Making New Elements Doesn’t Pay. Just Ask This Berkeley Scientist

Theorists agree that 119 and 120 are probably within reach, but discovering them will mean wasting time and money.

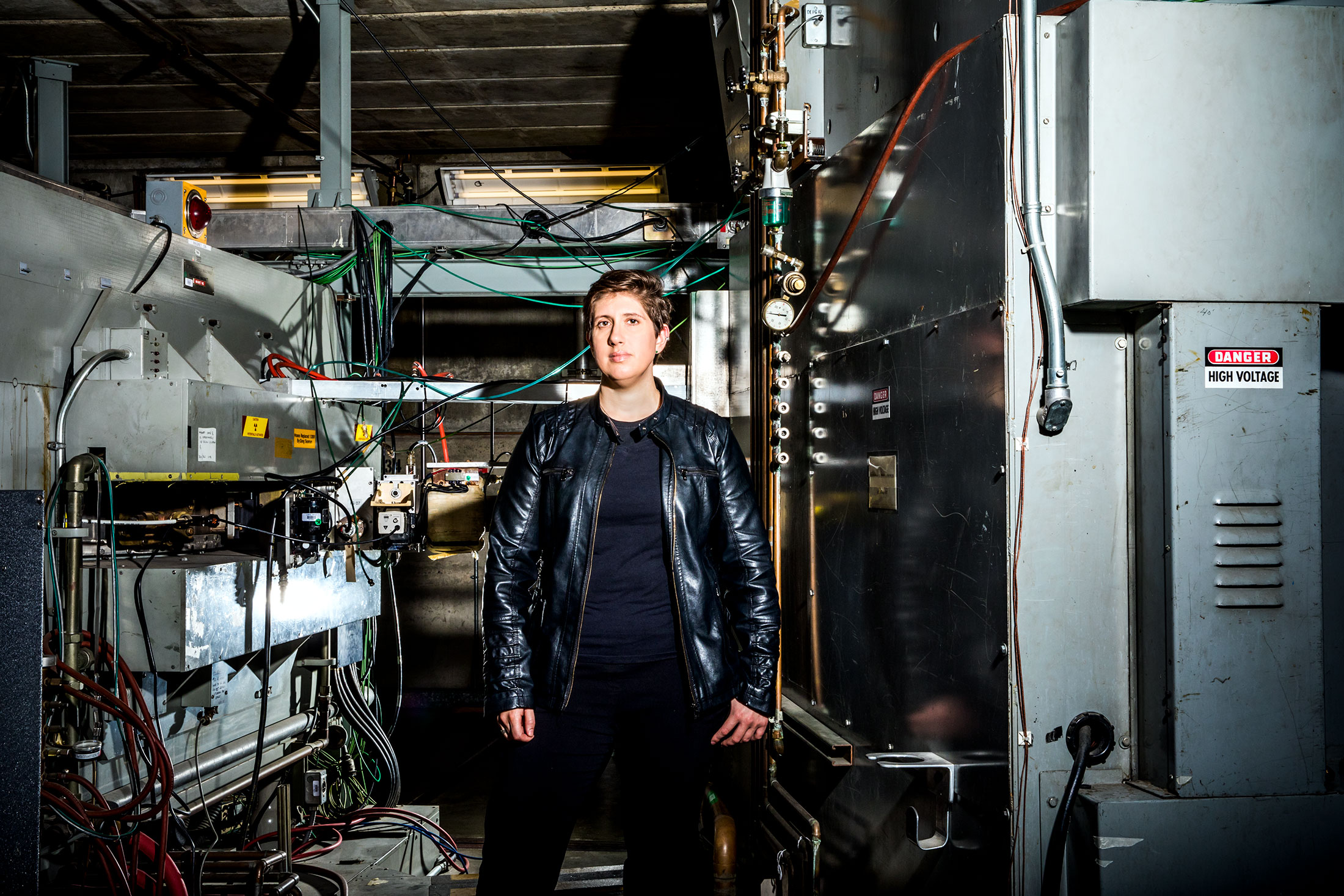

Jacklyn Gates at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Photographer: Christie Hemm Klok for Bloomberg BusinessweekSo here we are, at the edge of chemistry: atomic No. 118, oganesson, the coda of the periodic table as it stands and the spot where questions of science shade into those of philosophy. Is an element really an element if it exists nowhere in nature—if it can be engineered only in a lab for a fraction of a second before it blinks out of existence? Is “discovery” the right word for such a feat? How far can scientists extend the table by mashing lighter elements into each other to create heavier ones? Is it even worth the time and trouble to do it just to add a square?

One place to find answers to these questions is on Cyclotron Road, a calf-busting walk up a hill above the University of California at Berkeley campus. For decades, Berkeley’s tremendous accelerators—which hosted within their guts the collisions and combinations of high-energy particles—produced a parade of elements the world had never known: 15 of them, including every element save one from atomic No. 93 through 106. They came to be called superheavies, though this was always an imprecise term, referring variously to elements above 92, or above 100, or above 103.