ワンガヌイ

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2022/10/10 04:36 UTC 版)

歴史

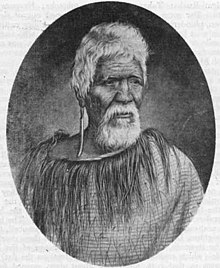

マオリ族の入植

ワンガヌイ川の河口周辺地域は、ヨーロッパ人の到着より前のマオリ族の入植において主要拠点であった。プティキ(プティキファラヌイの略)という名称のパーは、現在に至るまでテ・アティ・ハウヌイアパパランギというイウィのンガティ・トゥポホというハプの故郷であり[25]、伝説の探検家タマテア・ポカイ・フェヌアが髪飾り(プティキ)を結ぶための亜麻を探すため沿岸に召使いを送ったことから、この名称で呼ばれるようになった[26]。

1820年代、この地域の沿岸の部族がンガティ・トアの首長テ・ラウパラハが治めるカピティ島の本拠地を攻撃した。テ・ラウパラハは1830年に報復し、プティキを破壊して住民を虐殺した[27]。

ヨーロッパ人の入植

1831年、初めてヨーロッパ人の貿易商が到着した。1840年にはキリスト教伝道師オクタヴィアス・ハドフィールドとヘンリー・ウィリアムズが到着し、ワイタンギ条約への署名を集めた[27]。1840年6月20日、ジョン・メイソンとメイソン夫人、リチャード・マシューズ(平信徒の伝道者)と妻ジョハンナが到着し、英国聖公会宣教協会(CMS)の伝道拠点を設立した[28]。1843年にはリチャード・テイラーが伝道拠点に加わった[29]。1843年1月5日、メイソンはトゥラキナ川を横断中に溺死した[29][30]。メイソンが建てたレンガ造りの教会は信徒のニーズには不十分となっていた上、地震で損傷していたため、1844年までにテイラーの指導の下で新たな教会が建築され、川の各パーからキリスト教信者の規模と人数に比例して材木が提供された[31]。

ニュージーランド会社は、ウェリントンに落ち着くと、他の入植に適した場所を探した。1840年、エドワード・ギボン・ウェイクフィールドの弟ウィリアム・ウェイクフィールドが40,000エーカーの土地の売却を取り決め、河口から4キロメートルの場所に、ニュージーランド会社の役員の1人であったピーター卿に因んだ「ピーター」という名前の町を設立した[27]。1846年、入植地はワンガヌイ川の川上のイウィの首長テ・ママクによって脅かされた。町の防衛のため、1846年12月13日に英国軍が到着し、入植者を守るためにラットランドとヨークの2つの陣地が建設された。1847年5月19日と7月19日に小規模な衝突があり、膠着状態の末、川上のイウィは住まいに戻った[32]。1850年までに、テ・ママクはテイラーからキリスト教の教えを受けた[32]。1847年には、ギルフィラン一家4人が殺害され、家が略奪される事件が起こった[33]。

1854年1月20日、市の名称が正式にワンガヌイに変更されたが、新たな市は初期から問題を抱えていた。地元部族からの土地購入が無計画かつイレギュラーであったため、多くのマオリが未だ権利を主張する土地へのパケハ(ヨーロッパ系住民)の流入に腹を立てていた。町の設立から8年後、植民地住民と地元部族の間でようやく合意に達したが、一部禍根が残った(現在に至るまで残っている)。

この時代の後、ワンガヌイは急速に発展し、土地は開墾され牧草地となった。1860年代のニュージーランド戦争時、町は主要軍事拠点となったが、テ・ケエパ・テ・ランギヒウィヌイ率いるプティキの地元マオリは、入植者に対して友好的な立場を維持した。1871年、町に橋が建設され[34]、6年後にはアラモホに鉄道橋も建設された[27]。1886年までに、ニュープリマス・ウェリントンの双方と鉄道で接続された。1872年2月1日、町はバラとして組織され、ウィリアム・ホッグ・ワットが初代首長に就任した。その後、1924年7月1日に市として宣言された[27]。

ワンガヌイ女性政治同盟

1893年、ニュージーランド女性キリスト教禁酒連合のワンガヌイ支部の代替として、マーガレット・ブロックが女性活動家のクラブ、ワンガヌイ女性参政権同盟(Wanganui Women's Franchise League)を設立し、元首相ジョン・バランスの後妻エレン・バランスがイングランドへ発つまで初代会長を務めた。その後、ブロックが会長に就任し、女性参政権を獲得すると、組織の名称を女性政治同盟(Women's Political League)に変更した。加盟者数は最大で約3,000人に上った。月例会議では男女同権主義に関する学術的な質問に重点的に取り組み、エレン・バランスは夫の蔵書をクラブに寄贈した。ブロックとジェシー・ウィリアムソンがニュージーランド女性国民評議会との関係を取り持った。ブロックが死去し、ウィリアムソンがクライストチャーチに移住した1903年までに、クラブの活動は低下し、蔵書は地元の公共図書館に寄贈された[35]。

20世紀

1920年、おそらくワンガヌイ最大のスキャンダルとなる、チャールズ・マッケイ市長が自身の同性愛に関して脅迫した青年詩人ダーシー・クレスウェルに発砲・負傷させる事件が発生した。マッケイは7年服役し、町の市民記念碑から名前が消されたが、クレスウェル(自身も同性愛者)は「健全な精神を持つ若者」として称賛された[36]。1895年、マッケイの名前がサージェント美術館の礎石に戻された[37]。

ワンガヌイ川の流域は、マオリにとって聖域とみなされており、ワンガヌイ地域は現在でも土地所有権をめぐる反感の中心とみなされている。1995年には、モウトア・ガーデン(地元マオリにはパカイトレと呼ばれている)が、ワンガヌイのイウィによる土地所有権をめぐる主に平和的な抗議活動によって、79日間占拠された[9]。

ワンガヌイは、1976年から1995年まで、ニュージーランド警察の国家警察システムの拠点であった。初期のスペリー社によるメインフレームベースの機密情報・データ管理システムで、「ワンガヌイ・コンピューター」の通称で知られていた。このシステムを収容する建物は、1982年11月18日に発生したニュージーランド最大の自爆事件で、ゼリグナイト爆弾による爆撃の標的となった。

- ^ https://www.whanganui.govt.nz/Your-Council/About-Whanganui-District-Council/Our-History#section-2 Whanganui District Council, 'Our Coat of Arms'

- ^ a b Subnational population estimates (RC, SA2), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996-2021 (2021 boundaries), Subnational population estimates (TA, SA2), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996-2021 (2021 boundaries), Subnational population estimates (urban rural), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996-2021 (2021 boundaries), Statistics New Zealand

- ^ “Notice of the Determination of the Minister for Land Information on Assigning Alternative Geographic Names”. Land Information New Zealand (2012年12月13日). 2013年3月16日閲覧。

- ^ “Residents free to choose city's spelling”. TVNZ. 2015年1月19日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Whanganui or Wanganui – it's up to you”. The New Zealand Herald. (2009年12月18日)

- ^ a b “'H' to be added to Wanganui District name”. Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) (2015年11月17日). 2016年2月2日閲覧。

- ^ “Whanganui in 1841”. New Zealand History. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 2020年10月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年10月29日閲覧。

- ^ “The Wanganui/Whanganui Debate: A Linguist's View Of Correctness”. Victoria University of Wellington. pp. 11–12 (2010年). 2020年10月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年7月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Moutoa Gardens protest”. 2020年10月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年10月29日閲覧。

- ^ “How we say 'Whanganui'”. 2020年10月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年10月29日閲覧。

- ^ “Frequently Asked Questions about the Minister's Decision”. 2020年10月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年10月29日閲覧。

- ^ a b Burns, Kelly (2009年4月4日). “Wanganui spelling change slammed”. Stuff. 2020年10月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2015年1月19日閲覧。

- ^ “Board to decide Wanganui spelling”. Otago Daily Times (Allied Press). (2009年3月25日). オリジナルの2020年10月29日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2020年10月29日閲覧。

- ^ “Michael Laws condemns 'petty vandals' for adding h to Wanganui”. Newshub (MediaWorks TV). (2009年3月3日). オリジナルの2020年10月29日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2020年10月29日閲覧。

- ^ New Zealand Geographic Board to publicly consult on ‘h’ in Wanganui. 30 March 2009. Archived 25 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Whanganui. Archived 23 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b “Whanganui decision 'great day for city' – Turia”. The New Zealand Herald. (2009年9月17日). オリジナルの2012年10月12日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2009年9月17日閲覧。

- ^ “Results of Referendum 09” (2009年5月21日). 2010年5月25日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2009年5月22日閲覧。

- ^ a b Emerson, Anne-Marie. “Wanganui says: No H”. Wanganui Chronicle (NZME Publishing). オリジナルの2020年10月29日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2020年10月29日閲覧。

- ^ “The Wanganui/Whanganui Debate: A Linguist's View Of Correctness”. Victoria University of Wellington. p. 17 (2010年). 2022年9月6日閲覧。

- ^ “Wanganui proposed change to Whanganui”. Land Information New Zealand. 2020年10月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2020年10月29日閲覧。

- ^ “Whanganui or Wanganui - it's up to you” (英語). NZ Herald 2021年11月30日閲覧。

- ^ “Notice of the Final Determination of the Minister for Land Information on a Local Authority District Name”. 2021年10月15日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年10月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Seal of approval for spelling of Manawatū-Whanganui region” (英語). RNZ. (2020年1月2日). オリジナルの2020年10月29日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “Pūtiki Pā”. Māori Maps. 2015年12月3日閲覧。

- ^ Young, David (2015年8月24日). “Whanganui tribes”. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 2015年12月3日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e Wises New Zealand Guide, 7th Edition, 1979. p. 494.

- ^ “Pre 1839 Settlers in New Zealand”. 2016年4月8日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2022年9月6日閲覧。

- ^ a b Rogers, Lawrence M. (1973). Te Wiremu: A Biography of Henry Williams. Pegasus Press

- ^ “The Church Missionary Gleaner, July 1843”. Progress of the Gospel in the Western District of New Zealand – the death of Rev J Mason. Adam Matthew Digital. 2015年10月12日閲覧。

- ^ “The Church Missionary Gleaner, June 1845”. Erection of Places of Worship in New Zealand. Adam Matthew Digital. 2015年10月13日閲覧。

- ^ a b “The Church Missionary Gleaner, December 1850”. The Chief Mamaku. Adam Matthew Digital. 2015年10月17日閲覧。

- ^ “The Church Missionary Gleaner, January 1854”. The Murderer Rangiirihau. Adam Matthew Digital. 2015年10月18日閲覧。

- ^ “THE GOVERNOR'S VISIT TO WANGANUI. NEW ZEALAND MAIL”. paperspast.natlib.govt.nz (1871年12月9日). 2020年9月5日閲覧。

- ^ Labrum, Bronwyn (1993). “Wanganui Women's Political League 1893-c.1902”. In Else, Anne. Women Together: A History of Women's Organisations in New Zealand. Wellington, NZ: Historical Branch, Dept. of Internal Affairs; Daphne Brasell Assoc. Press. pp. 77–78

- ^ “Charles Mackay and D'Arcy Cresswell”. 2007年10月10日閲覧。

- ^ “Wanganui mayor shoots poet”. 2011年4月17日閲覧。

- ^ “Cycle bridge opens in time for summer” (英語). www.whanganui.govt.nz. 2022年7月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Climate Data”. NIWA. 2007年11月2日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Age and sex by ethnic group (grouped total response), for census usually resident population counts, 2006, 2013, and 2018 Censuses (urban rural areas)”. nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz. 2020年9月13日閲覧。

- ^ “Whanganui’s Climate Change Action Wins 2022 Smart21 Communities Listing”. Climate Adaptation Platform. 2022年9月7日閲覧。

- ^ “Boat Building Business Booms”. Wanganui Chronicle. 2015年4月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Building better boats”. Crown Fibre Holdings. 2015年4月1日閲覧。

- ^ Maslin, John. “Pride of Wanganui heads to open water for first sea trial”. New Zealand Herald. APN 2015年4月1日閲覧。

- ^ “At the Helm – Q-West's success story”. m.nzherald.co.nz. 2015年11月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Helmet designed in Wanganui wins elite award”. m.nzherald.co.nz. 2015年11月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Death of Mr F. Whitlock”. Wanganui Chronicle L (12145): p. 5. (1908年8月24日) 2014年1月12日閲覧。

- ^ “New pear varieties going down a treat”. The New Zealand Herald. 2019年4月11日閲覧。

- ^ Stowell, Laurel (2016年5月18日). “Disease ends orchard and jobs”. Wanganui Chronicle 2020年1月17日閲覧。

- ^ “Innovative bill protects Whanganui River with legal personhood” (英語). www.parliament.nz (2017年3月28日). 2022年9月3日閲覧。

- ^ “ELECTION RESULTS – WHANGANUI”. Wanganui Chronicle. (2016年10月8日) 2016年10月9日閲覧。

- ^ “Art gallery has one week to find $3.3m”. RNZ (2016年6月23日). 2016年9月24日閲覧。

- ^ “Explore the Collection”. Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua Whanganui. 2020年1月17日閲覧。

- ^ “Sarjeant Gallery”. Heritage New Zealand. 2022年9月6日閲覧。

- ^ “War Memorial Hall”. Whanganui District Library. Whanganui District Council. 2016年2月1日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年4月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Rotokawau Virginia Lake” (英語). www.whanganui.govt.nz. 2022年3月10日閲覧。

- ^ “International Exchange”. List of Affiliation Partners within Prefectures. Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR). 2015年11月21日閲覧。

- ^ Wood, Simon (2009年2月26日). “Laws questions value of sister city relationship”. Wanganui Chronicle. オリジナルの2011年7月16日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ワンガヌイのページへのリンク