Rosetta@home

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2024/04/07 08:26 UTC 版)

開発の歴史と分科

Rosettaは、1998年にBaker研究室によって第一原理計算による構造予測[71]のためのアプローチとして導入されのが始まりで、それ以来、いくつかの開発ストリームと独自のサービスへと発展してきた。 Rosettaプラットフォームの名前は、タンパク質のアミノ酸配列の構造的な「意味」を解読しようとする「ロゼッタ・ストーン」に由来している[72]。Rosettaの登場から7年以上が経過し、2005年10月6日にRosetta@homeプロジェクトがリリースされた(つまり、ベータ版ではなくなったと発表された)[73]。Rosettaの初期開発に携わった大学院生やその他の研究者の多くは、その後、他の大学や研究機関に移っており、その後、Rosettaプロジェクトのさまざまな部分を強化してきた。

RosettaDesign

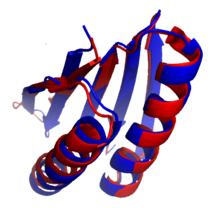

RosettaDesign(ロゼッタデザイン)は、Rosettaをベースにしたタンパク質設計のための計算機的アプローチで、2000年にはプロテインG[74]の折り畳み経路の再設計の研究から始まった。 2002年にはRosettaDesignを用いて、これまで自然界で記録されたことのない全体的な折り畳み (英語版) を持つ93アミノ酸長のα/βタンパク質 Top7を設計した。 この新しい構造は、Rosettaによって、X線結晶構造解析によって決定された構造のRMSDが1.2Å以内であることが予測され、これは非常に正確な構造予測であることを示している[75]。RosettaとRosettaDesignは、このような長さの新しいタンパク質の構造を設計し、正確に予測した最初の研究者として広く知られるようになったが、この二重のアプローチを説明した2002年の論文は、ジャーナル「Science」に2つのポジティブレターを掲載し[76][77]、他の240以上の科学論文で引用された[78]。この研究の成果物であるTop7は、2006年10月にRCSB PDBの「Molecule of the Month」として取り上げられ[79]、その予測結晶構造とX線結晶構造のそれぞれのコア(残基60〜79)を重ね合わせたものが、Rosetta@homeのロゴとして掲載されている[80]。

Brian Kuhlman氏は、元David Baker研究室で博士号を取得し、現在はノースカロライナ大学チャペルヒル校の准教授として[81]、RosettaDesignをオンラインサービスとして提供している[82]。

RosettaDock

RosettaDock (ロゼッタドック)は、2002 年の最初の CAPRI 実験の際に、Baker 研究室の蛋白質-蛋白質ドッキング予測のためのアルゴリズムとして Rosettaソフトウェアに追加された[83]。この実験では、RosettaDock は、連鎖球菌の化膿性エキソトキシンA と T細胞受容体β鎖とのドッキングを高精度で予測し、ブタの α-アミラーゼとラクダ科(Camelid, カメロイド)抗体との複合体を中精度で予測した。RosettaDock 法は、可能性のある7つの予測法のうち2つの精度の高い予測しかできなかったが、これは第1回CAPRI評価では19種類の予測法のうち7位にランク付けされるのに十分であった[84]。

ワシントン大学在学中に RosettaDock の基礎を築いた Jeffrey Gray が、ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学に移ってからも、RosettaDock の開発は、その後のCAPRIラウンドに向けて2つの分岐点に分かれた。 Baker 研究室のメンバーは、Grayの不在の間にRosettaDockをさらに開発した。 2つのバージョンは、側鎖のモデル化、デコイ (英語版) の選択、その他の分野で若干の違いがあった[85][86]。これらの違いにもかかわらず、BakerとGrayの両手法は、第2回CAPRI評価で30の予測グループの中でそれぞれ5位と7位にランクインし、良好な結果を残した[87]。Jeffrey Gray氏のRosettaDockサーバーは、非商用利用のための無料ドッキング予測サービスとして提供されている[88]。

2006年10月、RosettaDockはRosetta@homeに統合された。 この方法では、タンパク質のバックボーン (英語版) のみを使用した高速で粗いドッキングモデルのフェーズを使用した。 この段階では、相互作用する2つのタンパク質の相対的な配向、およびタンパク質-タンパク質界面での側鎖相互作用を同時に最適化して、最も低いエネルギーのコンフォメーションを見つけることができる[89]。Rosetta@homeネットワークによる計算能力の大幅な向上と、バックボーンの柔軟性とループモデリング (英語版) のための修正されたフォールドツリー表現との組み合わせにより、RosettaDockは第3回CAPRI評価で63の予測グループのうち6位になった[90][91]。

Robetta

Robetta (ロベッタ) (Rosetta Beta) サーバーは、Baker研究室が提供する非営利のab initioおよび比較モデリングのためのタンパク質構造予測の自動化サービスである[92]。Robettaは、2002年のCASP5以来、年2回のCASP実験に自動予測サーバーとして参加しており、自動化サーバー予測カテゴリでは最高の成績を収めている[93]。Robettaはそれ以降、CASP6とCASP7に参加し、自動化サーバと人間の予測グループの両方で平均以上の成績を収めている[94][95][96]。 また、CAMEO3D (英語版) の連続評価にも参加している。

CASP6のタンパク質構造をモデル化する際、Robettaはまず、BLAST、PSI-BLAST、3D-Jury (英語版) を用いて構造的相同性を検索し、その配列をPfamデータベースの構造ファミリと照合することで、ターゲット配列を個々のドメイン、またはタンパク質の独立したフォールディングユニットに解析する。 次に、構造的相同性を持つドメインは、「テンプレートベースモデル」(すなわち、ホモロジーモデリング)プロトコルに従う。ここでは、Baker研究室内のアラインメントプログラム「K*sync」が相同配列のグループを生成し、これらのそれぞれがロゼッタde novo法によってモデル化され、デコイ(可能性のある構造)が生成される。 最終的な構造予測は、低分解能ロゼッタエネルギー関数によって決定された最も低いエネルギーのモデルを取ることによって選択される。 検出された構造的相同性を持たないドメインについては、生成されたデコイのセットから最も低いエネルギーモデルを最終的な予測値として選択するde novoプロトコルに従う。 これらのドメイン予測を連結して、タンパク質内のドメイン間、三次レベルの相互作用を調査する。 最後に、モンテカルロ構造探索プロトコルを用いて側鎖の寄与をモデル化する[97]。

CASP8では、Rosettaの高分解能全原子精密化法[98]を使用するようにRobettaが拡張されたが、これがないためにCASP7のRosetta@homeネットワークよりも精度が低いと言われていた[99]。CASP11では、GREMLINと呼ばれる関連タンパク質の残基の共進化によるタンパク質コンタクトマップを予測する方法が追加され、より多くのde novoフォールドの成功を可能にした[100]。

Foldit

2008年5月9日、Rosetta@homeのユーザーが分散コンピューティングプログラムの対話型バージョンを提案したことを受けて、Baker研究室は、Rosettaプラットフォームをベースにしたオンラインのタンパク質構造予測ゲームFolditを公開した[101]。2008年9月25日の時点で、Folditの登録ユーザー数は59,000人を超えている[102]。このゲームでは、ユーザーは、ターゲットタンパク質のバックボーンやアミノ酸側鎖を操作して、よりエネルギー的に有利な構造にするための一連の操作(例えば、振る、くねくねする、再構築する)を行うことができる。 ユーザーは、ソロリストとして、またはエボルバーとして集団で解決策に取り組むことができ、構造予測を改善すると、どちらのカテゴリーでもポイントを獲得することができる[103]。

- ^ “Rosetta@home”. 2022年3月14日閲覧。

- ^ “What is Rosetta@home?”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Callaway E (July 2022). “The entire protein universe: AI predicts shape of nearly every known protein”. Nature 608: 15-16. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-02083-2.

- ^ “Help in the fight against COVID-19!”. Rosetta@home. 2020年4月13日閲覧。

- ^ Lensink MF, Méndez R, Wodak SJ (December 2007). “Docking and scoring protein complexes: CAPRI 3rd Edition”. Proteins 69 (4): 704–18. doi:10.1002/prot.21804. PMID 17918726.

- ^ “Rosetta@home Rallies a Legion of Computers Against the Coronavirus”. HPCWire (2020年3月24日). 2020年3月25日閲覧。

- ^ a b Rosetta@home (2021年6月25日). “The COVID-19 projects on our platform are headed into human clinical trials! Our amazing online volunteers have played a role in the development of a promising new vaccine as well as candidate antiviral treatments.” (英語). Twitter. 2021年6月26日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年6月26日閲覧。

- ^ Cao L, Goreshnik I, Coventry B, Case JB, Miller L, Kozodoy L, Chen RE, Carter L, Walls AC, Park YJ, Strauch EM, Stewart L, Diamond MS, Veesler D, Baker D (October 2020). “De novo design of picomolar SARS-CoV-2 miniprotein inhibitors”. Science 370 (6515): 426–431. Bibcode: 2020Sci...370..426C. doi:10.1126/science.abd9909. PMC 7857403. PMID 32907861.

- ^ “Coronavirus update from David Baker. Thank you all for your contributions!”. Rosetta@home. Rosetta@home (2020年9月21日). 2020年10月30日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年9月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “IPD Annual Report 2021”. Institute for Protein Design (2021年7月14日). 2021年8月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年8月18日閲覧。

- ^ “ANZCTR - Registration”. anzctr.org.au. 2021年10月30日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年7月9日閲覧。

- ^ “S. Korea approves Phase III trial of SK Bioscience's COVID-19 vaccine” (英語). Reuters (2021年8月10日). 2021年8月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年8月18日閲覧。

- ^ Institute of Protein Design (2021年8月10日). “Archived copy” (英語). Twitter. 2021年8月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年8月18日閲覧。

- ^ Silva DA, Yu S, Ulge UY, Spangler JB, Jude KM, Labão-Almeida C, Ali LR, Quijano-Rubio A, Ruterbusch M, Leung I, Biary T, Crowley SJ, Marcos E, Walkey CD, Weitzner BD, Pardo-Avila F, Castellanos J, Carter L, Stewart L, Riddell SR, Pepper M, Bernardes GJ, Dougan M, Garcia KC, Baker D (January 2019). “De novo design of potent and selective mimics of IL-2 and IL-15.”. Nature 565 (7738): 186–191. Bibcode: 2019Natur.565..186S. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0830-7. PMC 6521699. PMID 30626941.

- ^ “Neoleukin Therapeutics Announces Initiation of Phase 1 NL-201 Trial | Neoleukin Therapeutics, Inc.” (英語). investor.neoleukin.com. 2021年6月24日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年6月22日閲覧。

- ^ “Another publication in Nature describing the first de novo designed proteins with anti-cancer activity”. Rosetta@home (2020年1月14日). 2020年10月19日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Download BOINC client software”. BOINC. University of California (2008年). 2008年12月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Recommended System Requirements”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2008年). 2008年9月25日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: News archive”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2016年). 2016年7月20日閲覧。

- ^ “Download BOINC client software”. BOINC. University of California (2008年). 2008年12月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: FAQ (work in progress) (message 10910)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington (2006年). 2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ Kim DE (2005年). “Rosetta@home: Random Seed (message 3155)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Quick guide to Rosetta and its graphics”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2007年). 2008年9月24日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: News archive”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2016年). 2016年7月20日閲覧。

- ^ Kim DE (2008年). “Rosetta@home: Problems with minirosetta version 1.+ (Message 51199)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta Commons”. RosettaCommons.org (2008年). 2008年9月15日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Yearly Growth of Protein Structures”. RCSB Protein Data Bank (2008年). 2008年11月30日閲覧。

- ^ Baker D (2008年). “Rosetta@home: David Baker's Rosetta@home journal (message 55893)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Research Overview”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2007年). 2008年9月25日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ Kopp J, Bordoli L, Battey JN, Kiefer F, Schwede T (2007). “Assessment of CASP7 predictions for template-based modeling targets”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 38–56. doi:10.1002/prot.21753. PMID 17894352.

- ^ Read RJ, Chavali G (2007). “Assessment of CASP7 predictions in the high accuracy template-based modeling category”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 27–37. doi:10.1002/prot.21662. PMID 17894351.

- ^ Jauch R, Yeo HC, Kolatkar PR, Clarke ND (2007). “Assessment of CASP7 structure predictions for template free targets”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 57–67. doi:10.1002/prot.21771. PMID 17894330.

- ^ Das R, Qian B, Raman S, etal (2007). “Structure prediction for CASP7 targets using extensive all-atom refinement with Rosetta@home”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 118–28. doi:10.1002/prot.21636. PMID 17894356.

- ^ Wang C, Schueler-Furman O, Andre I, etal (December 2007). “RosettaDock in CAPRI rounds 6–12”. Proteins 69 (4): 758–63. doi:10.1002/prot.21684. PMID 17671979.

- ^ Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, etal (March 2008). “De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes”. Science 319 (5868): 1387–91. Bibcode: 2008Sci...319.1387J. doi:10.1126/science.1152692. PMC 3431203. PMID 18323453.

- ^ Hayden EC (February 13, 2008). “Protein prize up for grabs after retraction”. Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2008.569.

- ^ Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, etal (March 2008). “De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes”. Science 319 (5868): 1387–91. Bibcode: 2008Sci...319.1387J. doi:10.1126/science.1152692. PMC 3431203. PMID 18323453.

- ^ Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, etal (March 2008). “De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes”. Science 319 (5868): 1387–91. Bibcode: 2008Sci...319.1387J. doi:10.1126/science.1152692. PMC 3431203. PMID 18323453.

- ^ “Disease Related Research”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2008年). 2008年9月23日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月8日閲覧。

- ^ Baker D (2008年). “Rosetta@home: David Baker's Rosetta@home journal”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home Research Updates”. Boinc.bakerlab.org. 2014年4月18日閲覧。

- ^ “News archive”. Rosetta@home. 2019年5月10日閲覧。

- ^ Kuhlman B, Baker D (September 2000). “Native protein sequences are close to optimal for their structures”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97 (19): 10383–88. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...9710383K. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.19.10383. PMC 27033. PMID 10984534.

- ^ Thompson MJ, Sievers SA, Karanicolas J, Ivanova MI, Baker D, Eisenberg D (March 2006). “The 3D profile method for identifying fibril-forming segments of proteins”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (11): 4074–78. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..103.4074T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0511295103. PMC 1449648. PMID 16537487.

- ^ Bradley P. “Rosetta@home forum: Amyloid fibril structure prediction”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Baker D. “Rosetta@home forum: Publications on R@H's Alzheimer's work? (message 54681)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年10月8日閲覧。

- ^ Wang C, Schueler-Furman O, Baker D (May 2005). “Improved side-chain modeling for protein–protein docking”. Protein Science 14 (5): 1328–39. doi:10.1110/ps.041222905. PMC 2253276. PMID 15802647.

- ^ Gray JJ, Moughon S, Wang C, etal (August 2003). “Protein–protein docking with simultaneous optimization of rigid-body displacement and side-chain conformations”. Journal of Molecular Biology 331 (1): 281–99. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00670-3. PMID 12875852.

- ^ Schueler-Furman O, Wang C, Baker D (August 2005). “Progress in protein–protein docking: atomic resolution predictions in the CAPRI experiment using RosettaDock with an improved treatment of side-chain flexibility”. Proteins 60 (2): 187–94. doi:10.1002/prot.20556. PMID 15981249.

- ^ Lacy DB, Lin HC, Melnyk RA, etal (November 2005). “A model of anthrax toxin lethal factor bound to protective antigen”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (45): 16409–14. Bibcode: 2005PNAS..10216409L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0508259102. PMC 1283467. PMID 16251269.

- ^ Albrecht MT, Li H, Williamson ED, etal (November 2007). “Human monoclonal antibodies against anthrax lethal factor and protective antigen act independently to protect against Bacillus anthracis infection and enhance endogenous immunity to anthrax”. Infection and Immunity 75 (11): 5425–33. doi:10.1128/IAI.00261-07. PMC 2168292. PMID 17646360.

- ^ Sprague ER, Wang C, Baker D, Bjorkman PJ (June 2006). “Crystal structure of the HSV-1 Fc receptor bound to Fc reveals a mechanism for antibody bipolar bridging”. PLOS Biology 4 (6): e148. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040148. PMC 1450327. PMID 16646632.

- ^ Paulson, Tom (2006年7月19日). “Gates Foundation awards $287 million for HIV vaccine research”. Seattle Post-Intelligencer 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Liu Y, etal (2007年). “Development of IgG1 b12 scaffolds and HIV-1 env-based outer domain immunogens capable of eliciting and detecting IgG1 b12-like antibodies”. Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise. 2009年2月25日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年9月28日閲覧。

- ^ Baker D. “David Baker's Rosetta@home journal archives (message 40756)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Homing Endonuclease Genes: New Tools for Mosquito Population Engineering and Control”. Grand Challenges in Global Health. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Windbichler N, Papathanos PA, Catteruccia F, Ranson H, Burt A, Crisanti A (2007). “Homing endonuclease mediated gene targeting in Anopheles gambiae cells and embryos”. Nucleic Acids Research 35 (17): 5922–33. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm632. PMC 2034484. PMID 17726053.

- ^ “Disease Related Research”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2008年). 2008年9月23日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月8日閲覧。

- ^ Ashworth J, Havranek JJ, Duarte CM, etal (June 2006). “Computational redesign of endonuclease DNA binding and cleavage specificity”. Nature 441 (7093): 656–59. Bibcode: 2006Natur.441..656A. doi:10.1038/nature04818. PMC 2999987. PMID 16738662.

- ^ “Rosetta's role in fighting coronavirus – Institute for Protein Design” (英語). 2020年3月6日閲覧。

- ^ “Coronavirus Research Update”. Rosetta@home Official Twitter. Rosetta@Home (2020年6月26日). 2020年6月27日閲覧。

- ^ Cao, Longxing (2020-09-09). “De novo design of picomolar SARS-CoV-2 miniprotein inhibitors”. Science: eabd9909. doi:10.1126/science.abd9909. PMID 32907861.

- ^ Case JB, Chen RE, Cao L, Ying B, Winkler ES, Johnson M, Goreshnik I, Pham MN, Shrihari S, Kafai NM, Bailey AL, Xie X, Shi PY, Ravichandran R, Carter L, Stewart L, Baker D, Diamond MS (July 2021). “Ultrapotent miniproteins targeting the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain protect against infection and disease” (English). Cell Host & Microbe 29 (7): 1151–1161.e5. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2021.06.008. PMC 8221914. PMID 34192518.

- ^ Hunt AC, Case JB, Park YJ, Cao L, Wu K, Walls AC, Liu Z, Bowen JE, Yeh HW, Saini S, Helms L, Zhao YT, Hsiang TY, Starr TN, Goreshnik I, Kozodoy L, Carter L, Ravichandran R, Green LB, Matochko WL, Thomson CA, Vögeli B, Krüger-Gericke A, VanBlargan LA, Chen RE, Ying B, Bailey AL, Kafai NM, Boyken S, Ljubetič A, Edman N, Ueda G, Chow C, Addetia A, Panpradist N, Gale M, Freedman BS, Lutz BR, Bloom JD, Ruohola-Baker H, Whelan SP, Stewart L, Diamond MS, Veesler D, Jewett MC, Baker D (July 2021). “Multivalent designed proteins protect against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern”. bioRxiv: 2021.07.07.451375. doi:10.1101/2021.07.07.451375. PMC 8282097. PMID 34268509.

- ^ “Big news out of @UWproteindesign: a new candidate treatment for #COVID19! More lab testing still needed. Thanks to all the volunteers who helped crunch data for this project!!”. Rosetta@home Twitter. Rosetta@home Twitter (2020年9月9日). 2020年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ “De novo minibinders target SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein”. Baker Lab. Baker Lab (2020年9月9日). 2020年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ Silva DA, Yu S, Ulge UY, Spangler JB, Jude KM, Labão-Almeida C, Ali LR, Quijano-Rubio A, Ruterbusch M, Leung I, Biary T, Crowley SJ, Marcos E, Walkey CD, Weitzner BD, Pardo-Avila F, Castellanos J, Carter L, Stewart L, Riddell SR, Pepper M, Bernardes GJ, Dougan M, Garcia KC, Baker D (January 2019). “De novo design of potent and selective mimics of IL-2 and IL-15.”. Nature 565 (7738): 186–191. Bibcode: 2019Natur.565..186S. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0830-7. PMC 6521699. PMID 30626941.

- ^ “Another publication in Nature describing the first de novo designed proteins with anti-cancer activity”. Rosetta@home (2020年1月14日). 2020年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ Hutson, Matthew (2020年9月18日). “Scientists Advance on One of Technology's Holy Grails”. The New Yorker 2020年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Neoleukin Therapeutics Announces Submission of Investigational New Drug Application for NL-201 De Novo Protein Immunotherapy Candidate for Cancer”. Neoleukin Therapeutics (2020年12月10日). 2020年12月10日閲覧。

- ^ Simons KT, Bonneau R, Ruczinski I, Baker D (1999). “Ab initio protein structure prediction of CASP III targets using Rosetta”. Proteins Suppl 3: 171–76. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(1999)37:3+<171::AID-PROT21>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 10526365.

- ^ “Interview with David Baker”. Team Picard Distributed Computing (2006年). 2009年2月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年12月23日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: News archive”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2016年). 2016年7月20日閲覧。

- ^ Nauli S, Kuhlman B, Baker D (July 2001). “Computer-based redesign of a protein folding pathway”. Nature Structural Biology 8 (7): 602–05. doi:10.1038/89638. PMID 11427890.

- ^ Kuhlman B, Dantas G, Ireton GC, Varani G, Stoddard BL, Baker D (November 2003). “Design of a novel globular protein fold with atomic-level accuracy”. Science 302 (5649): 1364–68. Bibcode: 2003Sci...302.1364K. doi:10.1126/science.1089427. PMID 14631033.

- ^ Jones DT (November 2003). “Structural biology. Learning to speak the language of proteins”. Science 302 (5649): 1347–48. doi:10.1126/science.1092492. PMID 14631028.

- ^ von Grotthuss M, Wyrwicz LS, Pas J, Rychlewski L (June 2004). “Predicting protein structures accurately”. Science 304 (5677): 1597–99; author reply 1597–99. doi:10.1126/science.304.5677.1597b. PMID 15192202.

- ^ “Articles citing: Kuhlman et al. (2003) 'Design of a novel globular protein fold with atomic-level accuracy'”. ISI Web of Science. 2008年7月10日閲覧。

- ^ “October 2005 molecule of the month: Designer proteins”. RCSB Protein Data Bank. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Research Overview”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2007年). 2008年9月25日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Kuhlman laboratory homepage”. Kuhlman Laboratory. University of North Carolina. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “RosettaDesign web server”. Kuhlman Laboratory. University of North Carolina. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Gray JJ, Moughon SE, Kortemme T, etal (July 2003). “Protein–protein docking predictions for the CAPRI experiment”. Proteins 52 (1): 118–22. doi:10.1002/prot.10384. PMID 12784377.

- ^ Gray JJ, Moughon SE, Kortemme T, etal (July 2003). “Protein–protein docking predictions for the CAPRI experiment”. Proteins 52 (1): 118–22. doi:10.1002/prot.10384. PMID 12784377.

- ^ Schueler-Furman O, Wang C, Baker D (August 2005). “Progress in protein–protein docking: atomic resolution predictions in the CAPRI experiment using RosettaDock with an improved treatment of side-chain flexibility”. Proteins 60 (2): 187–94. doi:10.1002/prot.20556. PMID 15981249.

- ^ Daily MD, Masica D, Sivasubramanian A, Somarouthu S, Gray JJ (2005). “CAPRI rounds 3–5 reveal promising successes and future challenges for RosettaDock”. Proteins 60 (2): 181–86. doi:10.1002/prot.20555. PMID 15981262.

- ^ Méndez R, Leplae R, Lensink MF, Wodak SJ (2005). “Assessment of CAPRI predictions in rounds 3–5 shows progress in docking procedures”. Proteins 60 (2): 150–69. doi:10.1002/prot.20551. PMID 15981261.

- ^ “RosettaDock server”. Rosetta Commons. 2020年3月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Protein–protein docking at Rosetta@home”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Lensink MF, Méndez R, Wodak SJ (December 2007). “Docking and scoring protein complexes: CAPRI 3rd Edition”. Proteins 69 (4): 704–18. doi:10.1002/prot.21804. PMID 17918726.

- ^ Wang C, Schueler-Furman O, Andre I, etal (December 2007). “RosettaDock in CAPRI rounds 6–12”. Proteins 69 (4): 758–63. doi:10.1002/prot.21684. PMID 17671979.

- ^ “Robetta web server”. Baker laboratory. University of Washington. 2019年5月7日閲覧。

- ^ Aloy P, Stark A, Hadley C, Russell RB (2003). “Predictions without templates: new folds, secondary structure, and contacts in CASP5”. Proteins 53 Suppl 6: 436–56. doi:10.1002/prot.10546. PMID 14579333.

- ^ Jauch R, Yeo HC, Kolatkar PR, Clarke ND (2007). “Assessment of CASP7 structure predictions for template free targets”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 57–67. doi:10.1002/prot.21771. PMID 17894330.

- ^ Tress M, Ezkurdia I, Graña O, López G, Valencia A (2005). “Assessment of predictions submitted for the CASP6 comparative modeling category”. Proteins 61 Suppl 7: 27–45. doi:10.1002/prot.20720. PMID 16187345.

- ^ Battey JN, Kopp J, Bordoli L, Read RJ, Clarke ND, Schwede T (2007). “Automated server predictions in CASP7”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 68–82. doi:10.1002/prot.21761. PMID 17894354.

- ^ Chivian D, Kim DE, Malmström L, Schonbrun J, Rohl CA, Baker D (2005). “Prediction of CASP6 structures using automated Robetta protocols”. Proteins 61 Suppl 7: 157–66. doi:10.1002/prot.20733. PMID 16187358.

- ^ Baker D. “David Baker's Rosetta@home journal, message 52902”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Das R, Qian B, Raman S, etal (2007). “Structure prediction for CASP7 targets using extensive all-atom refinement with Rosetta@home”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 118–28. doi:10.1002/prot.21636. PMID 17894356.

- ^ Ovchinnikov, S; Kim, DE; Wang, RY; Liu, Y; DiMaio, F; Baker, D (September 2016). “Improved de novo structure prediction in CASP11 by incorporating coevolution information into Rosetta.”. Proteins 84 Suppl 1: 67–75. doi:10.1002/prot.24974. PMC 5490371. PMID 26677056.

- ^ Baker D. “David Baker's Rosetta@home journal (message 52963)”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月16日閲覧。

- ^ “Foldit forums: How many users does Foldit have? Etc. (message 2)”. University of Washington. 2008年9月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Foldit: Frequently Asked Questions”. fold.it. University of Washington. 2008年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Project list – BOINC”. University of California. 2008年9月8日閲覧。

- ^ Pande Group (2010年). “High Performance FAQ” (FAQ). Stanford University. 2012年9月21日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2011年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ 7im (2010年4月2日). “Re: Answers to: Reasons for not using F@H”. 2011年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ Vijay Pande (2011年8月5日). “Results page updated – new key result published in our work in Alzheimer's Disease”. 2011年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ Pande Group. “Folding@home Diseases Studied FAQ” (FAQ). Stanford University. 2007年10月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2011年9月12日閲覧。

- ^ Vijay Pande (2007年9月26日). “How FAH works: Molecular dynamics”. 2011年9月10日閲覧。

- ^ tjlane (2011年6月9日). “Re: Course grained Protein folding in under 10 minutes”. 2011年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ tjlane (2011年6月9日). “Re: Course grained Protein folding in under 10 minutes”. 2011年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ jmn (2011年7月29日). “Rosetta@home and Folding@home: additional projects”. 2011年9月19日閲覧。

- ^ Pande Group. “Client Statistics by OS”. Stanford University. 2011年10月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Credit overview”. boincstats.com. 2020年3月28日閲覧。

- ^ Malmström L, Riffle M, Strauss CE, etal (April 2007). “Superfamily assignments for the yeast proteome through integration of structure prediction with the gene ontology”. PLOS Biology 5 (4): e76. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050076. PMC 1828141. PMID 17373854.

- ^ Bonneau R (2006年). “World Community Grid Message Board Posts: HPF -> HPF2 transition”. Bonneau Lab, New York University. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “List of Richard Bonneau's publications”. Bonneau Lab, New York University. 2008年7月7日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ Bonneau R. “World Community Grid Message Board Posts”. Bonneau Lab, New York University. 2008年7月4日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “RALPH@home website”. RALPH@home forums. University of Washington. 2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Predictor@home: Developing new application areas for P@H”. The Brooks Research Group. 2008年9月7日閲覧。[リンク切れ]

- ^ Carrillo-Tripp M (2007年). “dTASSER”. The Scripps Research Institute. 2007年7月6日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Credit overview”. boincstats.com. 2020年3月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home”. 2020年3月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: The new credit system explained”. Rosetta@home forums. University of Washington (2006年). 2008年10月8日閲覧。

- ^ “BOINCstats: Project Credit Comparison”. boincstats.com (2008年). 2008年9月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月8日閲覧。

- ^ “Credit divided over projects”. boincstats.com. 2015年2月19日閲覧。

- ^ Das R, Qian B, Raman S, etal (2007). “Structure prediction for CASP7 targets using extensive all-atom refinement with Rosetta@home”. Proteins 69 Suppl 8: 118–28. doi:10.1002/prot.21636. PMID 17894356.

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Predictor of the day archive”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2008年). 2008年9月24日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年10月8日閲覧。

- ^ “Rosetta@home: Protein Folding, Design, and Docking”. Rosetta@home. University of Washington (2008年). 2008年10月8日閲覧。

- Rosetta@homeのページへのリンク