オープンソースソフトウェア

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2024/03/19 13:15 UTC 版)

ライセンス

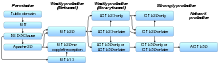

オープンソースライセンスは、オープンソースソフトウェアの定義に従い利用者の利用目的に問わずソフトウェアのソースコードの利用・修正・再頒布を認めるソフトウェアライセンスである。オープンソースライセンスの多くはソフトウェアのソースコードを公開したパーミッシブ・ライセンスもしくはコピーレフト・ライセンスである。パーミッシブ・ライセンスはソフトウェアの利用に最低限の制約のみを課し[33]、コピーレフト・ライセンスはソフトウェアの利用に利用者の自由を制約として義務付ける[34]。ソフトウェアに課せられたライセンスが本当にオープンソースソフトウェアであることを認めるソフトウェアライセンスであるかについて慎重な法的レビューをするべきである[35]。

2018年2月現在、広く使われている、もしくは、著名なコミュニティが採用しているパーミッシブ・ライセンスとしてApache-2.0[36]・BSD-3-Clause[37]・BSD-2-Clause[38]・MIT[39]、コピーレフト・ライセンスのGPLv3[40]・LGPLv3[41]、原作者特権条項のあるMPL-2.0[42]・CDDL-1.0[43]・EPL-2.0[44]が挙げられる[5]。

誓約

オープンソースライセンスは、ライセンサー(作者)の定めた誓約に従う範囲でライセンシー(利用者)にソフトウェアとソースコードの自由な利用を認める。オープンソースソフトウェアの性質上、ソフトウェアやその二次著作物は元の作者でも制御しきれない形で頒布されるため、多くのライセンスでソフトウェアおよびソースコードの利用に際して「無保証 (NO WARRANTY)」と宣言した誓約を記す[45]。それに加えてライセンス毎に異なる誓約(条項・条文)が記す。

著作権表示条項および広告表示条項は、適切な形でソースコードや付属文書に含まれる著作権表示を保持し、つまり二次的著作物を作った者が自分で0から作ったように偽らないことを定める[46]。著作権表示は改変していないソースコードファイルのヘッダのコピーライトを残した上で、ソフトウェアを利用するエンドユーザーに作品元を表示することを求めるApache-2.0や、ソフトウェアのソースコードツリーのCOPYRIGHTファイルに作品元を記すことを要求するMITなどがある。

コピーレフト条項ないし継承条項は、そのライセンスで公開されたソフトウェアを修正して二次創作物として公開する場合に、同じライセンスもしくはそれと同等条件の利用許可を要求するライセンスで公開することを定める[34][47]。同等ライセンスを派生ソフトウェアに課すことで、ライセンスが規程するソースコードの共有文化のコモンズを展開する。派生ソフトウェアに同一ライセンスを要求するGPL・MPL-2.0・CDDL-1.0がある。

原作者特権条項は、原則的には利用者にその事項を許可もしくは禁止するが、原作者が利用する場合にはその限りではないことを定める。原作者は利用者にソフトウェアのソースコードを開示することを要求するMPL-2.0・CDDL-1.0がある。

ガイドライン

オープンソースライセンスは多数のライセンスが存在しているが、オープンソース・イニシアティブ・GNUプロジェクト・Fedoraプロジェクト・Debianプロジェクトなどは対象のソフトウェアライセンスがオープンソースソフトウェアに課すライセンスとして適切であるかの法的レビューを個々に実施している[35]。特にオープンソース・イニシアティブとGNUプロジェクトのライセンスレビューは重要であり、それらの団体のレビューを通ったライセンスをオープンソースライセンスとして用いることが推奨される。

オープンソース・イニシアティブはオープンソースの定義に基づいたライセンスレビューの実施とライセンスの一覧を管理をしている[48][49]。オープンソースのライセンスの中でも主要なライセンスを選定しており、オープンソースソフトウェアにはその主要なライセンスの中からライセンス選択することを推奨している[5]。オープンソースのライセンスと主要ライセンスの一覧は適宜更新されており、過去に承認・推奨されていたライセンスでも現在は非推奨となったライセンスなどもある。

GNUプロジェクトは自由ソフトウェアの定義に基づいた自由ソフトウェアライセンスの一覧を管理している[50]。一覧には自由ソフトウェアの定義に適合しているか、コピーレフト条項を含むか、GPLと互換性があるか、および特記事項を記載している。自由ソフトウェアはそれに応じた異なるライセンスを選択するべきとし、ライセンス選択時の推奨ガイドラインを出している[6]。一般的なソフトウェアではコピーレフト特性をもつGPL、小さなプログラムではコピーレフト特性を持たないApache-2.0、ライブラリではLGPL、サーバソフトウェアではAGPLを推奨している。

Fedoraプロジェクトは同プロジェクトのソフトウェアに課せられるべきソフトウェアライセンスの一覧を管理している[51]。Fedoraの公式パッケージに含まれるソフトウェアはこの一覧にあるソフトウェアライセンスが課せられたものであり、これらのライセンスはフリーソフトウェア財団、オープンソース・イニシアティブおよびRed Hat法務担当が公認したものである[3]。ライセンスの検証はFedoraのメーリングリストで公に検証されている[52]。ただし、コンフィデンシャルな情報を送ることや、ソースコードについての法的な助言を求めるために利用してはならないし、メーリングリストの参加者が法律家や弁護士であることを仮定するべきではない。

DebianプロジェクトはDebianフリーソフトウェアガイドライン (DFSG) に基づいたソフトウェアライセンスの一覧を管理している[53]。Debianの公式パッケージに含まれるソフトウェアは原則としてDebianフリーソフトウェアガイドラインに準拠したソフトウェアライセンスが課せられたものである。Debianフリーソフトウェアガイドラインはオープンソースソフトウェアの定義に符号するものであり、DFSG準拠ライセンスはオープンソースソフトウェアに課すソフトウェアライセンスの一例として参考にできる。

検討課題

ソフトウェアライセンスにはライセンスの互換性がある。異なるライセンスはそれぞれが定める誓約の下にソフトウェアとソースコードを利用することが出来るが、ライセンスによっては自身のソフトウェアの利用に対する誓約だけではなく併用するソフトウェアに対して求める誓約を含む場合があり、その際に複数のソフトウェアのライセンスに互換性がない場合はソフトウェアを併用することが不可能となる。例えば、GNU General Public Licenseは併用するソフトウェアに同一のライセンスを適用することを求めているため、同ライセンスと商用ソフトウェアのクローズドソースを求めるライセンスは併用出来ない。フリーソフトウェア財団はGPLのコピーレフト誓約違反に対して幾度も訴訟を起こしている。

2000年代前半、オープンソースソフトウェアのライセンスは多数の独自ライセンスが策定され、よく似た条文で一部分だけ異なるという有象無象のライセンスがいたずらに作られていったことを問題視し、その事象はライセンスの氾濫と呼ばれ批判の対象となった[55]。ライセンスの氾濫はライセンス製作者の虚栄心を満たすだけの無害なものではなく、オープンソースソフトウェアに課せられたライセンスの内容を精査しなければならない利用者を疲弊させる有害なものであった。オープンソース・イニシアティブは2006年にこの問題を解決するためライセンス氾濫問題プロジェクト (License Proliferation Project) を立ち上げ[56]、ライセンスレビューを通して承認ライセンスを選定することでライセンスの氾濫を抑えた歴史がある[57]。ライセンスの氾濫を再発させないため、オープンソースソフトウェアのライセンスは既存のオープンソースライセンスを採用することが推奨される[5][6]。ライセンスの作成者は新規ライセンスの必要性について慎重な検討を経て策定に至り[58]、ライセンスを承認する団体は新規のライセンスが既存のライセンスと本質的な差異がない場合は承認しない判断を下している[59]。

ライセンスの継承条文を伴うオープンソースライセンスが課せられたソフトウェアは、その継承条文に基づき、ソフトウェアのソースコードを利用、修正したソフトウェアのソフトウェアライセンスを同等条件のものとするよう縛る。このライセンスの縛りはソースコードの二次利用、三次利用と伝播し、ライセンスがウイルスのように感染していくことからウイルス性ライセンス(ライセンス感染)と呼ばれる[60]。ライセンス感染するライセンスの例としては、GPL (コピーレフト条文)やCC BY-SA (SA条項)がある。ライセンス感染の影響は元となったソフトウェアライセンスの内容に依るが、GNU GPLのコピーレフト条項のようにソースコードの公開を義務とするものや[34]、CC BY-SAのSA条項ように同等条件のライセンスを強制するだけ(ソースコードの公開を求めるかどうかは別条文に依る)のものがある[61]。

パブリックドメインによる著作権の放棄は著作権法の下に完全に認められたという実績(判決)は存在しておらず、法的な判断が不明瞭である[62]。ソースコード作成者が著作権を放棄する意図でパブリックドメイン以下で公開していたソースコードに対して、ソースコード作成者が考えを変えて著作権の保持を主張してソースコードの二次利用者を訴えた場合に、サブマリン特許のように見解を翻して権利を行使することの是非という道徳的な観点は別として、著作権の放棄の有効性について著作権法の下にどのような判断がなされるのか明確になっていない。つまり、パブリックドメインはソースコード作成者の当初の意図に反して著作権の放棄はできておらず、著作権の保持を根拠にしたソースコードの二次利用者に対する訴えは有効であるとされる可能性がある。そのような不確定性のため、オープンソース・イニシアティブはパブリックドメインに相当するCC0を有効なオープンソースライセンスとして承認していない[63]。一方で、フリーソフトウェア財団はCC0を有効なフリーソフトウェアライセンスとして承認している[64]。

- ^ a b c d United States Department of Defense (2009年10月16日). “Defining Open Source Software (OSS)”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。 “defines OSS as "software for which the human-readable source code is available for use, study, re-use, modification, enhancement, and re-distribution by the users of that software"”

- ^ a b Landley, Rob (2009年5月23日). “notes-2009”. landley.net. 2015年12月2日閲覧。 “So if open source used to be the norm back in the 1960's and 70's, how did this _change_? Where did proprietary software come from, and when, and how? How did Richard Stallman's little utopia at the MIT AI lab crumble and force him out into the wilderness to try to rebuild it? Two things changed in the early 80's: the exponentially growing installed base of microcomputer hardware reached critical mass around 1980, and a legal decision altered copyright law to cover binaries in 1983.”

- ^ a b Fedora. “Licensing:Main Overview”. 2018年2月20日閲覧。 “This list is based on the licenses approved by the Free Software Foundation , OSI and consultation with Red Hat Legal.”

- ^ a b c d United States Department of Defense (2009年10月16日). “Q: What are antonyms for open source software?”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e Open Source Initiative. “Licenses & Standards”. 2018年2月8日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d GNU Project (2018年1月1日). “How to choose a license for your own work”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ “What is Free Software?”. GNU Project (1998年1月26日). 2018年3月10日閲覧。

- ^ Karl Fogel (2016年). “Producing Open Source Software - How to Run a Successful Free Software Project”. O'Reilly Media. 2016年4月11日閲覧。

- ^ History of the Open Source Initiative

- ^ Technology In Government, 1/e. Jaijit Bhattacharya. (2006). p. 25. ISBN 978-81-903397-4-2

- ^ annr (2017年5月16日). “What is open source, and what is the Open Source Initiative?”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ Open Source Initiative (2007年3月22日). “The Open Source Definition”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ Open Source Initiative (2007年3月22日). “Can I call my program "Open Source" even if I don't use an approved license?”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ GNU Project (2018年1月1日). “What is free software?”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e Richard Stallman (2016年11月18日). “Why Open Source misses the point of Free Software”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ 総務省. “2 OSSの影響 : 平成18年版 情報通信白書”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。 “Open Source Initiative(OSI)が定めた「The Open Source Definition(OSD)」と呼ばれる定義を満たすソフトウェアである”

- ^ “Open Source Certification:Press Releases”. Open Source Initiative (1999年6月). 2018年3月1日閲覧。

- ^ “商標照会(固定アドレス) 商標公報4553488”. 特許情報プラットフォーム. 2018年3月25日閲覧。

- ^ “オープンソース商標について”. オープンソースグループ・ジャパン (2003年). 2018年3月1日閲覧。

- ^ Dana Blankenhorn (2006年12月7日). “Is SugarCRM open source?”. 2018年2月15日閲覧。

- ^ Tiemann, Michael (2007年6月21日). “Will The Real Open Source CRM Please Stand Up?”. Open Source Initiative. 2008年1月4日閲覧。

- ^ Vance, Ashlee (2007年7月25日). “SugarCRM trades badgeware for GPL 3”. The Register 2008年9月8日閲覧。

- ^ “The Big freedesktop.org Interview”. OSNews (2003年11月24日). 2018年3月26日閲覧。

- ^ Lohr, Steve (2007年1月22日). “Group Formed to Support Linux as Rival to Windows”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 2016年4月14日閲覧。

- ^ “Linux lab lands Torvalds”. CNET. 2016年4月14日閲覧。

- ^ “Industry Leaders Announce Open Platform for Mobile Devices”. Open Handset Alliance (2007年11月5日). 2007年11月5日閲覧。

- ^ “Open Handset Alliance members page”. Open Handset Alliance (2007年11月5日). 2007年11月5日閲覧。

- ^ “Developers”. Open Handset Alliance (2007年11月5日). 2007年11月5日閲覧。

- ^ “Alibaba: Google just plain wrong about our OS”. CNET News (2012年9月15日). 2018年3月26日閲覧。

- ^ Amadeo, Ron (2013年10月21日). “Google’s iron grip on Android: Controlling open source by any means necessary”. Ars Technica (p.3) 2013年12月1日閲覧。

- ^ “About The Licenses”. Creative Commons. 2018年3月2日閲覧。

- ^ “Creative Commons FAQ: Can I use a Creative Commons license for software?”. Creative Commons. 2018年3月26日閲覧。

- ^ “What is a "permissive" Open Source license?”. Open Source Initiative. 2018年3月26日閲覧。 “A "permissive" license is simply a non-copyleft open source license – one that guarantees the freedoms to use, modify, and redistribute, but that permits proprietary derivatives.”

- ^ a b c “What is Copyleft?”. Free Software Foundation (2018年1月1日). 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ a b United States Department of Defense (2009年10月16日). “Defining Open Source Software (OSS)”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。 “Careful legal review is required to determine if a given license is really an open source software license.”

- ^ “Apache License, Version 2.0”. GNU Project (2018年2月10日). 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ “Modified BSD license”. GNU Project (2018年2月10日). 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ “FreeBSD license”. GNU Project (2018年2月10日). 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ “X11 License”. GNU Project (2018年2月10日). 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ “GNU General Public License (GPL) version 3”. GNU Project (2018年2月10日). 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ “GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL) version 3”. GNU Project (2018年2月10日). 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ “MPL 2.0 FAQ”. Mozilla. 2018年2月9日閲覧。 “The MPL is a simple copyleft license.”

- ^ Rami Sass. “Top 10 Common Development and Distribution License (CDDL) Questions Answered”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。 “The CDDL is considered a weak copyleft license.”

- ^ “Eclipse Public License Version 2.0”. GNU Project (2018年2月10日). 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ Pieter Gunst (2015年8月15日). “Open Source Software: a legal guide”. LawGives. 2018年3月8日閲覧。 “Most open source licenses do not provide any warranties, but instead will provide the software "AS IS."”

- ^ Dennis Clark (2015年12月4日). “OSS Attribution Obligations”. nexB. 2018年3月8日閲覧。

- ^ “Share Alike”. wiki.creativecommons.org. 2011年8月29日閲覧。 “The Share Alike aspect requires all derivatives of a work to be licensed under the same (or a compatible) license as the original.”

- ^ Open Source Initiative. “The Licence Review Process”. 2018年2月8日閲覧。

- ^ Open Source Initiative. “Open Source Licenses by Category”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ GNU Porject (2018年2月10日). “Various Licenses and Comments about Them”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ Fedora (2017-11--06). “Licensing:Main”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ Fedora (2017年11月6日). “Discussion of Licensing”. 2018年2月15日閲覧。

- ^ Debian (2018年2月4日). “License information”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ The Free-Libre / Open Source Software (FLOSS) License Slide by David A. Wheeler on September 27, 2007

- ^ Martin Michlmayr (2008年8月21日). “OSI and License Proliferation”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ Open Source Initiative. “The Licence Proliferation Project”. 2011年5月10日閲覧。

- ^ Open Source Initiative. “The Licence Review Process”. 2018年2月8日閲覧。

- ^ “Common Development and Distribution License (CDDL) Description and High-Level Summary of Changes”. sun.com. 2005年2月14日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2018年3月25日閲覧。

- ^ “OSI Board Meeting Minutes, Wednesday, March 4, 2009”. Open Source Initiative. 2011年4月1日閲覧。 “It's no different from dedication to the public domain. ... Recommend: Reject”

- ^ “Speech Transcript - Craig Mundie, The New York University Stern School of Business” (2001年5月3日). 2005年6月21日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2011年2月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Share Alike”. Creative Commons. 2017年8月13日閲覧。

- ^ webmink (2017年7月28日). “Public Domain Is Not Open Source”. 2018年2月25日閲覧。

- ^ “OSI Board Meeting Minutes, Wednesday, March 4, 2009” (2009年3月4日). 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ GNU Project (2018年2月10日). “CC0”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ Raymond, Eric S. (1999). The Cathedral and the Bazaar. O'Reilly Media. p. 30. ISBN 1-56592-724-9

- ^ Kent Roberts (2014年9月16日). “A Brief History of Linux/Open Source Distributions”. atlantic.net. 2018年3月15日閲覧。

- ^ Pichai, Sundar (2009年7月7日). “Introducing the Google Chrome OS”. Official Google Blog. Google, Inc.. 2012年7月11日閲覧。

- ^ Shankland, Stephen (2012年3月30日). “Google's Go language turns one, wins a spot at YouTube: The lower-level programming language has matured enough to sport the 1.0 version number. And it's being used for real work at Google.”. CBS Interactive Inc (2012-03-30発行) 2017年8月6日閲覧. "Google has released version 1 of its Go programming language, an ambitious attempt to improve upon giants of the lower-level programming world such as C and C++."

- ^ catamorphism (2012年1月20日). “Mozilla and the Rust community release Rust 0.1 (a strongly-typed systems programming language with a focus on memory safety and concurrency)”. 2012年2月6日閲覧。

- ^ Platforms State of the Union, Session 102, Apple Worldwide Developers Conference, June 2, 2014

- ^ “Swift Has Reached 1.0” (2014年9月9日). 2014年9月10日閲覧。

- ^ Popp, Dr. Karl Michael; Meyer, Ralf (2010). Profit from Software Ecosystems: Business Models, Ecosystems and Partnerships in the Software Industry. Norderstedt, Germany: Books on Demand. ISBN 9783839169834

- ^ Wheeler, David A. (2009年2月). “F/LOSS is Commercial Software”. Technology Innovation Management Review. Talent First Network. 2016年6月18日閲覧。

- ^ Popp, Dr. Karl Michael (2015). Best Practices for commercial use of open source software. Norderstedt, Germany: Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3738619096

- ^ Solatan, Jean (2011). Advances in software economics: A reader on business models and Partner Ecosystems in the software industry. Norderstedt, Germany: BOD. ISBN 978-3-8448-0405-8

- ^ Germain, Jack M. (2013年11月5日). “FOSS in the Enterprise: To Pay or Not to Pay?”. LinuxInsider. ECT News Network, Inc.. 2016年6月18日閲覧。

- ^ Byfield, Bruce (2005年9月21日). “Google's Summer of Code concludes”. linux.com. 2016年6月18日閲覧。 “DiBona said that the SOC was designed to benefit everyone involved in it. Students had the chance to work on real projects, rather than academic ones, and to get paid while gaining experience and making contacts. FOSS projects benefited from getting new code and having the chance to recruit new developers.”

- ^ Lunduke, Bryan (2013年8月7日). “Open source gets its own crowd-funding site, with bounties included - Bountysource is the crowd-funding site the open source community has been waiting for.”. networkworld.com. 2013年8月10日閲覧。 “Many open source projects (from phones to programming tools) have taken to crowd-funding sites (such as Kickstarter and indiegogo) in order to raise the cash needed for large-scale development. And, in some cases, this has worked out quite well.”

- ^ “TTimo/doom3.gpl”. GitHub (2012年4月7日). 2013年8月10日閲覧。 “Doom 3 GPL source release [...] This source release does not contain any game data, the game data is still covered by the original EULA and must be obeyed as usual.”

- ^ Hustvedt, Eskild (2009年2月8日). “Our new way to meet the LGPL”. 2009年2月20日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2011年3月9日閲覧。 “You can use a special keyword $ORIGIN to say 'relative to the actual location of the executable'. Suddenly we found we could use -rpath $ORIGIN/lib and it worked. The game was loading the correct libraries, and so was stable and portable, but was also now completely in the spirit of the LGPL as well as the letter!”

- ^ Naramore, Elizabeth (2011年3月4日). “SourceForge.net Donation System”. SourceForge. Slashdot Media. 2017年10月16日閲覧。

- ^ “SourceForge Reports Second Quarter Fiscal 2009 Financial Results”. 2015年6月3日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2018年2月15日閲覧。

- ^ Raymond, Eric Steven. “The Cathedral and the Bazaar”. 2012年4月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Open Sources: Voices from the Open Source Revolution”. O'Reilly Media. 2010年8月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Open Sources 2.0”. at O'Reilly Media. 2017年9月8日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年10月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Revolution OS (2001)”. IMDb.com, Inc.. 2018年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Free Software Movement”. The Free Software Foundation (2014年4月12日). 2018年4月4日閲覧。

- ^ Bertle King, Jr. (2017年2月21日). “Open Source vs. Free Software: What's the Difference and Why Does It Matter?”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ “Various Licenses and Comments about Them - Sybase Open Watcom Public License version 1.0 (#Watcom)”. gnu.org. 2015年12月23日閲覧。 “This is not a free software license. It requires you to publish the source code publicly whenever you “Deploy” the covered software, and “Deploy” is defined to include many kinds of private use.”

- ^ “Richard Stallman explains the new GPL provisions to block "tivoisation"”. 2018年2月15日閲覧。

- ^ “InformationWeek: TiVo Warns Investors New Open Source License Could Hurt Business”. 2018年2月15日閲覧。

- ^ マイクロソフト. “Shared Source Initiative”. 2018年2月15日閲覧。 “the Shared Source Initiative Microsoft licenses product source code to qualified customers, enterprises, governments, and partners for debugging and reference purposes”

- ^ Stephen R. Walli (2005年3月24日). “Perspectives on the Shared Source Initiative”. 2018年2月15日閲覧。

- ^ Mary Jo Foley (2007年10月16日). “Microsoft gets the open-source licensing nod from the OSI”. 2018年2月15日閲覧。

- ^ Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. (2005年). “SCEA Shared Source License 1.0”. 2007年1月2日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2018年2月14日閲覧。

- ^ Fedora (2017年11月6日). “Software License List”. 2018年2月14日閲覧。

- ^ Irina Guseva (2009年5月26日). “Bad Economy Is Good for Open Source”. 2018年2月15日閲覧。

- ^ Joab Jackson (2011年11月3日). “Open Source vs. Proprietary Software”. PCWorld Business Center. Pcworld.com. 2018年2月15日閲覧。

- ^ Martin LaMonica (2004年2月12日). “Pandora's box for open source - CNET News”. News.cnet.com. 2012年11月4日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2012年3月25日閲覧。

- ^ Seltzer, Larry (2004年5月4日). “Is Open-Source Really Safer?”. PCMag.com. 2012年3月25日閲覧。

- ^ WIRED STAFF (2004年12月14日). “LINUX: FEWER BUGS THAN RIVALS”. 2018年2月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Coverity Scan Report Finds Open Source Software Quality Outpaces Proprietary Code for the First Time”. Coverity, Inc. (2014年4月15日). 2018年4月5日閲覧。

- ^ Bruce Perens (1999年2月17日). “It's Time to Talk about Free Software Again”. 2018年3月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Linux and the GNU Project”. 2008年12月13日閲覧。

- ^ “GNU/Linux FAQ”. 2008年12月13日閲覧。

- ^ Stephen Benson (12 May 1994). "Linux/GNU in EE Times". Newsgroup: comp.os.linux.misc. Usenet: 178@scribendum.win-uk.net. 2008年1月31日閲覧。

- ^ Govind, Puru (2006年5月). “The "GNU/Linux" and "Linux" Controversy”. 2008年10月26日閲覧。

- ^ “Linux - The Jargon File, version 4.4.8”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。 “This claim is a proxy for an underlying territorial dispute; [..] RMS and friends wrote many of its user-level tools. Neither this theory nor the term GNU/Linux has gained more than minority acceptance”

- ^ Christopher Tozzi (2013年10月30日). “The Halloween Documents: Microsoft's Anti-Linux Strategy 15 Years Later”. Channel Futures. 2018年4月4日閲覧。

- ^ “De Nederlandse Open Source Pagina's”. De Nederlandse Open Source Groep (1998年11月5日). 2018年4月4日閲覧。

- ^ “Microsoft Responds to the Open Source Memo Regarding the Open Source Model and Linux”. Windows NT Server 4.0 website. マイクロソフト (1998年11月5日). 1999年10月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2012年6月2日閲覧。

- ^ a b Raymond, Eric. “Halloween VII: Survey Says”. 2018年4月4日閲覧。

- ^ Raymond, Eric. “Halloween Document II”. 2018年4月4日閲覧。

- ^ Raymond, Eric. “Halloween Document I”. 2018年4月4日閲覧。

- ^ “News Service”. P&L Communications (1998年12月30日). 1999年4月7日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2018年4月2日閲覧。

- ^ “Microsoft exec dissects Linux's 'weak value proposition'”. ZDNet (1999年3月4日). 1999年5月8日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2018年4月2日閲覧。

- ^ Raymond, Eric. “Halloween Document VI”. 2018年4月4日閲覧。

- ^ “SCO Establishes SCOsource to License Unix Intellectual Property”. 2010年1月2日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2018年4月8日閲覧。

- ^ Montalbano, Elizabeth (2007年8月15日). “Novell Won't Pursue Unix Copyrights”. PC World 2007年9月4日閲覧。

- ^ Markoff, John (2007年8月11日). “Judge Says Unix Copyrights Rightfully Belong to Novell”. New York Times 2007年8月15日閲覧。

- ^ Richard Stallman (2016年11月18日). “FLOSS and FOSS”. 2018年2月9日閲覧。

オープンソースソフトウェアと同じ種類の言葉

- オープンソースソフトウェアのページへのリンク