ベンゾジアゼピン薬物乱用

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2023/11/13 07:48 UTC 版)

| ベンゾジアゼピン |

|---|

|

| ベンゾジアゼピン系の核となる骨格。 「R」の表記部分は、ベンゾジアゼピンの異なる 特性を付与する側鎖の共通部位である。 |

| ベンゾジアゼピン |

| ベンゾジアゼピンの一覧 |

| en:Benzodiazepine overdose |

| ベンゾジアゼピン依存症 |

| ベンゾジアゼピン薬物乱用 |

| ベンゾジアゼピン離脱症候群 |

| ベンゾジアゼピンの長期的影響 |

| ベンゾジアゼピン薬物乱用 | |

|---|---|

| 概要 | |

| 診療科 | 精神医学, 麻薬学[*], 中毒医学[*] |

| 分類および外部参照情報 | |

| ICD-10 | F13.1 |

| eMedicine | article/290585 |

| GeneReviews | |

世界保健機関による1996年の「ベンゾジアゼピンの合理的な利用」という報告書においては、ベンゾジアゼピン系の「合理的な利用」は30日までの短期間にすべきとしている[5]。

トリアゾラム、テマゼパム、アルプラゾラム、クロナゼパム、ロラゼパムらは、他のオキサゼパム、クロルジアゼポキシドと比較して身体的依存の可能性が高い。乱用の可能性(精神依存)は消失半減期・吸収率・薬物効果などにより違いがある[6][7]。

乱用率

薬物乱用においてベンゾジアゼピンが注目されることは少ない。しかしこれらは他の薬物らと共に頻繁に乱用されている(とりわけアルコール、覚醒剤、オピオイド)[12]。

ベンゾジアゼピンは様々な国々において乱用されており、その要素は地域的情勢・入手可能薬物によって様々である。たとえば英国とネパールではニトラゼパム乱用が一般的であるが[13][14]、米国ではそれが処方薬として入手不可能なため他のベンゾジアゼピンが乱用されている[7]。また英国とオーストラリアではテマゼパム乱用が見られ、特にジェルカプセルを溶かして注射され薬物関連死をまねいている[15][16][17]。このようなベンゾジアゼピンの水溶物を注射することは、大変危険であり深刻な健康被害をもたらす[18][19]。

ベンゾジアゼピンは一般的に乱用性薬物に分類されている。スウェーデンの研究では、ベンゾジアゼピンはスウェーデンにおいて最も乱処方されている薬物分類であった[21]。自動車運転者のベンゾジアゼピン服用については、これまでほとんど取り上げられることはなかったが、スウェーデンと北アイルランドの報告では、多くの場合に治療用投与量を超えているという[22][23]。ベンゾジアゼピン薬物乱用において警戒すべきサインは処方量の増加である。大部分を占める適正処方患者においては、処方量の増加に至ることはない[24]。

米国政府機関SAMHSAによる2004年の全米救急部への調査によれば、米国で最も乱用されている処方薬は催眠鎮静薬であり、薬物理由による救急部受診においては、催眠鎮静薬関係が35%を占め最多であった。その中はベンゾジアゼピンが多数(32%)であり、オピオイドによる救急部受診よりも多かった。また調査ではベンゾジアゼピン乱用率に男女差はなかった。薬物自殺においては、ベンゾジアゼピンは最も一般的に利用される薬物であり26%を占めていた。2004年の米国ではアルプラゾラムが最も乱用されるベンゾジアゼピンであり、続いてクロナゼパム・ロラゼパム・ジアゼパムらが4位までに入った[25]。2014年の医薬品と違法薬物を含めた過剰摂取による死亡者数において、4位がアルプラゾラムで4,217人(総数の9%を占める)、10位がジアゼパム1,729人である[26]。

危険因子

薬物乱用歴のある患者は、ベンゾジアゼピンの乱用リスクが大きいとされる[28]。

過去10年間を対象としたいくつかの研究において、家族にアルコール乱用歴ある場合や兄弟や子供がアルコール依存症である場合は、遺伝的健康者(genetically healthy persons)と比べて、男性の場合は高揚感が増大し、女性はその副作用により誇張反応となるとされている[29][30][31][32]。

すべてのベンゾジアゼピンは乱用リスクがあるが、特定カテゴリのベンゾジアゼピン薬は乱用リスクがさらに高い。たとえば短半減期かつ即効性の薬などは乱用リスクが高い[33]。

| この節の加筆が望まれています。 |

- ^ Tyrer, Peter; Silk, Kenneth R., eds (2008-01-24). “Treatment of sedative-hypnotic dependence”. Cambridge Textbook of Effective Treatments in Psychiatry (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 402. ISBN 978-0521842280

- ^ a b Griffiths RR, Johnson MW (2005). “Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds” (PDF). J Clin Psychiatry 66 Suppl 9: 31-41. PMID 16336040.

- ^ Sheehan MF, Sheehan DV, Torres A, Coppola A, Francis E (1991). “Snorting benzodiazepines”. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 17 (4): 457-68. doi:10.3109/00952999109001605. PMID 1684083.

- ^ Woolverton WL, Nader MA (December 1995). “Effects of several benzodiazepines, alone and in combination with flumazenil, in rhesus monkeys trained to discriminate pentobarbital from saline”. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 122 (3): 230-6. doi:10.1007/BF02246544. PMID 8748392.

- ^ *WHO Programme on Substance Abuse (1996年11月). Rational use of benzodiazepines - Document no.WHO/PSA/96.11 (pdf) (Report). World Health Organization. OCLC 67091696. 2013年3月10日閲覧。

- ^ Griffiths RR, Lamb RJ, Sannerud CA, Ator NA, Brady JV (1991). “Self-injection of barbiturates, benzodiazepines and other sedative-anxiolytics in baboons”. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 103 (2): 154-61. doi:10.1007/BF02244196. PMID 1674158.

- ^ a b Griffiths RR, Wolf B (August 1990). “Relative abuse liability of different benzodiazepines in drug abusers”. J Clin Psychopharmacol 10 (4): 237-43. doi:10.1097/00004714-199008000-00002. PMID 1981067.

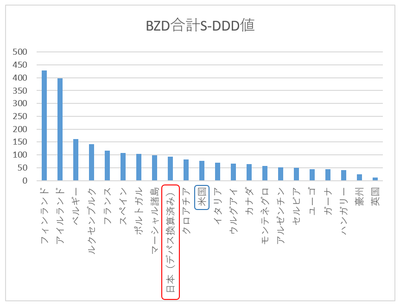

- ^ Psychotropic substances Statistics for 2011 (Report). 国際麻薬統制委員会. 2012. Part3 Table IV.2. ISBN 978-92-1-048153-3。

- ^ a b 戸田克広「ベンゾジアゼピンによる副作用と常用量依存」『臨床精神薬理』第16巻第6号、2013年6月10日、867-878頁。

- ^ a b c d AVAILABILITY OF INTERNATIONALLY CONTROLLED DRUGS (pdf). www.incb.org (Report). 国際麻薬統制委員会 en:INCB. 2015. 2016年6月8日閲覧。

- ^ 日本医師会、日本老年医学会『超高齢化社会におけるかかりつけ医のための適正処方の手引き』(pdf)日本医師会、2017年9月。

- ^ a b Karch, S. B. (2006). Drug Abuse Handbook (2nd ed.). USA: CRC Press. p. 572. ISBN 978-0-8493-1690-6

- ^ Chatterjee, A.; Uprety, L.; Chapagain, M.; Kafle, K. (1996). “Drug abuse in Nepal: a rapid assessment study”. Bulletin on Narcotics 48 (1–2): 11–33. PMID 9839033.

- ^ Garretty, D. J.; Wolff, K.; Hay, A. W.; Raistrick, D. (January 1997). “Benzodiazepine misuse by drug addicts”. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry 34 (Pt 1): 68–73. PMID 9022890.

- ^ Wilce, H. (June 2004). “Temazepam capsules: What was the problem?”. Australian Prescriber 27 (3): 58–59. オリジナルの2009年7月8日時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Ashton, H. (2002). “Benzodiazepine Abuse”. Drugs and Dependence. London & New York: Harwood Academic Publishers 2007年11月25日閲覧。

- ^ Hammersley, R.; Cassidy, M. T.; Oliver, J. (1995). “Drugs associated with drug-related deaths in Edinburgh and Glasgow, November 1990 to October 1992”. Addiction 90 (7): 959–965. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9079598.x. PMID 7663317.

- ^ Wang, E.C.; Chew, F. S. (2006). “MR Findings of Alprazolam Injection into the Femoral Artery with Microembolization and Rhabdomyolysis” (pdf). Radiology Case Reports 1 (3). オリジナルの2008年6月23日時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ “DB00404 (Alprazolam)”. Canada: DrugBank (2008年8月26日). 2014年5月1日閲覧。

- ^ Overdose Death Rates. By National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

- ^ Bergman, U.; Dahl-Puustinen, M. L. (1989). “Use of prescription forgeries in a drug abuse surveillance network”. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 36 (6): 621–623. doi:10.1007/BF00637747. PMID 2776820.

- ^ Jones, A. W.; Holmgren, A.; Kugelberg, F. C. (April 2007). “Concentrations of scheduled prescription drugs in blood of impaired drivers: considerations for interpreting the results”. Therapeutic Drug Monitor 29 (2): 248–260. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31803d3c04. PMID 17417081.

- ^ Cosbey, S. H. (December 1986). “Drugs and the impaired driver in Northern Ireland: an analytical survey”. Forensic Science International 32 (4): 245–58. doi:10.1016/0379-0738(86)90201-X. PMID 3804143.

- ^ Lader, M. H. (1999). “Limitations on the use of benzodiazepines in anxiety and insomnia: are they justified?”. European Neuropsychopharmacology: The Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology 9 (Suppl 6): S399–405. doi:10.1016/S0924-977X(99)00051-6. PMID 10622686.

- ^ “Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2004: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits”. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2004年). 2008年3月31日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年5月9日閲覧。

- ^ Warner M, Trinidad JP, Bastian BA, Minino AM, Hedegaard H (2016). “Drugs Most Frequently Involved in Drug Overdose Deaths: United States, 2010-2014” (pdf). Natl Vital Stat Rep (10): 1–15. PMID 27996932.

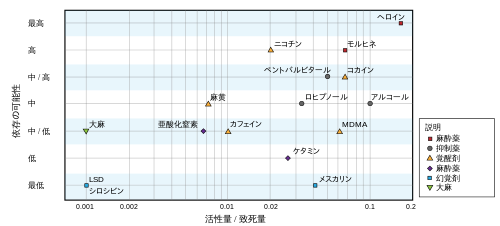

- ^ Robert S., Gable. “Acute Toxicity of Drugs Versus Regulatory Status”. In Jeffeson M. Fish. Drugs and society : U.S. public policy. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 149-162. ISBN 0-7425-4245-9

- ^ エフ・ホフマン・ラ・ロシュ. “Mogadon”. RxMed. 2009年5月26日閲覧。

- ^ Ciraulo, D. A.; Barnhill, J. G.; Greenblatt, D. J.; Shader, R. I.; Ciraulo, A. M.; Tarmey, M. F.; Molloy, M. A.; Foti, M. E. (Sep 1988). “Abuse liability and clinical pharmacokinetics of alprazolam in alcoholic men”. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 49 (9): 333–337. PMID 3417618.

- ^ Ciraulo, D. A.; Sarid-Segal, O.; Knapp, C.; Ciraulo, A. M.; Greenblatt, D. J.; Shader, R. I. (Jul 1996). “Liability to alprazolam abuse in daughters of alcoholics”. The American Journal of Psychiatry 153 (7): 956–958. PMID 8659624.

- ^ Evans, S. M.; Levin, F. R.; Fischman, M. W. (Jun 2000). “Increased sensitivity to alprazolam in females with a paternal history of alcoholism”. Psychopharmacology 150 (2): 150–162. doi:10.1007/s002130000421. PMID 10907668.

- ^ Streeter, C. C.; Ciraulo, D. A.; Harris, G. J.; Kaufman, M. J.; Lewis, R. F.; Knapp, C. M.; Ciraulo, A. M.; Maas, L. C. et al. (May 1998). “Functional magnetic resonance imaging of alprazolam-induced changes in humans with familial alcoholism”. Psychiatry Research 82 (2): 69–82. doi:10.1016/S0925-4927(98)00009-2. PMID 9754450.

- ^ Longo LP, Johnson B (April 2000). “Addiction: Part I. Benzodiazepines—side effects, abuse risk and alternatives”. Am Fam Physician 61 (7): 2121-8. PMID 10779253.

- ^ “Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse”. Lancet 369 (9566): 1047–53. (March 2007). doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831.

- ^ Dr Ray Baker. “Dr Ray Baker's Article on Addiction: Benzodiazepines in Particular”. 2009年2月14日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Professor C Heather Ashton (2002年). “BENZODIAZEPINE ABUSE”. Drugs and Dependence. Harwood Academic Publishers. 2007年9月25日閲覧。

- ^ a b 英国国立薬物乱用治療庁 2007, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b Gitlow, Stuart (2006-10-01). Substance Use Disorders: A Practical Guide (2nd ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. pp. 103-121. ISBN 978-0781769983

- ^ INCB: Psychotropic Substances - Technical Reports (Report 2016: Statistics for 2015) (PDF, 4.1MB)

- ^ Guidelines governing the prescription of benzodiazepines around the world benzo.org.uk

- ^ Shimane T, Matsumoto T, Wada K (October 2012). “Prevention of overlapping prescriptions of psychotropic drugs by community pharmacists”. 日本アルコール・薬物医学会雑誌 47 (5): 202–10. PMID 23393998.

- ^ “佐藤記者の「精神医療ルネサンス」抗不安・睡眠薬依存(8) マニュアル公開記念・アシュトン教授に聞いた”. 読売新聞. (2012年8月20日). オリジナルの2012年10月15日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ 世界保健機関 (1991). WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence - Twenty-seventh Report / WHO Technical Report Series 808 (pdf) (Report). World Health Organization. pp. 4-6、12. ISBN 92-4-120808-2。

- ^ Psychotropic substances Statistics for 2011 (Report). 国際麻薬統制委員会. 2012. Part3 Table IV.2 - 3. ISBN 978-92-1-048153-3。

- ^ “向精神薬多剤投与に関する届出及び状況報告について”. 厚生労働省 近畿厚生局 (2014年7月24日). 2014年7月24日閲覧。

- ^ 橋本佳子 (2018年2月8日). “抗不安薬・睡眠薬、「12カ月以上」で減点”. m3.com. 2018年3月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Health and Drug Education - Oral Sleeping Medicines”. 香港政府衛生署薬物局. 2014年1月12日閲覧。

- ^ Guidelines for Benzodiazepine Using in Sedation and Hypnosis (Report). 衛生福利部食品薬物管理署. 13 October 1996. 0960510417。 - 中国語 苯二氮平類(Benzodiazepines)藥品用於鎮靜安眠之使用指引

- ^ “Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2006: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits”. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2006年). 2009年1月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2009年2月9日閲覧。

- ^ American Geriatrics Society. Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question (Report). ABIM Foundation. 2014年2月2日閲覧。

- ^ Drug Utilization Review of Benzodiazepine Use in First Nations and Inuit Populations (Report). カナダ保健省. 2005年9月. 2013年1月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。

- ^ "Summary". Prescribing drugs of dependence in general practice, Part B Benzodiazepines (Report). 王立オーストラリア総合医学会. July 2015.

- ^ “Clinical topics - Benzodiazepines, when to prescribe”. 南オーストラリア州保健局. 2014年1月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Mental Health and Drug & Alcohol- Factsheets - Benzodiazepines”. ニューサウスウェールズ州保健局. 2014年2月20日閲覧。

- ^ "Hypnotics and anxiolytics - a wake-up call" (Press release). ニュージーランド保健省 Medsafe. 12 June 2010.

- ^ Report of the Benzodiazepine Committee (PDF) (Report). Department of Health and Children, Ireland. October 2002. p. 57.

- ^ “Conditions & Treatments - Anxiety”. アイルランド保健サービス. 2014年1月13日閲覧。

- ^ “Conditions & Treatments - Phobias”. アイルランド保健サービス. 2014年1月13日閲覧。

- ^ “Conditions & Treatments - Insomnia”. アイルランド保健サービス. 2014年1月13日閲覧。

- ^ A consensus statement on the use of Benzodiazepines in specialist mental health services (Report). College of Psychiatry of Ireland. April 2012.

- ^ “College releases guidelines on benzodiazepines”. Irish Medical Times. (2012年11月28日)

- ^ Committee on Safety of Medicines (January 1988). BENZODIAZEPINES, DEPENDENCE AND WITHDRAWAL SYMPTOMS (Report) (1988; Number 21: 1-2 ed.).

- ^ NHS Graham (October 2008). GUIDANCE FOR PRESCRIBING AND WITHDRAWAL OF BENZODIAZEPINES & HYPNOTICS IN GENERAL PRACTICE (PDF) (Report). p. 1. 2008年10月1日時点のオリジナル (PDF)よりアーカイブ。

- ^ BRITISH NATIONAL FORMULARY (Report). MHRA. November 2013. 4.1 HYPNOTICS AND ANXIOLYTICS.

- ^ スコットランド政府 (2008年6月3日). “Statistical Bulletin - DRUG SEIZURES BY SCOTTISH POLICE FORCES, 2005/2006 AND 2006/2007” (PDF). Crime and justice series. Scotland: scotland.gov.uk. 2009年2月13日閲覧。

- ^ Northern Ireland Government (2008年10月). “Statistics from the Northern Ireland Drug Misuse Database: 1 April 2007 - 31 March 2008” (PDF). Northern Ireland: Department of Health and Social Services and Public Safety. 2009年8月26日閲覧。

- ^ “Farmacotherapeutisch Kompas - Benzodiazepinen”. オランダ厚生省社会保険局. 2014年1月12日閲覧。

- ^ 国際麻薬統制委員会 (January 1999). Operation of the international drug control system (PDF) (Report). 2008年11月17日時点のオリジナル (PDF)よりアーカイブ。2009年2月13日閲覧。

- ^ “Läkemedelsbehandling vid ångest (Drug therapy for anxiety)”. スウェーデン医療製品庁. 2011年12月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Behandling av sömnsvårigheter”. スウェーデン医療製品庁. 2014年1月12日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Indenrigs- og Sundhedsministeriet [in 英語] (9 July 2008). Vejledning om ordination af afhængighedsskabende lægemidler (Report). Chapt.4. VEJ nr 38 af 18/06/2008 Historisk。

- ^ "Pas på benzodiazepiner (ベンゾジアゼピンへの注意喚起)" (Press release). デンマーク国家保健委員会( Sundhedsstyrelsen præciserer). 24 June 2008. 2014年7月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。

- ^ a b c Vejledning om ordination af afhængighedsskabende lægemidler (依存性薬物の処方ガイドライン) (PDF) (Report). デンマーク国家保健委員会. April 2008. Chapt.4.

- ^ “Le bon usage des benzodiazépines par les patients”. 厚生省 (フランス). 2014年1月13日閲覧。

- ^ "Sleep disorders: fight against reflex "sleeping pills"" (Press release). フランス高等保健機構. 11 August 2012.

- ^ Modalités d'arrêt des benzodiazépines et médicaments apparentés chez le patient âgé (Report). フランス高等保健機構. August 2007.

- ^ “Lääkeriippuvuuden ehkäisy ja hoito”. フィンランド国立保健福祉研究機構. 2013年1月20日閲覧。

- ^ VANEDANNENDE LEGEMIDLER FORSKRIVNING OG FORSVARLIGHET (PDF) (Report). ノルウェー保健監査委員会. 14 September 2001. IK-2755。

- ^ “Guidelines for the Prescription of Benzodiazepines in Norway”. Benzo.org.uk. 2014年5月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Fakta om de enkelte rusmidlene - Fakta om benzodiazepiner”. ノルウェー公衆衛生機構 (2013年11月29日). 2013年12月20日閲覧。

- 1 ベンゾジアゼピン薬物乱用とは

- 2 ベンゾジアゼピン薬物乱用の概要

- 3 依存と離脱症状

- 4 各国の状況

- 5 参考文献

- ベンゾジアゼピン薬物乱用のページへのリンク