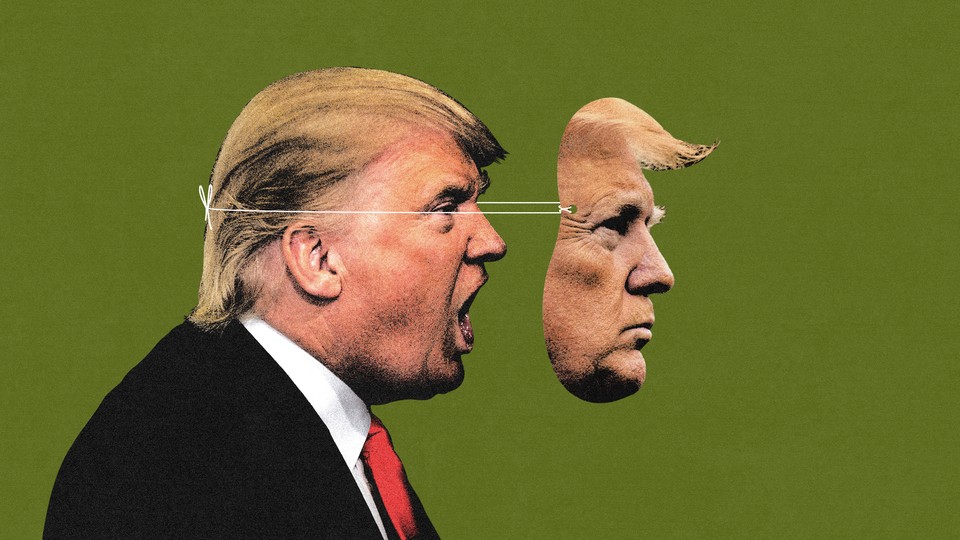

The Trump You’ve Yet to Meet

Just because we know bad things about the 45th president, don’t assume that there’s nothing bad left to find out.

How well do we know Donald Trump? Pretty well, it would seem. Nobody has ever accused the outgoing president of possessing a complex personality. His behavior in office confirmed the common view, barely disputed even by his allies, that he is a shallow narcissist, blind or indifferent to common decencies, with poor impulse control and a vindictive streak. His futile attempt to litigate away electoral defeat may appall you, but it probably doesn’t surprise you.

Still, just because we know bad things about the 45th president, don’t assume that there’s nothing bad left to find out. Journalists like to pretend that we know everything about a president in real time, but our information is never close to complete. There’s always more to learn, and it’s seldom reassuring.

Americans had no idea until after he left office how completely Woodrow Wilson depended on his wife, Edith, after he suffered a stroke in September 1919; she waited two decades to admit in her memoirs that, on instructions from Wilson’s doctors, she’d winnowed his written communications with Cabinet members and senators, digesting and reframing “in tabloid form those things that … had to go to the president.”

Nor did Americans learn until a decade after his death that John F. Kennedy, a much less devoted family man than Life magazine let on, shared a mistress (sequentially if not concurrently) with the Chicago Mob boss Sam Giancana, whom the CIA recruited in one of several harebrained plots to assassinate Fidel Castro.

Then there’s Richard Nixon. Americans knew many shameful things about Nixon thanks to the Watergate investigation that prompted his resignation. But only after he left office did we learn, for instance, that Nixon ordered an aide to compile a list of Jews who worked at the Bureau of Labor Statistics so he could demote some of them.

Nixon represents the gold standard in postpresidential shockers. Decades after he left the Oval Office, gasp-inducing revelations from his White House tapes and other documents continue to stream forth. As recently as September, the Princeton political scientist Gary Bass revealed that the president who engineered a 1971 tilt in U.S. foreign policy away from India and toward a repressive junta in Pakistan told aides that he found Indian women sexually repellent.

India at the time was the rare nation led by a woman, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Gandhi had angered Nixon by strengthening India’s ties to the Soviet Union as she prepared to go to war with Pakistan to support a rebellion in East Pakistan, which later became the independent nation of Bangladesh. At the time, it was abundantly clear that Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, judged Pakistanis’ slaughter of Bengalis to be a Cold War sideshow. But Americans had to wait half a century to discover the psychosexual component of Nixon’s cold-blooded realpolitik.

“Undoubtedly, the most unattractive women in the world are the Indian women,” Nixon can be heard saying in a tape recording from June 1971 that the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum released in response to Bass’s declassification request. “The most sexless, nothing, these people. I mean, people say, ‘What about the Black Africans?’ Well, you can see something, the vitality, there. I mean, they have a little animallike charm. But God, those Indians, ack, pathetic.”

This was no momentary lapse. During a break in a November, 1971 summit with Gandhi, Nixon returned to the topic, saying, “To me, they turn me off. How the hell do they turn other people on, Henry? Tell me.” And finally this gem worthy of serious historical analysis: “They are repulsive and it’s just easy to be tough with them.” (Kissinger, who’s always maintained, falsely, that he discouraged Nixon’s bigoted rants, can be heard in these tapes egging on his boss.)

Don’t blame yourself if you missed this shocking bit of Nixonia when it surfaced a couple of months ago. Odds are you were distracted by some other real-time outrage. When a public man is known to say bigoted things out in the open, it’s near certain that he’s saying even more bigoted things in private. Will we hear about these after Trump leaves office?

Yes, probably, Timothy Naftali told me, but there’s a catch. Naftali, a historian at NYU, was the director of the Nixon Library from 2006 to 2011. Trump won’t likely leave behind a trove as rich as Nixon did, he said, because nobody has.

Posterity, Naftali explained, benefited from unreproducible circumstances in Nixon’s case:

1) Nixon kept meticulous records (including those famous audiotapes) because he was a dedicated student of history. Trump is not.

2) Nixon presumed, mistakenly, that he could weed appalling things out of the official record because the law gave him ownership and control over his presidential records.

What Nixon couldn’t know was that a series of court decisions and legislative changes in response to Watergate would change the existing rules. In essence, the government decided that presidential records were the property not of ex-presidents, as they’d always been judged before, but of the public. Henceforth, they would be controlled, with certain allowances for personal correspondence, by the National Archives. Every president since Nixon has been mindful, as Nixon was not, that posterity was listening in. Though it’s hard to imagine right now, there will one day be a Trump Library, and it will be administered not by Trump and his descendants but by the National Archives.

Trump’s presumed understanding of the way the game is now played doesn’t mean we won’t have some capacity to eavesdrop on his administration. In recent years, voice-recognition software has made it easier to create near-verbatim transcripts of “memcons,” or memorandums of presidential telephone conversations made by duty officers in the Situation Room. It was a memcon of Trump’s July 2019 conversation with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky about investigating Hunter Biden (“I would like you to do us a favor though”) that led to his impeachment.

Eventually we’ll get to see other Trump memcons, though their release will likely be slowed by national-security claims. With some luck we’ll also get to see raw transcripts produced by the voice-recognition software. But those won’t be equivalent to the transcripts of the Nixon tapes, because the voice recognition captures not the president’s voice but that of the duty officer repeating what he’s just heard. Besides, a former staffer on the National Security Council told The Washington Post in September 2019 that Trump’s political appointees on the NSC, departing from previous practice, routinely edited out glaringly erroneous or offensive things that the president blurted out in conversations with foreign leaders.

Access to the documentary record will be limited by other considerations too. Under the 1978 Presidential Records Act, the National Archives may not grant the public access to presidential documents for a period of five years. Ex-presidents are given considerable latitude—too much, really—to restrict access to certain types of records, including those related to national-security and medical matters. This means that it may be a while before we find out what prompted Trump’s unexplained Saturday-afternoon visit to the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in November 2019. (The White House said it was part of his “routine annual physical exam,” an explanation that the press immediately concluded was a lie.)

Another difficulty will be Trump’s habit, acquired when he was in real estate, of ripping up documents. At least in theory, this is against the law. For a while, Politico reported, Solomon Larty and Reginald Young Jr., two career White House records-management officials, literally gathered wastepaper from the Oval Office and the presidential residence and Scotch-taped the ripped-up documents back together. But in the spring of 2018, they were fired abruptly and marched off the White House grounds by Secret Service agents. We don’t know whether any Scotch-taping continued after that.

“It’s very hard,” Naftali noted drily, “to make available a record that doesn’t exist anymore.”

Posterity does have a few arrows in its quiver, though.

The mountain of documents produced by the White House (not to mention the other executive agencies) is so great that they can’t all be doctored or ripped up. Keep in mind that at least some people working in the White House take their legal duties seriously, or are angry at Trump for not protecting them against exposure to COVID-19, or just don’t like the guy, because he treats them like scullery maids. (“He’s never cared about us,” one Secret Service official reportedly said about Trump.)

Another point in posterity’s favor is that Trump, for all his talk about loyalty, has never commanded much from the people who work for him. No visible bonds of affection or respect bind Trump to his employees, leaving fear the sole motivation for keeping the troops in line. (See Cohen, Michael.) Most of that fear will evaporate by January 20, by which time trade publishers may be turning away proposals for tell-all books lest they create a market glut. Unlike the previous two administrations, which were somewhat difficult for reporters to penetrate, the Trump White House leaked like a sieve. Après lui, le déluge.

One variable that previous administrations didn’t contend with is the nondisclosure agreements that Trump handed out like so much penny candy. Trump has always been a maniac about enforcing his NDAs. He even sued his ex-wife Ivana Trump for violating an NDA in their divorce agreement by publishing a work of fiction (a bodice ripper titled For Love Alone that was later turned into a TV movie). The case settled out of court. It may give pause to some signatories that this president is a billionaire (or at least a multimillionaire) who uses drawn-out litigation to bleed his enemies dry. But Benjamin Wittes, the editor in chief of Lawfare, says he expects that plenty of ambitious young lawyers will be willing to harvest favorable publicity by representing on contingency or pro bono the many Davids forced into battle with the Trump Goliath. “I think there will be a cottage industry,” he told me.

The outstanding questions are too many to count.

How close did we come to war with North Korea when Trump threatened to rain “fire and fury” on Kim Jong Un? After Trump decided instead to become the first president to meet with Kim, how close did Trump come to agreeing to remove U.S. troops from the Korean peninsula?

Exactly how much revenue did Trump properties collect from the federal government during his presidency? How much from people seeking to influence Trump’s presidency?

Who has received promises from Trump that they’ll be pardoned? Did Trump promise in advance to commute Roger Stone’s sentence?

What were the domestic arrangements in the Trump White House? Can Melania and Barron really be said to have lived there, or did they spend more time in their New York apartment, or at her parents’ house in Maryland, where Barron went to school?

Did White House aides observe signs of mental decline in Trump related to aging?

Precisely how much money does Trump owe, and how much of it is owed to people or banks linked to Vladimir Putin?

Which companies did Trump steer business to, and did he violate any laws in doing so?

What did Trump say in private about specific white-supremacist groups that supported him?

What private agreements existed between Trump and his attorney general, William Barr, to advance Trump’s political interests?

How serious was Trump about trying to buy Greenland?

We may not learn the answers to all these questions. But we’ll likely learn a lot more than we know now. The only downside is that this will require devoting more of our attention to Donald Trump—something few of us may have the stomach for just now.