サーンチー

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2024/03/24 05:51 UTC 版)

サータヴァーハナ時代(紀元前1世紀 - 紀元1世紀頃)

サタカルニ2世率いるサータヴァーハナ帝国はシュンガ国からマールワー東部を奪った[56]。これにより、サータヴァーハナ王家はサーンチーの仏教遺跡を手に入れ、装飾された門を、元々のマウリヤ帝国とシュンガ国の仏塔の周囲に建設したとされている[57]。紀元前1世紀から、高度に装飾された門が造られはじめ、欄干や門にも色が付けられた[23]。門は紀元1世紀頃まで造られ続けた[43]。

ブラーフミー文字のシリ - サタカニ碑文には、南門上部のアーキトレーブの一つがサータヴァーハナ王サタカルニ (2世)の工匠によって贈られたことが記録されている[54]。

𑀭𑀸𑀜𑁄 𑀲𑀺𑀭𑀺 𑀲𑀸𑀢𑀓𑀡𑀺𑀲 (Rāño Siri Sātakaṇisa)

𑀆𑀯𑁂𑀲𑀡𑀺𑀲 𑀯𑀸𑀲𑀺𑀣𑀻𑀧𑀼𑀢𑀲 (āvesaṇisa vāsitḥīputasa)

𑀆𑀦𑀁𑀤𑀲 𑀤𑀸𑀦𑀁 (Ānaṁdasa dānaṁ)「ラージャン (王)・シリ・サータカニの工匠の長 ヴァシティの息子である、アーナンダからの贈り物」

サタカルニの日付と身元については、いくつか不確実なところがあり研究者の間で議論されている。その理由は、ハティグンパ碑文にサタカルニ王が載っているが、この碑文はもっと古い紀元前2世紀のものとされることがあるからである。また、何人かのサータヴァーハナ王が「サタカルニ」という名前を使ったことも問題をより複雑にしている。通常、門の年代は紀元前50年から紀元1世紀までとされており、最も初期の門の建設者は、紀元前50年 - 25年に統治したサタカルニ2世であると一般には考えられている[56][43]。

もう一つの初期のサータヴァーハナの遺跡として、ネイシク洞窟にあるカンハ王(紀元前100年 - 70年)の洞窟No.19が知られているが、これはサーンチーのトーラナ(門)よりも芸術的な発達の程度がはるかに低い。

浮彫りのテーマ

ジャータカ(本生譚)

西門を中心に、以下のようなジャータカが描かれている。ジャータカは、仏教の道徳的な物語であり、仏陀が前世でまだ菩薩であったときの啓発的な出来事を語っている。

- スヤマ・ジャータカ(仏陀が前世で、目の見えない隠者の夫婦の息子であったときの孝行物語)

- ヴェッサンタラ・ジャータカ(仏陀が前世で、無欲で妻子まで布施してしまう王子であったときの物語)

- マハーカピ・ジャータカ(仏陀が前世で、偉大な猿の王であったときの物語)

奇跡

仏陀の奇跡が数多く記されている。

降魔成道

悪魔マーラが仏陀の悟りを邪魔しようと送り込んだ魅惑的な娘たちやその軍勢に、仏陀が立ち向かう場面が数多くある。マーラの誘惑をくだし(降魔)、仏陀は悟りを開いた。

仏舎利をめぐる戦い

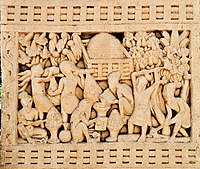

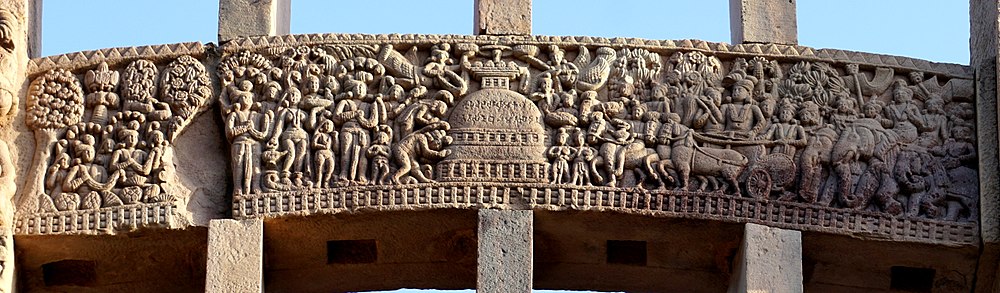

第一塔の南門は、仏塔の正門であり最古のものであると考えられており[61]、そこには仏舎利の物語がいくつも描かれている。その物語は仏舎利をめぐる戦いから始まる。仏陀の入滅後、クシナガラのマッラ族は仏陀の遺骨を持ち続けたいと考えたが、他の王国も自分たちの取り分を求め、戦いを起こしてクシナガラの街を包囲した。最終的には合意に達し、仏舎利は8つの王族に分配された[62][63]。この有名な光景は、サータヴァハナ朝時代の戦争技術だけでなく、マッラ国のクシナガラ市の眺めを示しており、古代インドの都市を理解する上で頼りになっている。

アショーカによる仏舎利の移転

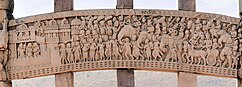

仏教徒の伝説によると、数世紀後、アショーカ王は仏舎利をそれまで護ってきた8つの王国から移転して、84,000の仏塔に祀ろうとした[62][66][67]。アショーカは7つの王国からは仏舎利を入手したが、ラーマグラマのナーガ族は強すぎて、そこから仏舎利を奪うことはできなかった。この場面は、サーンチーの第一塔の南門の横断部分に描かれている。アショーカ王は戦車に乗り右側の軍隊の中に示され、仏舎利のある仏塔が中央に、蛇の頭をもつナーガの王たちが左端の木々の下に描かれている[68]。

アショーカ王によるブッダガヤ大菩提寺の建築

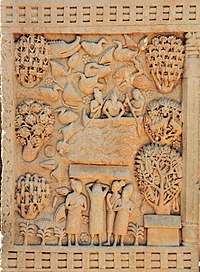

アショーカ王は、十四章摩崖法勅の第八章[72]に記載されているように、ブッダがその下で悟りを開いた菩提樹を訪ねるためにブッダガヤに行った。しかし、アショカ王は、聖なる菩提樹が適切に手入れされておらず、ティシャラクシター女王の怠慢により枯れかけていることを知り、深く悲しんだ[73]。その結果、アショカ王は菩提樹の世話に努め、その周りに寺院を建てた。この寺院がブッダガヤの中心となった。サーンチーの第一塔の南門にある彫刻には、2人の女王に支えられ悲しみに暮れるアショーカ王の姿が描かれている。そして、その上の浮彫りには新しい寺院の中で茂る菩提樹が見える。その他にもサーンチーの彫刻には、菩提樹への祈りの場面や、ブッダガヤの寺院の中の菩提樹が多く示されている[73]。

菩提樹の寺院を描いた浮彫りは他にも菩提樹の寺(東門)など、サーンチーで見ることができる。

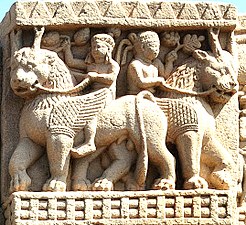

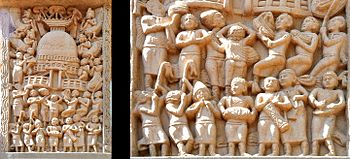

外国人信者

サーンチーのフリーズ (建築)の一部にはギリシャの衣装を着た信者も登場し、キルトのチュニックやギリシャのピレウス帽をかぶって描かれている[75][76][74]。彼らはサカ族と説明されることもあるが、この歴史時代には中央インドに存在するのが早すぎるように思われ、2つ登場するとんがり帽子がスキタイ人であるとするには短すぎるように思われる[74]。サーンチーの公式の掲示には「外国人による仏塔崇拝」と記載されている[77]。男性は短い巻き毛で描かれており、ギリシャのコインでよく見られるタイプのヘアバンドを巻いていることが多い。服装もギリシャ風で、典型的なギリシャ旅行衣装のチュニック、ケープ、サンダルを身につけている[78]。アウロスと呼ばれる「完全にギリシャ風」の二本管の木管など、楽器も非常に特徴的である[74][79]。カーニクス(英語: carnyx)という コルヌ(英語: Cornu (horn))のような金管楽器も見える[79]。

ヤヴァナ(英語: Yavanas)とかヨナ (人々)(英語: Yona)と呼ばれたギリシャの寄付者が[80]、サーンチーの建設に実際に参加していたことは3つの碑文で自ら宣言していることからわかる。

- 最も明瞭なものは "Setapathiyasa Yonasa danam"(セータパサのヨナの寄進)と読める[81][82]。セータパサがどこかは不明確であるが、ナーシクの近くと思われ[83]、そこではヤヴァナによる別の奉納が行われたことが知られている。たとえば、ナーシク洞窟(英語: Nasik Caves)群の洞窟No.17の中や、その近くのカルラ洞窟(英語: Karla Caves)の柱の上で見られる。

- 柱にある2番目の同様の碑文には、「[Sv]etapathasa (Yona?)sa danam」と書かれており、おそらく同じ意味である(セータパサのヨナの寄進)[83][84]。

- 3番目の碑文は、隣接する2つの敷石に「Cuda yo[vana]kasa bo silayo」(ヨナカのCudaの2つの敷石)と書かれている[85][83]。

近辺の外国人信者に関わる遺跡

紀元前113年頃、インド・グリーク朝の支配者アンティアルキダス(英語: Antialkidas)の大使であったヘリオドロス (インド・グリーク朝の大使)(英語: Heliodurus)が、サーンチから約8マイル離れたヴィディシャー村にヘリオドロスの柱(英語: Heliodorus pillar)を奉献したことが知られている。

バールフットにも、バールフット・ヤヴァナ(紀元前100年頃)と呼ばれるかなり似た別の外国人が描かれている。彼らもギリシャ王のようにチュニックと王室のヘアバンドを着ており、剣には仏教のトリラトナを掲げている[86][87]。またもう一つの例を、オリッサ州のウダヤギリ・カンダギリ洞窟で見ることができる。

| サーンチーに描かれた北西からの外国人 |

反偶像主義(仏陀の図像表現の忌避)

これら全ての場面において、仏陀は決して描写されない。たとえその場面で仏陀が中心的な役割を果たしていても、その姿は全く描かれない。ナイランジャナー川(尼連禅河)の上を歩く仏陀の奇跡では、仏陀は水の上の道によってのみ表現されている[90]。スッドーダナ王のカピラヴァストゥからの行列では、仏陀は行列の最後で空中を歩くが姿は描かれず、仏陀の道の象徴に向かって人々が頭を上に向けている様子だけが描かれている[90]。

カピラヴァストゥの奇跡の浮彫りの一つには、息子の仏陀が空に昇ったときにスッドーダナ王が祈る姿が描かれている。 天人たちによって称賛される仏陀自体は描かれず、その道だけがチャンクラマ (経行の道)(英語: Chankrama)または「プロムナード」と呼ばれる中空に吊り下げられた板の形で描かれる[89]。

それ以外の場合、仏陀の存在はビンビサーラが王室の随行員とともに仏陀を訪問するためにラージャグリハ市から出発する場面のように、空の玉座によって象徴される[58]。同様の場面は後になってガンダーラ美術にも登場するが、その時には仏陀が図像で表現される。ジョン・マーシャル (考古学者)は、彼の独創的な著作"A Guide to Sanchi"で全てのパネルを詳しく説明した[91]。

このような仏陀の図像の忌避は、説一切有部の律[92]から知られる、古代仏教の禁止事項に準拠している可能性がある。

「仏身の像を造ることは許されていません。そこで、私は祈り求めます、私が世尊の脇侍の菩薩像を造ることができますようにと。これは許されますか?」世尊はこう応えた「菩薩の像は造っても構わない」と。[93][94]

- ^ Buddhist Circuit in Central India: Sanchi, Satdhara, Sonari, Andher, Travel Guide. Goodearth Publications. 2010. ISBN 9789380262055.

- ^ a b c d e f g h https://frontline.thehindu.com/arts-and-culture/heritage/buddhism-in-stone/article8932251.ece, 2024年1月15日 閲覧

- ^ Buddhist Art Frontline Magazine 13–26 May 1989

- ^ a b c Marshall, "A Guide to Sanchi" p. 31

- ^ a b c 仏塔のまわりに設置される玉垣のような低い壁ないし柵で、その途中にトーラナ(門)が設置される。石柱と笠石、貫石で構成されることが多い[1]

- ^ British Museum collection

- ^ Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. p. 207. ISBN 9780195356663

- ^ 。この3文字は"-sa dānaṁ"と読むことができ、「~の寄進」という意味であることが判明した

- ^ 『佐々木閑の仏教講義 4「仏教再発見の旅 88」(「仏教哲学の世界観」第7シリーズ)』、youtube、 2021年9月29日

- ^ Indian Numismatic Studies by K. D. Bajpai p. 100、要検証

- ^ Ornament in Indian Architecture, Margaret Prosser Allen, University of Delaware Press, 1991 p. 18、要検証

- ^ John Marshall, "An Historical and Artistic Description of Sanchi", from A Guide to Sanchi, Calcutta: Superintendent, Government Printing (1918). pp. 7-29 on line, Project South Asia.Archived 10 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ SANCHI AND ITS REMAINS, General F.C.Maisey, 1892

- ^ GENERAL F.C. Maisey, SANCHI AND ITS REMAINS, Chapter II, KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO., 1882

- ^ "The construction of the mound, or Sthupa proper, is as follows : - In centre, a shaft, or , more probably, an inner mound, of brickwork ( the bricks measuring 16×10×3 inches), laid in mud, then loose stones and rubble ; and, outside, a casing of dressed stones, about eight inches thick, laid one over the other, in horizontal layers. The exterior was, once, coated with plaster, about four inches thick; portions of which I found still adhering to the building." GENERAL F.C. Maisey, SANCHI AND ITS REMAINS, Chapter III, KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO., 1882

- ^ "The Mahastupa consists of a hemispherical mound ( anda ) built over a relic chamber ( tabena ). It has a truncated and flattened top on which rests a square chamber ( harmika ), which has a railing and a central pillar ( yasthi ) supporting a stone triple-umbrella formation ( chattravali ). There are two circumambulatory passages. There is an elevated terrace ( medhi ) enclosed by a three-bar railing ( vedika ) and accessed by two flights of stairs ( sopanas ) from the southern gateway. The second circumambulatory passage is on the ground surrounding the mound ( pradakshinapath ). This whole structure has been put within a stone enclosure with a similar three-bar railing with four carved gateways ( toranas ) built in four cardinal directions. The ground balustrade ( vedika ), in turn, consists of stone uprights ( stambha or thaba ), horizontal crossbars ( suchi ) and copings ( ushnisha ), most of which have inscriptions mentioning the names of donors. The three umbrellas on the summit symbolise the “Three Jewels” (tri-ratna) of Buddhism—the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.", <https://frontline.thehindu.com/arts-and-culture/heritage/buddhism-in-stone/article8932251.ece>、2024年1月15日閲覧

- ^ a b "Asoka and Sanchi Asoka also built the core of Stupa 1, known as Mahastupa or the Great Stupa, at Sanchi. The archaeologist M.K. Dhavalikar says this is indicated by the fact that the level of the stupa’s floor is the same as that of the Asokan pillar near by. Further, fragments of the chunar sandstone umbrella over the structure bear the characteristic mirror-like polish seen on Asokan pillars.", <https://frontline.thehindu.com/arts-and-culture/heritage/buddhism-in-stone/article8932251.ece>、2024年1月15日閲覧

- ^ 「阿育王傳」『大正新脩大蔵経』 史傳部 第50巻、大蔵出版。

- ^ "The construction of the mound, or Sthupa proper, is as follows : - In centre, a shaft, or , more probably, an inner mound, of brickwork ( the bricks measuring 16×10×3 inches), laid in mud, then loose stones and rubble ; and, outside, a casing of dressed stones, about eight inches thick, laid one over the other, in horizontal layers. The exterior was, once, coated with plaster, about four inches thick; portions of which I found still adhering to the building." GENERAL F.C. Maisey, SANCHI AND ITS REMAINS, Chapter III, KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO., 1882

- ^ "The complex was built over several hundred years. The core of the stupa was built of mud and brick by Asoka in the third century BCE."、<https://frontline.thehindu.com/arts-and-culture/heritage/buddhism-in-stone/article8932251.ece>、2024年1月15日閲覧

- ^ "Asoka’s mud-and-brick stupa got a stone encasing and was enlarged in the Shunga period. The ground balustrades, a berm, stairways, and the harmika were also built during this period, and so were Stupas 2 and 3."、<https://frontline.thehindu.com/arts-and-culture/heritage/buddhism-in-stone/article8932251.ece>、2024年1月15日閲覧

- ^ ″In the first century C.E., the Andhra-Satavahanas, who had extended their sway over eastern Malwa, constructed the elaborately carved gateways to Stupas 1 and 3.″, <https://frontline.thehindu.com/arts-and-culture/heritage/buddhism-in-stone/article8932251.ece>、2024年1月15日閲覧

- ^ a b c d World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India, Volume 1 p. 50 by Alī Jāvīd, Tabassum Javeed, Algora Publishing, New York [2]

- ^ The en:Butkara Stupa is an example of such a hemispherical stupa structure from the Maurya period, that was extensively documented through archaeological work

- ^ 大史では、ヴィディシャー近くのチャティヤギリと表現されている

- ^ Marshall, "A Guide to Sanchi" p. 8ff Public Domain text

- ^ Reconstitution with four lions and crowning wheel by Percy Brown: Diagram of Sanchi Great Stupa

- ^ a b Described in Marshall pp. 25-28 Ashoka pillar.

- ^ (英語) Encyclopaedia Indica: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh. Anmol Publications. (1996). p. 783. ISBN 978-81-7041-859-7. "It may be mentioned that the motif of lions carrying a wheel occurs at Sanchis which might be a representation of the Sarnath's Asokan pillar capital ."

- ^ a b Buddhist Architecture by Huu Phuoc Le p. 155

- ^ 塚本啓祥、「アショーカ王碑文」、第三文明社、1976

- ^ a b Marshall, "A Guide to Sanchi" p. 90ff Public Domain text

- ^ Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, p. 147

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2016) (アラビア語). The Idea of Ancient India: Essays on Religion, Politics, and Archaeology. SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9789351506454

- ^ Abram, David; (Firm), Rough Guides (2003). The Rough Guide to India. Rough Guides. ISBN 9781843530893

- ^ a b Marshall, John (1955). Guide to Sanchi

- ^ Chakrabarty, Dilip K. (2009). India: An Archaeological History: Palaeolithic Beginnings to Early Historic Foundations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199088140

- ^ "Who was responsible for the wanton destruction of the original brick stupa of en:Ashoka and when precisely the great work of reconstruction was carried out is not known, but it seems probable that the author of the former was Pushyamitra, the first of the Shunga kings (184-148 BC), who was notorious for his hostility to Buddhism, and that the restoration was affected by en:Agnimitra or his immediate successor." in John Marshall, A Guide to Sanchi, p. 38. Calcutta: Superintendent, Government Printing (1918).

- ^ Shaw, Julia (12 August 2016) (英語). Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, c. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD. Routledge. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-315-43263-2. ""It is inaccurate to refer to the post-Mauryan monuments at Sanchi as Sunga. Not only was Pusyamitra reputedly animical to Buddhism, but most of the donative inscriptions during this period attest to predominantly collective and nonroyal modes of sponsorship.""

- ^ a b c d Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, C. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD, Julia Shaw, Left Coast Press, 2013 p. 88ff

- ^ a b c d e Buddhist Architecture Huu Phuoc Le, Grafikol, 2010 p. 149

- ^ Marshall, John (1936). A guide to Sanchi. Patna: Eastern Book House. p. 36. ISBN 81-85204-32-2

- ^ a b c d Ornament in Indian Architecture Margaret Prosser Allen, University of Delaware Press, 1991 p. 18

- ^ a b c d e An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology, by en:Amalananda Ghosh, BRILL p. 295

- ^ a b c d e f Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, C. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD, Julia Shaw, Left Coast Press, 2013 p. 90

- ^ a b "The railing of Sanchi Stupa No.2, which represents the oldest extensive stupa decoration in existence, (and) dates from about the second century B.C.E." Constituting Communities: Theravada Buddhism and the Religious Cultures of South and Southeast Asia, John Clifford Holt, Jacob N. Kinnard, Jonathan S. Walters, SUNY Press, 2012 p. 197

- ^ a b Didactic Narration: Jataka Iconography in Dunhuang with a Catalogue of Jataka Representations in China, Alexander Peter Bell, LIT Verlag Münster, 2000 p. 15ff

- ^ Buddhist Architecture, Huu Phuoc Le, Grafikol, 2010 p. 149

- ^ Ancient Indian History and Civilization, Sailendra Nath Sen, New Age International, 1999 p. 170

- ^ An Indian Statuette From Pompeii, Mirella Levi D'Ancona, in Artibus Asiae, Vol. 13, No. 3 (1950) p. 171

- ^ Marshall p. 81

- ^ Marshall p. 82

- ^ a b Marhall, "A Guide to Sanchi" p. 95 Pillar 25. Public Domain text

- ^ a b Alcock, Susan E.; Alcock, John H. D'Arms Collegiate Professor of Classical Archaeology and Classics and Arthur F. Thurnau Professor Susan E.; D'Altroy, Terence N.; Morrison, Kathleen D.; Sinopoli, Carla M. (2001). Empires: Perspectives from Archaeology and History. Cambridge University Press. p. 169. ISBN 9780521770200

- ^ a b John Marshall, "A guide to Sanchi", p. 48

- ^ a b Indian History. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 251. ISBN 9781259063237

- ^ Jain, Kailash Chand (1972). Malwa Through The Ages. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.. p. 154. ISBN 9788120808249

- ^ a b A Guide to Sanchi, Marshall p. 65

- ^ Marshall p. 71

- ^ Marshall p. 55

- ^ [A Guide To Sanchi, Marshall, John, 1918 https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.35740 p. 37]

- ^ a b Lopez, Donald S Jr. (15 May 2023). "The Buddha's relics". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Strong, J.S. (2007). Relics of the Buddha. en:Princeton University Press. pp. 136–37. ISBN 978-0-691-11764-5

- ^ Marshall pp. 68-69

- ^ Asiatic Mythology by J. Hackin p. 83ff

- ^ Strong 2007, pp. 136–37.

- ^ Asoka and the Buddha-Relics, T.W. Rhys Davids, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1901, pp. 397-410 [3]

- ^ Asiatic Mythology by J. Hackin p. 84

- ^ a b Singh, Upinder (2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780674975279

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 333. ISBN 9788131711200

- ^ Thapar, Romila (2012). Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas. Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780199088683

- ^ 塚本啓祥、『アショーカ王碑文』、第三文明社、1976(2013に電子書籍化)

- ^ a b Ashoka in Ancient India Nayanjot Lahiri, Harvard University Press, 2015 p. 296

- ^ a b c d "Musicians generally described as "Greeks" from the eastern gateway at Sanchi" in Stoneman, Richard (2019). The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton University Press. pp. 441–444, Fig. 15.6. ISBN 9780691185385

- ^ "Sculptures showing Greeks or the Greek type of human figures are not lacking in ancient India. Apart from the proverbial Gandhara, Sanchi and Mathura have also yielded many sculptures that betray a close observation of the Greeks." in Graeco-Indica, India's cultural contacts, by en:Udai Prakash Arora, published by Ramanand Vidya Bhawan, 1991, p. 12

- ^ These "Greek-looking foreigners" are also described in Susan Huntington, "The art of ancient India", p. 100

- ^ Sanchi notice "Foreigners worshiping Stupa"

- ^ "The Greeks evidently introduced the himation and the chiton seen in the terracottas from Taxila and the short kilt worn by the soldier on the Sanchi relief." in Foreign influence on Indian culture: from c. 600 B.C. to 320 A.D., Manjari Ukil Originals, 2006, p. 162

- ^ a b "The scene shows musicians playing a variety of instruments, some of them quite extraordinary such as the Greek double flute and wind instruments with dragon head from West Asia" in The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia, Himanshu Prabha Ray, Cambridge University Press, 2003 p. 255

- ^ Purātattva, Number 8. Indian Archaeological Society. (1975). p. 188. "A reference to a Yona in the Sanchi inscriptions is also of immense value.(...) One of the inscriptions announces the gift of a Setapathia Yona, "Setapathiyasa Yonasa danam" i.e the gift of a Yona, inhabitant of Setapatha. The word Yona can't be here anything, but a Greek donor"

- ^ Epigraphia Indica Vol.2 p. 395 inscription 364

- ^ John Mashall, The Monuments of Sanchi p. 348 inscription No.475

- ^ a b c The Idea of Ancient India: Essays on Religion, Politics, and Archaeology, en:SAGE Publications India, Upinder Singh, 2016 p. 18

- ^ John Mashall, The Monuments of Sanchi p. 308 inscription No.89

- ^ John Mashall, The Monuments of Sanchi p. 345 inscription No.433

- ^ Faces of Power: Alexander's Image and Hellenistic Politics by Andrew Stewart p. 180

- ^ "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity", John Boardman, 1993, p. 112

- ^ "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity, John Boardman, 1993, p. 112 Note 91

- ^ a b Marshall p. 58 Third Panel

- ^ a b Marshall p. 64

- ^ A Guide to Sanchi, John Marshall

- ^ 訳注。十誦律(十誦律卷第四十八第八誦之一)と思われる。

- ^ 英語版の項目「en:Sanchi」の2024年1月20日時点のサブセクション 「Aniconism」に引用された次の英文の訳。""Since it is not permitted to make an image of the Buddha's body, I pray that the Buddha will grant that I can make an image of the attendant Bodhisattva. Is that acceptable?" The Buddha answered: "You may make an image of the Bodhisattava"". この原典はおそらく、十誦律の以下の部分と思われる。「爾時給孤獨居士信心清淨。往到佛所頭面作禮一面坐已。白佛言。世尊。如佛身像不應作。願佛聽我作菩薩侍像者善佛言。聽作。」、大正新脩大藏経 律部 第23巻 十誦律卷第四十八第八誦之一、(T1435、SAT大蔵経DB 2018)

- ^ Rhi, Ju-Hyung (1994). “From Bodhisattva to Buddha: The Beginning of Iconic Representation in Buddhist Art”. Artibus Asiae 54 (3/4): 220–221. doi:10.2307/3250056. JSTOR 3250056.

- ^ Indian Numismatic Studies by K. D. Bajpai p. 100、要検証

- ^ Ornament in Indian Architecture, Margaret Prosser Allen, University of Delaware Press, 1991 p. 18、要検証

- ^ a b Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press for the Royal Asiatic Society. (1851). pp. 108–109

- ^ Wright, Colin. “'Miscellaneous Series. Plate.12. Juma Masjid, Chanderi'. Maisey in a top-hat sketching in the foreground”. www.bl.uk

- ^ John Marshall, "An Historical and Artistic Description of Sanchi", from A Guide to Sanchi, Calcutta: Superintendent, Government Printing (1918). pp. 7-29 on line, Project South Asia.Archived 10 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Percy Brown, Indian Architecture, 1955

- 1 サーンチーとは

- 2 サーンチーの概要

- 3 概要

- 4 サーンチーの大仏塔(第一塔)

- 5 マウリヤ時代(紀元前3世紀)

- 6 シュンガ時代(紀元前2世紀頃)

- 7 サータヴァーハナ時代(紀元前1世紀 - 紀元1世紀頃)

- 8 その後の時代

- 9 ギャラリー

サーンチーと同じ種類の言葉

- サーンチーのページへのリンク