There's a silver jubilee party in Seattle next week, and an unlikely one at that. Sub Pop – the grunge label! The Nirvana label! The label with all the lumberjack guys! – celebrates its 25th anniversary with a free festival in its hometown on 13 July. Of course, in true Sub Pop fashion – this being a label that has long revelled in false mythologies and downright lies – it's not actually the 25th anniversary: Sub Pop was actually founded by Bruce Pavitt in 1986, and had existed as a radio show, a fanzine, magazine column and a cassette label before then. Instead the festival marks the 25th anniversary of Pavitt and his co-conspirator Jonathan Poneman getting their first office in 1988. Except even then the dates are all wrong: they moved into that first office on 1 April, not 13 July. But what the hell.

It's a minor miracle that Sub Pop is here at all. When the label turned 10 (or 12) in 1998, few – including its founders – would have bet on it reaching the new century, let alone still being one of the cornerstones of American alternative music in 2013. It was haemorrhaging money on new offices away from its base and on ill-advised deals for new bands; its A&R strategy – signing soft pop acts such as the Pernice Brothers – seemed baffling to those who viewed it as a rock'n'roll label; the company appeared to have compromised its independence by allowing Warner Music Group to take a 49% stake in it; Pavitt had stopped taking an active role and wanted the label to close.

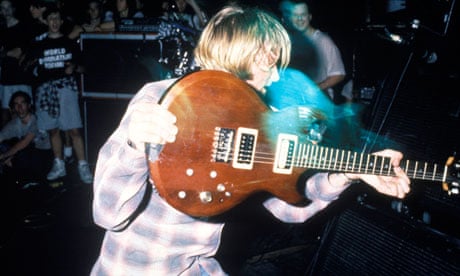

It looked, from the outside, like a case of indie Icarus syndrome: having once been the most feted label in the world after unearthing Nirvana , Soundgarden and the grunge supporting cast, it had overreached itself and was sure to fall. And from the inside it looked even worse: in 1997, a group of Sub Pop employees launched an unsuccessful coup against Poneman, so discontented were they were with his helming of the label.

"It was a dark time at the company," says Megan Jasper, Sub Pop's vice president, who has been associated with the label one way or another almost since its inception. "There were people who didn't know if they would have their jobs in six months." Mark Arm of Mudhoney – the band so totemic of Sub Pop that they're almost the fluffy dice in its car windscreen – delivers an anecdote that illustrates the state of the company in the mid-90s. "I work at Sub Pop and there's a poster for the 15th anniversary in 2003. This is at a time when they had the Shins and Iron and Wine and the Postal Service, so they were back on the upswing. The poster reads: 'Sub Pop's 15th anniversary – celebrating 10 years of great music!' 'Cos there were some … not-so-great years."

"There weren't many people going out and buying the records," Poneman says. "But we were making significant amounts of money from odd projects and from the early formulation of a film and TV licensing department which was very proactive. Now every label, every publishing company and every management company has someone doing that. At the time independent labels did not have someone doing that but we did. So, the music of Combustible Edison and the music of Pigeonhed generated lots and lots and lots of money and helped sustain the label through some lean times. But don't get me wrong – I put millions and millions of dollars into keeping the label afloat, because I did have the belief that there was going to come a time where we would be able to come out with our credibility intact."

Poneman got the money to put into the label from the sale of nearly half of the company to Warner, but that created pressures and expectations Sub Pop had never had to deal with before.

"Our corporate partners had the expectation we were going to be able to sign another Nirvana," Poneman says. "We had a good track record. And so the circumstances came down to Warner having one set of expectations, Bruce having another set, and I having a third set. And that kind of led to a mess. We found ourselves going from being the little rascals playing in the music industry to suddenly competing for bands in our own social group who were being lured by Sony Music or BMG, even our own business partners at Warner. And then there were all these startup labels waving cheques with hundreds of thousands of dollars."

"They were trying to compete in bidding wars," remembers Mudhoney's Steve Turner. "There was an English band called the Yo Yos, and to me that was: 'Really? They won a bidding war for the Yo-Yos who put out one shitty record and broke up?'"

Mark Arm recalls internet startups in the Pacific north-west paying ludicrous salaries to employees, and Sub Pop feeling it had to do the same, with one executive reputed to have been paid a preposterous – by Sub Pop's standards – $100,000 a year. "That is not a very smart way to deal with the few million you have," Arm says. "You're just going to burn through it. It's not like you have hundreds of millions, you have a couple of millions."

Those were the circumstances in which a group of employees, horrified at the direction Sub Pop was taken, tried to take matters into their own hands in 1997 with their move against Poneman, who was also dealing with the death of his father at the time.

"What they felt was that the company was bloated, the company was mismanaged, the company was growing too quickly, they feared for its future. They came together with Bruce and decided to go to one of the higher-ups within the Warner Music Group and share these concerns," Jasper says.

"It was so heartbreaking, because on the one hand, the concerns the people had were correct. They were right. And they cared so fucking much about the company and its future that they went to this extreme. The problem was that they should have gone to Jonathan."

The story of how Sub Pop resurrected itself is one of independent music's most heartening tales, yet it often gets overshadowed by the doomed romance of the grunge years. Crucial to it were the Shins, a young band from New Mexico who had nothing in common with the music that made Sub Pop famous. "My knowledge of the Shins went back to the late 90s, when James [Mercer] had the band Flake," Poneman says. "Isaac Brock [of Modest Mouse] had gone down to Albuquerque, and he went on and on and on about this band he had seen called Flake. So a couple of years later, when Zeke Howard of Love As Laughter went through Albuquerque and came back saying he had a CD from this really good band, I knew who he was talking about."

Mercer was hardly foaming with excitement when Sub Pop's interest became apparent. "I do remember wondering: 'Is Sub Pop cool?'" he says. "Because the stuff that I was listening to, that I was really interested in, was that new wave of classic pop-sounding stuff, like the Apples in Stereo. And they were all on these really kooky indie labels. That's who I aspired to be like, and I wanted to be doing what they were doing."

Nevertheless, a deal was done, though initially only for one single. "That had more to do with my being gunshy because I had championed so many records that I thought were great, but were wholly misunderstood by the grunge-loving, late-90s Sub Pop audience," Poneman says.

"Then," Mercer says, "during a month or so of listening to songs, they said: 'We should do a record.' They signed us for three records."

Oh, Inverted World – the first album by the Shins – was released in June 2001, and proved to be a landmark for the label, and not just because it became a huge seller. "They brought something that really changed the label," Megan Jasper says. "We listened to their music and everyone – everyone – loved it. There was a confidence and a pride that came from working with a band that no one knew about but you knew was fucking great. All of a sudden people started caring in a way they didn't before."

Nevertheless, commercial expectations were low at first. "I remember Jonathan at one point saying he thought maybe we could sell 20,000 records," Mercer says. "And I was just: Oh my God – that would be crazy.' It was a big deal." But, buoyed by great reviews, the record took off. And then kept taking off some more. Mercer allowed the song New Slang to be used in a McDonald's advert – Sub Pop had been ahead of the curve in setting up a licensing department to place songs in other media – and then something even more important happened. That something was the film Garden State.

When Zach Braff started work on his directorial debut, he was a little known TV actor. By the time it was released in 2004, the show he appeared in – the hospital sitcom Scrubs – was a hit, and Garden State was an indie event movie. For one key scene in the film he had Natalie Portman's character pass his own character a set of headphones to hear New Slang, telling him: "You gotta hear this one song – it'll change your life; I swear." It was arguably the biggest boost a Sub Pop act ever had, far exceeding Mercer's hope that "maybe we'll get a free video out of it".

"That was a perfect reflection of exactly what was happening with that band," Jasper says. "It was just miraculous," Poneman reckons. "It had every bit the impact on the label this century that Nirvana did in the last. It empowered all of the bands from a commercial perspective."

The Shins' success empowered Sub Pop, too, making it a destination label once again. "A lot of artists wanted to be on the same label as the Shins," Jasper says. "They wanted to have a better shot at touring with them, they wanted to be associated with them."

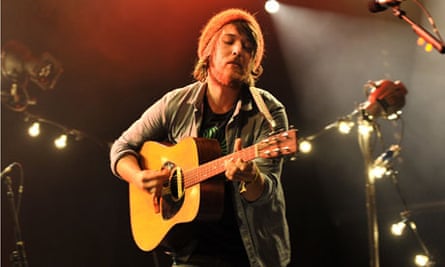

Oh, Inverted World confirmed a new identity for Sub Pop. With acts such as Iron and Wine and the Postal Service (whose only album became another huge seller for the label, after arriving almost by chance because of Sub Pop A&R head Tony Kiewell's friendships with Ben Gibbard and Jimmy Tamborello), followed by the likes of Band of Horses and Fleet Foxes, it became the home of a new strain of dreamy American indie music – the exact opposite of the grunge bands. And it won new audiences.

"You went to any of those shows – Shins, Fleet Foxes, Postal Service, Iron and Wine, even Band of Horses – and you didn't just see 20-year-olds," Jasper says. "You saw 20-year-olds, 30-year-olds, 40-year-olds, 50-year-olds. And that's what was weird. But Sub Pop had become a place that was able to attract artists that could speak to many different types of people."

"We were putting out music that everybody hopes for – music that's connecting with people," Poneman says. "You are able to sell the music, you are able to inspire people. It was a good streak. Whether or not we're still on it remains to be seen. That's not to suggest we're in a downtime now – but we were particularly hot in the first decade of the new century."

Poneman was recently diagnosed with Parkinson's. He has no plans to retire from the label – "All I can do is keep on keeping on as long as it feels like it's something I want to do." And how long might that be? "As long as there's that song out there, I feel like it's something I can do for a very long time."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion