EDITOR’S NOTE: With pro wrestling/sports entertainment playing to empty arenas, anxiously awaiting a green light to reconnect with a live audience, it’s an ideal time to take a look back at some of some of the greats of yesteryear who helped paved the way for those who followed.

He was the diamond ring and Cadillac man — “two hundred and thirty-five pounds of twisted steel and sex appeal with the heavenly body that women love but men fear.”

Long before “Stone Cold” Steve Austin became a national symbol for the anti-establishment movement, there was Sputnik Monroe, a salty-tongued, anti-authoritarian rebel who sported a trademark white streak down the middle of his hair along with a wild streak in the ring and a cocksure strut that just dared you to get in his way.

Monroe, who died on Nov. 3, 2006, at the age of 78 following a long battle with respiratory illness, was a character the likes of which professional wrestling will never see again.

“Sputnik was a force. He was a guy who made a difference. There just was never anyone exactly like him,” said the late Lance Russell, the voice of Memphis wrestling for half a century. “There’s the Jerry Lawlers, the Jackie Fargos, the Ric Flairs, and all these guys who are great in their own right, but Sputnik Monroe was an absolute one-of-a-kind-character.”

“It’s the end of an era, but Sputnik was a man who would want to be remembered the way he lived, full of fun and one who believed in rights for everyone,” added longtime Memphis wrestling announcer Corey Maclin.

Monroe was one of the most colorful and controversial personalities in the supercharged world of professional wrestling. But his legacy transcends the wrestling ring.

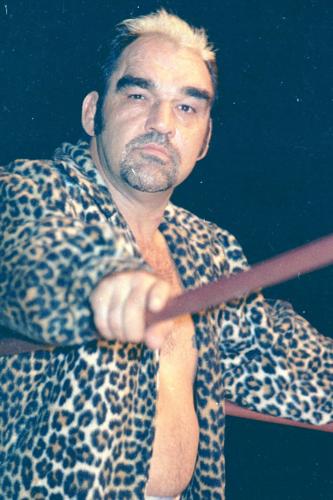

Sputnik Monroe fought to end segregation in Memphis. Provided/Chris Swisher Collection

A hero to fans black and white, Monroe will be forever remembered as a cultural icon who challenged and successfully broke down the color barrier in pro wrestling and helped exact change in the establishment.

Monroe’s tremendous influence was given an entire chapter in cultural historian Robert Gordon’s “It Came From Memphis,” a book which looks at the town’s rich musical heritage that nurtured Elvis Presley and the Stax soul sound, as well as its eccentric, larger-than-life characters like Monroe, who insisted on integrated crowds at his wrestling matches, laying the groundwork for rock shows to do the same.

Monroe captured the imagination of that segregated Southern town’s avid wrestling following in the late 1950s, building a strong rapport with Black fans who were forced to sit in the nosebleed section of the old Ellis Auditorium, a section derisively referred to as the “crow’s nest.” He cultivated friendships within the town’s Black community, and even though he worked as a heel in the ring, he became a champion for their cause.

Initially loathed by White audiences for his arrogant persona and detested outside the ring for his friendship with Blacks, Monroe would merely turn to the small Black audience in the building’s segregated upper rafters, raise his fist in defiance and acknowledge thunderous cheers from those in the balcony who celebrated every performance of the one wrestler who treated them with respect and friendship.

“Sputnik wouldn’t even look at the White people who were booing him when he came into the ring,” longtime Memphis deejay and television personality Johnny Dark told the Memphis Commercial Appeal. “Then all of a sudden out of nowhere he’d look up and raise both arms in the air to the balcony. And every single Black person in the balcony would stand up and raise their hands and cheer him.”

And, not unlike another Memphis favorite, Elvis Presley, Monroe would become a hero to the rock-and-roll-loving White youth who related to his rebellious nature. His connection to African-Americans also was genuine.

“There was a group of wealthy White kids that dug me because I was a rebel,” Sputnik once said. “I’m saying what they wanted to say, only they were just too young or inexperienced or afraid to say it. You have a Black maid raising your kids and she’s talking about me all of the time, so I may not be in the front living room, but I’m going in the back door of your house, feeding your kids on Monday morning and sending them to school. And meeting the bus when they come home. Pretty powerful thing.”

Monroe, one of the town’s top drawing cards, eventually was able to appeal to the promoters’ sense of greed, convincing the local matchmakers that they were missing out on tremendous earnings by confining Black patrons to the smaller “Blacks only” section of the balcony. Finally, overlooking black and white in favor of the color green, promoters integrated seating and saw their profits climb.

“There used to be a couple of thousand Blacks outside wanting in. So I would tell management I’d be cutting out if they don’t let my Black friends in,” explained Monroe. “I had the power because I’m selling out the place, the first guy that ever did, and they damn sure wanted the revenue.”

Once wrestling’s mixed audience became part of the status quo, the Memphis music scene followed and nightclubs became integrated.

Born to be wild

He was born Rocco Monroe DiGrazio on Dec. 18, 1928, in Dodge City, Kan. His father had been killed in an airplane crash shortly before his birth, and his formative years were spent living with his grandparents. His mother remarried, and at 17 years old, he became Rock Monroe Brumbaugh, taking the name of his stepfather.

He started his wrestling career in 1945. Monroe, wearing pink shoes and sequined robes, adopted the ring moniker Pretty Boy Rocque and spent his first several years working shows on the traveling carnival circuit where he would pick fights with local tough guys to sell more tickets. He claimed to have never been beaten in a “shoot” match during the five years he spent working the carnivals.

Monroe spent a few more years wrestling locals in small towns, but eventually moved to bigger shows and bigger markets and changed his name to Elvis Rock Monroe when a promoter in Louisville thought he looked like Elvis Presley.

Sputnik Monroe was an unlikely civil rights icon. Provided/Chris Swisher Collection

“It sounded like rock and roll,” Monroe once said. “I would carry a guitar into the ring. I think I could play one chord and then get the hell beat out of me with my own guitar.”

Monroe got the Cold War-era nickname after he gave a Black hitchhiker a ride to the arena one day. A fan saw Sputnik walking with his arm around his Black friend and became irate when Sputnik pretended to kiss him on the lips. The racist fan made such a fuss that security threatened to throw her out if she didn’t settle down and stop hurling obscenities.

Attempting to tone down her string of racial epithets, she screamed, “You’re nothing but a damned Sputnik,” a reference to the satellite the hated communist Russians had just launched into space. The name stuck with the wrestler the rest of his career.

Monroe was a master showman who walked the walk and talked the talk, combining mat ability with mic skills, but it was his electric personality that propelled him to the top.

“Win if you can, lose if you must, always cheat, and if they take you out, leave tearing down the ring,” Sputnik described his life philosophy.

Dubbed “The Sweet Man,” Monroe had bushy eyebrows, a whiskey voice that gave his promos a sharp edge and an impeccable sense of crowd psychology. And, like other originals from his era, he lived his gimmick.

Married six times, Sputnik carried a case of Scotch in the trunk of his Cadillac, driving from town to town in a life of one-night stands and baloney blowouts. He spawned a number of Sputnik look-alikes including a pair of Rocket Monroes (Bill Fletcher and Maury High), Flash Monroe (Gene Sanizzaro) and Jet Monroe (Sputnik’s real-life brother Gary Brumbaugh).

Skirmishes with police weren’t an unusual occurrence for Monroe, who liked to hang out around Beale Street, then the hub of the Black community in Memphis, which made him a target of police who would charge him with violating the local vagrancy law. City leaders frowned at a popular local figure like Monroe spending his time socializing in Black clubs on Beale Street.

“I got arrested once for vagrancy for hanging out on Beale Street,” he said. “I got a colored lawyer and went to court. I told them this was the United States of America, and I could go wherever I damned well pleased. They fined me $25, but after about a half-dozen arrests, they gave up.”

But he loved the Beale Street lifestyle, and soon became a favorite of Black wrestling fans at the Monday night wrestling shows at Ellis Auditorium, the site where Monroe made his strongest statements.

Years later he would be publicly honored with a display at Memphis’ Rock ‘N Soul Museum, located on that same street, for his role in the integration of public events. Along with exhibits of Elvis, B.B. King and Otis Redding, another display features a gold wrestling jacket, flowered trunks and wrestling shoes, with a plaque that reads, “Sputnik Monroe played a major part in destroying the color lines in Memphis.”

Monroe also enjoyed hanging out at the legendary Sun Records studio with Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis and other Memphis-based recording greats. His musical influence would be felt nearly a half-century later, with a Los Angeles indie rock band naming itself “Sputnik Monroe” in his honor.

“He was as rock and roll as any of the artists and singers coming out of Sun,” Jerry Phillips told the Commercial Appeal. Phillips, son of Sun Records founder Sam Phillips, was so enthralled with Monroe that he got into the ring as a teenager and wrestled under Monroe’s tutelage as “The World’s Most Perfectly Formed Midget.”

Monroe further infuriated champions of racial purity when he teamed with a young Black grappler named Norvell Austin for a stretch in the early ‘70s. It was one of the first interracial tag teams in the South and, to make things interesting, Monroe talked Austin into placing a blond streak in his hair. Monroe put fuel on the fire when, after disposing of a pair of white opponents, he poured a bucket of Black paint over the head of one of the defeated wrestlers.

“Black is beautiful,” declared Monroe. “White is beautiful,” proclaimed Austin. The two then hugged each other and proclaimed together, “Black and White is beautiful.”

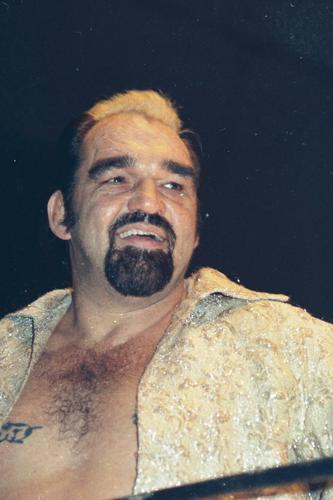

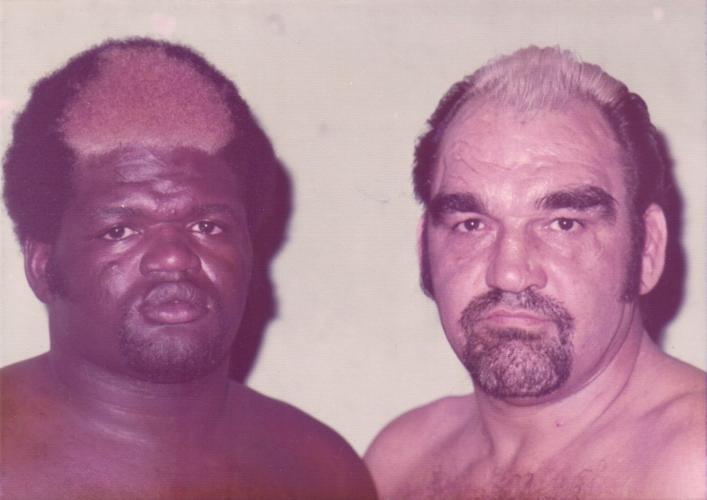

Sputnik Monroe (right) teamed with Norvell Austin in the early 1970s. Provided photo

He did it his way

Sputnik didn’t mellow with age.

He was an authentic tough guy who never caved in to being politically correct. He kept his arresting shock of white hair until it naturally disappeared.

“Sputnik made the most out of what was essentially a little guy,” Russell said of Monroe, who won the world’s junior heavyweight title from the heralded Danny Hodge in 1970. “He would have never made it in the WWE if he was the only heel that ever lived. But he sure was big in his mouth and his heart.”

Monroe was two days shy of his 70th birthday when he wrestled his last match in a small Texas town. His knee gave out for good and, combined with four herniated discs in his lower back and two in his neck, it was time to say farewell.

Monroe spent his post-retirement years in Houston where he worked as a security guard and as a shuttle bus driver for a rental car company at the airport.

Monroe’s last major public wrestling appearance was in July 2005 when he and Billy Wicks reprised their classic Memphis feud at a legends show. The two had set an attendance record for a match in 1959 at an outdoor stadium in Memphis in front of more than 17,000 fans and guest referee Rocky Marciano. (Marciano collected $1,500 for his ref duties, while Monroe and Wicks both got $750). The mark lasted all the way until the Monday night wrestling wars of the late ‘90s.

“He was my ‘Sweet Man,’” recalled Wicks. “In the last five years, we became very close. We’d call each other regularly, and we’d talk about guys in the business and things in the past.”

“I was influenced a lot by listening to him and the stories he told off the camera as much as I was on the camera,” said Russell. “He was a special guy like that. He’d do a lot of things that would irritate the fool out of you. But he was just being Sputnik. He did everything with a splash.”

Folks down South, particularly in Memphis, also still talk about Sputnik Monroe.

“Just last year, we were in downtown (Memphis), and he wanted to go to Beale Street,” Dark recalled in 2006. “And we parked at Peabody Place and walked, and on the way down there at least four young Black kids walked up to him and hugged him and told him their parents had his picture on the wall of their house growing up, that they knew who he was and what he had done.”

Sputnik died in his sleep at a nursing home in Florida, but not before battling the loss of half a lung, prostate cancer, gall bladder surgery and gangrene. Down to 145 pounds and given 72 hours to live, he was brought out of his drug-induced coma long enough to say goodbye to his son, Bubba, who had occasionally teamed with his father in the ‘80s.

Wicks, whom Monroe jokingly referred to as “Granite Hands,” had a bet that Sputnik would read Wicks’ obituary first.

“I called Sputnik up that Friday morning,” said Wicks, who had last talked to Monroe about two weeks before he went into the hospital for the last time. “I’d always call him late in the morning because he would sleep late, but he always seemed to be glad to hear from me. I talked to his wife, Joanne, and asked her how my Sweet Man was doing. She then informed me that he had passed away during the night. I told her he was a double-crosser because we had a deal that he was going to read my obituary before I had to read his.”

“He was a very big-hearted guy, but he was a con man at the same time,” laughed Wicks, who passed away in 2016 at the age of 84. “But I loved the guy. I really cried at first and got very emotional, but now I’m celebrating. Like I told him, he was a hero to me but certainly not a role model.”

The unlikely pioneer lived life on his own terms. But he single-handedly and uncompromisingly bettered the lives of many. He made a bold statement when he refused to perform unless fans, regardless of their race, were allowed to sit anywhere they liked. Wrestling against prejudice, he demanded equal treatment for his Black fans and used his craft to literally fight for social change.

“Like Sputnik used to say, “Often imitated but never duplicated,’” said Wicks.

Sputnik Monroe just may have been the most improbable civil rights hero the South has ever seen.

Reach Mike Mooneyham at bymikemooneyham@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter at @ByMikeMooneyham and on Facebook at Facebook.com/MikeMooneyham. His latest book — “Final Bell” — is now available at https://evepostbooks.com and on Amazon.com

Did you know …

Glenn Jacobs. Provided photo

Two years before Glenn Jacobs first appeared as The Undertaker’s “brother” Kane at the WWF's 1997 Badd Blood pay-per-view, he actually squared off against Undertaker during the late days of regionally based Smoky Mountain Wrestling. Jacobs, working then as the villainous Unabom, fell to the famed Deadman in a cross-promotional match held in Knoxville, Tenn., on Aug. 4, 1995. In some respects, the bout served as a tryout for Jacobs since he subsequently debuted for the WWF as ornery Isaac Yankem and later played a faux Diesel character before being reintroduced successfully as the towering masked Kane. Following a lengthy tenure with the company, Jacobs is back in Tennessee where he presently serves as the mayor of Knox County.

— Kenneth Mihalik

Blast from the Past

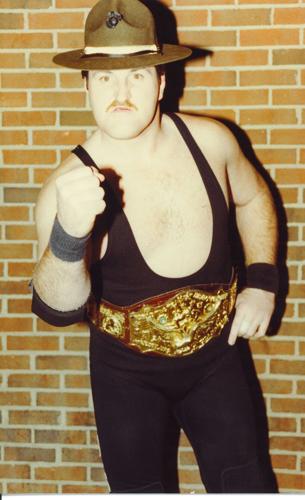

Sgt. Slaughter. Provided/Eddie Cheslock

Before his character Sergeant Slaughter hit the scene in the early 1980s for the WWF and Mid-Atlantic region of the NWA, Robert Remus rose to prominence under a mask as Super Destroyer Mark II, a methodical bully, with the American Wrestling Association (AWA) during the late ‘70s. He demonstrated ample talent to earn a strong push and position as Sgt. Slaughter, a rogue drill instructor from Parris Island, S.C., and high-ranking contender to WWF champion Bob Backlund. During this stay, he also competed in a hot feud, culminating in a memorable “Boot Camp Match” at Madison Square Garden, versus Pat Patterson. His reputation as a strong heel grappler cemented, he invaded the territory operated by Jim Crockett Promotions next. Though Sarge and Don Kernodle formed a successful and fiery tag duo, he also found time to engage in solo battles against premier stars such as Ricky Steamboat and Wahoo McDaniel.

Slaughter returned to the WWF as a fan favorite in 1983, riding a wave of patriotic popularity that rivaled Hulkamania in mainstream appeal. With his signature “Cobra Clutch” as a finisher, that run lasted a year in tussles against the Iron Sheik and Nikolai Volkoff. Unfortunately, Sarge’s outside activities in entertainment, resulting in him becoming a crossover pop culture hero with the G.I. Joe franchise, also paved the way toward a merchandising dispute with, and abrupt exit from, the WWF in late 1984. There was a fallback alternative. He managed to convene a recurring stay in the spotlight with the AWA as a main-eventer, including its affiliation with the Pro Wrestling USA contingent as they promoted cards in the WWF’s Northeastern base. That venture ultimately collapsed, but Slaughter stuck with the AWA through its lean times and final hurrah as the decade ended.

A truce was forged with Vince McMahon in 1990, but under the condition that Slaughter return to the WWF as an “Iraqi sympathizer” with the U.S. then embroiled in the Persian Gulf War. This controversial anti-American change positioned the Sarge as a top heel once more. He defeated The Ultimate Warrior in January 1991 for the company’s world title, holding the belt until Hulk Hogan dethroned him at that year’s Wrestlemania. Eventually, Slaughter saw the light after Summer Slam and reverted to fan favorite. He challenged and scuttled former allies Colonel Mustafa and General Adnan, then teamed with Hacksaw Jim Duggan in bouts through 1992. A final major singles’ program took place opposite The Mountie, with the majority of victories corralled by the Canadian star.

Though he didn’t wrestle as a regular beyond that period, Slaughter remained with the organization in a variety of contexts, on and off camera. As one of the company’s longtime major professionals, induction to the WWE Hall of Fame (Class of 2004) was inevitable. Now 72, Sgt. Slaughter has long been considered one of the industry’s enduring icons.

— Kenneth Mihalik

Photo of the Week

Bill Moody, better known to wrestling fans as Paul Bearer, poses with his urn at a convention in 2010. Moody passed away in 2013 at the age of 58. Provided photo