Camille (1936 film)

| Camille | |

|---|---|

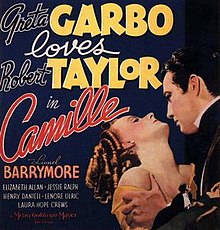

Theatrical Poster | |

| Directed by | George Cukor |

| Written by | James Hilton Zoë Akins Frances Marion |

| Based on | La Dame aux Camélias 1852 novel by Alexandre Dumas, fils |

| Produced by | Irving Thalberg Bernard H. Hyman |

| Starring | Greta Garbo Robert Taylor Lionel Barrymore |

| Cinematography | William H. Daniels Karl Freund |

| Edited by | Margaret Booth |

| Music by | Herbert Stothart Edward Ward |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Loew's Inc. |

Release date | December 12, 1936 |

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1,486,000[1][2] |

| Box office | $2,842,000[2] |

Camille is a 1936 American romantic drama film from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer directed by George Cukor, and produced by Irving Thalberg and Bernard H. Hyman, from a screenplay by James Hilton, Zoë Akins, and Frances Marion.[3] The picture is based on the 1848 novel and 1852 play La dame aux camélias by Alexandre Dumas, fils. The film stars Greta Garbo, Robert Taylor, Lionel Barrymore, Elizabeth Allan, Jessie Ralph, Henry Daniell, and Laura Hope Crews. It grossed $2,842,000.[1]

Camille was included in Time magazine's "All-Time 100 Movies" in 2005.[4] It was also included at #33 in AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions. Garbo received her third Best Actress nomination for Camille at the 10th Academy Awards in 1938.

Plot[edit]

Beautiful Marguerite Gautier is a well-known courtesan, living in the demi-monde of mid-19th century Paris. Marguerite's dressmaker and procuress, Prudence Duvernoy, arranges an assignation at the theatre with a fabulously wealthy prospective patron, the Baron de Varville. Marguerite briefly mistakes Armand Duval, a handsome young man of good family but no great fortune, for the baron. She finds Armand charming, but when the mistake is explained, she accepts the baron without hesitation.

Marguerite spends money carelessly, sometimes out of generosity, as when she bids a fortune on a team of horses in order to give an old coachman employment, but more often because she loves her lavish lifestyle and the late nights of dancing and drinking—and because she knows her days are numbered. She has consumption, which is a death sentence for anyone who lives as she does. She has bouts of severe illness, and during one spell, the only person who come to see her is Armand, bearing flowers (the baron contriving to be in England). She finds this out after she recovers, and she invites him to her birthday party (the baron having just departed for a long stay in Russia). During the party, Marguerite retreats into the bedroom with a coughing spell, and Armand follows. He professes his love for her, which is something she has never known. She gives him a key and tells him to send everyone home and come back later. While she is waiting for him, the baron returns unexpectedly. She orders Nanine, her maid, to shoot the bolt on the door. The baron, who is clearly suspicious, plays the piano furiously, not quite masking the bell. He asks who might be at the door and, laughing, she says, "The great romance of my life—That might have been."

At Armand's family home in the country, he asks his father for money to travel to prepare for his career in the Foreign Service. He sends Marguerite a scathing letter (he saw the baron's carriage), but when she comes to his rooms, they reconcile immediately. She sees a miniature of his mother and is amazed to learn that his parents have loved each other for 30 years. "You'll never love me 30 years," she says, sadly. "I'll love you all my life," he replies. He wants to take her to the country for the summer to get well. She tells him to forget her, but agrees in the end. However, she owes 40,000 francs. The baron gives her the money as a parting gift, and slaps her in the face when she kisses him in thanks.

Armand takes her to a house in the country, where Marguerite thrives on fresh milk and eggs and country walks and love. A shadow is cast by the discovery that the baron's château is in the neighborhood. Marguerite tells him she has asked Prudence to sell everything, pay everything. Armand asks her to marry him, but she declines.

Armand's father, though he acknowledges Marguerite's love is real, begs her to turn away from his son, knowing her past will ruin his chances. When Armand returns to the house, she is cold and dismissive and tells him the baron is expecting her. He watches her walk over the hill.

Back in Paris, at a gambling club, Armand comes face to face with the baron and Marguerite, who is ill. Armand wins a fortune from the baron at baccarat and begs Marguerite to come with him. She lies and says she loves the baron. Armand wounds the baron in a duel and must leave the country for six months. When he returns, Marguerite's illness has worsened. "Perhaps it's better if I live in your heart, where the world can't see me," she says. She dies in his arms.

Cast[edit]

- Greta Garbo as Marguerite Gautier

- Robert Taylor as Armand Duval

- Lionel Barrymore as Monsieur Duval

- Elizabeth Allan as Nichette, the Bride

- Jessie Ralph as Nanine, Marguerite's Maid

- Henry Daniell as Baron de Varville

- Lenore Ulric as Olympe

- Laura Hope Crews as Prudence Duvernoy

- Rex O'Malley as Gaston

- Mabel Colcord as Madame Barjon (uncredited)

- Mariska Aldrich as Friend of Marguerite (uncredited)

- Wilson Benge as Attendant (uncredited)

Production[edit]

According to a news item in Daily Variety, MGM had considered changing the setting of the famous Alexandre Dumas story to modern times.[5]

The time period was not changed, but Thalberg wanted the film to have a more contemporary feeling than earlier Camilles. He wanted audiences to forget that they were watching a "costume" picture. He also felt that morality had changed since the earlier Camilles, and the fact that Marguerite was a prostitute was not as shameful anymore; as a result, Garbo's character became more likable than in previous productions. The modernization of the story proved to be successful.[6]

While filming Marguerite's death scene, Robert Taylor brought his phonograph to Garbo's dressing room so that she could play Paul Robeson records to put her in the mood.

In the words of Camille's director George Cukor: "My mother had just died, and I had been there during her last conscious moments. I suppose I had a special awareness. I may have passed something on to Garbo without realizing it." Garbo later praised Cukor's sensitivity: "Cukor gave me direction as to how to hold my hands", said Garbo. "He had seen how, when his mother lay dying, she folded her hands and just fell asleep."

While producing Camille, producer Irving Thalberg died. After filming was ended, and post-production began, Louis B. Mayer assigned Bernard Hyman as the film's new producer. Hyman arranged re-takes, cut some scenes, or edited scenes from the original Thalberg production. It is not exactly known which scenes were edited or cut.

The famous death scene we see is not the original version from the first version of the film. In the original version, Camille died on the bed, had more words to say, and folded her hands before she died. This original death scene is lost. Cukor thought that it did not really feel very natural talking that much when you are about to die; so, Garbo's last scene was rewritten and reshot three times. In the first and second alternative endings, Camille was on the deathbed and said fewer words, but they still were not satisfied. They thought it seemed unreal for a dying woman to talk so much. In the third alternative ending, Camille was even quieter, and just slowly slipped away in Armand's arms.[7]

Previous film adaptations of the play premiered in 1912, 1915, 1917, 1921 with Nazimova and Rudolph Valentino, and most recently in 1926 with Norma Talmadge.

News items in Daily Variety and Hollywood Reporter on July 25, 1936, noted that John Barrymore originally was cast in the role of Baron de Varville, but a bout of pneumonia prevented him from working on the picture. Barrymore's brother Lionel was scheduled to replace John in the role; however, a few days later, it was reported that a change in casting resulted in Lionel Barrymore's assignment to the role of Monsieur Duval, and Henry Daniell's assignment to Baron de Varville. Cinematographer William Daniels mistakenly is listed as a cast member in early Hollywood Reporter production charts. Camille marked the screen debut of actress Joan Leslie, who appeared under her real name, Joan Brodel.[5]

Reception[edit]

Promotion[edit]

The "Selling Angles" section in BoxOffice Magazine, Dec. 26, 1936, suggested tips for selling Camille. Theatre managers were advised to make a display of some of the famous Camilles of past decades, including Garbo as the latest to join the list of immortal actresses; have local florists stage a "Camille Show"; find old reviews from metropolitan daily papers' back files and run them in conjunction with reviews of the modern film story; and print throwaways in the style of the old "Gas Light Era" programs. The suggested best "Catchlines" for selling Camille, according to BoxOffice, were:

- "Her love was like a great flame...burning...scorching...withering...and when the flame died, she no longer cared to live."

- "Her destiny was to be loved...but not to love...until she met the man who was to change that destiny."

- "Again...Dumas' classic love tale...with the screen's most dramatic love team – Garbo and Taylor."[8]

Premiere[edit]

Camille had its grand premiere on December 12, 1936, at the new Plaza Theatre in Palm Springs, California. Many celebrities attended the gala which cost $10 per seat. The desert resort of Palm Springs was turned upside down with all the commotion of the film's premiere. Some of the film was buried in stone to commemorate the celebration. Ralph Bellamy, who was a leading civic figure and Racquet Club owner in Palm Springs, was master of ceremonies. Rumors were spread that Greta Garbo was staying at the desert resort and would attend the premiere, but these rumors proved to be unfounded.[9]

At the gala premiere, Camille was given an enthusiastic reception; the critics praised it as the finest performance ever given by Greta Garbo, Robert Taylor, Lionel Barrymore, and Laura Hope Crews, and the best work by director George Cukor. The enthusiasm accorded the picture was seen as a tribute to the genius of the late Irving G. Thalberg, who conceived of, and was responsible for, the production. The 37-year-old Thalberg died just before the film's release.[10]

Box office[edit]

According to MGM records, the film earned $1,154,000 in the U.S. and Canada, and $1,688,000 in other markets, resulting in a profit of $388,000.[2]

Critical response[edit]

Camille has been well received by critics since its release, and the role of Marguerite is generally regarded as Greta Garbo's finest screen performance. Camille is often named as a highlight among 1936 films. Rotten Tomatoes reports 91% approval among 11 critics.[11]

On watching a scene in the film where Garbo is at a theater, Thalberg said: "George, she's awfully good. I don't think I've ever seen her so good." "But Irving", said Cukor, "she's just sitting in an Opera Box." "She's relaxed", said Thalberg. "She's open. She seems unguarded for once." Garbo's new attitude prompted Thalberg to have the script reworked. "She is a fascinating artist, but she is limited", Thalberg told the new writers. "She must never create situations. She must be thrust into them. The drama comes in how she rides them out."[6]

Awards[edit]

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10th Academy Awards | Best Actress | Greta Garbo | Nominated |

| 1937 New York Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Actress | Won |

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b "Box office / business for Camille (1969)". IMDb. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ a b c The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- ^ Camille at IMDb .

- ^ Time magazine.

- ^ a b "American Film Institute". American Film Institute.

- ^ a b Vieira, Mark (2009). Irving Thalberg: Boy Wonder to Producer Prince. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

- ^ "George Cukor About Camille". Garbo Forever.

- ^ "Exploitips". BoxOffice. December 26, 1936.

- ^ "Hollywood High Lights". Picture Play Magazine: 66. December 1936.

- ^ "Garbo Film Has Showing in The West". The World-Telegram. December 14, 1936.

- ^ "Camille (1936) on RT". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

External links[edit]

- Camille at Filmsite by Tim Dirks. Contains plot detail.

- Camille at the TCM Movie Database

- Camille at IMDb

- Camille at AllMovie

- Camille at the American Film Institute Catalog

- 1936 films

- 1936 romantic drama films

- American romantic drama films

- American black-and-white films

- Romantic period films

- American films based on plays

- Films based on Camille

- Films based on adaptations

- Films directed by George Cukor

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Films about prostitution in France

- Films produced by Irving Thalberg

- Films scored by Herbert Stothart

- Films with screenplays by Frances Marion

- 1930s English-language films

- Films scored by Edward Ward (composer)

- 1930s American films

- English-language romantic drama films