Can Openers are an Innovative, Crucial, but Oddly Low-Quality Everyday Tool

I hope it’s no character flaw, but I seem to go through a lot of can openers, searching for that mythical perfect device. They’re so ubiquitous that you’d be forgiven for not giving them a second thought. Inventive, for they make use of some basic physical principles to pierce metal, using hand-power alone. Necessary, for the contents of any can are as remote as a distant country without one. Despite their place in our material culture, most recent can openers are oddly low-quality tools. They often fail to effectively do their single core ‘job-to-be-done;’ opening a can.

Instead, we’re left to fish razor sharp lids out of the can. Some models, especially those that drag a sharp wedge through the lid might leave small fragments of metal that can then break off into our dinner. Other versions scar the interior of the can, distributing the can liner into our food. I’ve got a bit of an obsession with can openers. Specifically with mechanical can openers, those powered by human hands, rather than electric variants. I’m curious where they came from, but also how they seem to have frozen in time; failing to be improved by any innovation.

I’d like to ‘open up’ the story of can openers (can opener pun?), starting with a little basic context about the can. I think the failure of everyday can openers to much improve beyond their invention can tell us a lot about a whole class of made things that have become cheap and disposable commodities. It describes an arc of an invention where it reaches some sort of complacent plateau, from which only a step-change in thinking will break it free.

The context of the cans and canning

Cans feel like old technology, but the modern can is, at best, a hundred or so years old. Canning is the process of preserving food in tough, airtight containers. The food has usually been pasteurised - heated and cooled - as part of the process; often in the can itself.

Canning can be distinguished from pickling and fermenting, two other food preservation technologies I’ve written about before. Both of which are far older, and in many ways, for more healthy for the quality of food they preserve. Canning, if it has a distinct advantage, creates a food storage container that is unusually robust and can preserve foods longer without intervention than most systems. The only exceptions might be freeze-dried foods, which, to be fair, are often canned.

The French government, in 1795, was the first to make the issue of food preservation a state priority, with their offer of a cash prize for anyone who that could develop the best method for preserving food. Their interests were obvious. France was about to enter the turmoil of the French revolution and a few years from Napoleon taking power. French soldiers needed rations that were shelf stable without refrigeration, and that still preserved as much of the nutrients and aesthetic potential of food as was possible. As they say, an army marches on its stomach.

The Frenchman Nicolas Appert, with experience as a chef, distiller and candy-maker, answered the call. Over nearly two decades he experimented thoroughly with the chemistry and physics of food preservation. His insights came together in a great work of several hundred pages, “The Art of Preserving All Kinds of Animal and Vegetable Substances for Several Years.” I can’t do Appert justice here so will leave him for another time.

Needless to say, Appert’s conclusions are familiar to us, even across the centuries. His most successful experiments proposed a method of heating food in glass bottles in a boiling water bath. Once the bottles reached temperature and the food was cooked, the containers were quickly stoppered and the bottles cooled. The cooling action drew in the sealing, creating the airtight ‘canning’ process that we’re familiar with today. Appert notes:

“The beef which I had taken out when three-fourths done, I put into jars which I filled up with a part of the same broth. Having corked, luted and tied up these, and wrapped them in bags, I placed them and the bottles containing the broth, upright in a cauldron… I filled this boiler with cold water [and]… I heated the boiler… The next day I besmeared the corks with rosin [resin] in order to forward the bottles and jars to different sea-ports. At the end of a year, and a year and a half, the brother and boiled meat were found as good as if made the day they were eaten.” (Appert, p. 42 - 43)

Canning innovations didn’t stop with Appert and the French. The British, with their own martial ambitions, were quick to pick up the technique. In 1810, English merchant Peter Durand patented his own food storage boxes, swapping out the glass used by Appert with metal.

These original cans were by no means replicas of what we have today. Beyond Durand, the first metal tins and cans were usually made of strong metals, like iron, lined with tin, and welded shut. At 4 - 5 mm thick, they were like little ‘food safes’ as much as they were cans.

The concept of ‘caveat emptor’ (buyer beware) comes to mind when opening these first tins and cans. Aside from vague advice to employ a hammer and chisel, it was really left to individuals to develop their own techniques for accessing the food within. As you might imagine, a hammer and chisel are a difficult combination to use on a slippery, tough and strong can.

For these first few decades, from the early 1800s, canned food likely remained more of an oddity item. Both due to small production volumes, but also the outright difficulty in getting into them. This difficulty likely influenced can manufacturers to shrink cans and to make their materials thinner.

Increases in the quality of metals available, like the wider use of steel, and better forming technologies allowed cans to become more like the objects we’re familiar with today. There are wonderful details on a modern can, like the parallel sets of extruded grooves and humps that ring the surface. These increase the stiffness in the can’s walls, lid and base, allowing thinner metal to be used to form the overall can.

Christopher Roosen (© 2022) Can

The binding rim of the can is also worth attention[ Folded over rim wall… ]. The lip of the can is actually folded over the lid in a complicated arrangement that ensures the sidewall is folded into the lid in several layers. However, the lack of cans was only one factor in the story of this set of related innovations. For a few decades, cans awaited suitable openers.

The first ur-Openers

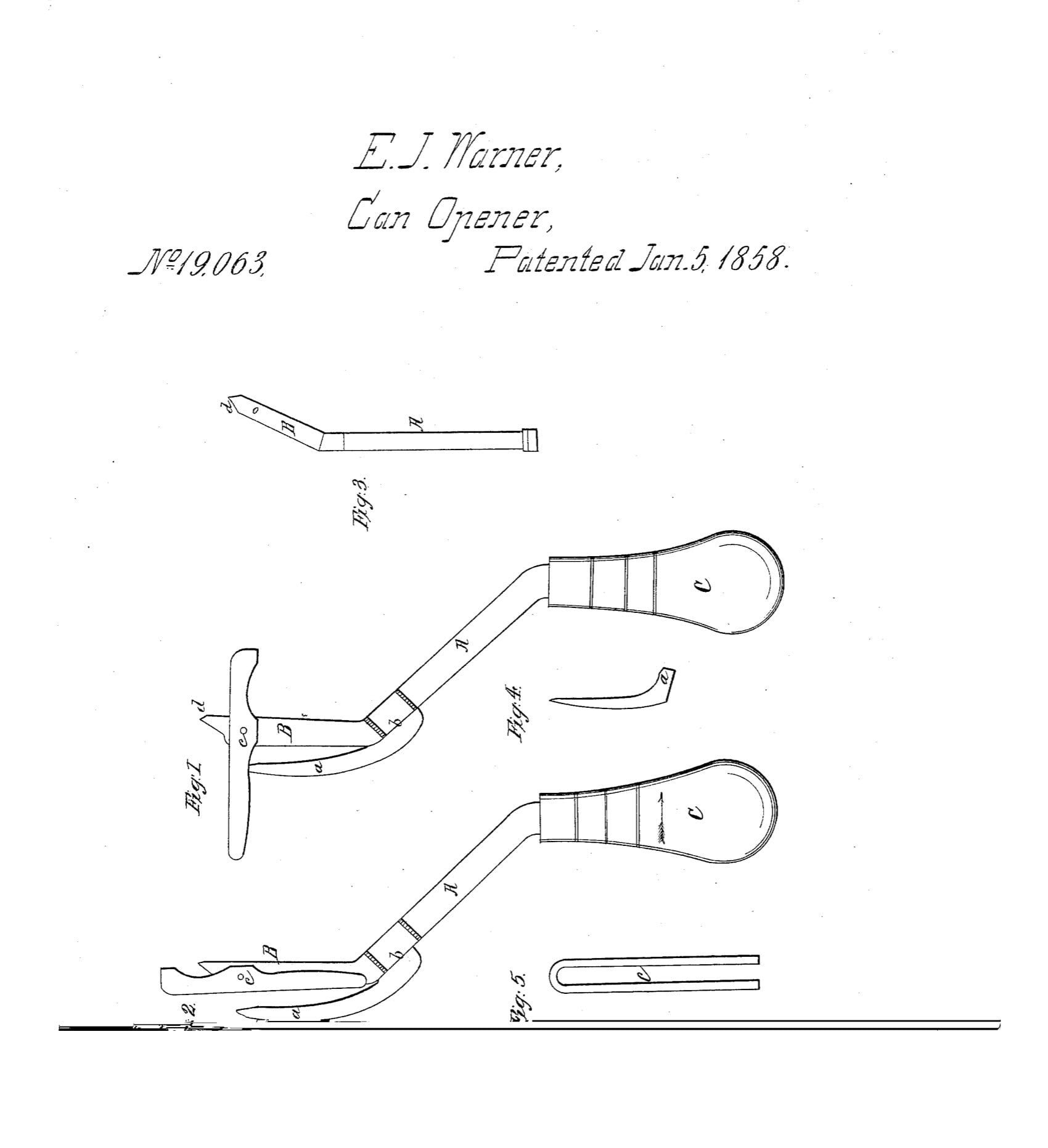

Let’s set aside the hammer and chisel as can-opening tools. These were common tools being repurposed for the can. The common story is that the first purpose-designed can opener was patented in 1858, in the United States, by American inventor Ezra J. Warner.

Warner (1858)

With its long handle and sharp blade, it looks as much like a weapon of war as it does a humble can opener. In fact, it was adopted mostly by the Northern Army during the United States Civil War as Warner’s opener was too difficult for everyday use.

A fascinating and exceptional alternate line of research by Samuel J. Hardman writing in the UK, “Tools and Trades History Society,” suggests an alternate timeline for these early can openers. Hardman proposes that it was actually Robert Yates, an instrument manufacturer in the United Kingdom gained a patent for an improved can opener in 1855 and his son, Frederick Green Yates, patented an even earlier knife-opener in 1851.

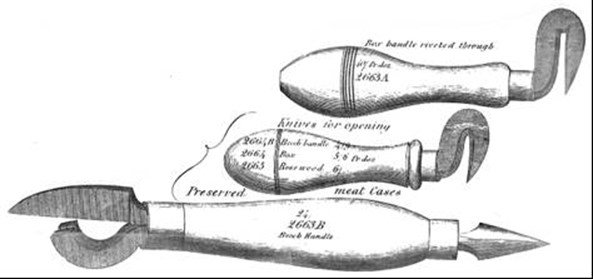

Yates-style openers are interesting, because they seem a great deal like models made even today, with long bayonet blades and ‘stirrup’-like saddles to pinch upon the can.

Yates Snr. was a cutlery and surgical instrument manufacturer, so his skill (and presumably that of his son) makes sense. Yet, again, thanks to Hardman’s exceptional research, there might be two even earlier examples of can openers.

The first, by John Gillon of the United Kingdom, was a ‘hook-knife’ can opener in 1840, evidence of which comes from a Victorian tool catalogue; “The Victorian Catalog of Tools for Trades and Crafts,” by Richard Timmins & Sons in 1845, reprinted by Studio Editions in 1994.

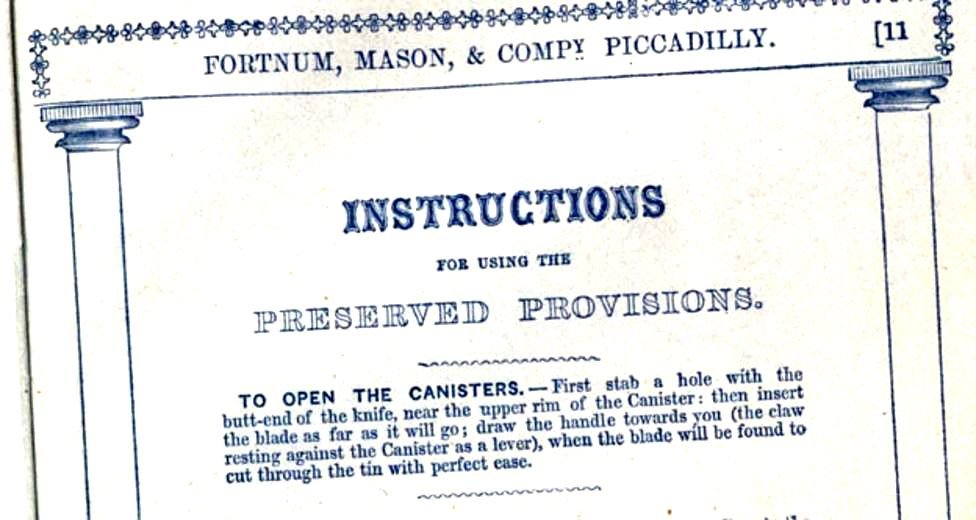

The second, more circumstantial evidence comes from the Fortnum, Mason & Company Piccadilly, whose instructions for opening ‘canisters’ is as follows:

“To open the canisters. - First stab a hole with the butt-end of the knife, near the upper rim of the canister; then insert the blade as far as it will go; draw the handle toward you (the claw resting against the Canister as a lever), when the blade will be found to cut through the tin with perfect ease.” (Fortnum and Mason)

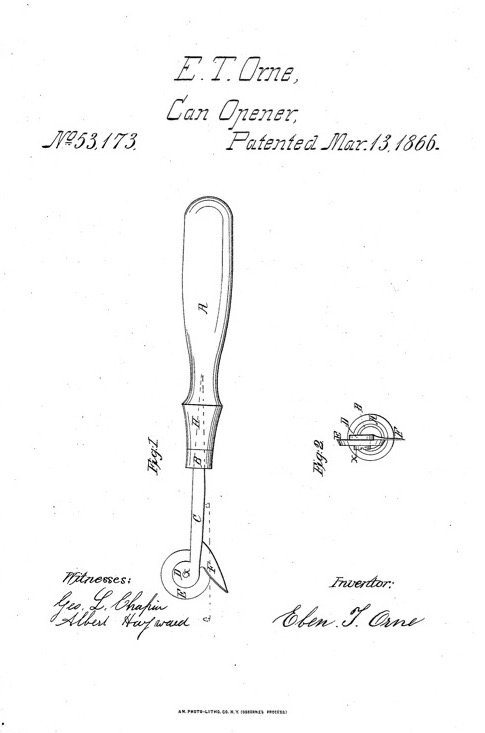

This description seems to imply some sort of clawed device that is surely not just a knife. It also sounds painful if a mistake is made when opening the can. By the 1860s, a whole plethora of can openers began to appear, like this United States patent by Orne in 1866.

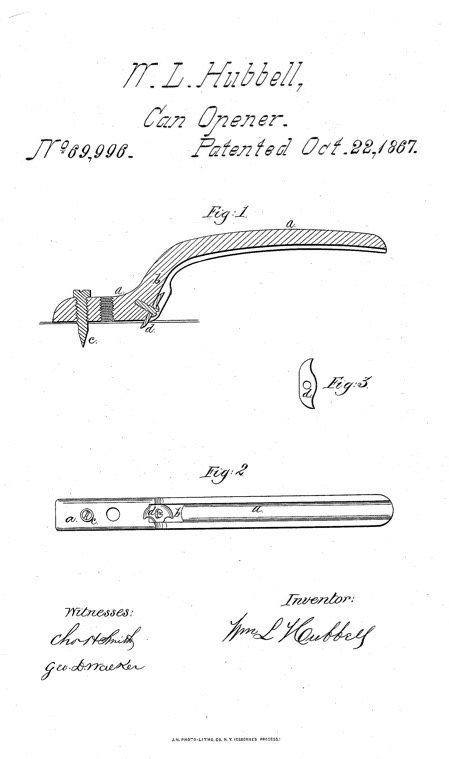

…and Hubble in 1867.

From the 18th through to the 19th century, this trend in wrench-like, knife-oriented can openers continued, with some interesting exceptions and variations, like the miniaturised American P-38 ration-tin opener.

Welcome to circular rotation

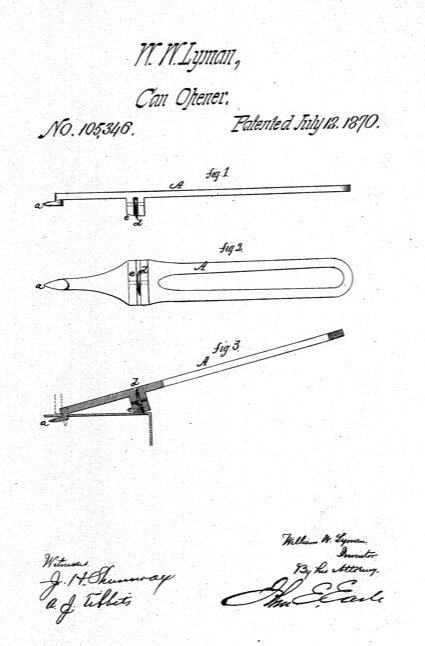

Back in the United States, William Lyman is generally credited, in 1870, for inventing the first rotating can opener, although its ease of use leaves something to desire.

“To use the instrument, press the point through the cover… then turn down… so that the point will [punch] below the cover and the pivot pass through; then press the cutter down onto and through the metal, running the handle around, and the revolving cutter cuts through the metal.” (Lyman)

It wasn’t until another dozen years or so in the future, in the 1920s, that we began to see the first rotating gear can openers; the birth of our modern can opener.

The rotating gripper

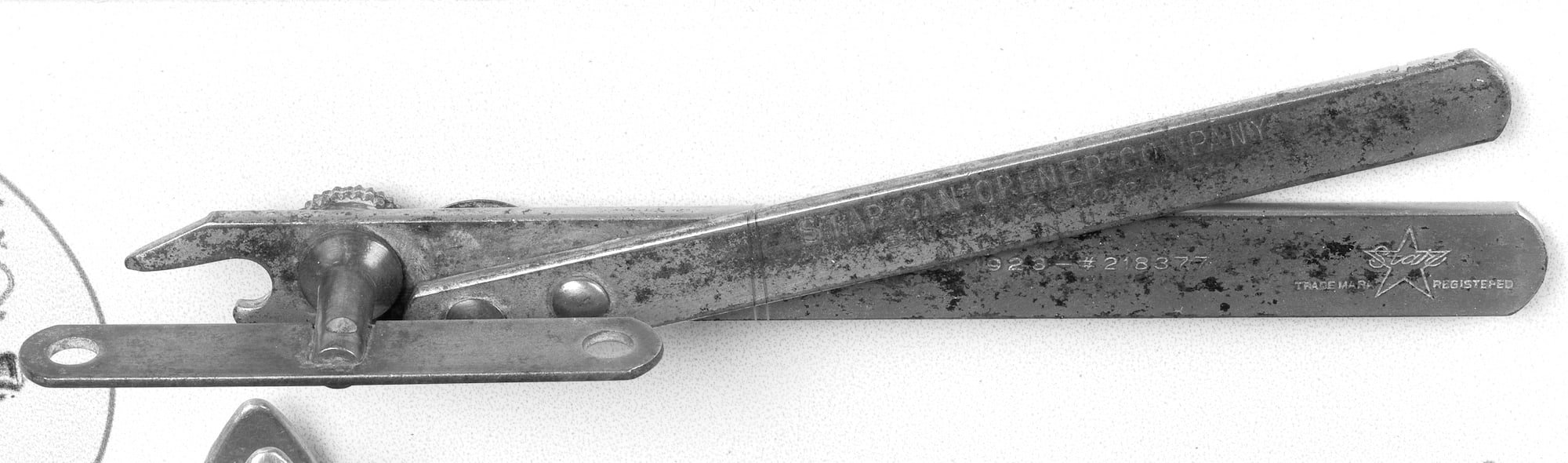

Like much of this exploration of can openers, who was first with an invention is often up for debate. In the case of a rotary cutter, the first inventor appears to be the Star Company in San Francisco. They built out an extension of the Lyman concept, using a driving gear wheel to push the wedge through the lid.

The Star opener reminds me a lot of the New Zealand can openers I first encountered more than twenty years ago, an interesting technological throwback, perhaps.

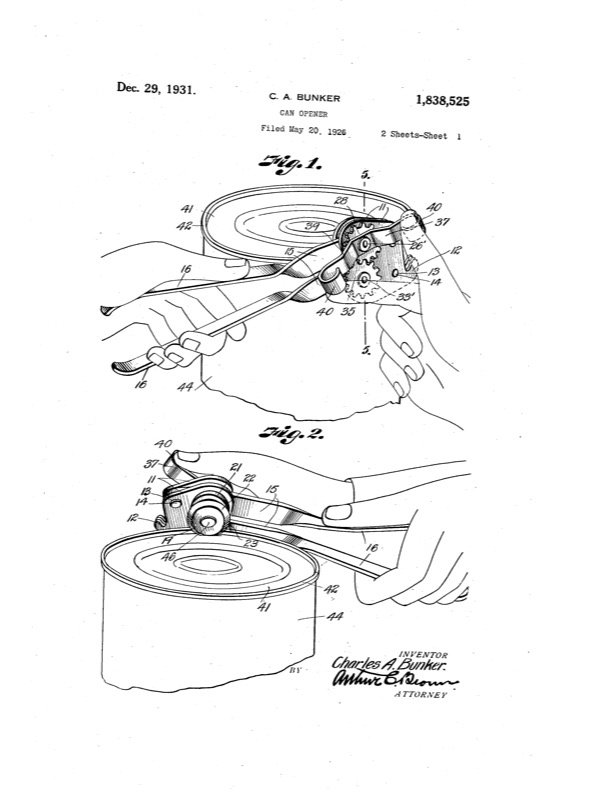

Then, with great flourish, came the ‘Bunker’ opener in 1926, in which we see the birth of the gear and wheel driven rotary cutters.

There’s something interesting about the Bunker patent. Though the patent is nearly 100 years old, the drawings could almost be seen as modern.

I mean it’s all there. The gears, the grip wheel, the twisting butterfly handle, the two grips that drive a circular piercing blade down into the top of the can. It looks just like something we’d recognise today as a can opener. It’s as if can opener thinking stopped at this point. Both Star and Bunker designs, and many others like them, can still be found in stores today. At least, that’s part of the story.

Side trip with side-mounted safety can openers

First appearing in the 1980s, like this early example by Paul Porucznik and Keith Longstaf of England, this new approach abandons access through the top of the can for an approach through the side of the can; not just through the sidewall of the can itself, but the actual seam through which the lid is joined to the can body.

This type of opener is often called the ’safety opener,’ for how it removes the lid, leaving no sharp lid to fall down into the food, and a reduction in edge on the can itself. It does, however, have some cons, for it can leave little burs of metal that come up off the can itself. Oddly, this type of side-mounted safety opener hasn’t really made much penetration into the market in the forty years since its introduction.

The modern ‘disposable’ can opener

This brings us all to the modern can opener, in particular, two models; one the ‘rotary wheel cutter,’ like the Bunker can opener line of thinking.

The other, the rotary ‘drag a knife,’ model, like the San Francisco Star company can opener.

On my rotary wheel opener

For a while at least, the rotary wheel opener, I bought inexpensively at a local supermarket, seemed to do the job it was designed for, aside from dropping the sharp can lids down into the can. However, due to its narrow toothed wheels and weak handle design, over the months, the handles stopped exerting the force required to ensure the rotary cutting wheel bite into the surface. This caused the cutting action to ‘skip,’ leaving whole sections of the can uncut.

The narrow angled gears, which had just enough purchase when the device was new, began also to skip and churn as they moved outside tolerance. The end result, about half a year after buying the device, is that it is nearly useless when it comes to opening a can.

In exploring can openers, I did discover that there is a resurgent ‘life hack’ movement dedicated to winning people over to using normal can openers in sideways operation; cutting into the side wall of the can, rather than into the top lid.

Having tried it a few times, I can attest it works. Sort of. However, it doesn’t cut through the seam, like the intentionally designed safety can opener, which means the action can raise large metal shards. These may or may not risk falling into the food.

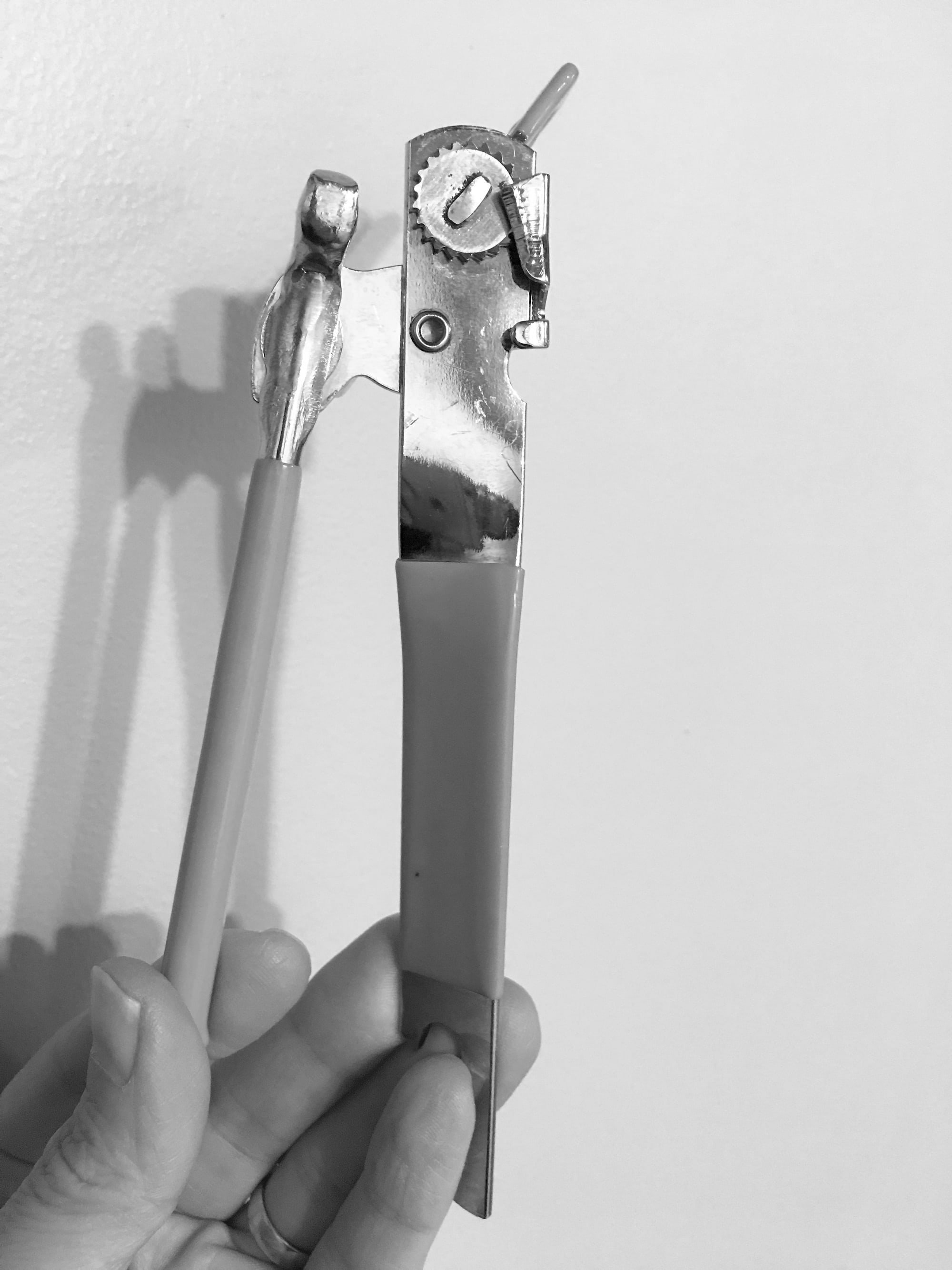

Or, my knife wedge opener

A much cheaper, ‘classic’ design that I talked about earlier is the New Zealand ‘knife wedge’ design. On the surface, it seems a more robust design, though this might be nostalgia talking.

Turning the handle crank causes the angled knife wedge to drag through the can. This design takes us all the way back to openers back in the early 1900s. The funny thing is that the action, even after a year or two of intermittent use, still opens cans better than the now-broken rotary cutting wheel design. Except for one crucial failing.

Consider the cutting edge and imagine its passage across the inner portion of the can. Because of the tight tolerances required for the device to work, as the can opener drags its wedge, it can’t help but interact with the can’s side wall. I noticed this when I started using it on any can that had a white inner liner. In effect, the opener ‘scrapes’ fragments of the can liner into the food, which requires you to either carefully fish the little plastic fragments out of the canned goods, or assume they will ‘pass through the system.’

How did we end up here? When cans have seemingly reached manufacturing perfection, two hundred years past their introduction, how have can openers fared so poorly?

I have a theory that the very ubiquity of the can opener renders it fundamentally prone to two countervailing forces; unattractiveness to innovation and commoditisation.

Forces of can opener mass production meet cultural disregard for cans

Can openers are a common and inexpensive tool. Commoditisation pressures have ensured that can openers are made at the lowest possible cost and sold as such. As such, the online world is full of people lamenting modern can openers.

Advice includes trying to find pre 1980s can openers in secondhand stores, for their superior action and better build quality. Cheaply-made can openers are also less likely to consider changing human needs; especially those with accessibility issues; either reduced grip string to ‘pierce’ the can, or reduced hand strength to crank the handle.

There is also the cultural consideration. At times, canned food attracts strong sociocultural judgement, sometimes forming an association with those not wealthy enough to be able to procure fresh foods for all their supplies. This is a shallow and unfair judgement. There are many cases when it is perfectly reasonable to use a canned good over a fresh supply. Some foods change in a useful way when canned, creating a new food consistency or a taste that recipes require. Not everyone can afford the time or cost of ingredients to make tomato paste from scratch each time.

A cultural judgement of canned food is also not well suited to a time of uncertain food supplies. Canned goods might make a comeback when people need to ensure they have a shelf-stable food supply to buffer food supply uncertainties. I know I’ve bought a lot more canned goods over the past two years than ever before.

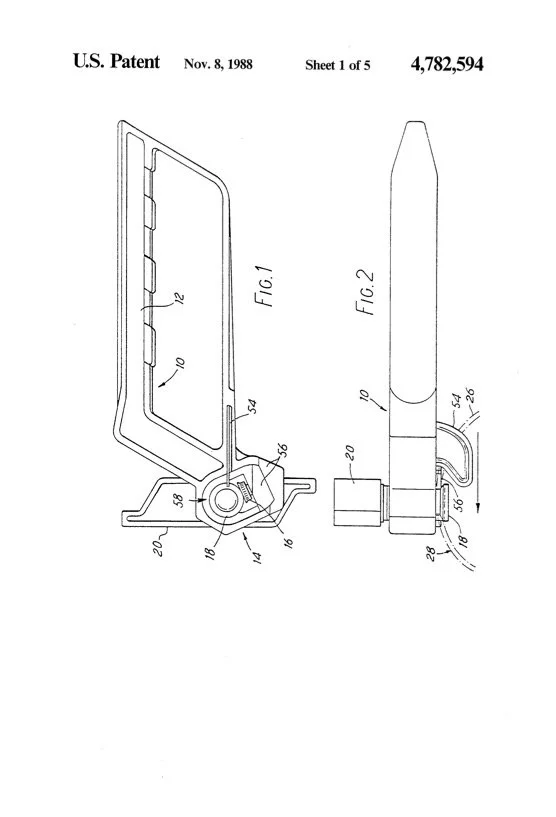

The can, and more importantly, the can opener is just disregarded. It is a technological investigation that somehow entered its endgame decades ago. Patents are still granted for can openers. Like this one by Kalogroulis and Mah:

Whether these innovations are better or worse is hard to tell, for they rarely seem to make it into the wider marketplace.

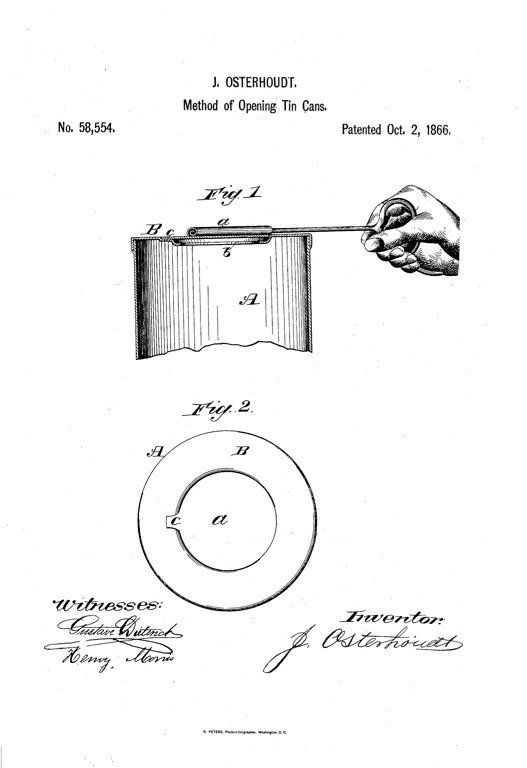

Which begs the question: is it perhaps not the can opener, but the can, that is the problem? As much as we haven’t innovated the can opener, we definitely haven’t made much traction on the can. As far back as 1866, Osterhoudt patented a tear-strip method of entering cans that did away with the opener entirely.

Consider the Osterhoudt pull-strip can in the context of the many ‘pull-lid’ cans that we find on the shelves today. When a pull-lid works well, we get instant access to the can without any need of equipment. Assuming of course that it works and the lid-ring doesn’t snap off! In that case we might resort right back to a can opener.

Where do we go from here in the world of cans and can openers? Is a sealed vacuum pouch the modern extension of canned goods? In a world saturated with plastics, probably not. Back to glass? That has its own problems. In an ideal world, I’d love to see an enterprise mechanical engineer or backyard inventor decide that the problem irritates them enough to invent a better can opener that doesn’t strip the cans, leave metal fragments a risk and lasts for years.

Meanwhile, I’m off to the store to buy myself another can opener.

References

Readings

Appert, N. (1811). The Art of Preserving All Kinds of Animal and Vegetable Substances For Several Years. London, Black, Parry and Kingsbury.

Eschner, K. (2017, August 24). Why the Can Opener Wasn’t Invented Until Almost 50 Years After the Can. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-can-opener-wasnt-invented-until-almost-50-years-after-can-180964590/

Food Museums of the Province of Parma / Musei del cibo Pomodoro. (2022, July 11). The History of the Can Opener. Google Arts & Culture. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/the-history-of-the-can-opener/TQIyTv3nPqXlLQ

Geoghegan, T. (2013, April 21). The story of how the tin can nearly wasn’t. BBC News Magazine. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-21689069

Hardman, S. J. (2017). History of the Can Opener. https://www.taths.org.uk/images/TTArticles/Canopener/CanOpenerMayRevised2.pdf

Inglis-Arkell, E. (2017, November 28). Don’t lose a finger: The 200-year evolution of the can opener. Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2017/11/dont-lose-a-finger-the-200-year-evolution-of-the-can-opener/

Jar & Can. (2021, July 11). Short History of Can and Can Opener. Jar & Can. https://jarandcan.com/history-of-can-and-can-opener/

Various. (2007). The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink (A. F. Smith, Ed.; Second Edition). Oxford University Press.

Watson, A. (2022, January 15). Lessons from a Can Opener (Video). Technology Connections via YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i_mLxyIXpSY

Pictures

Bunker, C. A. (1926). Can Opener (Patent No. US1838525A). United States Patent and Trademark Office. https://patents.google.com/patent/US1838525A/

FieldMarine. (2008, November 21). P-38 American Tiny Can Opener (Image, CC BY-SA 3.0). Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:P-38_can_opener.jpg

Food Museums of the Province of Parma. (2016, February 25). Lever Can Opener - Apriscatole a Leva (Image, CC BY-SA 3.0). Food Museums of the Province of Parma via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apriscatole_a_leva_-_Musei_del_cibo_-_Pomodoro_-_034.jpg

Food Museums of the Province of Parma / Musei del cibo Pomodoro. (2016, February 25). Butterfly Can Opener - Apriscatole a Farfalla (Image, CC BY-SA 3.0)). Food Museums of the Province of Parma via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apriscatole_a_farfalla_-_Musei_del_cibo_-_Pomodoro_-_058.jpg

Hubbell, W. L. (1867). US69996A - Improvement in can-openee - Google Patents (Patent No. US69996A). United States Patent and Trademark Office.

Kalogroulis, A. J., & Mah, P. Y. (2014). Can Opener Mechanism (Patent No. US20160368750A1). United States Patent and Trademark Office. https://patents.google.com/patent/US20160368750A1/

Lyman, W. M. (1870). Improvement in Can-openers (Patent No. US105346A). United States Patent and Trademark Office. https://patents.google.com/patent/US105346A

Orne, E. T. (1866). Improved Tin-can Opener (Patent No. US53173). United States Patent and Trademark Office. https://patents.google.com/patent/US53173A/

Osterhoudt, J. (1865). Method of Opening Cans (Patent No. US58554A). United States Patent and Trademark Office. https://patents.google.com/patent/US58554A/

Richard Timmons & Sons. (1845). Trade Catalog of Richard Timmons & Sons - John Gillon Can Opener (Image, Public Domain).

Warner, E. J. (1858). Can Opener (Patent No. 19063). United States Patent and Trademark Office. https://pdfpiw.uspto.gov/.piw?PageNum=0&docid=00019063&IDKey=06E4E2F0E626%0D%0A&HomeUrl=%2F%2Fpatft.uspto.gov%2Fnetahtml%2FPTO%2Fpatimg.htm

Christopher Roosen © (2022) Modern Can Opener

Christopher Roosen © (2022) New Zealand Can Opener

Christopher Roosen © (2022) Cans

Did you find this article valuable? Consider supporting our ongoing Adventures

Adventures in a Designed World is my labour and love and one where I’m committed to human-generated ideas, content and imagery. I spend many hours and dollars each week to research, write, polish and host high-quality insight. If you have the capacity, I'd appreciate your support to allow me to keep giving you interesting insights about our complex relationships with technology. ~Christopher