アスパルテーム

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2024/01/01 06:06 UTC 版)

| アスパルテーム[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

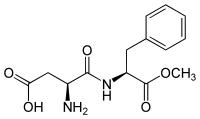

N-(L-α-アスパルチル)-L-フェニルアラニン 1-メチルエステル | |

| 識別情報 | |

| CAS登録番号 | 22839-47-0 |

| ChemSpider | 118630 |

| E番号 | E951 (その他) |

| KEGG | C11045 |

| |

| 特性 | |

| 化学式 | C14H18N2O5 |

| 融点 |

246–247 ℃ |

| 沸点 |

分解 |

| 水への溶解度 | 10 (g/L) (20 ℃の場合) |

| 危険性 | |

| NFPA 704 | |

| 特記なき場合、データは常温 (25 °C)・常圧 (100 kPa) におけるものである。 | |

アスパルテームの安全性は、その発見以来、動物実験、臨床研究、疫学研究、市販後調査などによって、広く研究されており、最も厳密に評価された食品成分の1つである[6][7]。複数の権威あるレビュ ーによって一日摂取許容量(ADI)の上限で安全に摂取できることが確かめられている[6][8][9][10]。英国食品基準庁(FSA)[11]、欧州食品安全機関(EFSA)[12]、カナダ保健省など[13]、各国の100を超える規制機関から使用が承認されている[3][14][15]。

性質

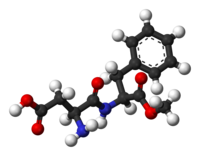

アスパルテームは、アスパラギン酸とフェニルアラニンという2つのアミノ酸を結合させたジペプチドである[5]。アスパラギン酸とフェニルアラニンが特定の方法で結合してアスパルテームを形成すると、強い甘味を持つ物質が生成される[16]。

| 甘味料 | 甘味度 |

|---|---|

| 砂糖 | 1 |

| アスパルテーム | 200 |

| アセスルファムカリウム | 250 |

| スクラロース | 750 |

砂糖の約180 - 200倍の甘さがあり、卓上甘味料として、または冷菓、ゼラチン、飲料、チューインガムなどに使用される[11][12][17]。砂糖と同じ1gあたり4kcalだが、同じ甘味を出すのに必要な量は1/200と非常に少なく、カロリーはごくわずかである[18][19][20]。日本では食品100gまたは飲料100ml当たり5kcal未満なら「カロリーゼロ」と表記することが可能なため、カロリーゼロではない場合もあるが、栄養学的に無視できる量である[4][21]。糖質ではないので血糖値を上げることはなく、グリセミック指数はゼロである[18][22][23]。アミノ酸を主成分とするため、ミュータンス菌の栄養源にならず、虫歯の原因にならない[5]。

他の多くのペプチドと同様に、高温または高pHに弱く、アミノ酸に加水分解(分解)することがある[24]。水に溶かしたときの安定性は、時間、温度、pHの影響を受ける[25]。弱酸性のpH2.5 - 5.5の範囲で安定であると考えられ、室温ではpH4.2で最も安定する[25]。ほとんどの清涼飲料水のpHは3 - 5で、アスパルテームは適度に安定している。

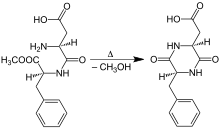

耐熱性がなく、196 °Cで分解する[24]。150 °C以上で急速に分解するが、105℃と120℃での分解は比較的遅い[25][24]。 アスパルテームは、個々の成分(L-アスパラギン酸、L-フェニルアラニン、メタノール)に分解したり、2,5-ジケトピペラジンに環化したりすることがあり、これは調理や焼成によって生成され、甘味を失う原因となる[26][27]。そのため、他の甘味料よりも製パンや焼き菓子には適していない[28][29]。

砂糖の自然な甘みに近づける、熱に強くするなどの目的で、アセスルファムカリウムなど他の非糖質系甘味料とブレンドして使用されることが多い[4][30][5]。例えば、アスパルテームとアセスルファムカリウムを1:1で併用すると甘味度が40%増強され、甘味質も砂糖に近くなる[31]。味の素の「パルスイート」カロリーゼロは、アセスルファムカリウムを配合して、熱に強くしている[31]。保存期間が長い製品では、サッカリンなどのより安定した甘味料とブレンドすることがある[32]。

許容摂取量

食品添加物の一日摂取許容量(ADI)は、「生涯にわたって毎日摂取しても健康上のリスクが認められない量を体重ベースで表したもの」と定義されている[33]。ADIは、動物実験で無毒とされた量の100分の1以下の量に設定されている[34][35]。

FAO/WHO合同食品添加物専門家会議(JECFA)や欧州食品安全機関(EFSA)、厚生労働省などは、アスパルテームについてこの値を1日あたり体重40mg/kgと設定し、アメリカ食品医薬品局(FDA)は1日あたり50mg/kgに設定している[36][37][38]。

この一日摂取許容量(ADI)40mg/kgは、「体重60kgの人は、毎日2400mgのアスパルテームを一生涯摂取し続けても、健康への悪影響は出ない」ということを示している[36][39]。たとえば、アスパルテームが使われた飲料を1日に2リットル飲んだ場合、アスパルテームの摂取量を過大に見積もっても1000mgに至らない[36]。欧州食品安全機関(EFSA)は、「体重60kgの人は、最大許容使用量を含む330mlのダイエット飲料を毎日12缶飲まないとADIに達しない」「実際の飲料はもっと低い濃度、最大許容濃度の3 - 6分の1で使用されるので、ADIに達するには36缶以上必要」と説明している[40]。

アメリカ、ヨーロッパ諸国、オーストラリアなど、世界各国におけるアスパルテームの消費量を調べた研究では、高レベルのアスパルテームの摂取でさえ、ADIをはるかに下回っていることがわかった[6][8][38]。日本での摂取量は、2022年の厚生労働省による調査では6.58mg/人/日であり、ADIの約0.3%だった[36][41]。

食品添加物のリスク評価

食品安全委員会などが行う「リスク評価(食品健康影響評価)」では、国によって食品の摂取量などの状況は異なるため、各国の現状に近い摂取量に基づきリスク評価が行われる[42]。

食品添加物については、安全性を確保するため、動物実験によって無害とされた量(無毒性量)について、その無毒性量の100分の1以上の安全係数を掛けて、人が一生涯食べ続けても健康に悪影響を与えない量、すなわち「一日摂取許容量(ADI)」が設定される[34][35][43]。摂取許容量(無毒性量の100分の1以下の量)より大幅に少ない量が法令上の基準値とされた上に、実際に使用される量は基準より更に大幅に少ない[34]。このように食品添加物は、毎日・一生食べても安全な範囲でのみ使用される[34][44]。

アスパルテームの生殖・発生毒性試験における無毒性量(NOAEL)は、ラットでは試験した最高用量の4000mg/kg体重/日、マウスでは試験した最高用量の5700mg/kg体重/日であり、生殖・発生毒性物質ではないと結論づけられている[45]。

- ^ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 861.

- ^ a b c d “Aspartame”. PubChem, National Library of Medicine, US National Institutes of Health (2023年5月27日). 2017年8月17日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2023年6月2日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g “Aspartame and Other Sweeteners in Food”. US Food and Drug Administration (2023年7月14日). 2023年7月17日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2023年7月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d “砂糖の置き換え「甘味料」はダイエットに効果なし!? WHOの勧告が波紋、砂糖と甘味料の違いと「カロリーゼロ」「ノンカロリー」食品との付き合い方”. jprime (2023年6月27日). 2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j “Perfect Guide パルスイート・カロリーゼロ 20年の歩み” (PDF). 味の素株式会社. 2023年7月17日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i EFSA National Experts (May 2010). “Report of the meetings on aspartame with national experts”. EFSA Supporting Publications 7 (5). doi:10.2903/sp.efsa.2010.ZN-002.

- ^ Sweeteners and sugar alternatives in food technology. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. (2006). p. 94. ISBN 978-1-4051-3434-7

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q “Aspartame: a safety evaluation based on current use levels, regulations, and toxicological and epidemiological studies”. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 37 (8): 629–727. (2007). doi:10.1080/10408440701516184. PMID 17828671.

- ^ “Food Standards Australia New Zealand: Aspartame – what it is and why it's used in our food”. 2008年10月14日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年12月9日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j “Aspartame: review of safety”. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 35 (2 Pt 2): S1–93. (April 2002). doi:10.1006/rtph.2002.1542. PMID 12180494.

- ^ a b “Aspartame”. UK FSA (2008年6月17日). 2012年2月21日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年9月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Aspartame”. EFSA. 2023年7月17日閲覧。

- ^ “Aspartame”. Health Canada (2002年11月5日). 2010年9月22日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年9月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b Kay O'Donnel (2012). Mitchell H. ed. Sweeteners and sugar alternatives in food technology. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 126

- ^ a b Rios-Leyvraz M, Montez J (12 April 2022). Health effects of the use of non-sugar sweeteners: a systematic review and meta-analysis (Report). WHO. hdl:10665/353064. ISBN 978-92-4-004642-9。

- ^ a b “Human receptors for sweet and umami taste”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (7): 4692–4696. (April 2002). Bibcode: 2002PNAS...99.4692L. doi:10.1073/pnas.072090199. PMC 123709. PMID 11917125.

- ^ 「代用甘味料の利用法」『e-ヘルスネット』 厚生労働省、2010年10月31日閲覧。(archive版)

- ^ a b c d e “Aspartame and Other Sweeteners in Food”. FDA (2023年7月14日). 2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Acute glycemic and insulinemic effects of low-energy sweeteners: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials”. Am J Clin Nutr . 2020 Oct 1;112(4):1002-1014. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa167.. 2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ “New Products Weigh In”. foodproductdesign.com. 2011年7月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年6月19日閲覧。

- ^ “栄養表示基準について” (2018年10月18日). 2023年7月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Is Aspartame Safe to Eat If You Have Diabetes?”. Healthline Media (2019年11月11日). 2023年7月19日閲覧。

- ^ “アミノ酸から生まれた、カラダにやさしい高甘味の甘味料”. 味の素株式会社. 2023年7月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b c G. G. Habermehl, P. E. Hammann, H. C. Krebs: Naturstoffchemie. Eine Einführung. 3. Auflage. Springer, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-540-73732-2, S. 307.

- ^ a b c J. N. Bergmann, W. Vetsch: Aspartam. In: Gert-Wolfhard von Rymon Lipinski (Hrsg.): Handbuch Süßungsmittel. Eigenschaften und Anwendung. Behr, Hamburg 1991, ISBN 3-925673-77-6.

- ^ Hans-Dieter Belitz, Werner Grosch, Peter Schieberle: Lehrbuch der Lebensmittelchemie. 6. Auflage Springer, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-540-73202-0, S. 453

- ^ Käte K. Glandorf, Peter Kuhnert, E. Lück: Handbuch Lebensmittelzusatzstoffe. Behr, Hamburg 1991, ISBN 978-3-925673-89-4, S. 12.

- ^ “How Sugar Substitutes Stack Up”. National Geographic News (2013年7月17日). 2019年2月22日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年2月21日閲覧。

- ^ “Sugar replacement in sweetened bakery goods”. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 49 (9): 1963–1976. (2014). doi:10.1111/ijfs.12617.

- ^ “New Products Weigh In”. foodproductdesign.com. 2011年7月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年6月19日閲覧。

- ^ a b c 商品ガイドブック―パルスイートカロリーゼロ、味の素

- ^ “Fountain Beverages in the US”. The Coca-Cola Company (2007年5月). 2009年3月20日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ WHO (1987). “Principles for the safety assessment of food additives and contaminants in food”. Environmental Health Criteria 70. オリジナルの30 April 2015時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ a b c d “日本食品添加物協会”. 日本食品添加物協会. 2020年6月25日閲覧。

- ^ a b “公開討論会「食の信頼向上をめざして〜食品安全委員会、消費者委員会のこれから」”. くらしとバイオプラザ21 (2009年10月6日). 2023年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae “甘味料アスパルテーム〝発がん性〟報道の真の意味”. Wedge(松永和紀 - 食品安全委員会委員) (2023年7月14日). 2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ a b EFSA Panel On Food Additives And Nutrient Sources Added To Food (10 December 2013). “Scientific Opinion on the re-evaluation of aspartame (E 951) as a food additive”. EFSA Journal 11 (12): 3496. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2013.3496. オリジナルの30 June 2023時点におけるアーカイブ。 2023年6月30日閲覧。.

- ^ a b “The intake of intense sweeteners – an update review”. Food Additives and Contaminants 23 (4): 327–338. (April 2006). doi:10.1080/02652030500442532. PMID 16546879. オリジナルの23 August 2022時点におけるアーカイブ。 2022年4月22日閲覧。.

- ^ “人工甘味料アスパルテームに発がんの可能性、WHOが初の見解”. CNN (2023年7月14日). 2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f “◆ アステルパームについて(「食品安全情報」から抜粋・編集) -欧州 EFSA(2005 年 7 月~2023 年 6 月)-” (PDF). 国立医薬品食品衛生研究所. 2023年7月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f “アスパルテームに関するQ&A”. 内閣府食品安全委員会 (2023年7月14日). 2023年7月17日閲覧。

- ^ “用語集検索(リスク評価)”. 食品安全委員会. 2023年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ “「ADI」と「TDI」” (PDF). 食品安全委員会. 2023年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ “食品安全の基礎知識と 食品添加物について” (PDF). 食品安全委員会 (2018年6月20日). 2023年6月16日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i “◆ アステルパームについて(「食品安全情報」から抜粋・編集) -WHO(2022 年 6 月~2023 年 7 月)-” (PDF). 国立医薬品食品衛生研究所. 2023年7月19日閲覧。

- ^ “An amino-acid taste receptor”. Nature 416 (6877): 199–202. (March 2002). Bibcode: 2002Natur.416..199N. doi:10.1038/nature726. PMID 11894099.

- ^ a b c d e f “Effect of sucralose and aspartame on glucose metabolism and gut hormones”. Nutrition Reviews 78 (9): 725–746. (September 2020). doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuz099. PMID 32065635.

- ^ “Simultaneous formation and detection of the reaction product of solid-state aspartame sweetener by FT-IR/DSC microscopic system”. Food Additives and Contaminants 17 (10): 821–827. (October 2000). doi:10.1080/026520300420385. PMID 11103265.

- ^ Oppermann JA, Muldoon E, Ranney RE. Effect of aspartame on phenylalanine metabolism in the monkey. J Nutr. 1973 Oct;103(10):1460-6. doi:10.1093/jn/103.10.1460. PMID 4200873.

- ^ Trefz F, de Sonneville L, Matthis P, Benninger C, Lanz-Englert B, Bickel H. Neuropsychological and biochemical investigations in heterozygotes for phenylketonuria during ingestion of high dose aspartame (a sweetener containing phenylalanine). Hum Genet. 1994 Apr;93(4):369-74. doi:10.1007/BF00201660. PMID 8168806.

- ^ “Comparative metabolism of aspartame in experimental animals and humans”. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 2023年7月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Sweeteners and sugar alternatives in food technology”. Blackwell. 2023年7月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Aspartame: review of safety”. Regulatory toxicology and pharmacology: RTP. 2023年7月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Phenylalanine”. PubChem, National Library of Medicine, US National Institutes of Health (2023年5月27日). 2023年4月22日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2023年6月2日閲覧。

- ^ FOOD ALLERGIES RARE BUT RISKY(1999年1月17日時点のアーカイブ)

- ^ “安心してお買い上げ下さい。安心してお使い下さい 。”. 味の素株式会社. 2023年7月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b “CFR – Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Part 172: Food additives permitted for direct addition to food for human consumption. Subpart I – Multipurpose Additives; Sec. 172.804 Aspartame”. US Food and Drug Administration (2018年4月1日). 2018年9月20日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年8月22日閲覧。

- ^ “Aspartame”. UK Food Standards Agency (2015年3月19日). 2017年7月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年6月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Mandatory Labelling of Sweeteners”. Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Health Canada (2018年5月11日). 2023年7月6日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年8月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b “パルスイート®、パルスイート®カロリーゼロってどういう商品?”. 味の素株式会社. 2023年7月17日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Henkel, John (1999). “Sugar Substitutes: Americans Opt for Sweetness and Lite”. FDA Consumer Magazine 33 (6): 12-6. PMID 10628311. オリジナルの2007年1月2日時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ “Endogenous production of methanol after the consumption of fruit”. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 21 (5): 939–43. (August 1997). PMID 9267548.

- ^ International Program on Chemical Safety (IPCS), 1997. アーカイブ 2015年4月28日 - ウェイバックマシン Environmental Health Criteria 196, Methanol. Published under the joint sponsorship of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, and the World Health Organization, and produced within the framework of the Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals.

- ^ Sweeteners and sugar alternatives in food technology. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. (2006). p. 94. ISBN 978-1-4051-3434-7

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j “◆ アステルパームについて(「食品安全情報」から抜粋・編集) -北米(2006 年 5 月~2023 年 5 月)-” (PDF). 国立医薬品食品衛生研究所. 2023年7月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies”. CMAJ 189 (28): E929–E939. (July 2017). doi:10.1503/cmaj.161390. PMC 5515645. PMID 28716847.

- ^ “Does low-energy sweetener consumption affect energy intake and body weight? A systematic review, including meta-analyses, of the evidence from human and animal studies”. International Journal of Obesity 40 (3): 381–394. (March 2016). doi:10.1038/ijo.2015.177. PMC 4786736. PMID 26365102.

- ^ “Low-calorie sweeteners and body weight and composition: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies”. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 100 (3): 765–777. (September 2014). doi:10.3945/ajcn.113.082826. PMC 4135487. PMID 24944060.

- ^ a b “Metabolic effects of aspartame in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials”. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 58 (12): 2068–2081. (April 2017). doi:10.1080/10408398.2017.1304358. PMID 28394643.

- ^ “Use of non-sugar sweeteners: WHO guideline”. WHO (2023年5月15日). 2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d “Diet sodas are not actually good for your diet, WHO guidance suggests”. Ars Technica (2023年5月16日). 2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “砂糖の食べ過ぎはだめ、甘味料も控えて WHOが掲げるビターな指針”. 朝日新聞 (2023年6月24日). 2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ “世界保健機関(WHO)、ガイドライン「成人及び児童の糖類摂取量」を発表”. 食品安全委員会 (2015年3月4日). 2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ “WHO advises not to use non-sugar sweeteners for weight control in newly released guideline”. WHO (2023年5月15日). 2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Timeline of Selected FDA Activities and Significant Events Addressing Aspartame”. US Food and Drug Administration (2023年5月30日). 2023年7月1日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2023年7月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Artificial sweeteners and cancer”. National Cancer Institute, US National Institutes of Health (2023年1月12日). 2015年12月8日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2023年7月1日閲覧。

- ^ “Aspartame, low-calorie sweeteners and disease: regulatory safety and epidemiological issues”. Food and Chemical Toxicology 60: 109–115. (October 2013). doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.07.040. PMID 23891579.

- ^ “Aspartame: A review of genotoxicity data”. Food and Chemical Toxicology 84: 161–168. (October 2015). doi:10.1016/j.fct.2015.08.021. PMID 26321723.

- ^ Haighton, Lois; Roberts, Ashley; Jonaitis, Tomas; Lynch, Barry (1 April 2019). “Evaluation of aspartame cancer epidemiology studies based on quality appraisal criteria” (英語). Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 103: 352–362. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2019.01.033. ISSN 0273-2300. オリジナルの29 June 2023時点におけるアーカイブ。 2023年6月29日閲覧。.

- ^ Soffritti, M.; Belpoggi, F.; Esposti, D.D. et al. (2006). “First Experimental Demonstration of the Multipotential Carcinogenic Effects of Aspartame Administered in the Feed to Sprague-Dawley Rats”. Environ Health Perspect 114 (3): 379–385. doi:10.1289/ehp.8711. PMC 1392232. PMID 16507461.

- ^ Soffritti, M.; Belpoggi, F.; Tibaldi, E.; Esposti, D.D.; Lauriola, M. (2007). “Life-span exposure to low doses of aspartame beginning during prenatal life increases cancer effects in rats”. Environ Health Perspect 115 (9): 1293–1297. doi:10.1289/ehp.10271. PMC 1964906. PMID 17805418.

- ^ Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (2006). “Opinion of the Scientific Panel on food additives, flavourings, processing aids and materials in contact with food (AFC) related to a new long-term carcinogenicity study on aspartame”. The EFSA Journal 356 (5): 1–44. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2006.356.

- ^ “US FDA/CFSAN – FDA Statement on European Aspartame Study”. Food and Drug Administration (2007年4月20日). 2010年9月23日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年9月23日閲覧。

- ^ Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (2009). “Updated opinion on a request from the European Commission related to the 2nd ERF carcinogenicity study on aspartame, taking into consideration study data submitted by the Ramazzini Foundation in February 2009”. The EFSA Journal 1015 (4): 1–18. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2009.1015.

- ^ “Health Canada Comments on the Recent Study Relating to the Safety of Aspartame”. Health Canada (2005年7月18日). 2011年2月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Statement on a Carcinogenicity Study of Aspartame by the European Ramazzini Foundation”. Committee on Carcinogenicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment. 2011年2月28日閲覧。

- ^ “Aspartame: a safety evaluation based on current use levels, regulations, and toxicological and epidemiological studies”. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 37 (8): 629–727. (2007). doi:10.1080/10408440701516184. PMID 17828671. "これには、「飼料『コルチセラ』の組成とアスパルテームの添加方法が特定されておらず、栄養不足の可能性があること」「アスパルテームの保管条件と取り扱いが特定されていないことによる汚染の問題」「いくつかの業界標準の無視(動物の無作為化の欠如、入手しやすい病原体を持たない動物とは対照的に病原体を保有する研究所の無作為交配系統の使用。死亡時の年齢にばらつきがある終生動物の使用とそれらの動物を若い対照動物と比較すること。高密度飼育と異なる動物群を異なる条件で飼育することを含む)」「リンパ系新生物や他の病変をより早く、高い割合で引き起こすことが知られている交絡感染症の異常な高発生率」「誘発された腫瘍は『自然に発生する腫瘍と区別することができ、区別すべきである』という研究があるにもかかわらず、異なる組織型からの腫瘍(リンパ腫および白血病)のプール」「複数の領域における不十分/不完全/矛盾した方法論とデータ収集/報告」。また、「 ERFは過形成を悪性腫瘍と誤診していた」というアメリカ国家毒性プログラムの調査結果もある。Magnusonは、ERFの研究デザインおよび実施上の問題と合わせて、この研究はアスパルテームの発がん性を示す信頼できる証拠にはならないと結論づけた。"

- ^ Lofstedt, Ragnar E (2008). “Risk Communication, Media Amplification and the Aspartame Scare”. Risk Management 10 (4): 257–284. doi:10.1057/rm.2008.11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h 『栄養と料理2023年5月号』女子栄養大学出版部、2023年4月7日、103-107(佐々木敏がズバリ読む栄養データ 人工甘味料はがんを増やすか?フランスでの研究の読み方を考える)頁。

- ^ a b “Artificial sweeteners and cancer risk: Results from the NutriNet-Santé population-based cohort study”. PloS Medicine (2022年3月24日). 2023年7月17日閲覧。

- ^ “Künstliche Süßstoffe steigern Krebsrisiko”. ORF ON Science (2022年3月26日). 2023年7月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b “甘味料摂取とがんリスクとの関係に関する論文への懸念”. 今村文昭博士(ケンブリッジ大学Senior Investigator Scientist) (2023年7月3日). 2023年7月17日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d “FDA says soda sweetener aspartame is safe, disagreeing with WHO finding on possible cancer link”. CNBC (2023年7月14日). 2023年7月18日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “食品安全情報(化学物質)No. 15/ 2023(2023. 07. 19)” (PDF). 国立医薬品食品衛生研究所 安全情報部 (2023年7月19日). 2023年7月25日閲覧。

- ^ a b “アスパルテームの発がん性分類、その意味は? 日本人の摂取は微量”. 朝日新聞 (2023年7月14日). 2023年7月19日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “Aspartame hazard and risk assessment results released (news release)”. World Health Organization (2023年7月13日). 2023年7月14日閲覧。

- ^ “Aspartame hazard and risk assessment results released”. WHO (2023年7月14日). 2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Carcinogenicity of aspartame, methyleugenol, and isoeugenol”. The Lancet Oncology. (2023). doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00341-8.

- ^ “What To Know About Aspartame: The Sugar Substitute In Diet Coke Declared As A Possible Cancer Risk By WHO”. forbes (2023年7月14日). 2023年7月19日閲覧。

- ^ Naddaf, Miryam (14 July 2023). “Aspartame is a possible carcinogen: the science behind the decision”. Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02306-0.

- ^ “人工甘味料アスパルテーム、国際研究機関が発がん可能性リスト掲載へ(字幕・29日)”. ロイター (2023年6月30日). 2023年7月1日閲覧。

- ^ a b “国際がん研究機関(IARC)による加工肉及びレッドミートの発がん性分類評価について”. 農林水産省 (2015年12月1日). 2023年7月17日閲覧。

- ^ “国際がん研究機関(IARC)によるコーヒー、マテ茶及び非常に熱い飲料の発がん性分類評価について”. 農林水産省 (2016年6月16日). 2023年7月17日閲覧。

- ^ a b c “国際がん研究機関(IARC)の概要とIARC発がん性分類について”. 農林水産省 (2023年7月13日). 2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ “Why the aspartame in Diet Coke and Coke Zero probably isn’t worth worrying about”. statnews (2023年7月8日). 2023年7月15日閲覧。

- ^ “'Inactive' ingredients in pharmaceutical products: update (subject review). American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs”. Pediatrics 99 (2): 268–278. (February 1997). doi:10.1542/peds.99.2.268. PMID 9024461.

- ^ “Foods and supplements in the management of migraine headaches”. The Clinical Journal of Pain 25 (5): 446–452. (June 2009). doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31819a6f65. PMID 19454881.

- ^ “◆ アステルパームについて(「食品安全情報」から抜粋・編集) -欧州諸国(2003 年 4 月~2023 年 6 月)-” (PDF). 国立医薬品食品衛生研究所. 2023年7月19日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Commercial, Synthetic Non-nutritive Sweeteners”. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 37 (13–24): 1802–8117. (1998). doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980803)37:13/14<1802::AID-ANIE1802>3.0.CO;2-9.

- ^ a b c d US 20040137559, "Process for producing N-formylamino acid and use thereof", issued 2003-10-20

- ^ “The Saccharin Saga – Part 6”. ChemViews Magazine (2016年4月5日). 2018年6月2日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2019年3月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Synthesis and application of dipeptides; current status and perspectives”. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 81 (1): 13–22. (November 2008). doi:10.1007/s00253-008-1590-3. PMID 18795289.

- ^ a b c “Aspartic acid-based sweeteners”. Symposium: sweeteners. Westport, CT: AVI Publishing. (1974). pp. 159–63. ISBN 978-0-87055-153-6. LCCN 73--94092

- ^ Discovery: windows on the life sciences. Oxford: Blackwell Science. (2001). p. 4. ISBN 978-0-632-04452-8

- ^ 中村圭寛「ダイエット甘味料アスパルテーム」『日本醸造協会誌』第86巻第3号、日本醸造協会、1991年、200-207頁、doi:10.6013/jbrewsocjapan1988.86.200、ISSN 0914-7314、NAID 130004305518。

- ^ “Torunn A. Garin, 54, Noted Food Engineer”. The New York Times. (2002年5月1日). オリジナルの2016年3月6日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b c d e f “How Sweet Is It?”. 60 Minutes. (1996年12月29日)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i “Food additive approval process followed for Aspartame”. US Food and Drug Administration (1987年6月18日). 2022年10月9日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2022年7月14日閲覧。

- ^ Testimony of Dr. Adrian Gross, Former FDA Investigator to the US Senate Committee on Labor and Human Resources, 3 November 1987. Hearing title: "NutraSweet Health and Safety Concerns." Document # Y 4.L 11/4:S.HR6.100, pp. 430–39.

- ^ a b “About Equal ®”. Equal.com (2006年). 2010年11月22日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2022年7月14日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Historical information”. Canderel – For a Healthy Balanced Lifestyle that Tastes as Good as Sugar. Diet, sweetener, recipes.. 2007年2月3日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2022年7月14日閲覧。

- ^ FDA Statement on Aspartame, 18 November 1996|access-date=14 July 2022

- ^ Merisant – About Merisant – The History of Equal and Canderel Archived August 29, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (2006). “Opinion of the Scientific Panel on food additives, flavourings, processing aids and materials in contact with food (AFC) related to a new long-term carcinogenicity study on aspartame”. The EFSA Journal 356 (5): 1–44. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2006.356.

- ^ FSA Determining reactions to aspartame in subjects who have reported symptoms in the past compared to controls: a pilot double blind crossover study Archived 2014-03-05 at the Wayback Machine. Last updated on 17 February 2010

- ^ a b http://cot.food.gov.uk/pdfs/cotposponaspar.pdf FSA Committee on Toxicity. [Position Paper on a Double Blind Randomized Crossover Study of Aspartame Archived March 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ “EFSA Call: Call for scientific data on Aspartame (E 951)”. efsa.europa.eu (2011年). 2011年11月25日閲覧。

- ^ “EFSA makes aspartame studies available”. Food Navigator (2011年). 2011年11月25日閲覧。

- ^ “EFSA delay Aspartame review findings until 2013”. foodnavigator.com (2012年8月8日). 2012年8月22日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2012年8月14日閲覧。

- ^ a b “EFSA Press Release January 8, 2013”. 2015年8月17日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2013年1月26日閲覧。

- ^ “EU launches public consultation on sweetener aspartame”. AFP. (2013年1月8日). オリジナルの2014年1月31日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2013年1月30日閲覧。

- ^ “食品添加物に関する 日本生協連の取り組み” (PDF). 日本生活協同組合連合会 (2010年11月4日). 2023年7月21日閲覧。

- ^ “コンシューマーズカフェレポート「今、消費者に求められていること〜振り返りの中から」”. くらしとバイオプラザ21 (2011年5月24日). 2023年7月21日閲覧。

- ^ “コープ自然派は、食品添加物にも厳しい独自基準を設けています”. コープ自然派. 2023年7月21日閲覧。

- ^ “パルシステムは甘味料を使っていますか?”. パルシステム (2021年7月9日). 2023年7月21日閲覧。

- ^ “要注意食品添加物リスト12” (PDF). 生活クラブ. 2023年7月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Martin, Michael J. C. (September 16, 1994). Managing Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Technology-based Firms. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 18–22. ISBN 978-0471572190

- ^ a b “Monsanto to Acquire G.D. Searle”. The New York Times. (1985年7月18日). オリジナルの2017年11月26日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b J.W. Childs Equity Partners II, L.P Archived 14 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine., Food & Drink Weekly, 5 June 2000

- ^ a b c “Ajinomoto May Exceed Full-Year Forecasts on Amino Acid Products”. Bloomberg L.P.access-date=23 June 2010. (2004年11月18日). オリジナルの2013年6月20日時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ “Aspartame ‘possibly’ carcinogenic, yet safe at common-use levels, WHO says”. The Japan Times (2023年7月14日). 2023年7月18日閲覧。

- ^ Shapiro, Eben (1989年11月19日). “Nutrasweet's Bitter Fight”. New York Times. オリジナルの2017年2月10日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2017年9月29日閲覧。

- ^ a b c ドナルド・ラムズフェルド(江口泰子、月沢李歌子、島田楓子:訳)『真珠湾からバグダッドへ ラムズフェルド回想録』幻冬舎、2012年、p.300-315

- ^ “JW Childs Acquires Monsanto's NutraSweet Sweetener Business”. Chemical Online (2000年3月28日). 2022年1月21日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2023年7月1日閲覧。

- ^ O'Donnell K (2006). "6 Aspartame and Neotame". In Mitchell HL (ed.). Sweeteners and sugar alternatives in food technology. Blackwell. pp. 86–95. ISBN 978-1-4051-3434-7.

- ^ 甘味料、発明対価1億8900万円 味の素特許訴訟判決 - 京都新聞、2004年2月24日。(2005年3月12日時点のアーカイブ)

- ^ “Sweetener sale-05/06/2000-ECN”. icis.com. 2011年7月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年7月9日閲覧。

- ^ “Monsanto Co. sold the last of its...”. Los Angeles Times (2000年5月31日). 2023年7月17日閲覧。

- ^ “Asda becomes first supermarket to axe all artificial flavourings and colours in own brand foods”. Evening Standard. (2012年4月12日). オリジナルの2022年10月23日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2022年10月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b Howard, Stephen (2009年7月15日). “Asda wins fight over 'nasty' sweetener”. The Independent. Press Association. オリジナルの2022年10月23日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2022年10月23日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Asda claims victory in aspartame 'nasty' case”. foodanddrinkeurope.com. 2010年1月3日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年6月23日閲覧。

- ^ Watson, Elaine (2010年6月2日). “Radical new twist in Ajinomoto vs Asda 'nasty' battle”. confectionery news (William Reed Ltd). オリジナルの2022年10月23日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2022年10月23日閲覧。

- ^ “FoodBev.com” (2010年6月3日). 2011年7月11日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年6月23日閲覧。 “Court of Appeal rules in Ajinomoto/Asda aspartame case”

- ^ “Asda settles 'nasty' aspartame legal battle with Ajinomoto”. FoodNavigator.com (William Reed Ltd). (2011年5月18日). オリジナルの2011年7月31日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2011年7月18日閲覧。

- ^ Bouckley, Ben (2011年5月16日). “Asda settles 'nasty' legal spat with Ajinomoto over sweetener aspartame”. foodmanufacture.co.uk (William Reed Ltd). オリジナルの2022年10月23日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2022年10月23日閲覧。

- ^ “FDA Approves New No-Calorie Sweetener”. Medscape. (2014年5月21日) 2014年5月22日閲覧。

- ^ “Food Additives & Ingredients - Additional Information about High-Intensity Sweeteners Permitted for Use in Food in the United States”. 2014年5月24日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2018年1月14日閲覧。

- ^ 味の素(株)の新甘味料「アドバンテーム」欧州と米国で食品添加物認可を取得、2014年5月27日、味の素、2017年10月8日閲覧

- ^ 味の素/新甘味料「アドバンテーム」、日本でも認可取得、2014年6月18日、2017年10月8日閲覧

- ^ Sugarman, Carole (1983年7月3日). “Controversy Surrounds Sweetener”. Washington Post: pp. D1–2. オリジナルの2011年6月29日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2008年11月25日閲覧。

- ^ “Six Former HHS Employees' Involvement in Aspartame's Approval GAO/HRD-86-109BR”. United States General Accounting Office (1986年7月). 2017年7月21日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2006年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e “Aspartame Warning, part 1. Netlore Archive: Email alert warns of serious health hazards attributed to the artificial sweetener aspartame” (1999年1月6日). 2023年7月18日閲覧。

- ^ “Should You Sour on Aspartame?”. Tufts University Health and Nutrition Letter. 2010年12月24日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2011年2月4日閲覧。

- ^ Warner, Melanie (2006年2月12日). “The Lowdown on Sweet”. The New York Times

- ^ Lawrence, Felicity (2005年12月15日). “Safety of artificial sweetener called into question by MP”. The Guardian

- ^ a b Kotsonis, Frank; Mackey, Maureen (2002). Nutritional toxicology (2nd ed.). p. 299. ISBN 978-0-203-36144-3

- ^ “Aspartame Information replies to the New York Times”. Aspartame Information Service (2006年2月16日). 2013年4月12日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年12月8日閲覧。

- ^ Flaherty, Megan (1999年4月12日). “Harvesting Kidneys and other Urban Legends”. NurseWeek. オリジナルの2012年8月22日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2013年3月7日閲覧。

- ^ a b c the University of Hawaii. “Falsifications and Facts about Aspartame – An analysis of the origins of aspartame disinformation”. 2012年2月17日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2008年12月8日閲覧。

- ^ “A Web of Deceit”. Time. (1999-02-08). オリジナルのJanuary 29, 2009時点におけるアーカイブ。 2009年1月19日閲覧. "In this and similar cases, all the Nancy Markles of the world have to do to fabricate a health rumor is post it in some Usenet news groups and let ordinary folks, who may already distrust artificial products, forward it to all their friends and e-mail pals."

- ^ “Aspartame Warning: Part 2: A Laundry List of Maladies” 2023年7月18日閲覧. "First off...this text was not written by "Nancy Markle"—whoever that may be. Its real author was one Betty Martini, who posted a host of similar messages to Usenet newsgroups in late 1995 and early 1996."

- ^ “Examining the Safety of Aspartame”. Multiple Sclerosis Foundation. 2010年11月29日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2014年12月12日閲覧。

- ^ a b Kiss My Aspartame Archived 2022-01-14 at the Wayback Machine.. False. Snopes.com, David G. Hattan,David Hattan, LinkedIn Acting Director, Division of Health Effects Evaluation, 8 June 2015

- ^ a b c “Deconstructing Web Pages – Teaching Backgrounder”. Media Awareness Network. 2014年12月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2014年12月12日閲覧。 – An exercise in deconstructing a web page to determine its credibility as a source of information, using the aspartame controversy as the example.

- ^ Zehetner, Anthony; McLean, Mark (1999). “Aspartame and the inter net”. The Lancet 354 (9172): 78. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)75350-2. PMID 10406399.

- ^ Condor, Bob (1999年4月11日). “Aspartame debate raises questions of nutrition”. Chicago Tribune. オリジナルの2013年3月14日時点におけるアーカイブ。 2013年1月19日閲覧。

- ^ Newton, Michael (2004). The encyclopedia of high-tech crime and crime-fighting. Infobase Publishing. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-0-8160-4979-0

- ^ a b Dean Edell, "Beware The E-Mail Hoax: The Evils Of Nutrasweet (Aspartame)", HealthCentral December 18, 1998

- ^ a b 『週刊金曜日』編集部:編『買ってはいけない (『週刊金曜日』別冊ブックレット2)』金曜日、1999年5月20日。

- ^ “買ってはいけない”. 週刊金曜日. 2023年7月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d 松永和紀『メディア・バイアス――あやしい健康情報とニセ科学』光文社〈光文社新書 298〉、2007年4月。ISBN 978-4-334-03398-9。

- ^ と学会『トンデモ本の世界R』太田出版、2001年10月、20-26頁。ISBN 4-87233-608-9。

- ^ a b 日垣隆『それは違う!』文藝春秋、2001年12月1日。ISBN 978-4167655020。

- ^ “人工甘味料アステルパームはバクテリアの糞。虫歯にならない代わりに癌になる。”. APTブログ. 2023年7月13日閲覧。

アスパルテームと同じ種類の言葉

| 甘味料に関連する言葉 | アスパルテーム カップリングシュガー(カップリングシュガ) 楓糖(ふうとう) |

- アスパルテームのページへのリンク