Rosetta@home

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2024/04/07 08:26 UTC 版)

| |

| |

| 作者 | Baker laboratory, University of Washington; Rosetta Commons |

|---|---|

| 初版 | 2005年10月6日 |

| 最新版 |

Rosetta: 4.20

/ 2020年5月1日 Rosetta Mini: 3.78 / 2017年10月3日 Rosetta for Android: 4.20 / 2020年5月1日 |

| 対応OS | Windows, macOS, Linux, Android |

| プラットフォーム | BOINC |

| 対応言語 | 英語 |

| サポート状況 | Active |

| 種別 | 分散コンピューティング |

| 公式サイト |

boinc |

概要

Rosetta@homeは、2022年3月14日時点で平均73,712.4 G(ギガ)FLOPS(フロップス)以上の処理能力を持つ約6万3,000台のアクティブなボランティアコンピュータの助けを借りて[1]、タンパク質-タンパク質ドッキング (英語版) を予測し、新しいタンパク質を設計することを目的としている。 Rosetta@Home のビデオゲームである Foldit は、クラウドソーシングのアプローチでこれらの目標を達成することを目指している。 プロジェクトの多くは、プロテオミクス手法の精度とロバスト性を向上させるための基礎研究に重点を置いているが、Rosetta@homeはマラリアやアルツハイマー病などの応用研究も行っている[2]。

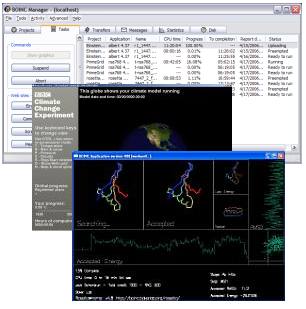

他の BOINC プロジェクトと同様に、Rosetta@home は、ボランティアのコンピュータからの未使用時の計算処理資源を使用して、個々の作業単位(ワークユニット) (英語版) の計算を実行する。完成した結果は中央のプロジェクトサーバーに送られ、そこで検証され、プロジェクトデータベースに統合される。このプロジェクトはクロスプラットフォームで、さまざまなハードウェア構成で動作する。ユーザは、個々のタンパク質構造予測の進捗状況を Rosetta@home スクリーンセーバーで確認することができる。

タンパク質の構造予測の問題は、Googleが所有するDeepMindが人工知能を使用して既に解決している。DeepMindは、タンパク質の構造を最も正確に予測するために、Rosettaの入力を他の多くのデータに取り入れた予測ツールAlphaFoldを開発した。AlphaFoldは、タンパク質構造予測技術精密評価(CASP)コンテストでRosettaを追い抜き、タンパク質の配列データを持つ約100万の生物種から2億以上のタンパク質の構造を予測するのに成功し、実質的にタンパク質宇宙を網羅した。すべての予測結果を含む構造データベースは、DeepMindと欧州バイオインフォマティクス研究所によって共同で構築された[3]。

疾患関連の研究に加えて、Rosetta@homeネットワークは、構造バイオインフォマティクスの新しい手法のテストフレームワークとしても機能する。そのような手法は、RosettaDock やヒトプロテオーム・フォールディング・プロジェクト (英語版) 、マイクロバイオーム免疫プロジェクトなどの Rosetta ベースの他のアプリケーションで使用され、Rosetta@home の大規模で多様なボランティアコンピュータで十分に開発され、安定していることが証明された後に使用される。Rosetta@home で開発された新しい手法の特に重要なテストは、タンパク質構造予測技術精密評価(CASP)とタンパク質間相互作用予測精密評価(CAPRI)実験であり、2年に1度の実験で、それぞれタンパク質構造予測とタンパク質-タンパク質ドッキング予測の最先端の状態を評価する。Rosetta@homeは常に主要なドッキング予測器の中にランク付けされており、利用可能な最高の三次構造予測器の一つである。

新型コロナウイルス感染症(COVID-19)の原因ウイルスSARS-CoV-2の解析プロジェクトに参加したいという新規ユーザの流入に伴い[4]、Rosetta@homeは2020年3月28日時点で最大1.7ペタフロップスまで計算能力を向上させた[5][6]。2020年9月9日、Rosetta@homeの研究者は、SARS-CoV-2に対する10種の強力な抗ウイルス剤候補を説明する論文を発表した。Rosetta@homeはこの研究に貢献し、これらの抗ウイルス剤候補は、第1相臨床試験 (2022年初頭に開始される可能性がある) に向かっている[7][8][9][10]。Rosetta@homeチームによると、Rosettaのボランティアはナノ粒子ワクチンの開発に貢献した[7]。このワクチンはライセンスされ、2021年6月に第I/II相臨床試験を開始したIcosavaxのIVX-411と[11]、SK Bioscienceが開発中で、韓国ですでに第III相臨床試験が承認されている(Skycovione) GBP510として知られている[12][13]。

また、Institute of Protein Design (IPD) で初めて作成され、2019年1月に論文発表された抗がん剤候補のNL-201は[14]、IPDからスピンオフしたNeoleukin Therapeuticsの支援を受けて、2021年5月に第1相ヒト臨床試験を開始した[15]。Rosetta@homeはNL-201の開発で役割を果たし、タンパク質設計の検証に役立つ「フォワードフォールディング」実験で貢献した[16]。

コンピューティング・プラットフォーム

Rosetta@home アプリケーションと BOINC 分散コンピューティングプラットフォームは、Windows、Linux、macOS の各 OS で利用可能である。 BOINC は、FreeBSD のような他のオペレーティングシステムでも動作する[17]。Rosetta@homeに参加するには、クロック速度500MHz以上の中央処理装置(CPU)、200メガバイトの空きディスク容量、512メガバイトの物理メモリ、インターネット接続が必要である[18]。2017年10月3日現在、Rosetta Miniアプリケーションの現在のバージョンは3.78である[19]。現在の推奨BOINCプログラムバージョンは7.6.22である[20]。ユーザーの BOINC クライアントとワシントン大学の Rosetta@home サーバー間の通信には標準ハイパーテキスト転送プロトコル (HTTP) (ポート80) が使用され、パスワード交換時には HTTPS (ポート443)が使用される。BOINC クライアントのリモートおよびローカル制御ではポート 31416 とポート 1043 を使用しているが、これらはファイアウォールの内側にある場合は特にブロック解除を要する可能性がある[21]。個々のタンパク質のデータを含むワークユニット (英語版) は、ワシントン大学のBaker研究室にあるサーバーからボランティアのコンピュータに配信され、割り当てられたタンパク質の構造予測を計算する。与えられたタンパク質の構造予測の重複を避けるために、各ワークユニットはランダムなシード番号 (英語版) で初期化される。これにより、各予測は、タンパク質のエネルギー地形に沿って下降するユニークな軌跡を得ることができる[22]。Rosetta@home からのタンパク質構造予測は、与えられたタンパク質のエネルギーランドスケープにおけるグローバルな最小値の近似値である。このグローバルな最小値は、タンパク質の最もエネルギー的に有利なコンフォメーション、すなわちネイティブな状態 (英語版) を表す。

Rosetta@home グラフィカル・ユーザー・インターフェース(GUI)の主な機能は、シミュレーションされたタンパク質の折り畳みプロセス中の現在のワークユニットの進行状況を表示するスクリーンセーバーである。スクリーンセーバーには次が表示される:[23]

- タンパク質の構造

- (左上) ターゲットとなるタンパク質が、最も低いエネルギーの構造を求めて様々な形状(コンフォーメーション)に変化している様子

- (中央上) 最近の構造

- (右上) 現在の最も低いエネルギーの構造

- (その下) すでに決定されている場合は真の構造

- グラフ

他のBOINCプロジェクトと同様に、Rosetta@homeは、ホストOSのアカウントにログインする前に、アイドル状態のコンピュータの電力を使って、ユーザのコンピュータのバックグラウンドで実行される。プログラムは、他のアプリケーションが必要とする CPU からリソースを解放し、通常のコンピュータの使用に影響を与えない。多くのプログラム設定は、ユーザーアカウントの環境設定を介して指定することができる。プログラムが使用できる CPU リソースの最大割合(持続的な容量で実行されているコンピュータの消費電力や発熱を制御するため)、プログラムを実行できる 1 日の時間帯、その他多くの設定がある[要出典]。

Rosetta@home ネットワーク上で動作するソフトウェアである Rosetta は、Fortran で書かれたオリジナルバージョンよりも開発が容易になるように C++ で書き直された。この新バージョンはオブジェクト指向で、2008年2月8日にリリースされた[24][25]。ロゼッタコードの開発はロゼッタコモンズによって行われている。このソフトウェアはアカデミックコミュニティに自由にライセンスされており、製薬会社には有償で提供されている[26]。

- ^ “Rosetta@home”. 2022年3月14日閲覧。

- ^ “What is Rosetta@home?”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Callaway E (July 2022). “The entire protein universe: AI predicts shape of nearly every known protein”. Nature 608: 15-16. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-02083-2.

- ^ “Help in the fight against COVID-19!”. Rosetta@home. 2020年4月13日閲覧。

- ^ Lensink MF, Méndez R, Wodak SJ (December 2007). “Docking and scoring protein complexes: CAPRI 3rd Edition”. Proteins 69 (4): 704–18. doi:10.1002/prot.21804. PMID 17918726.

- ^ “Rosetta@home Rallies a Legion of Computers Against the Coronavirus”. HPCWire (2020年3月24日). 2020年3月25日閲覧。

- ^ a b Rosetta@home (2021年6月25日). “The COVID-19 projects on our platform are headed into human clinical trials! Our amazing online volunteers have played a role in the development of a promising new vaccine as well as candidate antiviral treatments.” (英語). Twitter. 2021年6月26日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年6月26日閲覧。

- ^ Cao L, Goreshnik I, Coventry B, Case JB, Miller L, Kozodoy L, Chen RE, Carter L, Walls AC, Park YJ, Strauch EM, Stewart L, Diamond MS, Veesler D, Baker D (October 2020). “De novo design of picomolar SARS-CoV-2 miniprotein inhibitors”. Science 370 (6515): 426–431. Bibcode: 2020Sci...370..426C. doi:10.1126/science.abd9909. PMC 7857403. PMID 32907861.

- ^ “Coronavirus update from David Baker. Thank you all for your contributions!”. Rosetta@home. Rosetta@home (2020年9月21日). 2020年10月30日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年9月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “IPD Annual Report 2021”. Institute for Protein Design (2021年7月14日). 2021年8月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年8月18日閲覧。

- ^ “ANZCTR - Registration”. anzctr.org.au. 2021年10月30日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年7月9日閲覧。

- ^ “S. Korea approves Phase III trial of SK Bioscience's COVID-19 vaccine” (英語). Reuters (2021年8月10日). 2021年8月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年8月18日閲覧。

- ^ Institute of Protein Design (2021年8月10日). “Archived copy” (英語). Twitter. 2021年8月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年8月18日閲覧。

- ^ Silva DA, Yu S, Ulge UY, Spangler JB, Jude KM, Labão-Almeida C, Ali LR, Quijano-Rubio A, Ruterbusch M, Leung I, Biary T, Crowley SJ, Marcos E, Walkey CD, Weitzner BD, Pardo-Avila F, Castellanos J, Carter L, Stewart L, Riddell SR, Pepper M, Bernardes GJ, Dougan M, Garcia KC, Baker D (January 2019). “De novo design of potent and selective mimics of IL-2 and IL-15.”. Nature 565 (7738): 186–191. Bibcode: 2019Natur.565..186S. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0830-7. PMC 6521699. PMID 30626941.

- ^ “Neoleukin Therapeutics Announces Initiation of Phase 1 NL-201 Trial | Neoleukin Therapeutics, Inc.” (英語). investor.neoleukin.com. 2021年6月24日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年6月22日閲覧。

- ^ “Another publication in Nature describing the first de novo designed proteins with anti-cancer activity”. Rosetta@home (2020年1月14日). 2020年10月19日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Download BOINC client software”. BOINC. University of California (2008年). 2008年12月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Recommended System Requirements”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2008年). 2008年9月25日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: News archive”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2016年). 2016年7月20日閲覧。

- ^ “Download BOINC client software”. BOINC. University of California (2008年). 2008年12月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: FAQ (work in progress) (message 10910)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington (2006年). 2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ Kim DE (2005年). “Rosetta@home: Random Seed (message 3155)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Quick guide to Rosetta and its graphics”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2007年). 2008年9月24日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: News archive”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2016年). 2016年7月20日閲覧。

- ^ Kim DE (2008年). “Rosetta@home: Problems with minirosetta version 1.+ (Message 51199)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta Commons”. RosettaCommons.org (2008年). 2008年9月15日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Yearly Growth of Protein Structures”. RCSB Protein Data Bank (2008年). 2008年11月30日閲覧。

- ^ Baker D (2008年). “Rosetta@home: David Baker's Rosetta@home journal (message 55893)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Research Overview”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2007年). 2008年9月25日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ Kopp J, Bordoli L, Battey JN, Kiefer F, Schwede T (2007). “Assessment of CASP7 predictions for template-based modeling targets”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 38–56. doi:10.1002/prot.21753. PMID 17894352.

- ^ Read RJ, Chavali G (2007). “Assessment of CASP7 predictions in the high accuracy template-based modeling category”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 27–37. doi:10.1002/prot.21662. PMID 17894351.

- ^ Jauch R, Yeo HC, Kolatkar PR, Clarke ND (2007). “Assessment of CASP7 structure predictions for template free targets”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 57–67. doi:10.1002/prot.21771. PMID 17894330.

- ^ Das R, Qian B, Raman S, etal (2007). “Structure prediction for CASP7 targets using extensive all-atom refinement with Rosetta@home”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 118–28. doi:10.1002/prot.21636. PMID 17894356.

- ^ Wang C, Schueler-Furman O, Andre I, etal (December 2007). “RosettaDock in CAPRI rounds 6–12”. Proteins 69 (4): 758–63. doi:10.1002/prot.21684. PMID 17671979.

- ^ Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, etal (March 2008). “De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes”. Science 319 (5868): 1387–91. Bibcode: 2008Sci...319.1387J. doi:10.1126/science.1152692. PMC 3431203. PMID 18323453.

- ^ Hayden EC (February 13, 2008). “Protein prize up for grabs after retraction”. Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2008.569.

- ^ Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, etal (March 2008). “De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes”. Science 319 (5868): 1387–91. Bibcode: 2008Sci...319.1387J. doi:10.1126/science.1152692. PMC 3431203. PMID 18323453.

- ^ Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, etal (March 2008). “De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes”. Science 319 (5868): 1387–91. Bibcode: 2008Sci...319.1387J. doi:10.1126/science.1152692. PMC 3431203. PMID 18323453.

- ^ “Disease Related Research”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2008年). 2008年9月23日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月8日閲覧。

- ^ Baker D (2008年). “Rosetta@home: David Baker's Rosetta@home journal”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home Research Updates”. Boinc.bakerlab.org. 2014年4月18日閲覧。

- ^ “News archive”. Rosetta@home. 2019年5月10日閲覧。

- ^ Kuhlman B, Baker D (September 2000). “Native protein sequences are close to optimal for their structures”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97 (19): 10383–88. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...9710383K. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.19.10383. PMC 27033. PMID 10984534.

- ^ Thompson MJ, Sievers SA, Karanicolas J, Ivanova MI, Baker D, Eisenberg D (March 2006). “The 3D profile method for identifying fibril-forming segments of proteins”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (11): 4074–78. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..103.4074T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0511295103. PMC 1449648. PMID 16537487.

- ^ Bradley P. “Rosetta@home forum: Amyloid fibril structure prediction”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Baker D. “Rosetta@home forum: Publications on R@H's Alzheimer's work? (message 54681)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年10月8日閲覧。

- ^ Wang C, Schueler-Furman O, Baker D (May 2005). “Improved side-chain modeling for protein–protein docking”. Protein Science 14 (5): 1328–39. doi:10.1110/ps.041222905. PMC 2253276. PMID 15802647.

- ^ Gray JJ, Moughon S, Wang C, etal (August 2003). “Protein–protein docking with simultaneous optimization of rigid-body displacement and side-chain conformations”. Journal of Molecular Biology 331 (1): 281–99. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00670-3. PMID 12875852.

- ^ Schueler-Furman O, Wang C, Baker D (August 2005). “Progress in protein–protein docking: atomic resolution predictions in the CAPRI experiment using RosettaDock with an improved treatment of side-chain flexibility”. Proteins 60 (2): 187–94. doi:10.1002/prot.20556. PMID 15981249.

- ^ Lacy DB, Lin HC, Melnyk RA, etal (November 2005). “A model of anthrax toxin lethal factor bound to protective antigen”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (45): 16409–14. Bibcode: 2005PNAS..10216409L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0508259102. PMC 1283467. PMID 16251269.

- ^ Albrecht MT, Li H, Williamson ED, etal (November 2007). “Human monoclonal antibodies against anthrax lethal factor and protective antigen act independently to protect against Bacillus anthracis infection and enhance endogenous immunity to anthrax”. Infection and Immunity 75 (11): 5425–33. doi:10.1128/IAI.00261-07. PMC 2168292. PMID 17646360.

- ^ Sprague ER, Wang C, Baker D, Bjorkman PJ (June 2006). “Crystal structure of the HSV-1 Fc receptor bound to Fc reveals a mechanism for antibody bipolar bridging”. PLOS Biology 4 (6): e148. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040148. PMC 1450327. PMID 16646632.

- ^ Paulson, Tom (2006年7月19日). “Gates Foundation awards $287 million for HIV vaccine research”. Seattle Post-Intelligencer 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Liu Y, etal (2007年). “Development of IgG1 b12 scaffolds and HIV-1 env-based outer domain immunogens capable of eliciting and detecting IgG1 b12-like antibodies”. Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise. 2009年2月25日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年9月28日閲覧。

- ^ Baker D. “David Baker's Rosetta@home journal archives (message 40756)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Homing Endonuclease Genes: New Tools for Mosquito Population Engineering and Control”. Grand Challenges in Global Health. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Windbichler N, Papathanos PA, Catteruccia F, Ranson H, Burt A, Crisanti A (2007). “Homing endonuclease mediated gene targeting in Anopheles gambiae cells and embryos”. Nucleic Acids Research 35 (17): 5922–33. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm632. PMC 2034484. PMID 17726053.

- ^ “Disease Related Research”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2008年). 2008年9月23日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月8日閲覧。

- ^ Ashworth J, Havranek JJ, Duarte CM, etal (June 2006). “Computational redesign of endonuclease DNA binding and cleavage specificity”. Nature 441 (7093): 656–59. Bibcode: 2006Natur.441..656A. doi:10.1038/nature04818. PMC 2999987. PMID 16738662.

- ^ “Rosetta's role in fighting coronavirus – Institute for Protein Design” (英語). 2020年3月6日閲覧。

- ^ “Coronavirus Research Update”. Rosetta@home Official Twitter. Rosetta@Home (2020年6月26日). 2020年6月27日閲覧。

- ^ Cao, Longxing (2020-09-09). “De novo design of picomolar SARS-CoV-2 miniprotein inhibitors”. Science: eabd9909. doi:10.1126/science.abd9909. PMID 32907861.

- ^ Case JB, Chen RE, Cao L, Ying B, Winkler ES, Johnson M, Goreshnik I, Pham MN, Shrihari S, Kafai NM, Bailey AL, Xie X, Shi PY, Ravichandran R, Carter L, Stewart L, Baker D, Diamond MS (July 2021). “Ultrapotent miniproteins targeting the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain protect against infection and disease” (English). Cell Host & Microbe 29 (7): 1151–1161.e5. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2021.06.008. PMC 8221914. PMID 34192518.

- ^ Hunt AC, Case JB, Park YJ, Cao L, Wu K, Walls AC, Liu Z, Bowen JE, Yeh HW, Saini S, Helms L, Zhao YT, Hsiang TY, Starr TN, Goreshnik I, Kozodoy L, Carter L, Ravichandran R, Green LB, Matochko WL, Thomson CA, Vögeli B, Krüger-Gericke A, VanBlargan LA, Chen RE, Ying B, Bailey AL, Kafai NM, Boyken S, Ljubetič A, Edman N, Ueda G, Chow C, Addetia A, Panpradist N, Gale M, Freedman BS, Lutz BR, Bloom JD, Ruohola-Baker H, Whelan SP, Stewart L, Diamond MS, Veesler D, Jewett MC, Baker D (July 2021). “Multivalent designed proteins protect against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern”. bioRxiv: 2021.07.07.451375. doi:10.1101/2021.07.07.451375. PMC 8282097. PMID 34268509.

- ^ “Big news out of @UWproteindesign: a new candidate treatment for #COVID19! More lab testing still needed. Thanks to all the volunteers who helped crunch data for this project!!”. Rosetta@home Twitter. Rosetta@home Twitter (2020年9月9日). 2020年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ “De novo minibinders target SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein”. Baker Lab. Baker Lab (2020年9月9日). 2020年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ Silva DA, Yu S, Ulge UY, Spangler JB, Jude KM, Labão-Almeida C, Ali LR, Quijano-Rubio A, Ruterbusch M, Leung I, Biary T, Crowley SJ, Marcos E, Walkey CD, Weitzner BD, Pardo-Avila F, Castellanos J, Carter L, Stewart L, Riddell SR, Pepper M, Bernardes GJ, Dougan M, Garcia KC, Baker D (January 2019). “De novo design of potent and selective mimics of IL-2 and IL-15.”. Nature 565 (7738): 186–191. Bibcode: 2019Natur.565..186S. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0830-7. PMC 6521699. PMID 30626941.

- ^ “Another publication in Nature describing the first de novo designed proteins with anti-cancer activity”. Rosetta@home (2020年1月14日). 2020年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ Hutson, Matthew (2020年9月18日). “Scientists Advance on One of Technology's Holy Grails”. The New Yorker 2020年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Neoleukin Therapeutics Announces Submission of Investigational New Drug Application for NL-201 De Novo Protein Immunotherapy Candidate for Cancer”. Neoleukin Therapeutics (2020年12月10日). 2020年12月10日閲覧。

- ^ Simons KT, Bonneau R, Ruczinski I, Baker D (1999). “Ab initio protein structure prediction of CASP III targets using Rosetta”. Proteins Suppl 3: 171–76. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(1999)37:3+<171::AID-PROT21>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 10526365.

- ^ “Interview with David Baker”. Team Picard Distributed Computing (2006年). 2009年2月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年12月23日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: News archive”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2016年). 2016年7月20日閲覧。

- ^ Nauli S, Kuhlman B, Baker D (July 2001). “Computer-based redesign of a protein folding pathway”. Nature Structural Biology 8 (7): 602–05. doi:10.1038/89638. PMID 11427890.

- ^ Kuhlman B, Dantas G, Ireton GC, Varani G, Stoddard BL, Baker D (November 2003). “Design of a novel globular protein fold with atomic-level accuracy”. Science 302 (5649): 1364–68. Bibcode: 2003Sci...302.1364K. doi:10.1126/science.1089427. PMID 14631033.

- ^ Jones DT (November 2003). “Structural biology. Learning to speak the language of proteins”. Science 302 (5649): 1347–48. doi:10.1126/science.1092492. PMID 14631028.

- ^ von Grotthuss M, Wyrwicz LS, Pas J, Rychlewski L (June 2004). “Predicting protein structures accurately”. Science 304 (5677): 1597–99; author reply 1597–99. doi:10.1126/science.304.5677.1597b. PMID 15192202.

- ^ “Articles citing: Kuhlman et al. (2003) 'Design of a novel globular protein fold with atomic-level accuracy'”. ISI Web of Science. 2008年7月10日閲覧。

- ^ “October 2005 molecule of the month: Designer proteins”. RCSB Protein Data Bank. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Research Overview”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2007年). 2008年9月25日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Kuhlman laboratory homepage”. Kuhlman Laboratory. University of North Carolina. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “RosettaDesign web server”. Kuhlman Laboratory. University of North Carolina. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Gray JJ, Moughon SE, Kortemme T, etal (July 2003). “Protein–protein docking predictions for the CAPRI experiment”. Proteins 52 (1): 118–22. doi:10.1002/prot.10384. PMID 12784377.

- ^ Gray JJ, Moughon SE, Kortemme T, etal (July 2003). “Protein–protein docking predictions for the CAPRI experiment”. Proteins 52 (1): 118–22. doi:10.1002/prot.10384. PMID 12784377.

- ^ Schueler-Furman O, Wang C, Baker D (August 2005). “Progress in protein–protein docking: atomic resolution predictions in the CAPRI experiment using RosettaDock with an improved treatment of side-chain flexibility”. Proteins 60 (2): 187–94. doi:10.1002/prot.20556. PMID 15981249.

- ^ Daily MD, Masica D, Sivasubramanian A, Somarouthu S, Gray JJ (2005). “CAPRI rounds 3–5 reveal promising successes and future challenges for RosettaDock”. Proteins 60 (2): 181–86. doi:10.1002/prot.20555. PMID 15981262.

- ^ Méndez R, Leplae R, Lensink MF, Wodak SJ (2005). “Assessment of CAPRI predictions in rounds 3–5 shows progress in docking procedures”. Proteins 60 (2): 150–69. doi:10.1002/prot.20551. PMID 15981261.

- ^ “RosettaDock server”. Rosetta Commons. 2020年3月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Protein–protein docking at Rosetta@home”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Lensink MF, Méndez R, Wodak SJ (December 2007). “Docking and scoring protein complexes: CAPRI 3rd Edition”. Proteins 69 (4): 704–18. doi:10.1002/prot.21804. PMID 17918726.

- ^ Wang C, Schueler-Furman O, Andre I, etal (December 2007). “RosettaDock in CAPRI rounds 6–12”. Proteins 69 (4): 758–63. doi:10.1002/prot.21684. PMID 17671979.

- ^ “Robetta web server”. Baker laboratory. University of Washington. 2019年5月7日閲覧。

- ^ Aloy P, Stark A, Hadley C, Russell RB (2003). “Predictions without templates: new folds, secondary structure, and contacts in CASP5”. Proteins 53 Suppl 6: 436–56. doi:10.1002/prot.10546. PMID 14579333.

- ^ Jauch R, Yeo HC, Kolatkar PR, Clarke ND (2007). “Assessment of CASP7 structure predictions for template free targets”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 57–67. doi:10.1002/prot.21771. PMID 17894330.

- ^ Tress M, Ezkurdia I, Graña O, López G, Valencia A (2005). “Assessment of predictions submitted for the CASP6 comparative modeling category”. Proteins 61 Suppl 7: 27–45. doi:10.1002/prot.20720. PMID 16187345.

- ^ Battey JN, Kopp J, Bordoli L, Read RJ, Clarke ND, Schwede T (2007). “Automated server predictions in CASP7”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 68–82. doi:10.1002/prot.21761. PMID 17894354.

- ^ Chivian D, Kim DE, Malmström L, Schonbrun J, Rohl CA, Baker D (2005). “Prediction of CASP6 structures using automated Robetta protocols”. Proteins 61 Suppl 7: 157–66. doi:10.1002/prot.20733. PMID 16187358.

- ^ Baker D. “David Baker's Rosetta@home journal, message 52902”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Das R, Qian B, Raman S, etal (2007). “Structure prediction for CASP7 targets using extensive all-atom refinement with Rosetta@home”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 118–28. doi:10.1002/prot.21636. PMID 17894356.

- ^ Ovchinnikov, S; Kim, DE; Wang, RY; Liu, Y; DiMaio, F; Baker, D (September 2016). “Improved de novo structure prediction in CASP11 by incorporating coevolution information into Rosetta.”. Proteins 84 Suppl 1: 67–75. doi:10.1002/prot.24974. PMC 5490371. PMID 26677056.

- ^ Baker D. “David Baker's Rosetta@home journal (message 52963)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月16日閲覧。

- ^ “Foldit forums: How many users does Foldit have? Etc. (message 2)”. University of Washington. 2008年9月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Foldit: Frequently Asked Questions”. fold.it. University of Washington. 2008年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Project list – BOINC”. University of California. 2008年9月8日閲覧。

- ^ Pande Group (2010年). “High Performance FAQ” (FAQ). Stanford University. 2012年9月21日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2011年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ 7im (2010年4月2日). “Re: Answers to: Reasons for not using F@H”. 2011年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ Vijay Pande (2011年8月5日). “Results page updated – new key result published in our work in Alzheimer's Disease”. 2011年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ Pande Group. “Folding@home Diseases Studied FAQ” (FAQ). Stanford University. 2007年10月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2011年9月12日閲覧。

- ^ Vijay Pande (2007年9月26日). “How FAH works: Molecular dynamics”. 2011年9月10日閲覧。

- ^ tjlane (2011年6月9日). “Re: Course grained Protein folding in under 10 minutes”. 2011年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ tjlane (2011年6月9日). “Re: Course grained Protein folding in under 10 minutes”. 2011年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ jmn (2011年7月29日). “Rosetta@home and Folding@home: additional projects”. 2011年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ Pande Group. “Client Statistics by OS”. Stanford University. 2011年10月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Credit overview”. boincstats.com. 2020年3月28日閲覧。

- ^ Malmström L, Riffle M, Strauss CE, etal (April 2007). “Superfamily assignments for the yeast proteome through integration of structure prediction with the gene ontology”. PLOS Biology 5 (4): e76. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050076. PMC 1828141. PMID 17373854.

- ^ Bonneau R (2006年). “World Community Grid Message Board Posts: HPF -> HPF2 transition”. Bonneau Lab, New York University. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “List of Richard Bonneau's publications”. Bonneau Lab, New York University. 2008年7月7日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Bonneau R. “World Community Grid Message Board Posts”. Bonneau Lab, New York University. 2008年7月4日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “RALPH@home website”. RALPH@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Predictor@home: Developing new application areas for P@H”. The Brooks Research Group. 2008年9月7日閲覧。[リンク切れ]

- ^ Carrillo-Tripp M (2007年). “dTASSER”. The Scripps Research Institute. 2007年7月6日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Credit overview”. boincstats.com. 2020年3月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home”. 2020年3月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: The new credit system explained”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington (2006年). 2008年10月8日閲覧。

- ^ “BOINCstats: Project Credit Comparison”. boincstats.com (2008年). 2008年9月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月8日閲覧。

- ^ “Credit divided over projects”. boincstats.com. 2015年2月19日閲覧。

- ^ Das R, Qian B, Raman S, etal (2007). “Structure prediction for CASP7 targets using extensive all-atom refinement with Rosetta@home”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 118–28. doi:10.1002/prot.21636. PMID 17894356.

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Predictor of the day archive”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2008年). 2008年9月24日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月8日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Protein Folding, Design, and Docking”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2008年). 2008年10月8日閲覧。

- Rosetta@homeのページへのリンク