Steven Spielberg vs. Netflix

The director is again challenging the streaming giant’s ability to compete for Oscars—and he has a point, even if he doesn’t have much industry support.

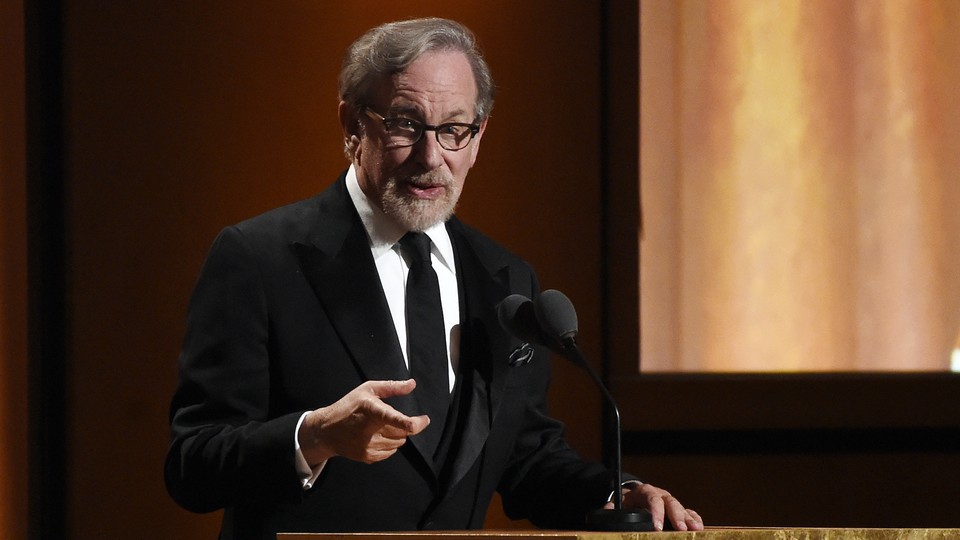

At 72 years old, Steven Spielberg has made movies for several decades and has an estimated net worth of $3.7 billion. He might be one of Hollywood’s most beloved directors, but it’s not too difficult for the industry’s newer generation to view him as someone who might be a little out of touch with the ordinary movie consumer’s experience. So when the Oscar-winning filmmaker first publicly aired complaints about Netflix’s release strategy last March—contending that films debuting on the streaming service concurrent with a very limited theatrical release shouldn’t be eligible for Oscars—he was mostly ignored or dismissed.

In the year that followed, Netflix began a drawn-out, still-unresolved battle with the Cannes Film Festival over the eligibility of its movies. The company then spent an unprecedented amount of money on an awards campaign for Roma that netted the film three Oscars (though it missed on Best Picture). After that show of force, Spielberg has responded in kind; he is preparing to petition the Academy to ban Netflix movies from Oscar contention unless they have an exclusive theatrical “window” of four weeks. It’s a bid that, judging by comments from many Oscar voters, probably won’t attract the necessary support (the next Academy meeting, where such an issue could be raised, is in April). But Spielberg’s demand shouldn’t be written off as being hostile to change, though many people in the industry are suggesting exactly that. It’s more of a last-ditch effort at compromise with a company that’s rapidly changing the way people think of cinema.

Currently, Oscar rules demand that a film have a one-week theatrical engagement in Los Angeles during the calendar year to be eligible for awards. That’s more than enough for Netflix, which usually releases its movies simultaneously online and in a few indie theaters to qualify. Major theater chains refuse to screen Netflix movies because of that “day-and-date” strategy; the agreed-upon window of exclusivity for multiplexes is 90 days, after which films can be made available online. Last year, Netflix showed some willingness to budge from its hard-and-fast rule that movies be made available to subscribers instantaneously. Roma was exclusively in theaters for three weeks before dropping on Netflix, while The Ballad of Buster Scruggs and Bird Box also received limited, exclusive runs in cinemas.

Those moves were partly a concession to Oscar voters, and partly an acknowledgment that Roma (which is designed to be projected with sophisticated Dolby Atmos speakers) offered a unique in-theater experience that some film fans might seek out. It was also an indication to major directors who might want to work with Netflix that the company was not opposed to cinemas. According to The Hollywood Reporter, Netflix has been planning similar theater runs for its big 2019 awards contenders, which include Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman, Steven Soderbergh’s The Laundromat, David Michôd’s The King, Dee Rees’s The Last Thing He Wanted, Noah Baumbach’s as-yet-untitled new film, and Fernando Meirelles’s The Pope.

Those planned (short) theatrical runs are apparently not enough for Spielberg. Last year, when promoting his film Ready Player One, he mused that Netflix movies should be treated as TV releases and be eligible for Emmys instead of Oscars. “I don’t believe that films that are just given token qualifications in a couple of theaters for less than a week should qualify for the Academy Award nomination,” the director said. As an Academy governor from the director’s branch, Spielberg is using his celebrity and clout to speak for a group of members who are alarmed that the theatrical experience will soon go extinct. “I’m a firm believer that movie theaters need to be around forever,” he said in an awards speech a week before the 2019 Oscars.

Among Netflix’s disruptive qualities is its lack of transparency—even when its films play in theaters, their box-office totals aren’t reported, because the company rents, or “four-walls,” the screen from the cinema and pockets whatever ticket sales it gets. In general, box-office totals are independently reported and evaluated. Netflix’s audience numbers are a proprietary secret, and the company only announces very limited viewership data for its biggest hits. Though Hollywood’s obsession with box office can be one-dimensional, the evidence of a high-grossing hit is a crucial metric for movie studios. A film like Black Panther grossing $700 million domestically, for instance, can help sway producers into backing more diverse projects in the future.

The biggest fear for directors like Spielberg, though, is that Netflix’s current torrent of content will prove unsustainable—no major studio pumps out movies at that pace and quantity—and that whatever changes it forces on the industry will be difficult to undo. As the at-home, online viewing experience becomes more of a cultural norm, paying to go to a theater could become a boutique experience, which is anathema to many generations who were raised on cinema. By leveraging the Oscars’ rules, Spielberg is taking advantage of something he knows Netflix cares about (given its massive “for your consideration” marketing budgets during awards season) and trying to propose the trade-off of a 28-day theatrical window.

The idea will likely fail. Netflix responded vociferously to the reports, saying in a statement, “We love cinema. Here are some things we also love: Access for people who can’t always afford, or live in towns without, theaters. Letting everyone, everywhere enjoy releases at the same time. Giving filmmakers more ways to share art. These things are not mutually exclusive.” Industry soundings on Spielberg’s proposal have been widely negative, with some Academy members saying that when it comes to streaming, the “ship has sailed.” Netflix works with a lot of high-profile filmmakers (some of whom, like Ava DuVernay, tweeted in support of the company). It also makes a lot of the mid-budget movies that major studios largely ignore these days—a budget range that’s essential for voting bodies like the Academy because it produces the kinds of prestige dramas that tend to win awards.

The argument that Netflix caters to people who lack access to theaters is a little simplistic. With a 28-day window, everyone in the U.S. would still be able to see the same movies within weeks, theater or not; Roma’s three-week cinema exclusivity hardly caused a stir last December. Plus, Netflix is a private company, not a public utility. It’s a business that provides a service specifically to subscribers who have high-speed internet and who can afford a monthly subscription—not “everyone, everywhere.” Still, the company’s cultural reach can’t be overstated, and while its archival cinematic offerings are extremely thin, its library is filled with worthwhile projects from the past few years and is only expanding as the months go on.

For all those reasons, Spielberg’s plan will probably not get the required votes to change Academy rules this year. The real junction point for Netflix will come later in 2019, as it gears up for the biggest movie release in the company’s lifetime: The Irishman, a gangster epic starring Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, and Joe Pesci. Demand by viewers to see that film in theaters might be high enough to reopen discussions between the company and big theater chains on how to get a Netflix movie into AMCs, Regals, and other multiplexes. If that moment passes without a resolution, Spielberg’s fears about the decline of the old-fashioned moviegoing experience could be realized.