イスタンブール

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2024/04/01 04:10 UTC 版)

歴史

21世紀初めに考古学者により発見された紀元前7000年に遡る新石器時代の遺物は、イスタンブールの歴史的な半島には以前考えられていたよりも前のボスポラス海峡が形成される以前から人が住んでいたことを示している[54]。 遺物の発見以前はフリギア人を含めトラキア人の部族がサイライブルヌに紀元前6000年後半から住み始めたと言うのが従来の考えである[25]。アジア側の遺物は紀元前4000年に遡る物とされ、カディキョイ地区のフィキルテペ Fikirtepe で発見されている[55]。同じ場所は紀元前1000年初めにはフェニキアの交易地点で、同様に紀元前660年頃に設立されたカルケドンの町があった[注釈 2]。

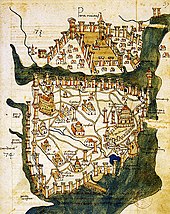

しかしながら、イスタンブールの歴史は一般的に紀元前660年頃[注釈 2]にビザス王の下メガラからの入植者が、ボスポラス海峡のヨーロッパ側に植民都市ビザンティオンを創建した時代に遡る。入植者は金角湾に隣接した初期のトラキア人の居住地であった場所にアクロポリスの建設を進め、生まれたばかりの都市の経済に勢いを与えた[56]。ビザンティオンは紀元前5世紀の変わり目に短期間アケメネス朝の支配を経験するが、ギリシャ人はペルシア戦争で取り戻している[57]。都市の開祖はギリシア神話の海神ポセイドンとケロエッサの間に生まれた子ビザスであり、彼は太陽神アポロンの協力を得て彼の名を冠した「ビュザンティオン」を建設したとされ、トラキア人の王による侵略から町を守り、妻ペイダレイアもスキタイの侵攻を防いだとも言われる[6]。ビザンティオンは デロス同盟とその後の第二アテナイ連合の一部であったが、紀元前355年についには独立を得ている[58]。長いローマとの同盟関係の後、ビザンティオンは73年に公式にローマ帝国の一部となった[59]。ビザンティオンのローマ皇帝セプティミウス・セウェルスに対抗する敵対者 (en) ペスケンニウス・ニゲルの支持は大きな代償となり、2年にわたる包囲は都市を荒廃させた。195年に降伏している[60]。

それにもかかわらず、セウェルスは5年後にビザンティオンの再建を始め都市は回復し多くの取引はそれ以前の繁栄を上回った[61]。

コンスタンティノープルの興亡

コンスタンティヌス1世は324年9月に実質的なローマ帝国全体の皇帝になった[62]。コンスタンティヌスは2ヶ月後に新しいキリスト教の都市にビザンティオンを置き換えるための都市計画を打ち出した。帝国の東の首都として都市は新ローマを意味するネア・ローマNea Roma と名付けられたが、一番単純なコンスタンティノープルの名称が20世紀まで続いた[63]。6年後の330年5月11日にコンスタンティノープルはついにビザンティン帝国や東ローマ帝国の名称で知られる帝国の首都として宣言された[64]。

この遷都にはいくつかの伝説があり、当初コンスタンティヌス1世はトロイに遷都しようと考えていたが夢で神の啓示を受けて変更した、カルケドンを予定し建設工事に取り掛かったが鷲が道具を咥えてビュザンティオンに飛び去った、また夢に現れた老婆が美しい女性に変貌し、このように古い町ビュザンティオンを新生するよう求められたという[65]。また新都の城壁建設にも伝説があり、コンスタンティヌスが自ら槍を手に地面に線を引いて城壁の位置を指示したが、余りにも長く続くので従者が聞くと、コンスタンティヌスは「私の前を歩く御方がお止まりになるまでだ」と答えたという[65]。

コンスタンティノープルの創建はコンスタンティヌスの最も永続的な成果として、ローマの力の東進や街をギリシャ文化やキリスト教の中心にしたことにある[64][66]。多くの教会が街中に建てられ、その中にはアヤソフィアも含まれ、1000年の間世界最大の大聖堂であり続けた[67]。 コンスタンティヌスにより着手された他の街の改良にはコンスタンティノープル競馬場の大改修や拡張が含まれ、何万もの観衆を収容し競馬場は市民生活の中心となり、5世紀や6世紀にはニカの乱を含め社会不安の出来事の中心であった[68][69]。

コンスタンティノープルの位置はまたその存在が時の試練に耐えることを確実とした。多くの世紀、城壁や海岸により東やイスラムの進軍する侵略者からヨーロッパを守っていた[66]。中世の大部分の間とビザンティン時代の後半、コンスタンティノープルはヨーロッパ大陸最大で最も裕福な都市で、当時の世界最大の都市であった[70][71]。 第4回十字軍の後、コンスタンティノープルの衰退が始まり第4回十字軍の間に略奪や占領があった[72]。コンスタンティノープルは後に正教会のビザンティン帝国を置き換えるために、カトリックの十字軍によって作られたラテン帝国の中心となった[73]。しかしながら、ラテン帝国は短命でビザンティン帝国は弱体化しながらも1261年に復活した[74]。コンスタンティノープルの教会や防衛力、基本的な公益事業は荒廃しており[75]、人口は8世紀の50万人から10万人へ減少していた[注釈 4]。

アンドロニコス2世によって始められた様々な経済や軍事力の削減などの軍事の政策は、帝国を弱体化させ攻撃に対してより脆弱なままにした[76]。

14世紀半ばオスマン朝 (en) は小さな町や都市を攻略し、コンスタンティノープルへの供給路を断ちゆっくりと締め付ける戦略を始めた[77]。1453年5月29日に8週間にわたる包囲の後、ついにスルターンのメフメト2世はコンスタンティノープルの陥落[78]の勝者になりオスマン帝国の新しい首都として宣言された。この間、ビザンティン帝国最後の皇帝であったコンスタンティノス11世パレオロゴスは殺されている。その後、スルターンはアヤソフィアへ赴きイマームにシャハーダを命じ、壮大な大聖堂は帝国のモスクへと変わった[79]。(トルコやイスラム世界では「イスタンブールの開拓」または「イスタンブールの征服」İstanbul'un Fethi と呼ばれている。)預言者ムハンマドのハディース(言葉)で「コンスタンティンの町」を征服する司令官やその兵士たちが褒められているという伝説があり、歴代のイスラム教司令官がイスタンブールの征服を試みた。674年から678年に、ウマイヤ朝初代のカリフ、ムアーウィヤ時代から[80]1453年にオスマン帝国のメフメト2世までの間、イスラム教司令官により計15回の包囲が行われた。1453年にこの町を征服したオスマン帝国のメフメト2世はただちにエディルネから遷都し、イスタンブールは引き続き東地中海を支配する帝国の首都となった。

オスマン朝の時代

コンスタンティノープルの陥落後、メフメト2世は直ちに街を復興するために試みた。モスクと病院、学校などを組み合わせた複合施設群を設立し、ローマ帝国の引いた水道(ローマ水道)を補修し、後のグランドバザールの前身となる屋根付きバザールを始めとする商業施設を建設して都市インフラを再興した。また、王宮としてトプカプ宮殿の建造を開始している[81]。この宮殿はその後も歴代スルタンによって増築が進められ、19世紀半ばまで王宮として帝国政治の中心となっていた。包囲の間都市から逃れていた人々の帰還を促し、ユダヤ教徒や被征服者のキリスト教徒にズィンミー(公認された異教徒)として一定程度の人権を保障して新都にそのまま住まわせる一方、アナトリア半島の諸都市からムスリム(イスラム教徒)の富裕者を強制的に移住させる政策をとったため、15世紀後半の50年間にイスタンブールは東ローマ帝国の末期には激減していた人口を大きく上回る大都市となった。また、スルターンはヨーロッパ中から首都に人々を招き入れ、オスマン期に持続した国際的な社会を築いている[82]。

オスマン朝は急速に街をキリスト教の牙城からイスラーム文化の象徴に変化させた。ワクフは壮大な帝国のモスク、また度々隣接した学校や病院、ハンマムなどの公衆浴場の建設などに資金を供給するため設立された[81]。各街区には君主や大臣などの有力者が設立したモスクが造られ、イスラム都市の伝統に則ったモスクと公共施設が整備された。また、イスラム教徒による差別と抑圧はあったものの東方正教やアルメニア使徒教会の教会、ユダヤ教のシナゴーグも数多く維持され、ムスリムのトルコ人のみならず、ギリシャ人、アルメニア人、ユダヤ人、そして西ヨーロッパ諸国からやってきた商人・使節など、様々な人々が住む多文化都市、東西交易の中心都市でもあった。1517年にオスマン家はイスラム帝国の地位を宣言し、イスタンブールは4世紀にわたりオスマンのカリフの首都として続いた[11]。 1520-1566年のスレイマン1世の治世の時代、特に偉大な芸術と建築的偉業の時代であった。主要な建築家であったミマール・スィナンは市内のいくつかの象徴的な建築物に携わり、この間オスマンの芸術や陶器、イスラームの書法、オスマンの細密画が栄えた[83]。イスタンブールの全人口は18世紀までに57万人に達した[84]。19世紀初めの反乱の時代は進歩的な皇帝であったマフムト2世の高まりに導かれ、政治改革が生じ新しい技術の街への導入が認められ[85]この時代に金角湾に橋が架けられた[86]。1880年代にイスタンブールはヨーロッパの鉄道網と結ばれ[87]、1883年に運行を開始したオリエント急行は、スエズ運河の自由航行に関する条約が締結された1888年にイスタンブールへの直接乗り入れを開始している。これにより、西ヨーロッパとイスタンブールは直接結ばれることとなった[88]。近代的な水道・電気・電話・路面電車などが、オスマン債務管理局を通した公共事業により導入されていった[89]。

20世紀以降から現代

20世紀初め、青年トルコ人革命により廃位されたアブデュルハミト2世や一連の戦争は病んでいる帝国の首都を悩ませた[90]。これらの第一次世界大戦の終わりはイギリスやフランス、イタリアによるコンスタンティノープルの占領の結果となった。遂にはオスマン帝国最後の皇帝であったメフメト6世が1922年11月に亡命し、翌年ローザンヌ条約によりコンスタンティノープルの占領は終わり、アンカラのトルコ大国民議会でムスタファ・ケマル・アタテュルクはトルコ共和国の建国を宣言し[91]共和国が認められた[92]。共和国の初期の頃、オスマンの歴史から新しい世俗的な国を遠ざけるためイスタンブールはトルコの首都の選択から外されアンカラが支持された[93]。しかしながら、1940年代後半から1950年代初めにイスタンブールは大きな構造変化を経験し、新しい公共広場や大通り、道路が市内中で建設され、時には歴史的な建築物が犠牲となった[94]。アナトリアの人々が膨張するイスタンブールの郊外に建設された新しい工場の雇用を見付けるため市内に移住したため、1970年代に急増が始まった。都市のこの突然の人口の増大は大規模な住宅開発の需要の要因となり、以前の中心部から離れた村や森はイスタンブールの大都市圏に飲み込まれた[95]。

1984年に大都市自治体として指定され[96]、2004年の指定範囲拡大により指定区域はイスタンブール県全県となっている[97]。

2016年にはテロが2件発生した(1月の自爆テロと12月の爆弾テロ事件)ほか、2022年11月13日には爆弾テロ事件が発生した[98]。

注釈

- ^ a b c Sources have provided conflicting figures on the area of Istanbul. The most authoritative source on this figure ought to be the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (MMI), but the English version of its website suggests a few figures for this area. One page states that "Each MM is sub-divided into District Municipalities ("DM") of which there are 27 in Istanbul" [emphasis added] with a total area of 1,538.9 square kilometers (594.2 sq mi).[99] However, the Municipal History page appears to be the most explicit and most updated, saying that in 2004, "Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality's jurisdiction was enlarged to cover all the area within the provincial limits". It also states a 2008 law merged the Eminönü district into the Fatih district (a point that is not reflected in the previous source) and increased the number of districts in Istanbul to thirty-nine.[100] That total area, as corroborated on the Turkish version of the MMI website,[101] and a recently updated Jurisdiction page on the English site[102] is 5,343 square kilometers (2,063 sq mi).

- ^ a b c The foundation of Byzantion (Byzantium) is sometimes, especially in encyclopedic or other tertiary sources, placed firmly in 667 BC. However, historians have disputed the precise year the city was founded. Commonly cited is the work of 5th-century-BC historian Herodotus, which says the city was founded seventeen years after the city of Chalcedon,[21] which came into existence around 685 BC. However, Eusebius, while concurring with 685 BC as the year Chalcedon was founded, places Byzantion's establishment in 659 BC.[22] Among more modern historians, Carl Roebuck proposed the 640s BC[23] while others have suggested even later. Further, the foundation date of Chalcedon is itself subject to some debate; while many sources place it in 685 BC,[24] others put it in 675 BC[25] or even 639 BC (with Byzantion's establishment placed in 619 BC).[22] As such, some sources have opted to refer to Byzantium's foundation as simply located in the 7th century BC.

- ^ カザフスタンの首都アスタナも同源である。

- ^ a b Historians disagree—sometimes substantially—on population figures of Istanbul (Constantinople), and other world cities, prior to the 20th century. However, Chandler 1987, pp. 463–505, a follow-up to Chandler & Fox 1974,[84] performs a comprehensive look at different sources' estimates and chooses the most likely based on historical conditions; it, therefore, is the source of most population figures between 100 and 1914. The ranges of values between 500 and 1000 are due to Morris 2010, which also does a comprehensive analysis of sources, including Chandler (1987); Morris notes that many of Chandler's estimates during that time seem too large for the city's size, and presents alternative, smaller estimates. Chandler disagrees with Turan 2010 on the population of the city in the mid-1920s (with the former suggesting 817,000 in 1925), but Turan, p. 224, is, nevertheless, used as the source of population figures between 1924 and 2005. Turan's figures, as well as the 2010 figure,[161] come from the Turkish Statistical Institute. The drastic increase in population between 1980 and 1985 is largely due to an enlargement of the city's limits (see the Administration section). Explanations for population changes in pre-Republic times can be inferred from the History section.

- ^ The United Nations defines an urban agglomeration as "the population contained within the contours of a contiguous territory inhabited at urban density levels without regard to administrative boundaries". The agglomeration "usually incorporates the population in a city or town plus that in the suburban areas lying outside of, but being adjacent to, the city boundaries".[164] Figures dated 1 July 2011 place the populations of the agglomerations of Moscow and Istanbul at 11.62 million and 11.25 million, respectively.[165] The UN estimates that the agglomeration of Istanbul will exceed the agglomeration of Moscow in population by 2015 (with 12.46 million and 12.14 million, respectively), although extrapolation suggests that the former will not surpass latter until the second half of 2013. A revision with 2013 data is due in the first half of 2014.[164]

- ^ While UEFA does not apparently keep a list of Category 4 stadiums, regulations stipulate that only these elite stadiums are eligible to host UEFA Champions League Finals,[247] which Atatürk Olympic Stadium did in 2005, and UEFA Europa League (formerly UEFA Cup) Finals,[248] which Şükrü Saracoğlu Stadium did in 2009. Türk Telekom Arena is noted as an elite UEFA stadium by its architects.[249]

出典

- ^ “The Results of Address Based Population Registration System, 2021”. Turkish Statistical Institute (2021年2月4日). 2022年4月25日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Province by Province / Town Center and Town / Village Population – 2011”. Address Population-Based Registration System (ABPRS) Database. The Turkish Statistical Institute (2011年). 2012年5月9日閲覧。

- ^ a b Mossberger, Clarke & John 2012, p. 145

- ^ Demographia: World Urban Areas & Population Projections

- ^ Statistical Institute page

- ^ a b 日高ら(1990)、p.10-11、1.イスタンブールへようこそ、- 歴史を辿る<神話の中で生まれた町>

- ^ 日高ら(1990)、p.6-7、1.イスタンブールへようこそ、- イスタンブールに魅せられて

- ^ a b c WCTR Society; Unʼyu Seisaku Kenkyū Kikō 2004, p. 281

- ^ a b c 井上(1990)、p.56-58、2-「新しいローマ」の登場、憧れの都コンスタンティノープル

- ^ Çelik 1993, p. xv

- ^ a b Masters & Ágoston 2009, pp. 114–5

- ^ Dumper & Stanley 2007, p. 320

- ^ a b Turan 2010, p. 224

- ^ a b c “Population and Demographic Structure”. Istanbul 2010: European Capital of Culture. Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (2008年). 2012年3月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b Weiner, Miriam B. “World's Most Visited Cities”. U.S. News & World Report. 2012年5月21日閲覧。

- ^ “The World According to GaWC 2010”. Globalization and World Cities (GaWC) Study Group and Network. Loughborough University. 2012年5月8日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e “OECD Territorial Reviews: Istanbul, Turkey”. Policy Briefs. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2008年3月). 2012年8月20日閲覧。

- ^ Global Cities 2017 AT Kearney 2017年公表 2017年8月4日閲覧。

- ^ a b “IOC selects three cities as Candidates for the 2020 Olympic Games”. The International Olympic Committee (2012年5月24日). 2012年6月18日閲覧。

- ^ 日高ら(1990)、p.7-9、1.イスタンブールへようこそ、- 雑踏の中で

- ^ Herodotus Histories 4.144, translated in De Sélincourt 2003, p. 288

- ^ a b Isaac 1986, p. 199

- ^ Roebuck 1959, p. 119, also as mentioned in Isaac 1986, p. 199

- ^ Lister 1979, p. 35

- ^ a b Freely 1996, p. 10

- ^ a b c Room 2006, pp. 177

- ^ Gregory 2010, pp. 62–3

- ^ a b Masters & Ágoston 2009, p. 286

- ^ Masters & Ágoston 2009, pp. 226–7

- ^ Finkel 2005, pp. 57, 383

- ^ Göksel & Kerslake 2005, p. 27

- ^ Room 2006, pp. 177–8

- ^ Göktürk, Soysal & Türeli 2010, p. 7

- ^ Keyder 1999, p. 95

- ^ Pliny the Elder, book IV, chapter XI:

"On leaving the Dardanelles we come to the Bay of Casthenes, ... and the promontory of the Golden Horn, on which is the town of Byzantium,a a free state, formerly called Lygos; it is 711 miles from Durazzo, ..." ) - ^ a b Janin, Raymond (1964). Constantinople byzantine. Paris: Institut Français d'Études Byzantines. p. 10f.

- ^ a b Georgacas, Demetrius John (1947). “The Names of Constantinople”. Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 78: 347–67. doi:10.2307/283503. JSTOR 283503.

- ^ a b c d Necdet Sakaoğlu (1993/94a): "İstanbul'un adları" ["The names of Istanbul"]. In: 'Dünden bugüne İstanbul ansiklopedisi', ed. Türkiye Kültür Bakanlığı, Istanbul.

- ^ According to the Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum, vol. 164 (Stuttgart 2005), column 442, there is no evidence for the tradition that Constantine officially dubbed the city "New Rome" (Nova Roma or Nea Rhome). Commemorative coins that were issued during the 330s already refer to the city as Constantinopolis (see e.g. Michael Grant, The climax of Rome (London 1968), p. 133). It is possible that the Emperor called the city "Second Rome" (Deutera Rhome) by official decree, as reported by the 5th-century church historian Socrates of Constantinople.

- ^ Bartholomew, Archbishop of Constantinople, New Rome and Ecumenical Patriarch

- ^ Finkel, Caroline, Osman's Dream, (Basic Books, 2005), 57; "Istanbul was only adopted as the city's official name in 1930..".

- ^ An alternative derivation, directly from Constantinople, was entertained as an hypothesis by some researchers in the 19th century but is today regarded as obsolete; see Sakaoğlu (1993/94a: 254) for references.

- ^ Detailed history at Pylos#The Name of Navarino

- ^ Bourne, Edward G. (1887). “The Derivation of Stamboul”. American Journal of Philology (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 8 (1): 78–82. doi:10.2307/287478. JSTOR 287478.

- ^ G. Necipoĝlu "From Byzantine Constantinople to Ottoman Kostantiniyye: Creation of a Cosmopolitan Capital and Visual Culture under Sultan Mehmed II" Ex. cat. "From Byzantion to Istanbul: 8000 Years of a Capital", June 5 - September 4, 2010, Sabanci University Sakip Sabanci Museum, Istanbul. Istanbul: Sakip Sabanci Museum, 2010 p. 262

- ^ Necdet Sakaoğlu (1993/94b): "Kostantiniyye". In: 'Dünden bugüne İstanbul ansiklopedisi', ed. Türkiye Kültür Bakanlığı, Istanbul.

- ^ A.C. Barbier de Meynard (1881): Dictionnaire Turc-Français. Paris: Ernest Leroux.

- ^ Stanford and Ezel Shaw (1977): History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Vol II, p. 386; Robinson (1965), The First Turkish Republic, p. 298

- ^ Arab historian Al Masudi writes that the Greek calls the city Stanbulin. Necipoĝlu (2010) p. 262

- ^ a b "Istanbul", in Encyclopedia of Islam.

- ^ H. G. Dwight (1915): Constantinople Old and New. New York: Scribner's. [要ページ番号]

- ^ Edmondo De Amicis (1878) Costantinopoli Milano, Treves, passim

- ^ http://www.aii-t.org/j/maqha/magazine/osman/20080219.htm

- ^ Rainsford, Sarah (2009年1月10日). “Istanbul's ancient past unearthed”. BBC 2010年4月21日閲覧。

- ^ Düring 2010, pp. 181–2

- ^ Çelik 1993, p. 11

- ^ De Souza 2003, p. 88

- ^ Freely 1996, p. 20

- ^ Freely 1996, p. 22

- ^ Grant 1996, pp. 8–10

- ^ Limberis 1994, pp. 11–2

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 77

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 212

- ^ a b Barnes 1981, p. 222

- ^ a b 井上(1990)、p.58-60、2-「新しいローマ」の登場、私の前を歩いている御方が

- ^ a b c Gregory 2010, p. 63

- ^ a b Klimczuk & Warner 2009, p. 171

- ^ Dash, Mike (2012年3月2日). “Blue Versus Green: Rocking the Byzantine Empire”. Smithsonian Magazine. The Smithsonian Institution. 2012年7月30日閲覧。

- ^ Dahmus 1995, p. 117

- ^ Cantor 1994, p. 226

- ^ Morris 2010, pp. 109–18

- ^ Gregory 2010, pp. 324–9

- ^ Gregory 2010, pp. 330–3

- ^ Gregory 2010, p. 340

- ^ Gregory 2010, pp. 341–2

- ^ Reinert 2002, pp. 258–60

- ^ Baynes 1949, p. 47

- ^ 井上(1990)、p.238-240、6-ビサンティン帝国の落日、ビサンティン帝国の滅亡

- ^ Gregory 2010, pp. 394–9

- ^ 井上(1990)、p.114-116、3-「パンとサーカス」の終焉、「髭の皇帝」は誰か

- ^ a b Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, pp. 307

- ^ Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, pp. 306–7

- ^ Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, pp. 735–6

- ^ a b Chandler, Tertius; Fox, Gerald (1974). 3000 Years of Urban Growth. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-785109-9.

- ^ Shaw & Shaw 1977, pp. 4–6, 55

- ^ Çelik 1993, pp. 87–9

- ^ a b Harter 2005, p. 251

- ^ 「オリエント急行の時代 ヨーロッパの夢の軌跡」p183 平井正 2007年1月25日発行 中央公論新社

- ^ Shaw & Shaw 1977, pp. 230, 287, 306およびオスマン債務管理局の項目に付した出典

- ^ Çelik 1993, p. 31

- ^ 「バルカン 歴史と現在」p308-309 ジョルジュ・カステラン著 山口俊章訳 1994年7月発行 サイマル出版会

- ^ Landau 1984, p. 50

- ^ Dumper & Stanley 2007, p. 39

- ^ Keyder 1999, pp. 11–2, 34–6

- ^ Efe & Cürebal 2011, pp. 718–9

- ^ “TÜRK BELEDİYECİLİĞİNİN GELİŞİM SÜRECİ”. www.mevzuatdergisi.com. 2022年2月6日閲覧。

- ^ “BÜYÜKŞEHİR BELEDİYESİ KANUNU” (10/7/2004). 2022年2月6日閲覧。

- ^ “トルコ爆発関与か、5人拘束 クルド人やガガウス人―ブルガリア:時事ドットコム”. 時事ドットコム. 2022年12月10日閲覧。

- ^ “Districts”. Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality. 2011年12月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “History of Local Governance in Istanbul”. Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality. 2011年12月21日閲覧。

- ^ “İstanbul İl ve İlçe Alan Bilgileri” [Istanbul Province and District Area Information] (Turkish). Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality. 2010年6月20日閲覧。

- ^ “Jurisdiction”. Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality. 2011年12月21日閲覧。

- ^ “Istanbul from a Bird's Eye View”. Governorship of Istanbul. 2010年6月13日閲覧。

- ^ a b “The Topography of İstanbul”. Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. 2012年6月19日閲覧。

- ^ Revkin, Andrew C. (2010年2月24日). “Disaster Awaits Cities in Earthquake Zones”. The New York Times 2010年6月13日閲覧。

- ^ Parsons, Tom; Toda, Shinji; Stein, Ross S.; Barka, Aykut; Dieterich, James H. (2000). “Heightened Odds of Large Earthquakes Near Istanbul: An Interaction-Based Probability Calculation”. Science (Washington, D.C.: The American Association for the Advancement of Science) 288 (5466): 661–5. doi:10.1126/science.288.5466.661. PMID 10784447.

- ^ Traynor, Ian (2006年12月9日). “A Disaster Waiting to Happen – Why a Huge Earthquake Near Istanbul Seems Inevitable”. The Guardian (UK) 2010年6月13日閲覧。

- ^ Kottek, Markus; Grieser, Jürgen; Beck, Christoph; Rudolf, Bruno; Rube, Franz (June 2006). “World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated”. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 15 (3): 259–263. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130 2011年2月27日閲覧。.

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). “Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification”. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 4 (2): 439–473. doi:10.5194/hessd-4-439-2007 2011年2月27日閲覧。.

- ^ a b Efe & Cürebal 2011, pp. 716–7

- ^ a b “Weather – Istanbul”. World Weather. BBC Weather Centre. 2012年10月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Istanbul Enshrouded in Dense Fog”. Turkish Daily News (2005年1月14日). 2012年10月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Thick Fog Causes Disruption, Flight Delays in İstanbul”. Today's Zaman (2009年11月23日). 2012年10月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Dense Fog Disrupts Life in Istanbul”. Today's Zaman (2010年11月6日). 2012年10月15日閲覧。

- ^ a b Pelit, Attila. “When to Go to Istanbul”. TimeOut Istanbul. 2011年12月19日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Resmi İstatistikler (İl ve İlçelerimize Ait İstatistiki Veriler)” [Official Statistics (Statistical Data of Provinces and Districts) - Istanbul] (Turkish). Turkish State Meteorological Service. 2012年9月22日閲覧。

- ^ Quantic 2008, p. 155

- ^ Kindap, Tayfin (2010-01-19). “A Severe Sea-Effect Snow Episode Over the City of Istanbul”. Natural Hazards 54 (3): 703–23. ISSN 1573-0840 2012年10月15日閲覧。.

- ^ “Istanbul Winds Battle Over the City”. Turkish Daily News (2009年10月17日). 2012年10月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Yıllık Toplam Yağış Verileri” [Annual Total Participation Data: Istanbul, Turkey] (Turkish). Turkish State Meteorological Service. 2012年7月6日閲覧。

- ^ “İstanbul Bölge Müdürlüğü'ne Bağlı İstasyonlarda Ölçülen Ekstrem Değerler” [Extreme Values Measured in Istanbul Regional Directorate] (Turkish). Turkish State Meteorological Service. 2010年7月27日閲覧。

- ^ “March 1987 Cyclone (Blizzard) over the Eastern Mediterranean and Balkan Region Associated with Blocking”. American Meteorological Society. 2010年7月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Weather Information for Istanbul”. 2010年3月6日閲覧。

- ^ [1]

- ^ “BBC - Weather Centre - World Weather - Average Conditions - Istanbul”. 2010年3月6日閲覧。

- ^ Çelik 1993, pp. 70, 169

- ^ Çelik 1993, p. 127

- ^ a b c “Besiktas: The Black Eagles of the Bosporus”. FIFA. 2012年4月8日閲覧。

- ^ Moonan, Wendy (1999年10月29日). “For Turks, Art to Mark 700th Year”. The New York Times. 2012年7月4日閲覧。

- ^ Oxford Business Group 2009, p. 105

- ^ Karpat 1976, pp. 78–96

- ^ Yavuz, Ercan (2009年6月8日). “Gov't launches plan to fight illegal construction”. Today's Zaman 2011年12月20日閲覧。

- ^ Boyar & Fleet 2010, p. 247

- ^ Taylor 2007, p. 241

- ^ “Water Supply Systems, Reservoirs, Charity and Free Fountains, Turkish Baths”. Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. 2012年4月29日閲覧。

- ^ Time Out Guides 2010, p. 212

- ^ a b Chamber of Architects of Turkey 2006, pp. 80, 118

- ^ Chamber of Architects of Turkey 2006, p. 176

- ^ Gregory 2010, p. 138

- ^ Freely 2000, p. 283

- ^ Necipoğlu 1991, pp. 180, 136–137

- ^ Çelik 1993, p. 159

- ^ Çelik 1993, pp. 133–34, 141

- ^ もう1都市は同じ大都市自治体のイズミットでこちらはコジャエリ県とほぼ同一の範囲

- ^ “Büyükşehir Belediyesi Kanunu” [Metropolitan Municipal Law] (Turkish). Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi (2004年7月10日). 2010年11月30日閲覧。 “Bu Kanunun yürürlüğe girdiği tarihte; büyükşehir belediye sınırları, İstanbul ve Kocaeli ilinde, il mülkî sınırıdır. (On the date this law goes in effect, the metropolitan city boundaries, in the provinces of İstanbul and Kocaeli, are those of the province.)”

- ^ Çelik 1993, pp. 42–8

- ^ Kapucu & Palabiyik 2008, p. 145

- ^ Taşan-Kok 2004, p. 87

- ^ Wynn 1984, p. 188

- ^ Taşan-Kok 2004, pp. 87–8

- ^ a b Kapucu & Palabiyik 2008, pp. 153–5

- ^ Erder, Sema (November 2009). “Local Governance in Istanbul” (pdf). Istanbul: City of Intersections. Urban Age (London: London School of Economics): 46 2012年7月16日閲覧。.

- ^ a b Kapucu & Palabiyik 2008, p. 156

- ^ a b “Metropolitan Executive Committee”. Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality. 2011年12月21日閲覧。

- ^ Kapucu & Palabiyik 2008, pp. 155–6

- ^ “The Mayor's Biography”. Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality. 2011年12月21日閲覧。

- ^ 在イスタンブール日本国総領事館 イスタンブールについて

- ^ “Organizasyon” [Organization] (Turkish). Istanbul Special Provincial Administration. 2011年12月21日閲覧。

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2008, p. 206

- ^ “Encümen Başkanı” [Head of the Council] (Turkish). Istanbul Special Provincial Administration. 2011年12月21日閲覧。

- ^ “Address Based Population Registration System Results of 2010” (doc). Turkish Statistical Institute (2011年1月28日). 2011年12月24日閲覧。

- ^ Morris 2010, p. 113

- ^ Chandler 1987, pp. 463–505

- ^ a b “Frequently Asked Questions”. World Urbanization Prospects, the 2011 Revision. The United Nations (2012年4月5日). 2012年9月20日閲覧。

- ^ a b “File 11a: The 30 Largest Urban Agglomerations Ranked by Population Size at Each Point in Time, 1950–2025” (xls). World Urbanization Prospects, the 2011 Revision. The United Nations (2012年4月5日). 2012年9月20日閲覧。

- ^ Kamp, Kristina (2010年2月17日). “Starting Up in Turkey: Expats Getting Organized”. Today's Zaman. 2012年3月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Social Structure Survey 2006”. KONDA Research (2006年). 2012年3月27日閲覧。 (Note: Accessing KONDA reports directly from KONDA's own website requires registration.)

- ^ “Turkey”. The World Factbook. The Central Intelligence Agency (2012年6月28日). 2012年7月6日閲覧。

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. “Turkey: International Religious Freedom Report 2007”. U.S. Department of State. 2012年3月27日閲覧。

- ^ Davidson & Gitlitz 2002, p. 180

- ^ “History of the Ecumenical Patriarch”. The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. 2012年6月20日閲覧。

- ^ Çelik 1993, p. 38

- ^ Athanasopulos 2001, p. 82

- ^ “The Greek Minority and its foundations in Istanbul, Gokceada (Imvros) and Bozcaada (Tenedos)”. Hellenic Republic Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2011年3月21日). 2012年6月21日閲覧。

- ^ Khojoyan, Sara (2009年10月16日). “Armenian in Istanbul: Diaspora in Turkey welcomes the setting of relations and waits more steps from both countries”. Armenia Now. 2012年6月21日閲覧。

- ^ Masters & Ágoston 2009, pp. 520–1

- ^ Wedel 2000, p. 182

- ^ Zalewski, Piotr (2012年1月9日). “Istanbul: Big Trouble in Little Kurdistan”. TIME. 2012年6月23日閲覧。

- ^ “Can't They Get Along Anymore?”. The Economist (2005年9月8日). 2012年6月23日閲覧。

- ^ Rôzen 2002, pp. 55–8, 49

- ^ Rôzen 2002, pp. 49–50

- ^ Brink-Danan 2011, p. 176

- ^ ʻAner 2005, p. 367

- ^ Schmitt 2005, passim

- ^ “III – Which are the largest city economies in the world and how might this change by 2025?”. PricewaterhouseCoopers (2009年11月). 2012年3月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Presentation of Reference City: Istanbul”. Urban Green Environment (2001年). 2011年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ Melby, Caleb (2012年3月16日). “Moscow Beats New York, London In List Of Billionaire Cities”. Forbes. 2012年3月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Dış Ticaretin Lokomotifi İstanbul” [Istanbul is the Locomotive of Foreign Trade] (Turkish). NTV-MSNBC (2006年2月13日). 2012年3月28日閲覧。

- ^ CNN Türk: Dış ticaretin lokomotifi İstanbul (Istanbul is the locomotive of foreign trade)

- ^ Odabaşı, Attila; Aksu, Celal; Akgiray, Vedat (December 2004). “The Statistical Evolution of Prices on the Istanbul Stock Exchange”. The European Journal of Finance (London: Routledge) 10 (6): 510–25. doi:10.1080/1351847032000166931.

- ^ “History of the Bank”. The Ottoman Bank Archives and Research Centre. 2012年3月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Milestones in ISE History”. Istanbul Stock Exchange (2012年). 2012年3月28日閲覧。

- ^ Oxford Business Group 2009, p. 112

- ^ Jones, Sam, and agencies (2011年4月27日). “Istanbul's new Bosphorus canal 'to surpass Suez or Panama'”. The Guardian. 2012年4月29日閲覧。

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2008, p. 80

- ^ “Ports of Turkey”. Cerrahogullari T.A.S.. 2012年8月28日閲覧。

- ^ Cavusoglu, Omer (2010年3月). “Summary on the Haydarpasa Case Study Site”. Cities Programme. London School of Economics. 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ “What Role for Turkish Ports in the Regional Logistics Supply Chains?”. International Conference on Information Systems and Supply Chain (–2008-05-30). 2012年8月28日閲覧。

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2008 p82

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2008, p. 143

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2008 p81

- ^ “Urban Tourism: An Analysis of Visitors to Istanbul” (英語). Vienna University of Economics and Business. 2019年1月3日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Istanbul '10”. Turkey Tourism Market Research Reports. Istanbul Valuation and Consulting (2010年). 2012年3月29日閲覧。 (n.b. Source indicates that the Topkapı Palace Museum and the Hagia Sophia together bring in 55 million TL, approximately $30 million in 2010, on an annual basis.)

- ^ “İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Resmi Web Sitesi”. Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (IMMWEBl). 2006年11月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2007年1月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Financial sector” (PDF). Foreign Economic Relations Board Turkey DEIK. 2006年12月18日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2007年1月1日閲覧。

- ^ “World Gold Council > jewellery:Turkey”. World Gold Council. 2007年1月1日閲覧。

- ^ [2] 無許可の花火工房爆発、20人死亡、トルコ 2008年02月01日 01:31 AFP

- ^ Baytop T. Türk Eczacılık Tarihi Araştırmaları (History of Turkish Pharmacy Researches) Istanbul. 2000:12-75.

- ^ Dogan UVEY*, Ayse Nur GOKCE*, Ibrahim BASAGAOGLU (2004) "Pharmaceutical Industry in Turkey" in 38th International Medical History Congress in Istanbul

- ^ Hürriyet: 2006’da Türkiye’ye gelen turist başına harcama 728 dolara indi

- ^ Sabah: Turist sayısı genelde düştü İstanbul'da arttı

- ^ [3]

- ^ “EIBTM 2007 - The Global Meetings & Incentive Exhibition for the MICE Industry”. Reed Exhibitions Limited (member of the Association of Event Organisers (AEO)). 2006年3月11日閲覧。 [リンク切れ]

- ^ Göktürk, Soysal & Türeli 2010, p. 8

- ^ Reisman 2006, p. 88

- ^ Göktürk, Soysal & Türeli 2010, pp. 2–4

- ^ a b “İstanbul – Archaeology Museum”. Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism. 2012年4月19日閲覧。

- ^ a b Göktürk, Soysal & Türeli 2010, pp. 221–3

- ^ Göktürk, Soysal & Türeli 2010, pp. 223–4

- ^ 『世界の美しい階段』エクスナレッジ、2015年、173頁。ISBN 978-4-7678-2042-2。

- ^ Hansen, Suzy (2012年2月10日). “The Istanbul Art-Boom Bubble”. The New York Times. 2012年4月19日閲覧。

- ^ Göktürk, Soysal & Türeli 2010, pp. 130–1

- ^ Göktürk, Soysal & Türeli 2010, pp. 133–4

- ^ Göktürk, Soysal & Türeli 2010, p. 146

- ^ Göktürk, Soysal & Türeli 2010, p. 165

- ^ Nikitin, Nikolaj (2012年3月6日). “Golden Age for Turkish Cinema”. Credit-Suisse. 2012年7月6日閲覧。

- ^ Köksal 2012, pp. 24–5

- ^ “History”. The Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts. 2012年4月13日閲覧。

- ^ Gibbons, Fiachra (2011年9月21日). “10 of the Best Exhibitions at the Istanbul Biennial”. The Guardian. 2012年4月13日閲覧。

- ^ Hensel, Michael; Sungurogl, Defne; Ertaş, Hülya, eds (2010-01-22). “Turkey at the Threshold”. Architectural Design (London: John Wiley & Sons) 80 (1). ISBN 978-0-470-74319-5.

- ^ a b Köse 2009, pp. 91–2

- ^ Taşan-Kok 2004, p. 166

- ^ Emeksiz, İpek (2010年9月3日). “Abdi İpekçi Avenue to be new Champs Elysee”. Hürriyet Daily News. 2012年4月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Shopping in Singapore is Better than Paris”. CNN (2012年1月6日). 2012年4月28日閲覧。

- ^ Schäfers, Marlene (2008年7月26日). “Managing the Difficult Balance Between Tourism and Authenticity”. Hürriyet Daily News. 2012年4月29日閲覧。

- ^ Schillinger, Liesl (2011年7月8日). “A Turkish Idyll Lost in Time”. The New York Times. 2012年4月29日閲覧。

- ^ Keyder 1999, p. 34

- ^ Kugel, Seth (2011年7月17日). “The $100 Istanbul Weekend”. The New York Times. 2012年4月29日閲覧。

- ^ Knieling & Othengrafen 2009, pp. 228–34

- ^ “A Big Night Out in Istanbul – And a Big Breakfast the Morning After”. The Guardian (2012年3月23日). 2012年4月29日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Galatasaray: The Lions of the Bosporus”. FIFA. 2012年4月10日閲覧。

- ^ “UEFA Champions League 2007/08 – History – Fenerbahçe”. The Union of European Football Associations (2011年10月8日). 2012年4月10日閲覧。

- ^ “Takımlar” (トルコ語). Türkiye Basketbol Ligi. 2019年1月3日閲覧。

- ^ “List of Certified Athletics Facilities”. The International Association of Athletics Federations (2013年1月1日). 2013年1月2日閲覧。

- ^ “2008/09: Pitmen strike gold in Istanbul”. The Union of European Football Associations (2009年5月20日). 2012年4月10日閲覧。

- ^ Aktaş, İsmail (2012年3月14日). “Aşçıoğlu Sues Partners in Joint Project Over Ali Sami Yen Land”. Hürriyet Daily News. 2012年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Regulations of the UEFA European Football Championship 2010–12” (pdf). The Union of European Football Associations. p. 14. 2012年4月10日閲覧。

- ^ “Regulations of the UEFA Europa League 2010/11” (pdf). The Union of European Football Associations. p. 17. 2012年4月10日閲覧。

- ^ “Türk Telekom Arena Istanbul”. 'asp' Architekten. 2012年7月5日閲覧。

- ^ “2010 FIBA World Championship Istanbul: Arenas”. FIBA. 2012年4月10日閲覧。

- ^ “Istanbul – Arenas”. FIBA (2010年). 2012年6月29日閲覧。

- ^ “Fenerbahce Ulker's new home, Ulker Sports Arena, opens”. Euroleague Basketball (2012年1月24日). 2012年6月29日閲覧。

- ^ Wilson, Stephen (2011年9月2日). “2020 Olympics: Six cities lodge bids for the games”. The Christian Science Monitor. 2012年6月29日閲覧。

- ^ “UEFA Announce New Euro 2020 Bid Process”. The Independent (2012年5月16日). 2012年6月29日閲覧。

- ^ 安倍首相「本当にうれしい 」東京五輪決定 cnn.co.jp 2013.09.07

- ^ “Events”. FIA World Touring Car Championship (2012年). 2012年6月29日閲覧。

- ^ “The Circuits”. European Le Mans Series (2012年). 2012年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ Richards, Giles (2011年4月22日). “Turkey Grand Prix Heads for the Scrapyard Over $26m Price Tag”. The Guardian. 2012年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ “2012 Yarış Programı ve Genel Yarış Talimatı” [2012 Race Schedule and General Sailing Instructions] (Turkish). The Istanbul Sailing Club (2012年). 2012年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ Turkish Daily News (2008年8月23日). “Sailing Week Starts in Istanbul”. Hürriyet Daily News. 2012年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ “About Us”. The Turkish Offshore Racing Club (2012年3月31日). 2012年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Races”. F1 Powerboat World Championship (2012年). 2012年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ Brummett 2000, pp. 11, 35, 385–6

- ^ a b c d “Country Profile: Turkey”. The Library of Congress Federal Research Division (2008年8月). 2012年5月8日閲覧。

- ^ “Gazete Net Satışları” [Net Sales of Newspapers] (Turkish). Medyatava (2012年4月30日). 2012年5月8日閲覧。

- ^ a b “TRT – Radio”. The Turkish Radio and Television Corporation. 2012年5月8日閲覧。

- ^ Time Out Guides 2010, p. 224

- ^ “TRT – Television”. The Turkish Radio and Television Corporation. 2012年5月8日閲覧。

- ^ Norris 2010, p. 184

- ^ “Chris Morris”. BBC. 2012年5月8日閲覧。

- ^ “History”. Istanbul University (2011年8月11日). 2012年8月20日閲覧。

- ^ “History”. Istanbul Technical University. 2012年7月4日閲覧。

- ^ “University Profile: Istanbul Technical University, Turkey”. Board of European Students of Technology. 2012年3月30日閲覧。

- ^ “State Universities”. The Turkish Council of Higher Education. 2012年3月30日閲覧。

- ^ “About Marmara”. Marmara University. 2012年7月4日閲覧。

- ^ “General Information”. Ankara: Istanbul Medeniyet University. 2012年3月30日閲覧。

- ^ a b Doğramacı, İhsan (2005年8月). “Private Versus Public Universities: The Turkish Experience” (DOC). 18th International Conference on Higher Education. 2012年3月30日閲覧。

- ^ “History of RC”. Robert College (2012年). 2012年10月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Private Universities”. The Turkish Council of Higher Education. 2012年3月30日閲覧。

- ^ “2007 Yılına Ait Veriler” [Data for 2007] (Turkish). Governorship of Istanbul. 2011年8月2日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2012年3月30日閲覧。

- ^ “Historique” [History] (French). Galatasaray University. 2012年3月30日閲覧。

- ^ “Millî Eğitim Bakanlığı Anadolu Liseleri Yönetmeliği” [Ministry of Education Regulation on Anatolian High Schools] (Turkish). Ministry of Education (1999年11月5日). 2012年3月30日閲覧。

- ^ “Galatasaray Lisesi”. Galatasaray High School. 2012年7月4日閲覧。

- ^ “The History of the Italian School”. Liceo Italiano. 2012年7月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Principles of Education”. Darüşşafaka High School. 2012年7月6日閲覧。

- ^ “Kabataş Erkek Lisesi” (Turkey). Kabataş Erkek Lisesi. 2012年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ “KAL Uygulamalı Yabancı Dil Laboratuvarı” [KAL Applied Foreign Language Lab] (Turkish). Kadıköy Anadolu Lisesi. 2012年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Istanbul and the History of Water in Istanbul”. Istanbul Water and Sewerage Administration. 2007年9月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2006年3月11日閲覧。

- ^ Tigrek & Kibaroğlu 2011, pp. 33–4

- ^ “İSKİ Administration”. Istanbul Water and Sewerage Administration. 2007年9月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2012年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Silahtarağa Power Plant”. SantralIstanbul. 2012年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Short History of Electrical Energy in Turkey”. Turkish Electricity Transmission Company (2001年). 2009年11月28日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2012年7月5日閲覧。

- ^ “Central Post Office”. Emporis. 2012年4月4日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d “About Us | Brief History”. The Post and Telegraph Organization. 2012年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Masters & Ágoston 2009, p. 557

- ^ Shaw & Shaw 1977, p. 230

- ^ a b “About Türk Telekom: History”. Türk Telekom. 2012年3月31日閲覧。

- ^ Sanal 2011, p. 85

- ^ Oxford Business Group 2009, p. 197

- ^ Oxford Business Group 2009, p. 198

- ^ Connell 2010, pp. 52–3

- ^ Papathanassis 2011, p. 63

- ^ Google Maps – Istanbul Overview (Map). Cartography by Google, Inc. Google, Inc. 2012年4月1日閲覧。

- ^ Efe & Cürebal 2011, p. 720

- ^ a b ERM Group (Germany and UK) and ELC-Group (Istanbul) (January 2011 2011). “Volume I: Non Technical Summary (NTS)”. Eurasia Tunnel Environmental and Social Impact Assessment. The European Investment Bank. 2012年7月4日閲覧。

- ^ a b Letsch, Constanze (2012年6月8日). “Plan for New Bosphorus Bridge Sparks Row Over Future of Istanbul”. The Guardian. 2012年7月4日閲覧。

- ^ Songün, Sevim (2010年7月16日). “Istanbul Commuters Skeptical of Transit Change”. Hürriyet Daily News. 2012年7月5日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Chronological History of IETT”. Istanbul Electricity, Tramway and Tunnel General Management. 2012年4月1日閲覧。

- ^ “T1 Bağcılar–Kabataş Tramvay Hattı” [T1 Bağcılar–Kabataş Tram Line] (Turkish). İstanbul Ulaşım A.Ş. (Istanbul Transport Corporation). 2012年8月20日閲覧。

- ^ “Tunnel”. Istanbul Electricity, Tramway and Tunnel. 2012年4月3日閲覧。 (Note: It is apparent this is merely a machine translation of the original Turkish page.)

- ^ “F1 Taksim–Kabataş Füniküler Hattı” [F1 Bağcılar–Kabataş Funicular Line] (Turkish). İstanbul Ulaşım A.Ş. (Istanbul Transport Corporation). 2012年8月20日閲覧。

- ^ “Raylı Sistemler” [Rail Systems] (Turkish). İstanbul Ulaşım A.Ş. (Istanbul Transport Corporation). 2012年8月20日閲覧。

- ^ “Ağ Haritaları” [Network Maps] (Turkish). İstanbul Ulaşım A.Ş. (Istanbul Transport Corporation). 2012年8月20日閲覧。

- ^ “Turkey: Connecting Continents”. Economic Updates. Oxford Business Group (2012年3月7日). 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ Efe & Cürebal 2011, p. 723

- ^ “Public Transportation in Istanbul”. Istanbul Electricity, Tramway and Tunnel General Management. 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Metrobus”. Istanbul Electricity, Tramway and Tunnel General Management. 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Interaktif Haritalar | İç Hatlar” [Interactive Map of Timetables | Inner-City Lines] (Turkish). İDO. 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Dış Hatlar” [Interactive Map of Timetables | Inter-City Lines] (Turkish). İDO. 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ Grytsenko, Sergiy (2011年9月26日). “EBRD Supports Privatisation of Ferry Operations in Istanbul”. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. 2012年4月4日閲覧。

- ^ “Liman Hizmetleri” [Port Services] (Turkish). Turkey Maritime Organization (2011年2月10日). 2012年8月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Bölgesel Yolcu Trenleri” [Regional Passenger Trains] (Turkish). Turkish State Railways. 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ Keenan, Steve (2012年6月22日). “How Your Greek Summer Holiday Can Help Save Greece”. The Guardian. 2012年9月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Haydarpasa Train Station”. Emporis. 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ Head, Jonathan (2010年2月16日). “Iraq – Turkey railway link re-opens”. BBC. 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Transports to Middle-Eastern Countries”. Turkish National Railways. 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ Akay, Latifa (2012年2月5日). “2012 Sees End of Line for Haydarpaşa Station”. Today's Zaman. 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ 世界初の大陸間海底トンネル、トルコで開通 2013年10月30日 08:33 AFP

- ^ “İstanbul Otogarı” [Istanbul Bus Station] (Turkish). Avrasya Terminal İşletmeleri A.Ş. (Eurasian Terminal Management, Inc.). 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Eurolines Germany–Deutsche Touring GmbH–Europabus”. Touring. 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ Strauss, Delphine (2009年11月25日). “Sabiha Gökçen: New Terminal Lands On Time and Budget”. The Financial Times. 2012年7月4日閲覧。

- ^ “Yolcu Trafiği (Gelen-Giden)” (pdf) [Passenger Traffic (Incoming-Outgoing)] (Turkish). General Directorate of State Airports Authority. 2012年4月3日閲覧。

- ^ “Sabiha Gökçen Named World's Fastest Growing Airport”. Today's Zaman (2011年8月18日). 2012年4月4日閲覧。

- ^ Rogers, Simon (2012年5月4日). “The World's Top 100 Airports: Listed, Ranked, and Mapped”. The Guardian. 2012年7月6日閲覧。

- ^ “Sister Cities of Istanbul”. 2009年7月1日閲覧。

- ^ Erdem, Selim Efe (2009年7月1日). “İstanbul'a 49 kardeş” (Turkish). Radikal 2009年7月22日閲覧. "49 sister cities in 2003"

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p IBB (2010 [last update]). “kardes_sehir_isbirligi_ve_iyi_niyet_anlasmasi_imzalanan_seh.pdf (application/pdf Object)”. ibb.gov.tr. 2011年5月30日閲覧。

- ^ “Berlin's international city relations”. Berlin Mayor's Office. 2009年7月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Barcelona internacional - Ciutats agermanades” (Spanish). © 2006-2009 Ajuntament de Barcelona. 2009年7月13日閲覧。

- ^ “Sister cities of Budapest” (Hungarian). Official Website of Budapest. 2009年7月1日閲覧。

- ^ www.praha-mesto.cz. “Partner cities”. 2008年10月9日閲覧。

- ^ “Saint Petersburg in figures - International and Interregional Ties”. Saint Petersburg City Government. 2008年11月23日閲覧。

- ^ http://www.ibb.gov.tr/tr-TR/Pages/Haber.aspx?NewsID=20463

イスタンブールと同じ種類の言葉

| 港湾都市に関連する言葉 | アレクサンドリア アンカレジ イスタンブール イズミル エーラト |

「イスタンブール」に関係したコラム

-

2012年6月現在の日本の証券取引所、および、世界各国の証券取引所の一覧です。▼日本東京証券取引所(東証)大阪証券取引所(大証)名古屋証券取引所(名証)福岡証券取引所(福証)札幌証券取引所(札証)TO...

-

株価指数は、証券取引所に上場している銘柄を一定の基準で選出し、それらの銘柄の株価を一定の計算方法で算出したものです。例えば、日本の株価指数の日経平均株価(日経平均、日経225)は、東京証券取引所(東証...

- イスタンブールのページへのリンク