I don’t know if Alan Moore was the first artist who I really thought of as an artist. But Moore, who announced his retirement from making comic books this week, was the first person on the strength of whose name I was willing to pay more money than I should have.

Way back in the mid-1980s, I was in high school and Moore, with artists John Totleben and Steve Bissette, were in the middle of their classic run on Swamp Thing. My younger brother and I had come on board about halfway through, and were trying to collect all the back issues. Our local comics shop – a stereotypically seedy establishment that would go out of business a couple years later after failing to pay sales tax – had a copy of the first famous issue of Moore’s run, The Anatomy Lesson. It was $20 – which seemed a fortune for us at the time. We’d come into the store and stare at it, week after week, with a not un-Moore-like mixture of longing, despair and desperation. There was no trade graphic novel collection of Moore’s run, yet, as far as we knew pre-internet, so if we wanted to read the story, this was pretty much our only option.

Finally, we broke down, gathered up our allowance, and bought the comic (sans sales tax). And, amazingly, it was worth it.

“It’s raining in Washington tonight,” the villain Jason Woodrue, the Floronic Man, muses on the first page. He segues into a brief ode to all the people in their apartments taking their houseplants outside to the fire escapes, “as if they were infirm relatives or boy kings. I like that”, he adds – and I liked it too. I’d never thought of watering plants as a kind of leafy fealty. Thirty years later, I still think about that line when I see plants on window sills; it will probably be with me till I die.

Superhero comics are supposed to show you monsters hitting each other; they’re not supposed to change the way you look at the world. Part of what was exhilarating about those first Swamp Thing comics was the way that Moore and his collaborators so gleefully ignored the boundaries of their genre and medium. The Anatomy Lesson famously inverted Swamp Thing’s origin – he was no longer a man who had turned into a monster, but a mass of plants which had been fooled into thinking it was a man. But the issue also vivisected superhero comics, and made them into something else. Even Bissette and Totleben’s rendering of the title puts the reader on notice; The Anatomy Lesson is written in bulbous, but still gracefully curved script upon the torso of a human figure, arms and legs and head cut off on a dissecting table. The striking stylization is more constructivist movie poster than mainstream comic. It’s a design that insists on being recognized as design. Here, it says, in this unlikely place under the superhero narrative, is art.

You can see that same ambition in a new collection of Moore’s short stories, Brighter Than You Think, edited by comics scholar Marc Sobel. The 10 selections cover a sizable swathe of Moore’s career from a 1985 sci-fi throwaway to a 2003 biography of rocket scientist and mystic John Whiteside Parsons, which got censored by DC comics because of references to Scientology. In each story, you can see Moore poking, prodding and simply ignoring the boundaries of pulp comics storytelling. The one superhero story, In Pictopia, with artist Donald Simpson, is a bleak elegy to comics past; the most vivid image is of a group of X-Men-like characters torturing Disney’s Goofy and snickering. Another story is a critique of post 9/11 clash of civilizations rhetoric. The range of collaborators is perhaps even more dazzling; Peter Bagge’s rubbery degenerates slouch around Moore’s sad tale of the pitcher-headed Kool-Aid mascot who wanted to be a beat poet, while a story about Japanese executives and competitive bowing is rendered in Mark Beyer’s simplified nightmare children’s book designs.

I wouldn’t say that I love all – or even any – of the short stories collected here. Bill Wray’s plastic, expressionist art gives Come On Down a satiric nightmare feel somewhere between Mad magazine and Munch, but Moore’s story of a gameshow where the prize is suicide is a bit too pat to live up to the visuals. The much-lauded history of homosexuality, The Mirror of Love, was bold for a mainstream comics artist in 1987, but in retrospect it comes across as both obvious and lugubrious, without either the passion, the insight, or the artistry of David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger and Marguerite Van Cook’s 70 Miles a Second.

Quick GuideThe five Alan Moore comics you must read

Show

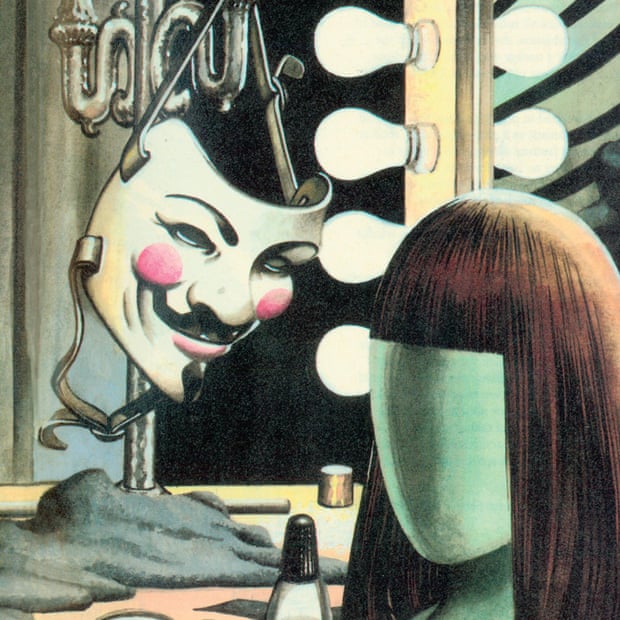

V for Vendetta (1982 - 1989)

This dystopian graphic novel continues to be relevant even 30 years after it ended. With its warnings against fascism, white supremacy and the horrors of a police state, V for Vendetta follows one woman and a revolutionary anarchist on a campaign to challenge and change the world.

Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow (1986)

Moore's quintessential Superman story. Though it has not aged as well as some of his work, this comic is still one of the best Man of Steel stories ever written, and one of the most memorable comics in DC's canon.

A Small Killing (1991)

This introspective, stream-of-consciousness comic follows a successful ad man who begins to have a midlife crisis after realising the moral failings of his life and work.

Tom Strong (1999 - 2006)

A love letter to the silver age of comics that nods to Buck Rogers and other classics of pulp fiction. Tom Strong embodies all of the ideals Moore holds for what a superhero should be.

The League of Extraordinary Gentleman (1999-2019)

One of Moore's best known comic series, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is the ultimate in crossover works, drawing on characters from all across the literary world who are on a mission to save it.

For that matter, over the years, my enthusiasm for many of Moore’s major works has faded; I still love Watchmen and From Hell, and for that matter Swamp Thing. But V for Vendetta is far too enamored of the awesome superiority of its protagonist, while Promethea is too enamored of Moore’s crank mystical insights.

But the fact that Moore frequently fails is part of what I still love, and find inspiring, about his work. Though he first achieved fame as a work-for-hire hack writing corporate properties, Moore always insisted on seeing himself as an artist – someone willing to try new subjects, experiment with new forms, work with new people, and, not infrequently, stumble in new ways. Brighter Than You Think is uneven, but the unevenness is itself a kind of triumph. Moore’s genius is that he’s always been eager to cut himself apart and put himself back together. And if occasionally the results are a muck-encrusted mockery of art, you just have to take out that dissection knife, and try again.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion