What Is a JPEG? The Invisible Object You See Every Day

You're looking at dozens of JPEGs right now.

In 2012, the photograph of Barack and Michelle Obama embracing after his re-election was 'liked' over 4 million times. That photo, like the 250 million other images uploaded to Facebook every day is standardized; it is a JPEG-encoded image. When Obama's staff uploaded that image to Facebook, the company's software recognized it as JPEG-encoded data and created 4 different sized images using the JPEG compression standard built into its photo-management system. The image became visible to Obama's “friends” (and, apparently, to the NSA’s). It became ‘Like-able’ and ‘Share-able’ generating new data points in Facebook. If Obama's staff had tried to upload a different type of image — a RAW-encoded file or a Photoshop file, for example — Facebook’s software would not have recognized it. It would have refused to upload and the data and image would have remained invisible. The digital image, the political message would not have done its work.

We commonly think of JPEGs as a type of image. We talk of taking JPEGs, sending JPEGs, looking at JPEGs, posting JPEGs. But technically, JPEG is a compression standard, not an image type (the formal name for the latter is JFIF or EXIF). That compression routine is built into a digital camera’s software, taking the data stream from the camera's sensor and compressing or encoding it into a form that can then be read by software in Web browsers and operating systems, photo management and editing applications, and even surveillance systems.

JPEG was originally developed by the Joint Photographic Experts Group (hence its name). Despite many attempts by companies to claim ownership, it has effectively become an open standard, and therefore pervasive. Anyone looking to develop an imaging device or service uses JPEG. Social imaging applications like Instagram, lifelogging devices like Memoto and walled gardens like Facebook know that to use JPEG is to have a head-start: no need for plug-ins or learning curves. Like VHS and MP3, JPEG has lock-in as a standard. By adopting it, we can get on with the business of selling or using gadgets and services.

JPEG compresses image data... very efficiently. Let's take the example of Obama's photographer. When she pressed the software button, light hit the camera sensor, an array of silicon, solar or photovoltaic cells. Some of the light's energy was absorbed by the silicon, knocking electrons loose which were forced to flow in a particular direction creating a current: photons became electrons, light became electricity. In order for the software (including JPEG and Facebook) to be able to work with it, an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) in the camera converted this electricity to digital information a RAW data file.

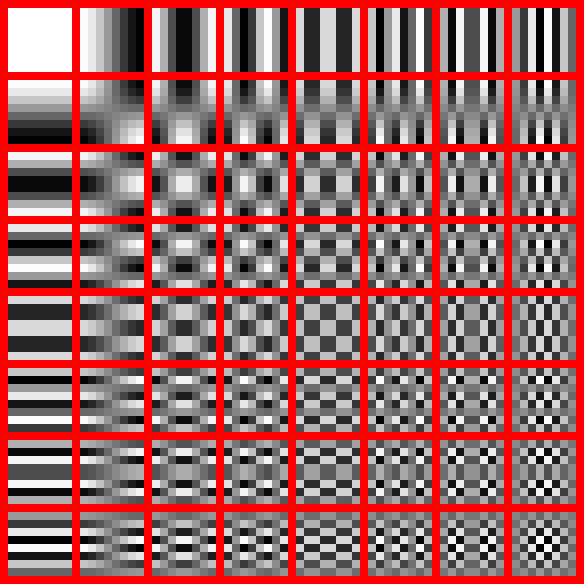

JPEG’s job was to get rid of as much data as it could while still making the image recognizable. It sampled the frequencies of different colors in the data captured by the sensor, attempting to determine how much they contributed to the visible image. Then it applied a series of algorithms (Discrete Cosine Transform, quantization, and Huffman coding) that discarded “extra” data. JPEG depends on the human eye's forgiveness. It fills in the gaps of the data it had removed (this is why JPEGs sometimes look blocky or smeared). The camera software compressed light-as-electricity-as-data into a visible file that the human eye could see as the First Family. That visibly powerful result, the encoded photograph, was written to the memory card ready to be uploaded and then decoded by the JPEG software built into photo management software, web browsers and surveillance systems.

Even Google, with its hegemonic power and massive reach, has not been able to dislodge the simple JPEG algorithm. In 2010 the company devised a more efficient compression algorithm and file format, WebP (pronounced “weppy”). Images encoded through WebP are visible in Google's own browser (Chrome), email system (Gmail), photo-management software (Picasa Web Albums) and search engine, but not in other leading browsers or photo management systems such as Firefox, Safari, Internet Explorer, Aperture or Lightroom. If you try and upload a photograph encoded with WebP to Facebook, the social network's software will scratch its virtual head, grey out the file name and fail to acknowledge the data. Literally, WebP does not compute.

As the world's most popular photo site, social imaging is a core part of Facebook's business. The company makes money from the Open Graph that draws the connections between users, their “friends,” and their content - connections that are mined and sold to advertisers. Images are a crucial part of that. Every time we upload an image of us hugging our wife and someone likes it, another data point is added to Facebook's map of relationships: Paul likes Obama. A new connection or data relationship is established. We can think of Facebook as a “relationship engine” generating new connections and content as images are uploaded, liked, shared and tagged. Images are particularly powerful connectors because they can be tagged with additional information, such as the date and location an image was taken and the people captured in the image. The tags establish connections which create even more data.

The importance of images in general and JPEG in particular can be seen in Facebook’s patents. Tagging digital media (US patent 7,945,653) cites “the association between the digital image and the email address [which] may be stored in the media database.” Managing information about relationships in a social network via a social timeline (US patent 7,725,492) states: “the social timeline further comprises photos of the members connected in relationship.” Facebook's lawyers as well as business people know that the image and the user are connected in Facebook’s database, ready for further association by subsequent use or for mining by advertisers and spooks.

The JPEG standard is particularly useful for driving a relationship engine like Facebook’s. Its efficiency and ubiquity mean more pictures are taken, uploaded and accessed, particularly in mobile space where size is important. Furthermore, during the process of JPEG-encoding, other data can be written into the image file: camera settings, time of imaging and even location. All of this metadata is useful for a system that thrives on possible connections (all the images taken on my birthday; all the photos from my holiday, etc.). This automatically generated metadata combines with the additional metadata we add manually when uploading, filing, and tagging a particular image, making our JPEGs even more powerful for Facebook its corporate customers and anyone else needing information from the relationship engine. But metadata for petabytes of images becomes unwieldy. In order to keep that relationship engine running smoothly, Facebook needs standards -- hence its dependence on JPEG.

Facebook's engineers have gone so far as to create a custom, JPEG-dependent system to manage that process. Called Haystack, the system is designed to physically manage the huge amount of data and metadata the relationship engine generates, and JPEG is right at its heart. Haystack makes searching, accessing and then using (tagging, liking, etc.) images as quick and easy as possible. It does so by storing hundreds of thousands of JPEG-encoded photos in fewer, much larger files. This saves space and makes individual photos easier to manage. To retrieve a particular photo, Haystack uses "needles" which represent a particular photo in an index. As Facebook engineers explain, this allows quick loading of the needle metadata into memory without having to dive into the larger Haystack store file.

Facebook uses JPEG not only because it's a free standard and ubiquitous, but because it is efficient. The quicker users can find and view images, the more images they will see and share and so the more data points the relationship engine has. The engine needs efficiency and JPEG is efficient. Facebook's patented relationship engine depends on it, and the system that manages our social archive, that the relationship engine mines and Haystack manages is built on it. This is why Facebook converts other kinds of images into JPEGs. If you've ever tried to upload a funny animated GIF or a web image saved in GIF format, you'll find that Facebook will turn it into a JPEG, removing the animations (a feature of GIF but not of JPEG).

JPEG is weird. You can't see it or touch it. Unless you're a programmer, you can't even find it in software outside of a Save dialog. But it is real. It does things; its traces and connections are everywhere: in JPEG image files, in social media archives and search engine and hard drive caches, in data-mining strategies and surveillance practices, in business models. But like Keyser Söze, the mysterious figure in Bryan Singer's film The Usual Suspects, JPEG just slips out of sight. But, like Keyser Söze, JPEG is real, even though we cannot touch it.

Realness has been on the rise lately. In politics, the revelation that the NSA has been hoovering up our data, and the sort of metadata that JPEG excels at creating, reminds us that that data is real, and has an existence in databases of Threats as well as databases of Friends quite apart from its relationship to us as a photograph or a Google Doc. In contemporary philosophy, a new cadre of “object-oriented ontologists” have been pushing this point more generally, urging us to widen the range of things we construe as objects. Even fictional or imaginary ones like Harry Potter still have effects in the world; objects so large we can’t grasp them like climate change are still real. And even weird ones like the JPEG standards, which disperse through our computers and networks like mist, rather than sitting on our desks like appliances. They are real because they all do things, have effects, connect with other objects.

When we are faced with complex, techno-social systems we seem happy to talk about them as things: usually big things “the Internet,” “Facebook,” “the NSA.” We even go so far as to connect those objects within other bigger objects like “the State” or “capitalism” or “globalization.” We are increasingly happy to talk about smaller things, Tweets, “selfies” even weird objects like JPEG. Like the patent lawyers who methodically outline the “modules” in Facebook’s tagging system and the engineers who map the caches and servers within Haystack, we line up objects — but almost always we privilege the human object. We (the photographer, the engineer, the user, the President) assume we are at the center of that system as its controller -- or its victim. We can look at Facebook as Zuckerberg’s relationship engine (or perhaps the NSA’s). We can say we are its master or its unpaid laborer.

Or, we can look at the relationship engine as having may parts, some human, some unhuman, some material, some immaterial. To say that JPEG is a powerful player in Facebook’s relationship engine is perhaps to turn a bit of computer code into a character - but it’s a character that helps us understand how images and social networks operate. The philosopher Jane Bennett has said that perhaps a bit of anthropomorphism is necessary if we are to get away from anthropocentrism or narcissism.

The photo of the Obamas circulated across social media. Its ideological message and the conversations and relationships it set in motion were an integral part of a political moment. Politics works through images and through social images. My photo at an Obama rally and its connections spins across Facebook and its connected databases because JPEG enable it too. To try to unpick those powerful realities by only talking about human objects is to miss something. When we are faced with a complex, powerful and potentially governmental system like Facebook, perhaps one way of starting to unpick how it works, what it does and what it means is to look at it from another object's point of view.

This post appears courtesy of Object Lessons.