “脳出血の意外なリスク(抗血栓薬・アミロイド)や治療”. NHK (2022年8月8日). 2023年6月8日閲覧。

- ^ “出血リスクの評価と抗血栓薬による出血”. 日経メディカル (2022年11月21日). 2023年6月8日閲覧。

- ^ “健康食品に関する景品表示法及び健康増進法上の留意事項について” (PDF). 消費者、 (2016年6月30日). 2021年7月23日閲覧。

- ^ “医薬品的な効能効果について”. 東京都健康福祉局. 2021年7月23日閲覧。

- ^ “「血液サラサラ」宣伝は景品表示法違反 沖縄特産販売の健康食品 総合事務局が措置命令”. 琉球新報 (2022年6月2日). 2023年6月8日閲覧。

- ^ “第13回 デトックスという物語、毒出しという疑似科学【分断をこえてゆけ 有機と慣行の向こう側】”. agrifact (2021年9月20日). 2023年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ “発達障害を食事やミネラルで改善しましょうというお話には気をつけて”. Yahoo!(成田崇信) (2018年1月21日). 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ Sapp, Sarah G. H.; Bradbury, Richard S.; Bishop, Henry S.; Montgomery, Susan P. (March 2019). “Regarding: A Common Source Outbreak of Anisakidosis in the United States and Postexposure Prophylaxis of Family Collaterals”. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 100 (3): 762. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.18-1019. ISSN 0002-9637. PMC 6402927. PMID 30843503.

- ^ Tabbalat, Rinad Ramzi; Cal, Nicolas Vital; Mayigegowda, Kavya Kelagere; Desilets, David John (August 2019). “Two Cases of Gastrointestinal Delusional Parasitosis Presenting as Folie á Deux”. ACG Case Reports Journal 6 (8): e00183. doi:10.14309/crj.0000000000000183. ISSN 2326-3253. PMC 6791610. PMID 31737714.

- ^ a b Harriet Hall (2014年5月27日). “Rope Worms: C'est la Merde” (英語). Science-Based Medicine. 2019年1月9日閲覧。

- ^ William Parker (2015年5月6日). “Helminths: ASD Cause or Potential Treatment”. Autism Research Institute. 2019年2月14日閲覧。

- ^ Barrett, S. (1985). “Commercial hair analysis. Science or scam?”. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 254 (8): 1041–1045. doi:10.1001/jama.254.8.1041. PMID 4021042.

- ^ Seidel, S. (2001). “Assessment of Commercial Laboratories Performing Hair Mineral Analysis”. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 285 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1001/jama.285.1.67. PMID 11150111.

- ^ Hair analysis: A potential for medical abuse. Policy number H-175.995,(Sub. Res. 67, I-84; Reaffirmed by CLRPD Rep. 3 – I-94)

- ^ Hart, Katherine (2018). “4.6 Fad diets and fasting for weight loss in obesity.”. In Hankey, Catherine (英語). Advanced nutrition and dietetics in obesity. Wiley. pp. 177–182. ISBN 9780470670767

- ^ a b Hankey, Catherine (2017-11-23) (英語). Advanced Nutrition and Dietetics in Obesity. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 179–181. ISBN 9781118857977

- ^ a b Whitney, Eleanor Noss; Rolfes, Sharon Rady; Crowe, Tim; Walsh, Adam. (2019). Understanding Nutrition. Cengage Learning Australia. pp. 321-325. ISBN 9780170424431

- ^ “Fact Sheet – Fad diets”. British Dietetic Association (2014年). 2015年12月12日閲覧。 “Fad-diets can be tempting as they offer a quick-fix to a long-term problem.”

- ^ Kraig, Bruce (2013). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 623–626. ISBN 9780199734962

- ^ a b “Fact Sheet – Fad diets”. British Dietetic Association (2014年). 2015年12月12日閲覧。 “Fad-diets can be tempting as they offer a quick-fix to a long-term problem.”

- ^ Flynn MAT (2004). Gibney MJ. ed. Chapter 14: Fear of Fatness and Fad Slimming Diets. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 236–246. ISBN 978-1-118-69332-2

- ^ Fitzgerald M (2014). Diet Cults: The Surprising Fallacy at the Core of Nutrition Fads and a Guide to Healthy Eating for the Rest of US. Pegasus Books. ISBN 978-1-60598-560-2

- ^ Williams, William F. (2013-12-02) (英語). Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience: From Alien Abductions to Zone Therapy. Routledge. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9781135955229

- ^ Rowe, Aaron (2008-03-17). “Video: Hexagonal Water is an Appalling Scam”. Wired 2011年10月18日閲覧。.

- ^ “Drinking Water and Water Treatment Scams”. Alabama Cooperative Extension System (2003年10月22日). 2023年7月11日閲覧。[リンク切れ]

- ^ “Understanding Hexagonal Water”. Aqua Technology. 2011年10月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Hexagonal Water”. Frequency Rising. 2011年10月18日閲覧。

- ^ “恐ろしげな化学物質「ジハイドロゲンモノオキサイド」の正体とは?”. ダイヤモンド社 (2021年3月6日). 2023年6月9日閲覧。

- ^ “The Pseudoscience of Ear Wax Removal”. Skeptical Inquirer 22 (6): 17. (1998).

- ^ Seely, D.R.; Quigley, S.M.; Langman, A.W. (1996). “Ear candles: Efficacy and safety”. Laryngoscope 106 (10): 1226–1229. doi:10.1097/00005537-199610000-00010. PMID 8849790.

- ^ “Ear Candling: Is it Safe?”. MayoClinic.org. Mayo Clinic. 2014年6月7日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Oil Pulling Your Leg”. Science-Based Medicine (2014年3月12日). 2017年4月22日閲覧。

- ^ King A (13 April 2018). “Bad science: Oil pulling”. British Dental Journal 224 (7): 470. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.281. PMID 29651060.

- ^ “Oil Pulling Your Leg”. Science Based Medicine (2014年3月12日). 2017年4月22日閲覧。

- ^ “Effect of oil pulling in promoting oro dental hygiene: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials”. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 26: 47–54. (June 2016). doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2016.02.011. PMID 27261981.

- ^ Lakshmi, T; Rajendran, R; Krishnan, Vidya (2013). “Perspectives of oil pulling therapy in dental practice”. Dental Hypotheses 4 (4): 131–134. doi:10.4103/2155-8213.122675.

- ^ “Lipids in preventive dentistry”. Clinical Oral Investigations 17 (3): 669–685. (April 2013). doi:10.1007/s00784-012-0835-9. PMID 23053698.

- ^ “Oil Pulling”. American Dental Association. 2023年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ Anna Lazowski (2014年6月5日). “Oil pulling: Ancient practice now a modern trend”. CBC News. 2014年6月10日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “α-リポ酸”. 国立健康・栄養研究所 (2021年1月29日). 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ a b “α-リポ酸” (PDF). 北海道薬剤師会. 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- ^ “α-リポ酸に関するQ&A”. 厚生労働省. 2023年5月29日閲覧。

- デトックスのページへのリンク