Architecture of Libya

Architecture in Libya spans thousands of years and includes ancient Roman sites, Islamic architecture, and modern architecture.

Roman[edit]

Tripoli was founded as a Phoenician colony in the 7th century BC[1] and Tripolitania became a Roman province after the destruction of Carthage in 146 BC.[2] Today, the ancient sites of Cyrene, Leptis Magna, and Sabratha are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[3][4][5] Other Roman remains include the Arch of Marcus Aurelius in Tripoli.[2]

Early Islamic era[edit]

There are few surviving monuments of early Islamic architecture in Libya. Some traces of the Umayyad-era fortifications of Tripoli have been discovered, consisting of thick stone walls.[6] The oldest significant examples of Islamic architecture are from the 10th century, when the region saw a period of relative prosperity under Fatimid control. During this time, the Fatimids developed forts and garrison towns to serve as staging posts between Egypt and Ifriqiya.[6][7]

The best-known site of this period is in Ajdabiya, where the Fatimids built a fortified palace and a mosque whose remains have been uncovered and documented by modern archeologists.[6][8] The mosque was built with mudbrick walls, though stone was used for pillars and as reinforcements for the building's corners. It had a hypostyle form typical of other Fatimid mosques, with rows of pillars forming aisles running perpendicular to the southwest wall (the qibla wall).[9] Like other early Fatimid mosques, it had no minaret when built, though one was added later.[9][8] The palace was a rectangular building made of stone, with rooms arranged around a central courtyard.[6] At one end of the courtyard, opposite the entrance, was a large reception hall consisting of an iwan terminating in an apse-like section projecting from the rest of the building. This apse was covered by a semi-dome with squinches.[10]

Another important Fatimid site is Madina Sultan (present-day Sirte), which has also been excavated by modern archeologists. It was a town enclosed by an oval perimeter wall with several gates.[6] Among the most significant buildings discovered is the main mosque, which was also hypostyle in form, though its aisles ran parallel to the qibla wall instead of perpendicular to it. It had a monumental entrance portal on its north side, a feature shared with the Fatimid Great Mosque of Mahdiya. Some traces of the mosque's original decoration have been discovered as well, including coloured glass windows with carved stucco frames.[11]

In Tripoli, the oldest Islamic monument is al-Naqah Mosque,[6] though its history is not well-known.[7] It may have been built by the Fatimid caliph al-Mu'izz in 973, though it may be older.[6] An inscription records that it was reconstructed in 1610–1611 (1019 AH)[7] by the governor Safar Dey.[12]: 390 Its overall shape is irregular, suggesting multiple modifications throughout its history, and it incorporates re-used Roman and Byzantine columns. It has a hypostyle form with columns supporting rows of domes.[6][7]

Other Fatimid sites are attested in historical sources but not all have been investigated by archeologists.[13] Few major monuments have been preserved from the period between Fatimid rule and later Ottoman rule, although a number of small local mosques across the country may still date from the pre-Ottoman period. For example, there is a 12th-century mosque in the Awjila oasis with a hypostyle prayer hall covered by conical domes. The region of the Nafusa Mountains region contains some mosques dating to the 13th century or earlier, characterized by their low profile, partially-underground structures, and lack of minarets.[13]

Ottoman period[edit]

The Ottomans conquered Tripoli in 1551 and made it the capital of a province roughly corresponding to modern-day Libya. The first Ottoman governor, known as Dragut or Darghut (d. 1565), repaired and redeveloped the city's fortifications, giving the old city (medina) the roughly pentagonal shape it has today.[12]: 389 He also built a new palatial complex, the Saray Dragut, and a new congregational mosque nearby, the Sidi Darghut Mosque, which became a new focus of urban development in the city.[7][12]: 389–390 The mosque was partly destroyed in World War II and subsequently rebuilt.[7]

Tripoli's apogee came under the rule of the Qaramanli dynasty between 1711 and 1835. Ahmad Bey, the dynasty's founder, added significantly to its urban fabric.[7][12]: 394 He commissioned the Mosque of Ahmad Pasha al-Qaramanli, one of the largest and most important mosques in the city, built between 1736 and 1738. It is a large hypostyle mosque covered by 25 domes supported by marble columns, with an attached madrasa and a mausoleum for Ahmad Bey. On the inside, the mosque is heavily decorated with underglaze-painted tiles and carved stucco.[7] The mosque's minaret has the pointed form typical of Ottoman minarets,[7] which is also typical of other Ottoman-era mosques in the city.[12]: 393 The mosque and its surroundings express a provincial Ottoman style with some similarities to contemporary architecture in Ottoman Tunisia.[7]

Italian period[edit]

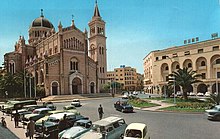

During the period of Italian colonial rule, further buildings were constructed, including the Tripoli Cathedral and the Benghazi Cathedral.[14] Up to the 1920s, Italian architects in Libya designed buildings that referenced either Classical architecture or Islamic ("arabized") architecture. Local colonial architecture later became influenced by Italian Rationalism.[15]

Modern[edit]

Skyscrapers such as Tripoli Tower, Corinthia Hotel Tripoli, and JW Marriott Tripoli were built in the 21st century.

References[edit]

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Tripoli (ii)". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Libya". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ "Archaeological Site of Cyrene". UNESCO.

- ^ "Archaeological Site of Sabratha". UNESCO.

- ^ "Archaeological Site of Leptis Magna". UNESCO.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Petersen, Andrew (1996). "Libiya (Libyan Arab People's Socialist State)". Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. pp. 165–166. ISBN 9781134613663.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. pp. 218–219. ISBN 9780300218701.

- ^ a b Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. p. 66. ISBN 9780300218701.

- ^ a b Petersen, Andrew (1996). "Libiya (Libyan Arab People's Socialist State)". Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. pp. 86–87, 165–166. ISBN 9781134613663.

- ^ Arnold, Felix (2017). Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean: A History. Oxford University Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN 9780190624552.

- ^ Petersen, Andrew (1996). "Libiya (Libyan Arab People's Socialist State)". Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. pp. 165–166. ISBN 9781134613663.

- ^ a b c d e Micara, Ludovico (2008). "The Ottoman Tripoli: A Mediterranean Medina". In Jayyusi, Salma Khadra; Holod, Renata; Petruccioli, Attilio; Raymond, André (eds.). The City in the Islamic World. Vol. 1. Brill. pp. 383–406. ISBN 978-90-474-4265-3.

- ^ a b Petersen, Andrew (1996). "Libiya (Libyan Arab People's Socialist State)". Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. pp. 165–166. ISBN 9781134613663.

- ^ McLaren, Brian (2006). Architecture and Tourism in Italian Colonial Libya: An Ambivalent Modernism. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98542-8.

- ^ McLaren, Brian L. (2002). "The Italian Colonial Appropriation of Indigenous North African Architecture in the 1930s". Muqarnas. 19: 172–173.