DDIT3

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2023/10/28 07:03 UTC 版)

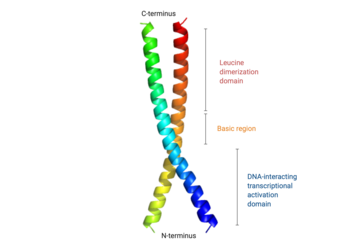

構造

C/EBPファミリーのタンパク質はC末端に保存された塩基性ロイシンジッパードメイン(bZIP)が存在し、この領域はDNA結合能を持つホモ二量体の形成、または他のタンパク質やC/EBPファミリーの他のメンバーとのヘテロ二量体の形成に必要である[7]。

調節と機能

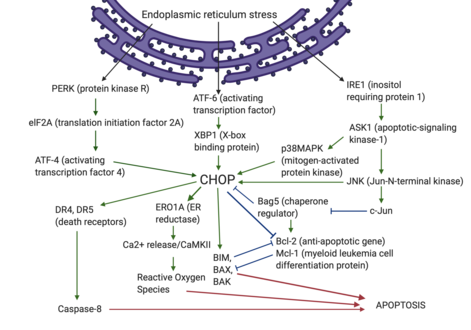

CHOPは上流と下流でさまざまな調節的相互作用を行っており、病原性微生物やウイルスの感染、アミノ酸枯渇、小胞体ストレスなどさまざま刺激によって引き起こされるアポトーシス、ミトコンドリアストレス、神経疾患やがんに重要な役割を果たしている。

正常な生理的条件下では、CHOPは非常に低レベルで普遍的に存在している[8]。しかしながら、小胞体ストレス条件下ではCHOPの発現はさまざまな細胞種で急上昇し、アポトーシス経路の活性化を伴う[9]。こうした過程は、PERK、ATF6、IRE1αの3つの因子によって主に調節されている[10][11]。

上流の調節経路

小胞体ストレス下では、CHOPは統合的ストレス応答経路の活性化を介して誘導される。統合的ストレス応答では、翻訳開始因子eIF2αのリン酸化、そして転写因子ATF4の誘導が行われ[12]、CHOPなど標的遺伝子のプロモーターに収束する。

統合的ストレス応答、そしてCHOPの発現は、次の因子によって誘導される。

- アミノ酸枯渇(GCN2を介して)[13]

- ウイルス感染(PKRを介して)[14]

- 鉄の欠乏(HRIを介して)[15]

- 小胞体でのフォールディングしていない、または誤ってフォールディングしたタンパク質の蓄積によるストレス(PERKを介して)[16]

小胞体ストレス下では、活性化された膜貫通タンパク質ATF6は核へ移行してATF/cAMP応答エレメント(ATF/cAMP response element)や小胞体ストレス応答エレメント(ER stress-response element)と相互作用し[17]、UPR(unfolded protein response)に関与するいくつかの遺伝子(CHOP、XBP1など)の転写を誘導する[18][19]。このようにATF6はCHOPやXBP1の転写を活性化し、XBP1もまたCHOPの発現をアップレギュレーションする[20]。

小胞体ストレスは膜貫通タンパク質IRE1αの活性も刺激する[21]。IRE1αは活性化に伴ってXBP1のmRNAのイントロンをスプライシングすることで成熟型で活性型のXBP1タンパク質の産生をもたらし[22]、CHOPの発現をアップレギュレーションする[23][24][25]。IRE1αはASK1の活性化も刺激する。その後ASK1はJNKやp38MAPKといった下流のキナーゼを活性化し[26]、CHOPとともにアポトーシスの誘導に参加する[27]。p38MAPKファミリーのタンパク質はCHOPのSer78とSer81をリン酸化し、細胞のアポトーシスを誘導する[28]。JNK阻害剤はCHOPのアップレギュレーションを抑制することが示されており、JNKの活性化もCHOP濃度の調節に関与していることが示唆される[29]。

下流の経路

ミトコンドリア依存的経路を介したアポトーシスの誘導

CHOPは転写因子として、Bcl-2ファミリーやGADD34、TRB3をコードする遺伝子など、多くの抗アポトーシス遺伝子やアポトーシス促進遺伝子の発現を調節する[30][31]。CHOP誘導性アポトーシス経路において、CHOPはBcl-2ファミリーの抗アポトーシスタンパク質(BCL2、BCL-XL、MCL1、BCL-W)やアポトーシス促進タンパク質(BAK、BAX、BOK、BIM、PUMAなど)の発現を調節する[32][33]。

小胞体ストレス下では、CHOPは転写アクチベーターもしくはリプレッサーのいずれかとして機能する。CHOPはbZIPドメインを介した相互作用によって他のC/EBPファミリー転写因子とヘテロ二量体を形成し、C/EBPファミリー転写因子が担う遺伝子発現を阻害するとともに、12–14 bpの特異的シス作用エレメントを含む他の遺伝子の発現を亢進する[34]。CHOPは抗アポトーシス性のBCL2の発現をダウンレギュレーションし、アポトーシス促進性タンパク質(BIM、BAK、BAX)の発現をアップレギュレーションする[35][36]。BAXとBAKのオリゴマー化はミトコンドリアからのシトクロムcやアポトーシス誘導因子(AIF)の放出を引き起こし、最終的には細胞死を引き起こす[37]。

TRB3は、小胞体ストレスによって誘導される転写因子ATF4-CHOPによってアップレギュレーションされる[38]。CHOPはTRB3と相互作用し、アポトーシスの誘導に寄与する[39][40][41]。TRB3の発現はアポトーシス促進作用を有するため[42][43]、CHOPはTRB3の発現のアップレギュレーションを介したアポトーシスの調節も行っていることとなる。

デスレセプター経路を介したアポトーシスの誘導

デスレセプターを介したアポトーシスはデスリガンド(Fas、TNF、TRAIL)とデスレセプターの活性化を介して行われる。活性化に伴って、受容体タンパク質やFADDは細胞死誘導シグナル伝達複合体(DISC)を形成し、下流のカスパーゼカスケードを活性化してアポトーシスを誘導する[44]。

PERK-ATF4-CHOP経路は、デスレセプターDR4、DR5の発現をアップレギュレーションすることでアポトーシスを誘導する。CHOPのN末端ドメインはリン酸化された転写因子JUNと複合体を形成し、DR4やDR5の発現を調節する[44][45]。長期的な小胞体ストレス条件下では、PERK-CHOP経路の活性化によってDR5タンパク質レベルが上昇し、DISCの形成が加速される。それによってカスパーゼ-8が活性化され、アポトーシスが引き起こされる[46][47]。

その他の下流経路を介したアポトーシスの誘導

CHOPは、ERO1α遺伝子の発現の増加を介してのアポトーシスの媒介も行う[10]。ERO1αは小胞体での過酸化水素の産生を触媒する。小胞体が極めて酸化的状態になると過酸化水素が細胞質に漏出し、活性酸素種の産生、一連のアポトーシス応答や免疫応答が誘導される[10][48][49][50]。

CHOPの過剰発現は細胞周期の停止を引き起こし、アポトーシスをもたらす。同時に、CHOPによるアポトーシスの誘導によって細胞周期調節タンパク質p21の発現が阻害されることでも、細胞死は開始される。p21は細胞周期のG1期の進行を阻害するとともに、アポトーシス促進因子の活性の調節も行う。CHOPとp21との関係は、細胞の状態が小胞体ストレスへの適応からアポトーシス促進活性へと変化する過程に関係している可能性がある[51]。

近年の研究では、前立腺がんではBAG5が過剰発現しており、小胞体ストレス誘導性のアポトーシスを阻害していることが示されている[52]。BAG5の過剰発現はCHOPとBAXの発現を減少させ、BCL2の発現を増加させる[52]。BAG5の過剰発現によって、PERK-eIF2-ATF4経路が抑制され、IRE1-XBP1経路の活性が亢進することで、UPR時の小胞体ストレス誘導性アポトーシスが阻害される[53]。

相互作用

DDIT3(CHOP)は次に挙げる因子と相互作用することが示されている。

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000175197 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000025408 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ “Induction by ionizing radiation of the gadd45 gene in cultured human cells: lack of mediation by protein kinase C”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 11 (2): 1009–16. (February 1991). doi:10.1128/MCB.11.2.1009. PMC 359769. PMID 1990262.

- ^ a b c “Entrez Gene: DDIT3 DNA-damage-inducible transcript 3”. 2022年9月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Stress-induced binding of the transcriptional factor CHOP to a novel DNA control element”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 16 (4): 1479–89. (April 1996). doi:10.1128/MCB.16.4.1479. PMC 231132. PMID 8657121.

- ^ “CHOP, a novel developmentally regulated nuclear protein that dimerizes with transcription factors C/EBP and LAP and functions as a dominant-negative inhibitor of gene transcription”. Genes & Development 6 (3): 439–53. (March 1992). doi:10.1101/gad.6.3.439. PMID 1547942.

- ^ “A non-canonical pathway regulates ER stress signaling and blocks ER stress-induced apoptosis and heart failure”. Nature Communications 8 (1): 133. (July 2017). Bibcode: 2017NatCo...8..133Y. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00171-w. PMC 5527107. PMID 28743963.

- ^ a b c “Role of ERO1-alpha-mediated stimulation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor activity in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis”. The Journal of Cell Biology 186 (6): 783–92. (September 2009). doi:10.1083/jcb.200904060. PMC 2753154. PMID 19752026.

- ^ “Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress”. Cell Death and Differentiation 11 (4): 381–9. (April 2004). doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401373. PMID 14685163.

- ^ “ER stress and diseases”. The FEBS Journal 274 (3): 630–58. (February 2007). doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05639.x. PMID 17288551.

- ^ “GRP78 and CHOP modulate macrophage apoptosis and the development of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis”. The Journal of Pathology 239 (4): 411–25. (August 2016). doi:10.1002/path.4738. PMID 27135434.

- ^ “Endoplasmic reticulum stress implicated in chronic traumatic encephalopathy”. Journal of Neurosurgery 124 (3): 687–702. (March 2016). doi:10.3171/2015.3.JNS141802. PMID 26381255.

- ^ “Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the pathogenesis of fibrotic disease”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 128 (1): 64–73. (January 2018). doi:10.1172/JCI93560. PMC 5749533. PMID 29293089.

- ^ “The Role of the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP Signaling Pathway in Tumor Progression During Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress”. Current Molecular Medicine 16 (6): 533–44. (2016). doi:10.2174/1566524016666160523143937. PMC 5008685. PMID 27211800.

- ^ “ER stress-induced cell death mechanisms”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1833 (12): 3460–3470. (December 2013). doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.028. PMC 3834229. PMID 23850759.

- ^ “Antiapoptotic roles of ceramide-synthase-6-generated C16-ceramide via selective regulation of the ATF6/CHOP arm of ER-stress-response pathways”. FASEB Journal 24 (1): 296–308. (January 2010). doi:10.1096/fj.09-135087. PMC 2797032. PMID 19723703.

- ^ “Apelin-13 Alleviates Early Brain Injury after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage via Suppression of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-mediated Apoptosis and Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption: Possible Involvement of ATF6/CHOP Pathway”. Neuroscience 388: 284–296. (September 2018). doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.07.023. PMID 30036660.

- ^ “ATF6 activated by proteolysis binds in the presence of NF-Y (CBF) directly to the cis-acting element responsible for the mammalian unfolded protein response”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 20 (18): 6755–67. (September 2000). doi:10.1128/mcb.20.18.6755-6767.2000. PMC 86199. PMID 10958673.

- ^ “IRE1alpha kinase activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to determine divergent cell fates”. Cell 138 (3): 562–75. (August 2009). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.017. PMC 2762408. PMID 19665977.

- ^ “XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor”. Cell 107 (7): 881–91. (December 2001). doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. PMID 11779464.

- ^ “The unfolded protein response: integrating stress signals through the stress sensor IRE1α”. Physiological Reviews 91 (4): 1219–43. (October 2011). doi:10.1152/physrev.00001.2011. hdl:10533/135654. PMID 22013210.

- ^ “Transcription Factor C/EBP Homologous Protein in Health and Diseases”. Frontiers in Immunology 8: 1612. (2017). doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01612. PMC 5712004. PMID 29230213.

- ^ “Cell death and endoplasmic reticulum stress: disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities”. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 7 (12): 1013–30. (December 2008). doi:10.1038/nrd2755. PMID 19043451.

- ^ “Stress-induced phosphorylation and activation of the transcription factor CHOP (GADD153) by p38 MAP Kinase”. Science 272 (5266): 1347–9. (May 1996). Bibcode: 1996Sci...272.1347W. doi:10.1126/science.272.5266.1347. PMID 8650547.

- ^ “How IRE1 reacts to ER stress”. Cell 132 (1): 24–6. (January 2008). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.017. PMID 18191217.

- ^ “Attenuation of CHOP-mediated myocardial apoptosis in pressure-overloaded dominant negative p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase mice”. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 27 (5): 487–96. (2011). doi:10.1159/000329970. PMID 21691066.

- ^ a b “Tunicamycin enhances human colon cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis by JNK-CHOP-mediated DR5 upregulation and the inhibition of the EGFR pathway”. Anti-Cancer Drugs 28 (1): 66–74. (January 2017). doi:10.1097/CAD.0000000000000431. PMID 27603596.

- ^ “UPR induces transient burst of apoptosis in islets of early lactating rats through reduced AKT phosphorylation via ATF4/CHOP stimulation of TRB3 expression”. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 300 (1): R92-100. (January 2011). doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00169.2010. PMID 21068199.

- ^ “The transcription factor CHOP, a central component of the transcriptional regulatory network induced upon CCl4 intoxication in mouse liver, is not a critical mediator of hepatotoxicity”. Archives of Toxicology 88 (6): 1267–80. (June 2014). doi:10.1007/s00204-014-1240-8. hdl:10533/127482. PMID 24748426.

- ^ “CHOP potentially co-operates with FOXO3a in neuronal cells to regulate PUMA and BIM expression in response to ER stress”. PLOS ONE 7 (6): e39586. (2012-06-28). Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...739586G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039586. PMC 3386252. PMID 22761832.

- ^ “Neuronal apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress is regulated by ATF4-CHOP-mediated induction of the Bcl-2 homology 3-only member PUMA”. The Journal of Neuroscience 30 (50): 16938–48. (December 2010). doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1598-10.2010. PMC 6634926. PMID 21159964.

- ^ “Stress-induced binding of the transcriptional factor CHOP to a novel DNA control element”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 16 (4): 1479–89. (April 1996). doi:10.1128/mcb.16.4.1479. PMC 231132. PMID 8657121.

- ^ “Cell death induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress”. The FEBS Journal 283 (14): 2640–52. (July 2016). doi:10.1111/febs.13598. PMID 26587781.

- ^ “The endoplasmic reticulum stress-C/EBP homologous protein pathway-mediated apoptosis in macrophages contributes to the instability of atherosclerotic plaques”. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 30 (10): 1925–32. (October 2010). doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.206094. PMID 20651282.

- ^ “Interrogating the relevance of mitochondrial apoptosis for vertebrate development and postnatal tissue homeostasis”. Genes & Development 30 (19): 2133–2151. (October 2016). doi:10.1101/gad.289298.116. PMC 5088563. PMID 27798841.

- ^ “TRB3 is stimulated in diabetic kidneys, regulated by the ER stress marker CHOP, and is a suppressor of podocyte MCP-1”. American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology 299 (5): F965-72. (November 2010). doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00236.2010. PMC 2980398. PMID 20660016.

- ^ “Loss of C/EBP-β LIP drives cisplatin resistance in malignant pleural mesothelioma”. Lung Cancer 120: 34–45. (June 2018). doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.03.022. PMID 29748013.

- ^ “HDAC4 protects cells from ER stress induced apoptosis through interaction with ATF4”. Cellular Signalling 26 (3): 556–63. (March 2014). doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.11.026. PMID 24308964.

- ^ “TRB3, a novel ER stress-inducible gene, is induced via ATF4-CHOP pathway and is involved in cell death”. The EMBO Journal 24 (6): 1243–55. (March 2005). doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600596. PMC 556400. PMID 15775988.

- ^ “TRB3: a tribbles homolog that inhibits Akt/PKB activation by insulin in liver”. Science 300 (5625): 1574–7. (June 2003). Bibcode: 2003Sci...300.1574D. doi:10.1126/science.1079817. PMID 12791994.

- ^ “TRB3 reverses chemotherapy resistance and mediates crosstalk between endoplasmic reticulum stress and AKT signaling pathways in MHCC97H human hepatocellular carcinoma cells”. Oncology Letters 15 (1): 1343–1349. (January 2018). doi:10.3892/ol.2017.7361. PMC 5769383. PMID 29391905.

- ^ a b c “DDIT3 and KAT2A Proteins Regulate TNFRSF10A and TNFRSF10B Expression in Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-mediated Apoptosis in Human Lung Cancer Cells”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 290 (17): 11108–18. (April 2015). doi:10.1074/jbc.M115.645333. PMC 4409269. PMID 25770212.

- ^ “Neddylation Inhibition Activates the Extrinsic Apoptosis Pathway through ATF4-CHOP-DR5 Axis in Human Esophageal Cancer Cells”. Clinical Cancer Research 22 (16): 4145–57. (August 2016). doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2254. PMID 26983464.

- ^ “Opposing unfolded-protein-response signals converge on death receptor 5 to control apoptosis”. Science 345 (6192): 98–101. (July 2014). Bibcode: 2014Sci...345...98L. doi:10.1126/science.1254312. PMC 4284148. PMID 24994655.

- ^ “Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death”. Toxicologic Pathology 35 (4): 495–516. (June 2007). doi:10.1080/01926230701320337. PMC 2117903. PMID 17562483.

- ^ “CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum”. Genes & Development 18 (24): 3066–77. (December 2004). doi:10.1101/gad.1250704. PMC 535917. PMID 15601821.

- ^ a b “Fusion of the EWS and CHOP genes in myxoid liposarcoma”. Oncogene 12 (3): 489–94. (February 1996). PMID 8637704.

- ^ “NADPH oxidase links endoplasmic reticulum stress, oxidative stress, and PKR activation to induce apoptosis”. The Journal of Cell Biology 191 (6): 1113–25. (December 2010). doi:10.1083/jcb.201006121. PMC 3002036. PMID 21135141.

- ^ a b “Targeting unfolded protein response in cancer and diabetes”. Endocrine-Related Cancer 22 (3): C1-4. (June 2015). doi:10.1530/ERC-15-0106. PMID 25792543.

- ^ a b “GRP78 Interacting Partner Bag5 Responds to ER Stress and Protects Cardiomyocytes From ER Stress-Induced Apoptosis”. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 117 (8): 1813–21. (August 2016). doi:10.1002/jcb.25481. PMC 4909508. PMID 26729625.

- ^ “Bcl-2 associated athanogene 5 (Bag5) is overexpressed in prostate cancer and inhibits ER-stress induced apoptosis”. BMC Cancer 13: 96. (March 2013). doi:10.1186/1471-2407-13-96. PMC 3598994. PMID 23448667.

- ^ “Analysis of ATF3, a transcription factor induced by physiological stresses and modulated by gadd153/Chop10”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 16 (3): 1157–68. (March 1996). doi:10.1128/MCB.16.3.1157. PMC 231098. PMID 8622660.

- ^ a b c “CHOP enhancement of gene transcription by interactions with Jun/Fos AP-1 complex proteins”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 19 (11): 7589–99. (November 1999). doi:10.1128/MCB.19.11.7589. PMC 84780. PMID 10523647.

- ^ “C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) up-regulates IL-6 transcription by trapping negative regulating NF-IL6 isoform”. FEBS Letters 541 (1–3): 33–9. (April 2003). doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00283-7. PMID 12706815.

- ^ “Physical and functional association between GADD153 and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta during cellular stress”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 271 (24): 14285–9. (June 1996). doi:10.1074/jbc.271.24.14285. PMID 8662954.

- ^ “CHOP transcription factor phosphorylation by casein kinase 2 inhibits transcriptional activation”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 278 (42): 40514–20. (October 2003). doi:10.1074/jbc.M306404200. PMID 12876286.

- ^ “Novel interaction between the transcription factor CHOP (GADD153) and the ribosomal protein FTE/S3a modulates erythropoiesis”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 275 (11): 7591–6. (March 2000). doi:10.1074/jbc.275.11.7591. PMID 10713066.

- ^ Song, Benbo; Scheuner, Donalyn; Ron, David; Pennathur, Subramaniam; Kaufman, Randal J. (October 2008). “Chop deletion reduces oxidative stress, improves beta cell function, and promotes cell survival in multiple mouse models of diabetes”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 118 (10): 3378–3389. doi:10.1172/JCI34587. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 2528909. PMID 18776938.

- ^ Maris, M.; Overbergh, L.; Gysemans, C.; Waget, A.; Cardozo, A. K.; Verdrengh, E.; Cunha, J. P. M.; Gotoh, T. et al. (April 2012). “Deletion of C/EBP homologous protein (Chop) in C57Bl/6 mice dissociates obesity from insulin resistance” (英語). Diabetologia 55 (4): 1167–1178. doi:10.1007/s00125-011-2427-7. ISSN 0012-186X. PMID 22237685.

- ^ a b Yong, Jing; Parekh, Vishal S.; Reilly, Shannon M.; Nayak, Jonamani; Chen, Zhouji; Lebeaupin, Cynthia; Jang, Insook; Zhang, Jiangwei et al. (2021-07-28). “Chop/Ddit3 depletion in β cells alleviates ER stress and corrects hepatic steatosis in mice”. Science Translational Medicine 13 (604). doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aba9796. ISSN 1946-6242. PMC 8557800. PMID 34321322.

- ^ WO application 2017192820, Monia, Brett P.; Thazha P. Prakash & Garth A. Kinberger et al., "GLP-1 receptor ligand moiety conjugated oligonucleotides and uses thereof", published 2017-11-09, assigned to Ionis Pharmaceuticals Inc. and AstraZeneca AB

- ^ Yong, Jing; Johnson, James D.; Arvan, Peter; Han, Jaeseok; Kaufman, Randal J. (August 2021). “Therapeutic opportunities for pancreatic β-cell ER stress in diabetes mellitus”. Nature Reviews. Endocrinology 17 (8): 455–467. doi:10.1038/s41574-021-00510-4. ISSN 1759-5037. PMC 8765009. PMID 34163039.

- ^ a b “Porcine Circovirus 2 Deploys PERK Pathway and GRP78 for Its Enhanced Replication in PK-15 Cells”. Viruses 8 (2): 56. (February 2016). doi:10.3390/v8020056. PMC 4776210. PMID 26907328.

- ^ “HIV Tat-Mediated Induction of Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cell Apoptosis Involves Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction”. Molecular Neurobiology 53 (1): 132–142. (January 2016). doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8991-3. PMC 4787264. PMID 25409632.

- ^ “HIV-1 gp120 induces type-1 programmed cell death through ER stress employing IRE1α, JNK and AP-1 pathway”. Scientific Reports 6: 18929. (January 2016). Bibcode: 2016NatSR...618929S. doi:10.1038/srep18929. PMC 4703964. PMID 26740125.

- ^ “Upregulation of CHOP/GADD153 during coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus infection modulates apoptosis by restricting activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway”. Journal of Virology 87 (14): 8124–34. (July 2013). doi:10.1128/JVI.00626-13. PMC 3700216. PMID 23678184.

- ^ “Endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway-mediated apoptosis in macrophages contributes to the survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis”. PLOS ONE 6 (12): e28531. (2011). Bibcode: 2011PLoSO...628531L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028531. PMC 3237454. PMID 22194844.

- ^ “Induction of ER stress in macrophages of tuberculosis granulomas”. PLOS ONE 5 (9): e12772. (September 2010). Bibcode: 2010PLoSO...512772S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012772. PMC 2939897. PMID 20856677.

- ^ “Endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to Helicobacter pylori VacA-induced apoptosis”. PLOS ONE 8 (12): e82322. (2013). Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...882322A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082322. PMC 3862672. PMID 24349255.

- ^ “Shiga toxin 1 induces apoptosis through the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in human monocytic cells”. Cellular Microbiology 10 (3): 770–80. (March 2008). doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01083.x. PMID 18005243.

- ^ “Shiga Toxins Induce Apoptosis and ER Stress in Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells”. Toxins 9 (10): 319. (October 2017). doi:10.3390/toxins9100319. PMC 5666366. PMID 29027919.

- ^ “Different induction of GRP78 and CHOP as a predictor of sensitivity to proteasome inhibitors in thyroid cancer cells”. Endocrinology 148 (7): 3258–70. (July 2007). doi:10.1210/en.2006-1564. PMID 17431003.

- ^ “C/EBP homologous protein inhibits tissue repair in response to gut injury and is inversely regulated with chronic inflammation”. Mucosal Immunology 7 (6): 1452–66. (November 2014). doi:10.1038/mi.2014.34. PMID 24850428.

- DDIT3のページへのリンク