The obsolete noun quoz denoted an odd or ridiculous person or thing. It is first recorded in The Festival of Momus, a Collection of Comic Songs, Including the Modern and a Variety of Originals (London, 1780?).

The 1789 text entitled Quoz, a New Song (quoted below) seems to indicate that quoz was merely a fanciful variant of the noun quiz. Attested in 1780, quiz originally denoted a person whose appearance is peculiar or ridiculous—cf. origin of ‘quiz’ (“Vir bonus est quis?”)?.

In the following passage from Volume IV of Camilla: Or, A Picture of Youth (London, 1796), by the English author Frances Burney (1752-1840), Clermont Lynmere, an obnoxious student, uses both quoz and quiz when talking to Sir Hugh Tyrold about Mr. Westwyn, a good-hearted old man and a friend of Sir Hugh’s:

“Upon my honour,” cried Lynmere, piqued; “the quoz of the present season are beyond what a man could have hoped to see!”

“Quoz! what’s quoz, nephew?”

“Why, it’s a thing there’s no explaining to you sort of gentlemen; and sometimes we say quiz, my good old sir.”

The following song was published in the poetry section of The New London Magazine; Being an Universal and Complete Monthly Repository of Knowledge, Instruction, and Entertainment (London) of September 1789. This song inventories the fashionable words and phrases that quoz has recently supplanted—among them is quiz (cf. “Jack’s a Quiz; because Jack gives way to Jill, and so does Quiz to Quoz.”):

QUOZ,

A NEW SONG.

Written and sung by Mr. Edwin, at the Theatre-Royal, Haymarket.HEY for such buckish words, for phrases we’ve a passion

Immensely great, and little once, were all the fashion;

Hum’d, and then humbug’d, Twaddle tippy poz;

All have had their day—but now must yield to Quoz.Walk about the town, each time you turn your head, Sir,

Pop, staring in your phiz, is Q, U, O, and Z, Sir:

Cried Madam Dip to deary, its monstrous scandaloz,

To write on people’s shutters that shameful, nasty, Quoz.Once it was the Barber, for ev’ry thing that’s right:

The Shaver knock’d the Barber quickly out of sight.

Now we’ve got a new word, how invented ’twas,

If you ask, I’ll tell—, my answer, Sir, is Quoz.The Hobby Horse, of late, we rode about with speed,

For drinking, wenching, gaming, ’twas the word, indeed;

Then Macaroni, Bore, and Rage, never sure the like was,

Yet all that sort of thing gave way to little cunning Quoz.Tipsy, dizzy, muzzy, sucky, groggy, muddled,

Bosky, blind as Chloe; mops and brooms, and fuddled,

Florid, torrid, horrid; stayboz, hayboz, layboz—

Words with terminations not so good as Quoz.But when Quozzy came, Tippy, Bore, and Twaddle,

Bucks of blust’ring fame, could not keep their saddle:

One attempts to rally—bully Quiz it was;

But by nightly Sally, dubs him little Quoz.There’s a jack to roast your meat, a jack to hold your liquor;

Jack upon the green to amuse the Vicar:

Jacks of various sorts—Jack’s a Quiz; because

Jack gives way to Jill, and so does Quiz to Quoz.Some may think it French, some may call it Latin;

Some give in this meaning, others will give that in:

Mean it what it will, or sense or non compos,

The meaning, I should think—the meaning must be—Quoz.Suppose we say its drinking—suppose it means a dinner—

Suppose a Methodist—suppose a wicked sinner—

To finish my suppose—suppose I make a pause—

I’ve hit it now—’tis thank ye—and so, good people, Quoz.

In the Preface to A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (London, 1785), the English antiquary and lexicographer Francis Grose (1731-91) wrote about the ephemeral nature of the fashionable words, and explained that he had recorded them—the words in bold appear in Quoz, a New Song:

The fashionable words, or favourite expressions of the day, also find their way into our political and theatrical compositions; these, as they generally originate from some trifling event, or temporary circumstance, on falling into disuse, or being superseded by new ones, vanish without leaving a trace behind, such were the late fashionable words, a Bore and a Twaddle, among the great vulgar, Maccaroni [sic] and the Barber, among the small; these too are here carefully registered.

In the same edition of A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, Francis Grose defined several of the words mentioned in Quoz, a New Song:

THE BARBER, or that’s the barber, a ridiculous and unmeaning phrase, in the mouths of the common people about the year 1760, signifying their approbation of any action, measure, or thing.

[…]

BORE, a bore, a tedious troublesome man or woman, one who bores the ears of his hearers with an uninteresting tale, a term much in fashion about the years 1780, and 1781.

[…]

MACCARONI, an Italian paste made of flour and eggs; also a fop, which name arose from a club, called the maccaroni club, instituted by some of the most dressey travelled gentlemen about town, who led the fashions, whence a man foppishly dressed, was supposed a member of that contraction stiled a maccaroni.

In Additions and Corrections, Grose defined another word mentioned in Quoz, a New Song:

Twaddle, perplexity, a confusion, or any thing else, a fashionable term that succeeded a bore.

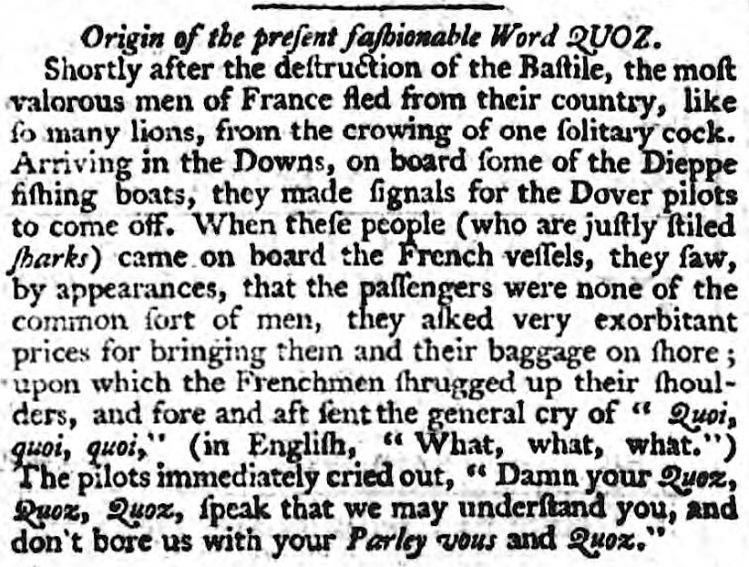

Quoz, a New Song, was followed by this fanciful etymology of quoz in The Bury and Norwich Post; Or, Suffolk, Norfolk, Essex, and Cambridge Advertiser (Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk) of Wednesday 23rd September 1789:

Origin of the present fashionable Word QUOZ.

Shortly after the destruction of the Bastile [sic], the most valorous men of France fled from their country, like so many lions, from the crowing of one solitary cock. Arriving in the Downs, on board some of the Dieppe fishing boats, they made signals for the Dover pilots to come off. When these people (who are justly stiled sharks) came on board the French vessels, they saw, by appearances, that the passengers were none of the common sort of men, they asked very exorbitant prices for bringing them and their baggage on shore; upon which the Frenchmen shrugged their shoulders, and fore and aft sent the general cry of “Quoi, quoi, quoi,” (in English, “What, what, what.”) The pilots immediately cried out, “Damn your Quoz, Quoz, Quoz, speak that we may understand you, and don’t bore us with your Parley vous and Quoz.”

Charles Mackay had a whole paragraph illustrating the usage of “quoz” in Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.

“London is peculiarly fertile in this sort of phrases, which spring up suddenly, no one knows exactly in what spot, and pervade the whole population in a few hours, no one knows how. Many years ago the favourite phrase (for, though but a monosyllable, it was a phrase in itself) was Quoz. This odd word took the fancy of the multitude in an extraordinary degree, and very soon acquired an almost boundless meaning. When vulgar wit wished to mark its incredulity, and raise a laugh at the same time, there was no resource so sure as this popular piece of slang. When a man was asked a favour which he did not choose to grant, he marked his sense of the suitor’s unparalleled presumption by exclaiming Quoz! When a mischievous urchin wished to annoy a passenger, and create mirth for his comrades, he looked him in the face, and cried out Quoz! and the exclamation never failed in its object. When a disputant was desirous of throwing a doubt upon the veracity of his opponent, and getting summarily rid of an argument which he could not overturn, he uttered the word Quoz, with a contemptuous curl of his lip and an impatient shrug of his shoulders. The universal monosyllable conveyed all his meaning, and not only told his opponent that he lied, but that he erred egregiously if he thought that any one was such a nincompoop as to believe him. Every alehouse resounded with Quoz; every street-corner was noisy with it, and every wall for miles around was chalked with it.

“But, like all other earthly things, Quoz had its season, and passed away as suddenly as it arose, never to be the pet and the Idol of the populace.”

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike