Ry Cooder has ‘Los Angeles Stories’ to tell

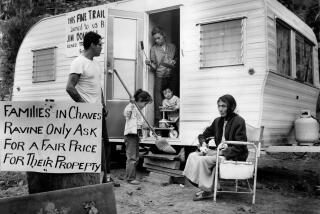

Let’s start with the hands, Ry Cooder’s hands. They’re large, expressive: hands you could see wrapped around a guitar neck, or in the act of making things. They move when he speaks, creating shapes in the air that take form and dissipate, all in the space of a few words. On a Friday afternoon at the Petersen Automotive Museum, Cooder is using those hands to help recount the saga of “El Chavez Ravine,” a 1953 Chevy pickup he commissioned to be rebuilt in 2007 in the style of a vintage ice cream truck and covered with an elaborate mural, by the artist Vincent Valdez, depicting the eviction of Mexican American families from the neighborhood that is now home to Dodger Stadium.

The same story inspired Cooder’s 2005 album “Chavez Ravine,” the first installment in his so-called “California Trilogy” (the others are “My Name Is Buddy” [2007] and “I, Flathead” [2008]), and, in some ways, it also sits as a ghost narrative to his first book, “Los Angeles Stories” (City Lights: 230 pp., $15.95 paper), a collection of eight loosely linked pieces of fiction that go back in time to a different Southern California, where musicians and aircraft workers and trolley drivers come together and apart in little bungalows and bars. (His latest album, released in August, is “Pull Up Some Dust and Sit Down.”)

“We lived a block from Douglas Aircraft in a crappy duplex,” remembers Cooder, who grew up in Santa Monica during the 1950s. “The hillbillies would be drinking beer up on Ocean Park Boulevard. My father said, ‘Don’t ever go up there.’ So I went up there and listened to the jukeboxes in the bars. It was in the air somehow, it seemed to be real.”

What Cooder’s getting at, that elusive “ it,” is the authenticity of old Los Angeles, a “nothing place,” and yet one with its own history and style. This is what he has built his work around these last several years, and what he continues to want to explore, the handmade world of people who “aren’t fancy talkers and thinkers. They don’t ride any wave. They’re just there. But if you go to any of those little houses, they’ll tell you some stories. People will tell you the most amazing things.”

“Los Angeles Stories” operates almost entirely on such a principle, offering a deftly rendered panorama of the city between 1940 and 1958. Its characters are the forgotten, the lost: a man who goes door-to-door for the Los Angeles City Directory, a tailor who make suits for musicians, a drummer on a three-week gig in Kingman, Ariz., sneaking back into California with piano player Billy Tipton and her underage girlfriend under the cover of night.

“These stories,” Cooder says, “became my favorite thing to do. I thought: I can just sit here. I can say whatever I want, and these people will do whatever I tell them.” Even more, he continues, in the act of writing, he “remembered things that people have told me, so a lot of what’s in the book is from reality.”

As a case in point, he cites “End of the Line,” set in 1954, in which a motorman, laid off after 15 years on the job, takes his Red Car out for one last run. “It’s about a twenty-mile run from downtown to the beach on Jefferson Boulevard,” Cooder writes. “First you pass through the downtown residential area. West of Crenshaw, Jefferson is no-man’s land until you get to the Hughes Aircraft sheds off to the left. Then you start to smell the ocean and the Ballona Creek marsh. Downtown L.A. smells pretty bad, unless it’s raining.” The motorman’s ex-wife works at Grayson’s department store, where she discovers the store manager embezzling funds.

“That’s a true story,” Cooder acknowledges, with a quiet laugh. “My dad was the one who caught the manager of the store. He told me that story. And so, I’m writing this thing about the motorman, and I thought: Wait a minute, I know. The first wife worked for Grayson’s. I know that whole story, don’t I? I think I do. I started to write and it all came flooding back.”

For Cooder, what’s at stake is memory, although it’s memory in a collective, as opposed to an individual, sense. Among his influences was the City Directory, a compendium of businesses published annually, in the days before the telephone book. “A friend brought me a copy,” he recalls, “a huge, enormous thing, heavy, heavy. Tiny thin paper, tiny type. And I got to reading this thing, page by page. It’s so fascinating: the names, the jobs. Pants presser, pants presser, pants presser. More pants pressers than any other work. I learned a lot from that book. It helped me get the names right. Real names mean something. They tell you a lot.”

Then, there is the “California Trilogy,” with its vivid evocations of time and landscape, and especially “I, Flathead,” which came packaged with a novella, written by Cooder, that gave a back story to the songs. “After ‘Flathead,’” he explains, “I said, ‘This is so much fun I’m going to keep doing it.’” When the idea of a tour with old friend Nick Lowe arose, he seized the opportunity. “I thought: You ought to have something to sell,” he says in a laconic drawl. “I didn’t want to get into the T-shirt business, so I wrote this book instead.”

Originally self-published — “I had some printed in China, but they did everything wrong” — it ended up in the hands of City Lights Books editorial director Elaine Katzenberger, who streamlined the stories, stripping out unwieldy language. Cooder remembers: “I said, ‘Oh, I see how you’re moving things around more efficiently. I didn’t know that stuff but I can learn.’ So I went back in and hacked away. It’s like anything, you have to get used to it. Songs I know how to do. But the more you do it, the better you get.”

This is the same aesthetic Cooder brings to his music — or to “El Chavez Ravine,” for that matter — the sense that what’s important is the crafting, that it all needs to be well made. “With a song,” he observes, “you can get an atmosphere going, that’s what a song is, it’s a place to be. I tried to do something similar with the stories, to take people places they hadn’t been before, places that were familiar and mysterious.”

Equally important is a song’s ability to forge connections, which is what he hopes for “Los Angeles Stories,” as well. “You know,” Cooder says, gesturing at the ice cream truck, “people come and look at this, and they don’t know the story at all.” He talks about the Arechiga family, “the last family to hold out,” their name part of the history of the city, if anyone remembers.

“Where we are right now,” he says, his hands articulating hidden shadows, “so much has been forgotten and put away. But I still think we want to see things that we don’t know about. Go around a corner, and you might have an experience. You might see something you didn’t know was there.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.