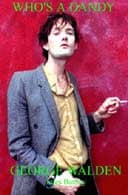

Who's a Dandy?

by George Walden

180pp, Gibson Square Books, £12.99

The strangest legacy of Beau Brummell, king of the Regency dandies, is not his influence on sartorial style but his effect on writing. No sooner does an author touch the subject of the Beau's invention of starched neckties, whose height and stiffness "created a sensation equal to Waterloo", than his hand grows light and sentences of the most nimble and economic elegance curl and drop from his pen. It is as if the Beau's rules about dress - that supremacy lies in the finest cloth and cut, in the flawless perfection of the finished look, in understatement ("If John Bull turns round to look at you then you are not well dressed") - were transposed to literary style.

Brummell's first biographer, Captain Jesse, failed to reach the required level of sublimity in addressing his subject, and he besmirches the Beau with his lumpen and long-winded prose (Thomas Carlyle later did the same, calling the dandy nothing but a clothes-wearing man). But then came Jules Barbey-d'Aurevilly with his exquisitely tailored essay, "On Dandyism and George Brummell" - finely translated in this book by George Walden - and the dandy was once more untouchable. "Dandyism is a whole way of being," Barbey proclaimed, "entirely composed of nuances". Dandyism is the last spark of heroism amidst decadence: "Dandyism is a sunset."

Baudelaire followed, heralding the dandy as the dangerous product of a society in transition, the figure who, with one flick of his little finger, dispenses with the dry dust of aristocracy and establishes his own peculiar laws of precedence. Virginia Woolf's essay on Brummell is the finest she ever wrote. "Empires had risen and fallen while he experimented with the crease of a neck-cloth and criticised the cut of a coat." Camus saw the dandy as romanticism's "most original creation", exemplifying its concern with "defying moral and divine law".

All this eloquence for a man who placed himself above society by spending most of the day dressing and the rest of it being dressed, who was left by his titled friends to die in a madhouse in Caen because eventually, when the clothes fell away, George Bryan Brummell was no more than a bourgeois upstart.

Walden, a former Tory MP, is aware that in daring to write about Brummell and dandyism he is nudging his way into a select group of sacred and sometimes canonical texts. He comes to the shrine to worship not only Brummell but also Barbey, whose essay he calls "the most penetrating and original study of dandyism ever written". The premise of Walden's argument is that the three things that sum up our age are "science and technology, neo-liberal politics, and an infatutation with fashion and style - and the importance of the latter can only be properly understood through a reading of Barbey on Brummell".

Walden goes on to consider the re-emergence of the dandy in modern times and what his eminence might signal about "the decadence of democracy". Andy Warhol's authority, like Brummell's, rested "more on presence than on words", and his artistic genius was likewise democratic to its roots, consisting of "glorifying the ordinary". Warhol's screen prints of Marilyn Monroe had the same effect on the crowd as Brummell's flawlessly knotted ties: they both "exploited the yearning for stylishness in an age of mass consumerism".

Walden notes literary dandies (Nabokov, Amis), foodie dandies ("who elevate gastronomy from taste into art") and pop dandies (Jarvis Cocker). He is careful to dissociate the austerity of dandyism from the excesses of camp, to distinguish between the fashion-conscious man and the thorough-going dandy.

Walden's is a smart and timely essay, introducing a brief masterpiece. One of the pleasures of this beautifully produced book is its invitation to consider the language of style and its reminder that, as Oscar Wilde said: "It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The true mystery of the world is the visible and not the invisible."

· Frances Wilson's biography of Harriette Wilson is to be published by Faber next year