I wasn’t really all that familiar with the American Institute of Graphic Arts/AIGA when I got a call in 2000 telling me they’d awarded me what turned out to be my first Lifetime Achievement medal. Honestly, I was a little freaked out, I was still in my 40s. Was this it, was it over? But, I guess given that my biography, written by Bill Burnett is titled “I’ve Lived 5 Lives,” I shouldn’t have been too put off, after all it was only for one of those lives –#3– which was pretty much done. I was already on my way into a couple more.

Of course, along with my slight embarrassment at getting a design award without actually being a designer, I was more than honored. And floored that an esteemed historian and writer, Steven Heller, wrote the appreciation.

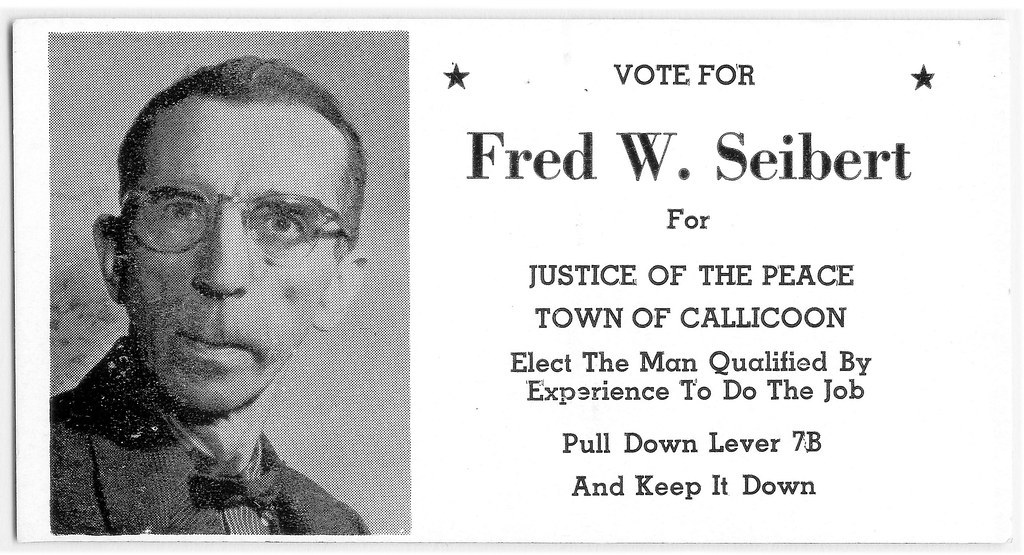

The Instigator: Fred Seibert

By Steven Heller

American Institute of Graphic Arts/AIGA

www.aiga.org

164 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

Fred Seibert’s career proves that it is not necessary to be a Yale/Cranbrook/RISD/SVA educated, AIGA/TypeDirectors/Art Director’s Club-award-winning, bona fide/pedigreed/certified graphic designer, or any other kind of designer, to create the most indelible visual identities for some of the most visible pop culture media in the world. You just have to be a fan. A fervent, ardent, passionate devotee of “people who do fantastic work in music and visual stuff,” as Seibert puts it.

Oh, yeah, you also have to have the vision thing.

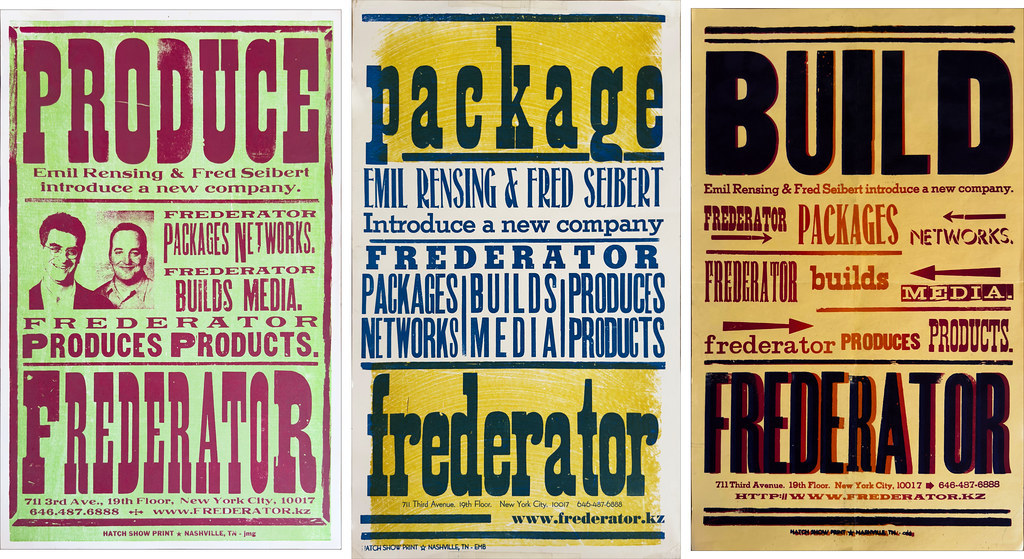

Without vision, and the talent, know-how and ambition to realize it, Seibert might have become a tie-dyed-in-the-wool Dead Head selling pot brownies from the back of a psychedelicized microbus. Instead, he instigated, orchestrated, facilitated and otherwise dreamed-up the nascent visual personas of MTV and Nickelodeon, back when they were truly vanguards of the pop-cultural revolution. In the ensuing years he has exerted a significant influence on the look and content of animated cartoons, first as president of Hanna-Barbera and later as the founder of Frederator, a cartoon production company that provides programming to the Cartoon Network. If these accomplishments were not enough for one lifetime, he has recently become president of both MTV Networks Online and Nickelodeon Online, where he has had a hand in transforming the Internet by provoking, stimulating and triggering numerous creative collisions.

“Seibert may not fit the accepted definition of a graphic designer, but he practices design in the emerging sense of the term, as a producer of ideas,” says Forrest Richardson, a graphic designer and a member of the 1999 AIGA Medal selection committee. “Seibert designs in the broadest sense by enlisting other people who create unprecedented ideas. Just look at what he has spawned.”

What he spawned was a series of environments—at MTV, Nickelodeon, Hanna-Barbera and the Cartoon Network—where creative misfits were able to create unconventional film and animation that otherwise would have had few, if any, outlets. And possessed with a keen ability to see beyond the current thing to the next big thing, and even a few things beyond that, Seibert has a knack for predicting what the public will like, because as a fan he likes it too. In a formal sense, he constructs complex matrices of interconnected concepts designed to support overarching visual communications that project mnemonic identifying images. More simply put, he matches the right person with the best project to get extraordinary results. Moreover, he understands the distinction between integration and interference and rarely asks creative people to slavishly execute his own ideas. “They will do it grudgingly, and expensively,” he explains. Rather, he defines contexts, provides opportunities and encourages individual points of view that are used as components of larger programs. He employs those people—young and old, neophyte and veteran—who can interpret a basic blueprint and transcend its confines. So in addition to being an ersatz designer, Seibert is a full-blown impresario. He is also the proverbial whiz kid, the one who always dreamed of making great things.

“The Beatles proved that you could zig and zag through various polarities and still be the thing that you were,” recalls Seibert, who was born in 1951 and heard the Beatles for the first time when he was 12 years old. He still speaks of that defining moment with breathless enthusiasm. “It was a really inspiring thing for me to know that you could go from Sergeant Pepper’s to the White Album, from ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ to ‘A Day In The Life,’ from Rubber Soul to Let It Be. I also found inspiration in the fact that they were the ultimate 20th century media thing. They wanted to be a beast of the media and appeal to millions and millions and millions of people, and make trillions and trillions and trillions of dollars, but they did not think that that was in any way counter to making art.”

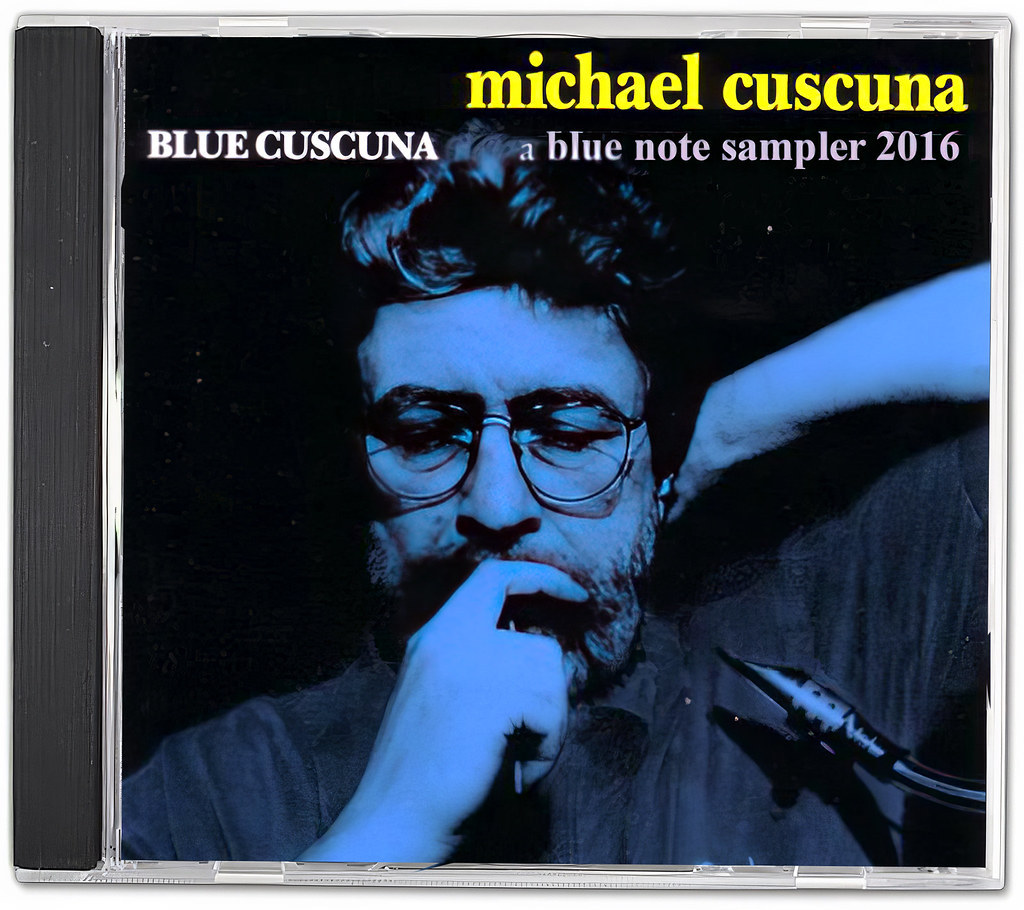

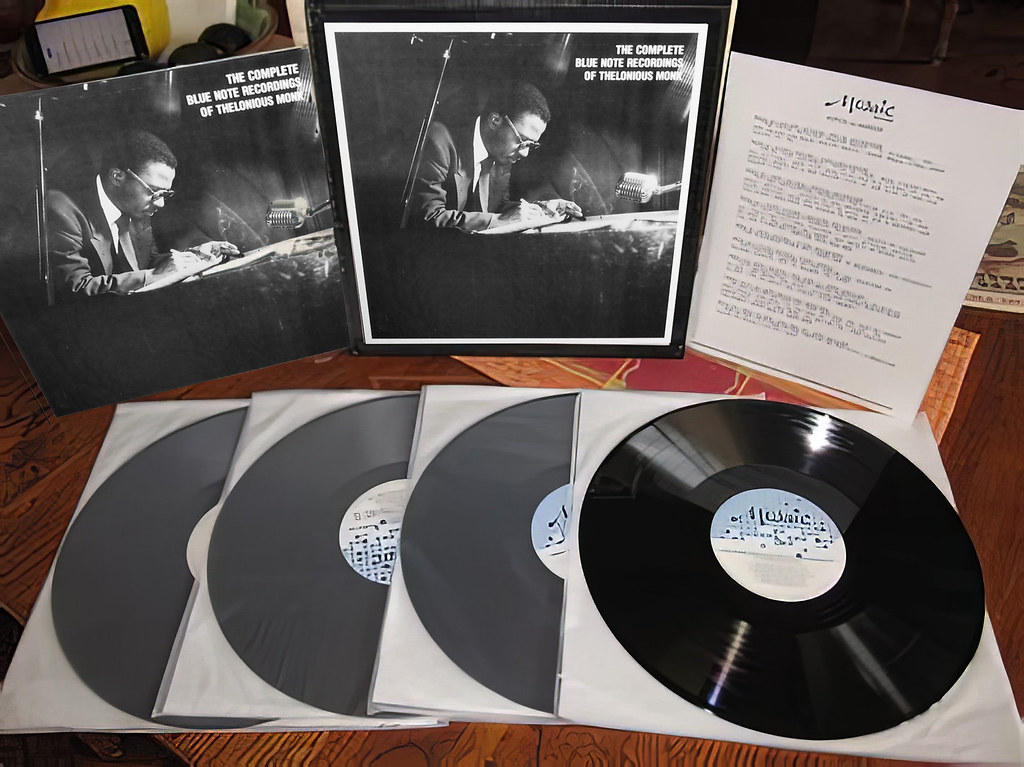

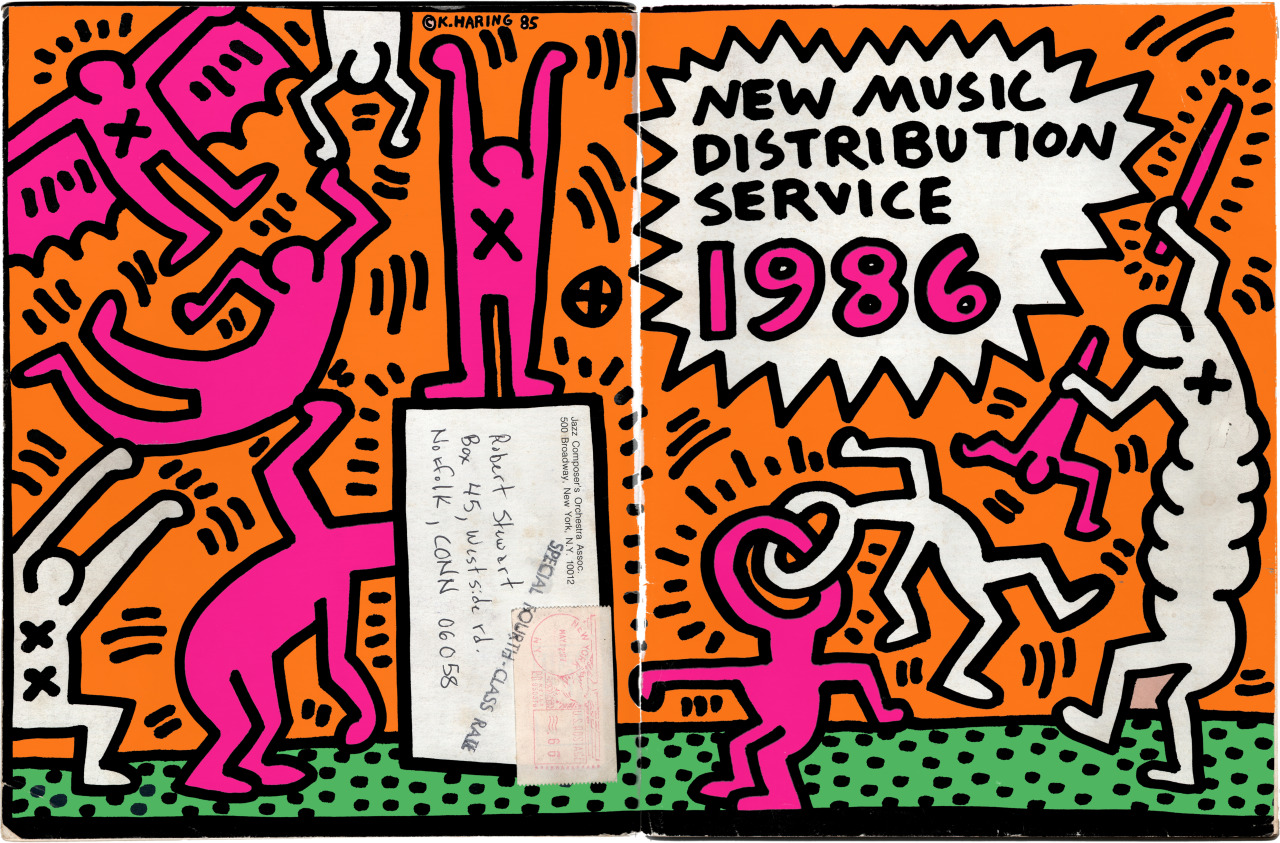

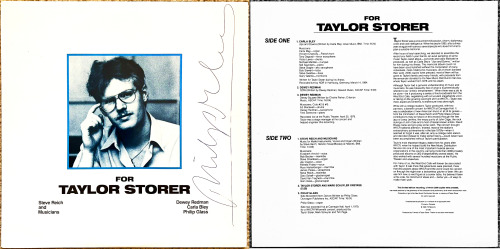

Seibert always wanted to be in the music business. In his early 20s he had a brief stint as a DJ on a college radio station and later produced avant-garde jazz records for a small independent label. Yet he failed to attain his goal of pop record producer because, he laments, “I didn’t smoke enough dope.” At 27, he stumbled into the promotion side of the radio business and was hired by adman Dale Pon, who introduced him to Bob Pittman. Pittman was a 25-year-old radio programmer who had just switched over to the cable TV business to shepherd a new venture: a channel that would show music videos 24 hours a day. Pittman invited Seibert to join him in the venture that would become MTV, and with trepidation he complied. “I watched television, I didn’t make it,” Seibert says about his initial misgivings. And yet all those hours spent in front of the tube had left him with a natural affinity for the medium.

The cable business was so new that virtually anything Seibert tried earned praise. One of his first promos was a kinetic montage of images cut to the beat of claps in the song, “Car Wash.” “They [the bigwigs] thought it was an amazing thing,” he reports. “I guess television didn’t usually do things to the beat.” Virtually unfettered Seibert continued to intuitively brand the emerging channel through quirky spots and bumpers. “In those days we didn’t know the word ‘brand,’ and so we broke many of the rules that had governed television’s identity for decades,” he remembers. Seibert, with his friend and MTV colleague Alan Goodman, used cable TV as a laboratory for a slew of unprecedented animations. The idea was to entertain rather than push sales pitches down the audience’s throats. And in the process, Seibert wanted to unleash the talents of creative people he had always admired.

As a teen, Seibert was inspired by the wellspring of innovative graphic design and packaging that came out of Columbia Records during the ‘60s and early ‘70s. He particularly admired the work of art director John Berg who, he explains, “created a language that reflected the wildly diverse sensibilities of type design, photographic imagery and portraiture of the time. And yet there was this amazing consistency, a quality of ideas that went through the whole thing.” (Inspired by this work, Seibert taught himself to “design” covers for his own company, Oblivion Records, which he founded while working at MTV.) When he launched the promotions for MTV, his model was not Lou Dorfsman’s legendary advertising for CBS Television, which was considered the industry standard, but Berg’s art direction for Columbia. “I wanted the MTV visuals to be like album covers for television,” he says. Seibert began his work at MTV with the idea that since music was multifaceted, the network should avoid projecting a rigid corporate persona or, for that matter, anything corporate looking. The television industry revered the sanctity of logos: the CBS Eye (1951), NBC Peacock (1956) and ABC circle (1961) embodied the networks’ respective ethos and were thus immutable and inviolable. So Seibert’s first instinct was to avoid the I.D. firms that churned out the most expensive corporate identity systems. Instead, he commissioned a childhood friend, Frank Olinsky, who was a principal along with Pat Gorman and Patti Rogoff in Manhattan Design, a very small graphics and illustration office tucked behind a tai chi studio in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village. Although they had no previous corporate identity experience, Seibert chose them “because I’d been friends with Frank since I was four years old, and he was talented even then.” He also loved rock and roll. Luckily, Bob Pittman agreed that the logo could take any form as long as the “call letters” were readable.

The first version of the “M” was inspired when Patti Rogoff walked past a graffiti-scrawled schoolyard wall. At that moment she realized MTV’s logo had to be made of three-dimensional letters that exuded street culture. After many false starts, Pat Gorman finessed a large M and hand-scrawled a little “TV” onto it, which Olinsky thought was ugly. He argued that if the concept was going to work, a better rendering of “TV” was imperative. But their real breakthrough came when Gorman and Olinsky decided that the M could be something like a screen on which various images could be “projected.” And the M could become an object—a birthday cake, or a bologna sandwich or whatever else they wanted to make it. The shape of the M could be transformed into anything, as long as it continued to look like an M. Back at headquarters, MTV executives were troubled by the solution. They felt that the M was not legible. And their lawyers argued that a mutable logo would require repeated registration each time a different iteration was used. Seibert, however, was not concerned. Five variations of the logo were pinned up on his wall for weeks because he couldn’t make up his mind which one he liked best. Finally, he decided it would be “very rock and roll” to use them all in animated sequences. It seemed like the problem was solved.

Still, the head of sales lobbied to kill the logo because he didn’t want to send such a flagrantly unconventional design to potential advertising buyers. Seibert recalls that he was asked by the muckety-mucks if he really thought that this logo would last as long as the CBS Eye. His answer was a resounding “No.” “Why would I think that a rock thing would stand up to the icon of TV logos?” The executives insisted that Seibert approach some “real” designers, including Push Pin Studios and Lou Dorfsman, which he did. But Seibert kept total faith in the original idea and slyly admits, “I sandbagged the assignment. They all did terrible work and then we were out of time.” So with a small type variation on the “Music Television” subtitle, the original was approved a few weeks before the new channel went on the air, on August 1, 1981.

The televised MTV logo was the perfect embodiment both of raucous rock and roll and of MTV’s promise to change forever ordinary viewing (and listening) habits. Its animated mutability made it as anticipated a feature of daily programming as the music videos themselves. Over time various illustrators were hired, including John van Hammersveld, Mark Marek, Lynda Barry and Steven Guarnaccia, to transform the basic prop into mini-metaphors. But the most important vehicle for establishing the logo’s supremacy were 25 10-second animated spots in which the logo changed design and meaning. This included the most recurring and iconic spot, an appropriation of the famous photograph of the first man landing on moon with a vibrating, ever-changing MTV logo used in place of the American flag. “Ultimately,” recalls Seibert, “we did three or four hundred promos that were the real heartbeat of the ‘newness’ of MTV.”

Four years after MTV launched, Seibert and Alan Goodman helped restructure a foundering Nickelodeon, transforming it from a repository of stale cartoons to a content-driven destination of original entertainment for young and old. Unlike network TV, where programming aims for high ratings at all costs (by filling the air with trendy action heroes or “When Pets Attack”), Nickelodeon was determined to do things right, with stories and characters that were good from a kid’s point of view. “If we did that well, then we’d make money,” says Seibert. Within a year, the channel’s ratings had made a huge jump. The duo also devised Nick-at-Nite, a brilliant scheme to broadcast reruns of baby-boom TV classics during the time slots when younger kids were in bed. For Seibert this was more than a retrogimmick, it was a move to philosophically position the channel as a repository of great pop culture. “Back then, old television was considered even more disposable than old music,” he explains, “and I was determined to prove—even to Gerry Laybourne who ran Nickelodeon—that it wasn’t junk, that it has cultural value.”

Which is the reason why after leaving MTV and Nickelodeon he accepted the top job at Hanna-Barbera, the cartoon studio known for its pioneering “limited animation” style, yet which for decades had been churning out mediocre reprises of their cartoon classics, which included “The Flintstones,” “The Jetsons,” “Yogi Bear,” and others. Seibert’s understood that with the success of Matt Groening’s “The Simpsons” and John Kricfalusi’s “Ren and Stimpy,” a new generation of cartoon creators was waiting to be tapped. He immediately altered the archaic internal organization of Hanna-Barbera, which emphasized production over concept and technicians over artists. His model was based on creative teams that enabled new ideas to take precedence over old chestnuts. He soon oversaw the creation of HB’s first new series in decades, “Two Stupid Dogs.” The cartoon did not do well, yet out of this failure he devised a unique concept called “What A Cartoon.” Instead of investing a lot of money in one 13-show series, he used the same capital to produce 48 speculative cartoons, each made by one artist and a team of production people. “What A Cartoon” was an anthology of speculations, and the most successful ones were spun-off into series, later produced by Frederator. The successes included such current hits as “Dexter’s Laboratory,” “The Powerpuff Girls,” “Cow and Chicken,” and “Johnny Bravo.”

Seibert is a product of 1960s mass media, and he admits to a somewhat schizophrenic relationship with the branding that he has done so well. “I am deeply cynical about the goals of branding, which to me, in its purest form, means higher CPMs [cost-per-thousand] for advertising. But I realize that the values that I am looking to change through the work that I do ultimately give value to advertising. That’s the cynical side.” The other side of the relationship is more deeply rooted: “I feel like a ‘60s child, always attracted to things that were disenfranchising to me,” he says. And this is what comes through in the music, cartoons and comics he has fervently tried to integrate into today’s mainstream. “I was very resentful of the fact that in the ‘60s people said that the music I liked was ‘disposable.’ It definitely wasn’t disposable to me. So one of the things in the back of my mind in the work I was doing at MTV was, ‘I’ll make them listen!’ and give this stuff new value.”

MTV and Nickelodeon are wildly successful today. And given the current reach of cable and satellite TV, their identities may be more recognized internationally than all the networks combined. Irreverent, oddball and sometimes-gross cartoons also fill television now more than ever. Seibert must be given credit for a fair share of this.

Yet Seibert’s chronic restlessness prevents him from basking too long in the glow of previous accomplishments. For the past three years he has been working in the newest mass medium, as a player in the Internet. After his stint at Hanna-Barbera, he became president of MTV Networks Online, a position he now holds at Nickelodeon Online. He confides that “I don’t have a bottom of my toes feeling yet” about the new media. Yet complete mastery of a medium has never been a handicap for him before. Rather, his unflagging enthusiasm for the creative potential of the medium is what makes him invaluable. “What I do with the Internet is find unbelievably talented people, the way I always have, put them in a room where the best ideas can come out, then defend their right to have ideas and fail or succeed.” As a fan, he adds, “I follow these great people and I’ve found myself attracted to places where great people are attracted. I figured that by the rub-off of their greatness, I could feel better.” Seibert’s modesty is not false. His exposure to a legion of creative people who have worked for him has definitely enriched his life. But in the final analysis, because Seibert has spent his career instigating creative people, the media, popular culture and the mass audience has been greatly enriched, too.

Steven Heller, art director of the New York Times Book Review, is the founder and co-chair of the School of Visual Arts MFA/Design program. He is the author of over 70 books on graphic design and popular art, including Paul Rand (Phaidon), Typology: Type Design from the Victorian Era To The Digital Age (Chronicle Books), Letterforms: Bawdy Bad and Beautiful (Watson Guptill), Design Literacy, Design Dialogues, Sex Appeal: The Art of Allure in Graphic Design and Advertising Art and The Swastika: Symbol Beyond Redemption (all Allworth Press).

![Next New Networks [posters]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/cea61f9e07af0d25cd99929a95c684c6/20d1d856996a2a97-da/s1280x1920/005d627531cc109451c2f2f0696d247847c83add.jpg)

![Channel Frederator [McDonald's] postcard](https://64.media.tumblr.com/e2c63dec7aa1377918b8efd6aedffaf8/448dc63e0e9b7393-1a/s500x750/1b440e76f4f8e02d513da0dd18286de4717dd7dc.jpg)