Seven years ago, Dr Charles Runels’ lover surprised him at his office, demanding that he inject blood into her clitoris as a Valentine’s Day present. She hiked up her dress, hopped on to the exam table and motioned for Runels to put on his headlamp. She explained that she’d been watching him inject his own penis with blood for about a year, and that while his bigger and stronger erections had been fun, she’d grown tired of the one-sided sexual enhancement. It was her turn. So Runels bowed between her legs, numbed her clitoris with an ice cube and shot her up.

“I don’t know how graphic you can be with this thing,” he said over the phone, pausing mid-story to ask me about the Guardian’s policy on discussing orgasms. “But the next afternoon, she came to see me, and her orgasms came more quickly – very strong, ejaculatory orgasms. The passion, the thunder, the sounds that she was making …”

He sighed at the memory.

“That’s when I thought: I should try this on my patients.”

And just like that, the O-Shot was born.

The non-surgical treatment that aims to facilitate and improve orgasms in women, which Runels trademarked in 2011, can only be performed by him or one of the more than 500 certified practitioners he’s trained over the years. It has two steps: first, he extracts PRP, or platelet-rich plasma, from a woman’s blood (usually taken from her arm). He then re-inserts it into the clitoris and the ceiling of her vagina with a syringe. The infusion of white blood cells, according to Runels, increases lubrication and sensitivity, allowing the patient to reach climax easily.

Today, more than 20,000 women have had the procedure done, and Runels estimates an 85% success rate. In the mainstream medical community, however, the O-Shot is controversial; its findings are viewed as inadequately tested (it’s not FDA approved) and some question whether its effects boil down to nothing more than placebo.

But Runels insists the procedure changes lives. He also claims it can cure incontinence and pain during sex caused by anything ranging from scarring after childbirth, to post-radiation dryness and even female genital mutilation (FGM). For Runels, the ability to have good orgasms “empowers” assault victims and is essential to a woman’s “overall wellbeing”.

In others words, this is a man obsessed with making women come.

As I listened to him describe the procedure and his philosophy, I wondered: who was this man who’d dedicated so much of his life to helping women orgasm? What was behind Runels’ fixation? Was he a feminist revolutionary? Or a total creep?

I booked a flight to Alabama to find out.

Fairhope, Alabama (population 5,326) is an unlikely place to find a man trying to revolutionize women’s sexual health. Runels admits that living “in the buckle of the Bible belt” – where vibrators are literally illegal, thanks to the state’s Anti-Obscenity Enforcement Act – poses certain drawbacks.

“But as long as you’re not too open about it, you can find the free-thinking people,” he said.

Still, peddling clit injections seemed like a hard sell.

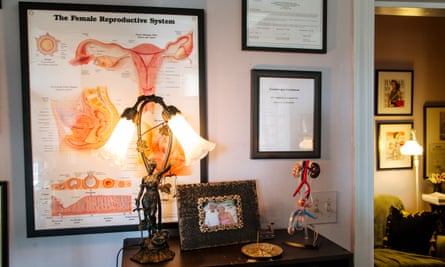

Runels’ office isn’t anything like the sterile exam rooms most women associate with gynecological exams. It’s intimate, personal and cozy – because in addition to treating thousands of patients there over the years, he also lives there. The small entryway opens on to a living room dominated by gym equipment. In the bathroom, I found a functioning shower and shelves filled with employees’ toiletries. The only examination table was separated from the kitchen by a curtain.

Pamela, Julie and Vivienne – the three women on Runels’ four-person staff – greeted me with open arms. In order to better understand what they promoted, Pamela and Vivienne told me they’d both had O-Shots administered by Runels. (Mark, the sole male employee, opted for the male version, a “P-Shot”.)

When I asked whether it was weird for any of them that their employer had seen their genitals, they laughed: “Of course not!” Pamela had never felt better; she said she enjoyed multiple orgasms now. She called Runels’ work “a miracle – the intersection between God and science”.

As we awaited the arrival of my first interview subject, Lacey, Runels suggested that I might want to try the O-Shot for myself. “You’ll love it,” Vivienne said. She told me that doctors regularly flew in from all over the world to be trained in the procedure, and that initially they reacted to offers of free O-Shots just as I had – with a mix of embarrassment and surprise. But by the end, she said, everyone wanted one.

She and Runels laughed, recalling how the last class had run until three in the morning, just to accommodate demand. “It’s like a Baptist revival, except you’re injecting each other’s genitals,” he said.

I assured them I wasn’t interested. Runels looked at me and said: “Don’t be surprised if you change your mind.”

Throughout this piece, I’ve changed O-Shot recipients’ names – including those of Runels’ employees – in order to protect their identities. Many live in the small, Christian community of Fairhope and fear ostracism. Others have suffered sexual trauma, and fear being the targets of further abuse.

Lacey, an athletic, 40-year-old businesswoman, told no one when she was raped for the first time at age 13. But soon her father “noticed something different” about her and started calling her a “whore and a lesbian”. Physical abuse followed when Lacey’s next rapist, her husband, found himself unable to climax unless Lacey was in excruciating pain. He raped her throughout their 10-year relationship, and left her with herpes, incontinence and vaginal scarring.

At 29 years old, she wet the bed, had never had an orgasm and thought her vagina was deformed. Doctors responded to her concerns by suggesting lube and psychotherapy.

At 30, Lacey never expected to experience sexual pleasure again. She tried using a back massager for stimulus, but it left a painful callous on her clitoris. Later she met Runels at the bank where she worked. After learning what he did, she confided in him, and Runels said he knew of something that might help – or, at the very least, something that would not hurt her.

Lacey got the O-Shot on her lunch break, and immediately “felt alive down there”. Over the next few weeks the callous slowly disappeared, revealing healthy, circulated tissue. Her incontinence went away.

But more than anything, Lacey felt healed by her newfound ability to orgasm; before the shot, climaxing, if it happened at all, had taken about half an hour of “jackhammering friction”. After the shot, she switched to a gentle (and illegal – remember, this is Alabama) finger vibrator, and came within seconds. She told me that better orgasms improved her mood, her self-image, her career and her dating life.

“Having pleasure, especially predictable pleasure, is empowering as a woman,” she said.

Like Runels’ employees, and most of the other patients I spoke to, Lacey described herself as “church-going”. She said that as a Christian it felt uncomfortable to talk about sex, much less orgasms, but that she’d never have learned to love herself if she hadn’t been able to climax, and she wanted women to know that there were non-invasive medical procedures available that could help them with what most doctors might dismiss as purely mental.

Over the next few days, I would speak at length with Runels’ staff and patients, as well as with O-Shot practitioners and recipients from around the globe, all of whom said the O-Shot cured incontinence, reduced vaginal scarring, and improved sensation, lubrication and quality of life.

One Brooklyn-based gynecologist, Dr Sophia Lubin, who worked with Somalian refugees, said that, unfortunately, misapprehensions about the procedure produced huge barriers to entry – “People don’t want further trauma, and, even if it doesn’t hurt, the needle in the vagina is a scary thing, especially for people who’ve been raped or harmed” – but suggested that based on her experience with other patients, the O-Shot posed enormously positive implications for victims of FGM.

Had all these people really been swayed by placebo?

In general, O-Shot providers I spoke with estimated an 85% success rate for their patients. “But on Lacey, it worked dramatically,” Runels said, “and even if that’s one in 100, it’s worth pursuing.” He desperately needed me to understand the importance of her turnaround. “That’s my revenge [against rapists] – to say ‘Eff you’ and give women their flower back.”

I spoke to his patients, employees and former lovers, many of whom also happened to be targets of sexual assault. I couldn’t help thinking Runels seemed to gravitate toward victims of trauma. “I don’t really know why I’m surrounded by people who have pain,” he admitted. “I do, absolutely, make a conscious effort [to find them]. I think my real usefulness evolves out of … it’s not even compassion, it’s more like obsession.”

When I asked him whether he thought he might have some kind of savior complex, he grew quiet, anxiously massaging the skin where his eyebrows should have been. Runels is bald, with zero eyebrows. Initially, I read his hairlessness as a possible extension of his sexual persona – like, maybe he shaved his entire body.

But the true story behind his baldness proved much more complicated, and started with every teenager’s worst nightmare: severe cystic acne. He did not have pimples; he had oozing, volcanic skin that piled up on itself. Individual features disappeared. He forgot what his nose looked like. “If you could make me attractive,” he prayed into the mirror, “I will find something good to do with it.”

Heaven sort of answered when dermatologists offered to treat his skin with X-rays. The cystic acne popped, scabbed and fell away. But there were consequences.

By the time I showed up in Alabama, he’d undergone three months of semi-successful chemotherapy treatments for melanomas that had cropped up from the radiation. The worst one, which I’d initially mistaken for a beauty mark, had gotten smaller, but he still might need his upper lip removed.

“I can’t really promote [the cosmetic side of my practice] if I look like a monster,” he conceded.

He confessed that his work in women’s sexual health was probably tied to his personal experience with enduring a condition that made others uncomfortable – “that pain of what I call the hidden population”.

“Only 14% of women in their whole lifetime will ever have a conversation with their doctor about sex,” he said, “and if she brings up the subject, most times the doctor will change the subject after the first question. It’s time for us to quit avoiding the subject of a woman’s sexual function, and actually start thinking about how the system of her sexuality might work.”

Wasn’t it strange, he wondered, that when it came to a woman’s health, we talked about her body only in terms of a reproductive system?

He gestured to the plastic female pelvis on his bookshelf. “What about an orgasm system?” he said.

As someone who enjoys orgasms, I agree with Runels that they’re “important”, but I’m not a scientist. So I set out to fact-check his claim that orgasms help women feel better (and the implied reverse claim: that the absence of orgasms counts as sexual dysfunction) against what we already know.

But it turns that we don’t know very much.

I mined academic periodicals for information on the interplay between orgasms and health. But as far as I could tell, such studies tended to center on male sexual dysfunction in the wake of prostate cancer. It seemed like scientists were eager to investigate the devastating effects of surgery on a man’s inability to ejaculate, while a female cancer survivors’ sexuality only mattered in terms of whether she could still have children.

Disgruntled by the academic definition of women’s health as “cancer” or “babies”, I extended my search to female orgasms in general, and I found that research devoted to the subject often revolved around questions such as – and I’m paraphrasing here – “Is female ejaculation a real thing?” or “Why does the female orgasm even exist?”

As for how orgasms (or the lack thereof) might relate to a woman’s health or happiness? Academics aren’t interested.

Many in the mainstream medical community see the O-Shot as little more than a placebo.

When I asked Dr Jennifer Gunter, an OB/GYN who writes frequently about female sexuality, what she thought about Runels and his techniques, she screamed.

“You don’t do procedures on partners! I want to vomit,” she said. “You’re not supposed to practice medicine on your family and friends … oh my God. Talk about a power differential.”

Though some hail the O-Shot as a much-needed advancement in women’s sexual health, many doctors are skeptical of Runels – and his methods. Gunter told me that Runels’ close relationships with some O-Shot recipients enhanced the likelihood of placebo – that, whether or not they knew it, these women wanted Runels to feel good about himself.

She explained that in order to take the O-Shot seriously, she’d first want to see somebody do a study on “10 rat vaginas”. She pointed out that Runels’ procedure had not yet been approved by the FDA, and compared the potential unknown side-effects to those that might be associated with the unregulated use of a vaginal mesh.

She laughed. “To get something approved by the FDA is a very low bar. You basically have to prove you didn’t kill 20 people – I mean, I don’t know what it was, exactly. [But] the body can do really weird crazy things. You can’t predict.”

When I explained that Runels had actually spent about a year injecting his own penis with blood before shooting up his first clitoris, Gunter laughed. “If people want to do whatever with their own body, have at it. But an untested procedure on your sexual partners?”

As as I could tell, the word “untested” seemed up for debate – according to Runels, it had been tested; using funds from his medical group, Runels had recently financed a $95,000 study to test the effect of the O-Shot on vulvar lichen sclerosus, a dermatological, eczema-like condition which produces cracking and bleeding around the vagina, led by George Washington University faculty member and lichen sclerosus expert Dr Andrew Goldstein.

According to Runels, the results of the study suggest that PRP injections decrease inflammation in women with vulvar lichen sclerosus. (This paper has since been published in the Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease.)

Gunter, who specialized in lichen sclerosus and had previously warred with Runels on Twitter, said she’d seen the paper but couldn’t take it seriously, since it only involved nine participants – “It’s a case series, not a study” – not to mention that the overall absence of a placebo group ruined its findings. When I asked Gunter what she thought about the participants’ feedback, which was apparently positive, she explained to me the difference between actual evidence (numbers) and anecdotal evidence (human testimony).

I had trouble with the idea that a woman’s feedback was purely anecdotal. Didn’t dismissing a woman’s sexuality as a psychological issue implicitly throw into question her ability to describe what was happening to her body?

Gunter countered that the dermatological issues associated with lichen sclerosus were categorically separate from sexual function. She had patients “in their 50s, 60s” with lichen sclerosus who didn’t even care about sex “because their husbands were impotent”.

I flinched at this. Wasn’t it sort of a double standard to say that if man can’t get erection, he’s “impotent” – in other words: he has sexual dysfunction whether he wants it or not, but a woman only has it if it bothers her?

Why did diagnoses of sexual dysfunction appear to be split along gender lines, considered either physical or psychosomatic depending on the presence or absence of an erection?

Gunter sighed. Apparently I was conflating two separate fields. She urged me to run some of the scenarios I’d mentioned (injecting lovers, injecting employees) by a bioethics expert.

So I contacted Tim Caulfield, a professor at the University of Alberta’s school of law and school of public health.

Caulfield told me that PRP first became “sexy” in 2013, when NBA players such as Kobe Bryant started getting the injections to heal athletic injuries. That same year, blood injections rocketed into the world of trendy cosmetics when doctors in Miami gave Kim Kardashian a “vampire facelift” (another of Runels’ trademarked PRP procedures, it turns out, where blood is dripped all over the T-zone while attacking the area with needles).

Afterward, Kardashian posted a selfie of her blood-soaked face (when the photo went viral, her doctor received an official “cease and desist” call from Runels, who explained he owned the trademark). But despite its popularity in mainstream media, Caulfield said that the actual science behind PRP was “iffy” at best.

Like Gunter, he brought up the placebo effect – and, in particular, “placebo theater”. He explained that white coats, medical lingo and especially the presence of needles combine to heighten a patient’s anticipation that a treatment will work.

The O-Shot ranged in price from $1,200-$1,500, and controlled studies have shown that more costly treatments increased the placebo effect – an effect that is so strong, it has been shown to actually create physical improvement in Parkinson’s symptoms.

Was my kneejerk reaction to stand up for Runels predicated on subconscious insecurity? As a journalist, did I need to believe so badly that I’d come to Fairhope for a reason – that I’d not been lured in by a campaign for snake oil – that I was refusing to entertain reason?

Later during my visit to Runels’ clinic, I was sitting down for lunch – idly asking him why he’d trademarked the name of his procedures – when suddenly he stabbed a giant needle through the lid of my sushi container.

“That,” he said, gesturing theatrically at my impaled take-out box, “is why I trademark my ideas.” He explained that an individual claiming to administer the O-Shot had once stuck “a mixing needle” – which is about the size of a cocktail spear, and should only be used to pierce rubber – into a woman’s clitoris, endangering her physical safety.

Owning the O-Shot name enabled Runels to mine the term online, ensuring that practitioners who offered it had trained with him. Runels paid his lawyer $30,000-$50,000 a month just to track down and send cease-and-desist letters to anyone who advertised the O-Shot without having trained with Runels or someone in his medical group.

Two of Runels’ assistants, Pamela and Julie, entered to tell me Julie would be getting the O-Shot – right then – so I could witness how painless it was. Julie explained that this wasn’t just for my benefit – that she was 50 years old, had suffered incontinence since having kids and was hoping the O-Shot would help. So I put away my sushi and followed her through the curtain. Moments later, in an awkward attempt to make conversation while I sat between her legs, I said: “Your vagina looks like my vagina.”

“Oh, good,” Julie said, sounding relieved as she glanced down at her lap. She lay back, clutching Pamela’s hand, explaining that she’d always secretly thought that she might be “deformed down there”.

“Everyone comes here thinking that,” Pamela reassured her.

Runels hummed his way into the room and after drawing blood from Julie’s arm, he loaded it into the centrifuge and left us alone so that Pamela could lather on the numbing cream. She used her fingers to spread Julie’s labia, gently coaxed the clitoris from its hood and applied the ointment. After giving it time to kick in, Runels returned to inject the lidocaine into the top crest of Julie’s labia minora – at the point just before it branched into the base of the clitoris.

I waited for Julie to cry out in pain. But instead she just kept talking to Pamela about church. Runels explained to me that this area of the labia wasn’t sensitive (it was built to rip during childbirth) and that bloodflow would naturally take the lidocaine from the labia minora into the clitoris, making a direct injection unnecessary. We made small talk for a few minutes until she she was fully numb. Then Runels plucked the vial of her blood from the centrifuge, preparing for the final injection – a direct hit to the clit. The PRP floated on top, yellow and opaque, like dehydrated urine.

While Runels flicked the needle, I ignored the taste of metal in my mouth, squeezed my thighs together and pretended everything was normal. But apparently my secondhand discomfort was unfounded; not only was the whole thing over in seconds, but afterward Julie said: “Is it happening yet?” – because the O-Shot felt like nothing.

“How long will this last?” she asked Runels.

“Conservatively speaking, around nine months,” he answered. He added that, in Lacey’s case, results had persisted for nearly six years.

Julie beamed at me, and I smiled back, saying I was happy for her – but the truth was, I couldn’t get Dr Gunter’s and Dr Caulfield’s voices out of my head. Two smart and accomplished medical experts had insisted to me that satisfied O-Shot customers were dupes.

As a layperson, I couldn’t help but respect their authority. But as a human being, it was hard for me to discredit so many women’s stories. When they said the O-Shot worked, I believed them.

On my last day in Alabama, imaginary feuds between feminists and doctors and ethicists and patients ricocheted around my brain. I’d talked to so many people, read too many papers, and still had no clue what to think about the O-Shot.

So I asked Runels to inject my clitoris.

“This is insane,” a girlfriend texted me. “You don’t even have sexual dysfunction!”

I responded with some defiant emojis. It wasn’t orgasms I was struggling with – it was the conclusion to my article. So I stepped out of my jeans and held Pamela’s hand while Runels tugged on the headlamp. “Is it happening?” I said – but it was over. The procedure was brief and painless, and within hours I was boarding my flight home, eager to put the O-Shot to the test.

Unfortunately, results proved vague.

Every time I had sex I would ask myself: does this feel better than it did before my clitoris was injected with blood?

Even more mood-killing were the other questions pulsing through my mind: does having an orgasm as a result of this procedure make me a good or bad feminist? Have I taken a daring move by putting my clitoris first? Or have I sold out a century of progress by “obeying” Runels, a member of the patriarchy, who deluded me into thinking I needed him to fix me?”

These questions made sex worse. So I decided to depoliticize my body – to take psychology and medicine and feminism out of the equation, and forget I’d ever met him.

That did the trick. And it felt great.