The Mandela effect: Explaining the science behind false memories

Proof of time travel, interference from an alternate reality, a glitch in the matrix... or just bad memory? Two cognitive psychologists unravel the mystery of the ‘Mandela effect’

Have you ever been convinced that something is a particular way only to discover you’ve remembered it all wrong? If so, it sounds like you’ve experienced the phenomenon known as the “Mandela effect”.

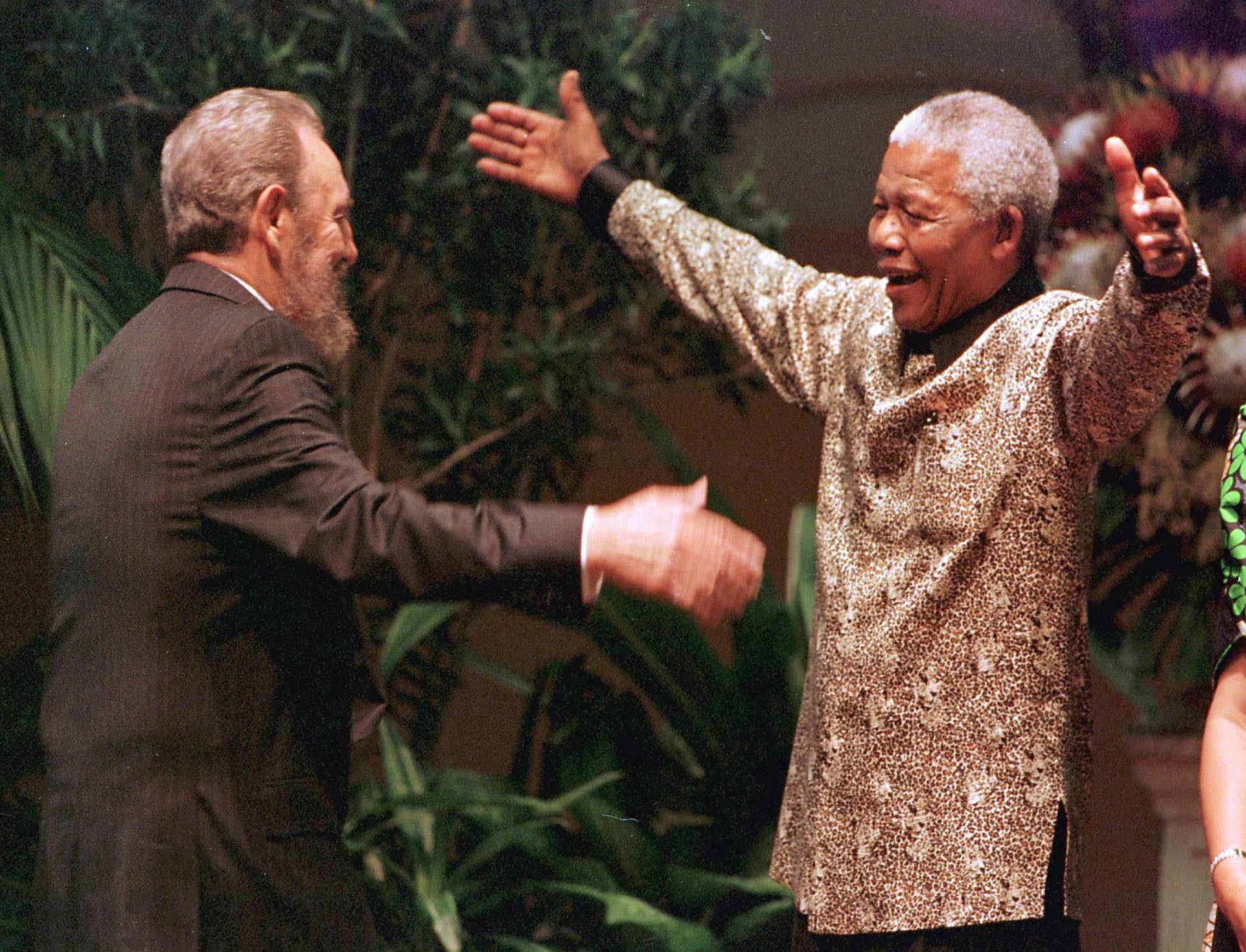

This form of collective misremembering of common events or details first emerged in 2010, when countless people on the internet falsely remembered that Nelson Mandela was dead. It was widely believed he had died in prison during the 1980s. In reality, Mandela was actually freed in 1990 and passed away in 2013 – despite some people’s claims they remember clips of his funeral on TV.

Paranormal consultant Fiona Broome coined the term “Mandela effect” to explain this collective misremembering, and then other examples started popping up all over the internet. For instance, it was wrongly recalled that C-3PO from Star Wars was gold, actually one of his legs is silver. Likewise, people often wrongly believe that the Queen in Snow White says, “Mirror, mirror on the wall”. The correct phrase is “magic mirror on the wall”.

Broome explains the Mandela effect via pseudoscientific theories. She claims that differences arise from movement between parallel realities (the multiverse). This is based on the theory that within each universe alternative versions of events and objects exist.

Broome also draws comparisons between existence and the holodeck of the USS Enterprise from Star Trek. The holodeck was a virtual reality system, which created recreational experiences. By her explanation, memory errors are software glitches. This is explained as being similar to the film The Matrix.

Other theories propose that the Mandela effect evidences changes in history caused by time travellers. Then there are the claims that distortions result from spiritual attacks linked to Satan, black magic or witchcraft. But although appealing to many, these theories are not scientifically testable.

Where’s the science?

Psychologists explain the Mandela effect via memory and social effects – particularly false memory. This involves mistakenly recalling events or experiences that have not occurred, or distortion of existing memories. The unconscious manufacture of fabricated or misinterpreted memories is called confabulation. In everyday life confabulation is relatively common.

False memories occur in a number of ways. For instance, the Deese-Roediger-McDermott paradigm demonstrates how learning a list of words that contain closely related items – such as “bed” and “pillow” – produces false recognition of related, but non-presented words – such as “sleep”.

Memory inaccuracy can also arise from what’s known as “source monitoring errors”. These are instances where people fail to distinguish between real and imagined events. US professor of psychology Jim Coan demonstrated how easily this can happen using the “lost in the mall” procedure.

This saw Coan give his family members short narratives describing childhood events. One, about his brother getting lost in a shopping mall, was invented. Not only did Coan’s brother believe the event occurred, he also added additional detail. When cognitive psychologist and expert on human memory Elizabeth Loftus applied the technique to larger samples, 25 per cent of participants failed to recognise the event was false.

Incorrect recall

When it comes to the Mandela effect, many examples are attributable to so-called “schema-driven errors”. Schemas are organised “packets” of knowledge that direct memory. In this way, schemas facilitate understanding of material, but can produce distortion.

Frederic Bartlett outlined this process in his 1932 book Remembering. Barlett read the Canadian Indian folk tale War of the Ghosts to participants. He found that listeners omitted unfamiliar details and transformed information to make it more understandable.

This process is called “effort after meaning” and occurs in real world situations too. For instance, research has previously shown how when participants’ recall the contents of a psychologist’s office they tend to remember the consistent items such as bookshelves, and omit the inconsistent items – like a picnic basket.

Schema theory explains why previous research shows that when the majority of participants are asked to draw a clock face from memory, they mistakenly draw IV rather than IIII. Clocks often use IIII because it is more attractive.

Other examples of the Mandela effect are the mistaken belief that Uncle Pennybags (Monopoly man) wears a monocle, and that the product title KitKat contains a hyphen (Kit-Kat). But this is simply explained by over-generalisation of spelling knowledge.

Back to reality

Frequently reported errors can then become part of collective reality. And the internet can reinforce this process by circulating false information. For example, simulations of the 1997 Princess Diana car crash are regularly mistaken for real footage.

In this way then, the majority of Mandela effects are attributable to memory errors and social misinformation. The fact that a lot of the inaccuracies are trivial, suggests they result from selective attention or faulty inference.

This is not to say that the Mandela effect is not explicable in terms of the multiverse. Indeed, the notion of parallel universes is consistent with the work of quantum physicists. But until the existence of alternative realities is established, psychological theories appear much more plausible.

Neil Dagnall is a reader in applied cognitive psychology and Ken Drinkwater is a senior lecturer and researcher in cognitive and parapsychology, both at Manchester Metropolitan University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies