NASA is best known for solving the mysteries of space, millions of miles from our home planet. It’s now joined the investigation into some very strange and very old earthbound formations in northern Kazakhstan, the New York Times reported (paywall).

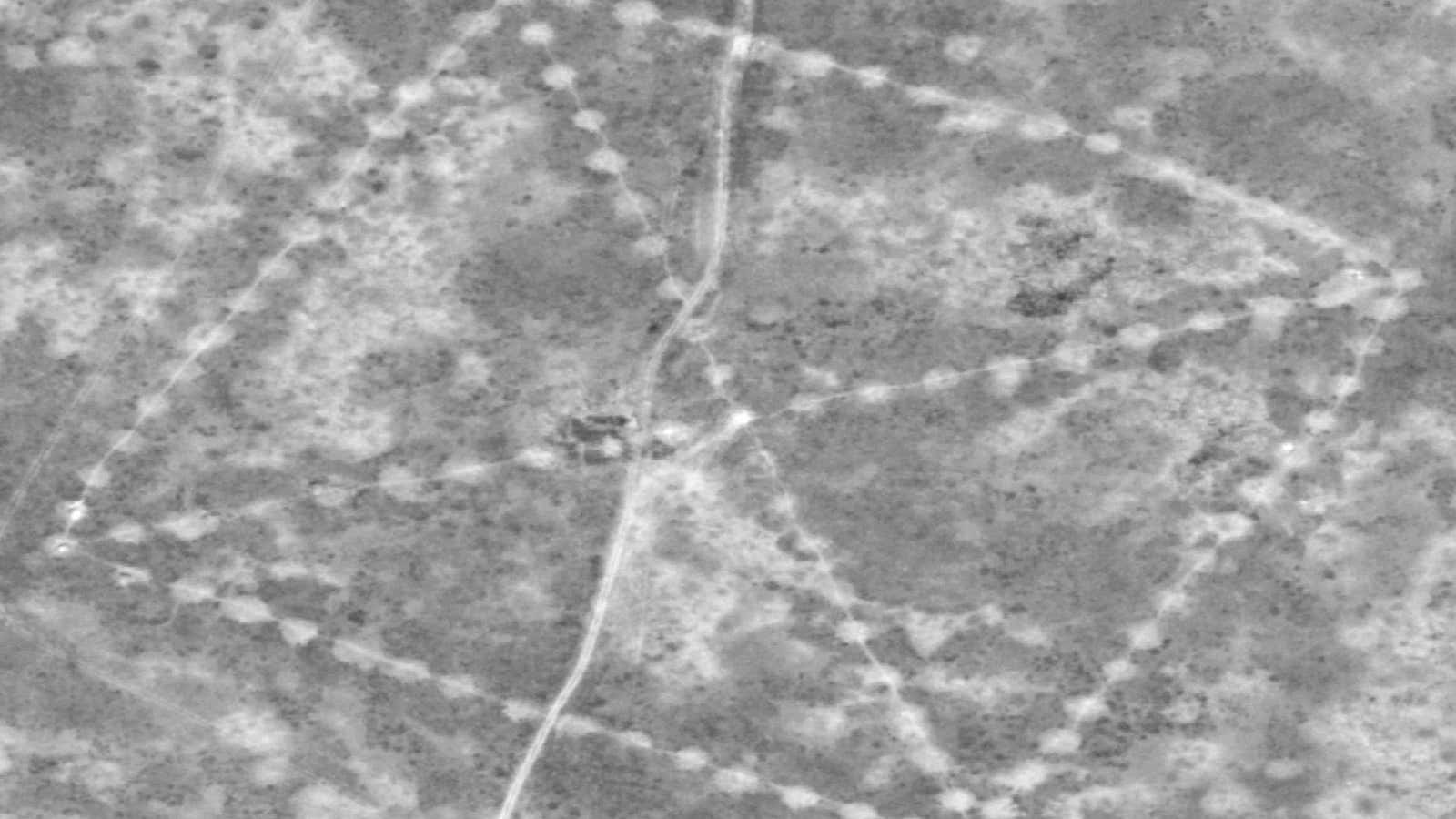

These huge formations—called the Steppe Geoglyphs—were first discovered on Google Earth by Dmitriy Dey, an amateur archaeologist, in 2007. Since then, Dey has found about 260 of the land designs—which resemble crop circles, but are much stranger.

Archaeologists don’t know what they are or who built them, but they estimate that the oldest is 8,000 years old.

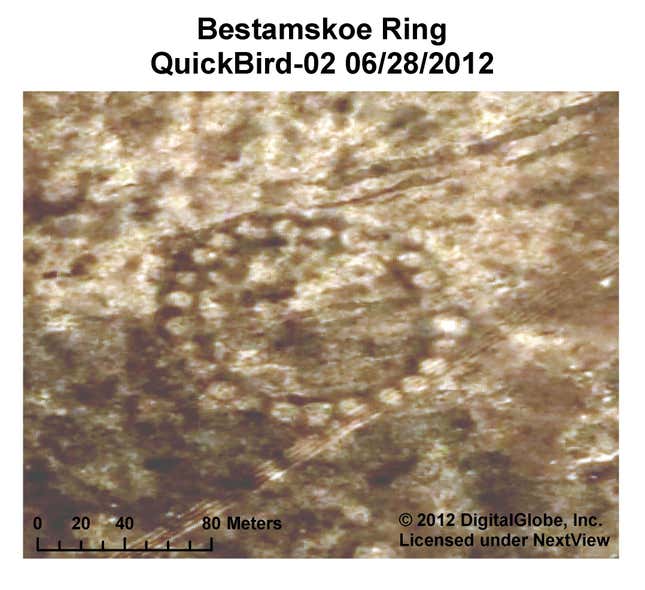

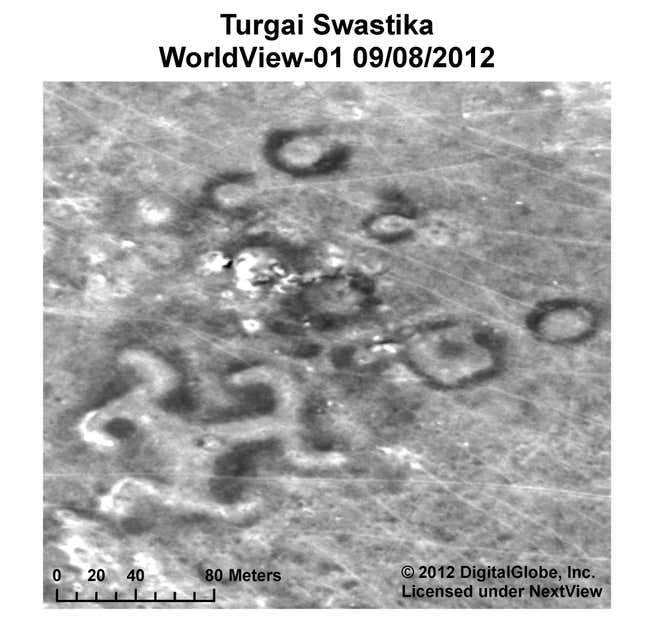

Dey’s research was apparently convincing enough to persuade NASA to help figure out what these things are. NASA’s satellite images (taken by contracter DigitalGlobe) of the formations are the first time they’ve been photographed from space.

NASA has also directed the astronauts on the International Space Station to start photographing the region, so perhaps look out for new photos on Scott Kelly’s Instagram in the coming weeks.

The geoglyphs—formed by man-made mounds, divots, trenches, and banks—come in a variety of shapes.

One of them, called the Bestamskoe Ring, is a circle made up of dozens of smaller circles. Another, named Ushtogaysky Square, is 810,000 square feet—each 900-foot side is as long as an aircraft carrier—with an X-shape through the middle. The weirdest of all, though, is the Turgai Swastika, which, you guessed it, resembles a swastika. (The swastika was a popular symbol long, long before the Nazis appropriated it.)

Thousands of years ago, the northern region of Kazakhstan offered rich hunting grounds for nomadic Stone Age tribes. (Ushtogaysky Square, the largest of the formations, sits close to a known Neolithic settlement.) The problem is, the formations would have taken far longer to build than how long historians currently believe these tribes stayed in one place.

“The idea that foragers could amass the numbers of people necessary to undertake large-scale projects—like creating the Kazakhstan geoglyphs—has caused archaeologists to deeply rethink the nature and timing of sophisticated large-scale human organization as one that predates settled and civilized societies,” Persis B. Clarkson, an archaeologist at the University of Winnipeg, told the Times.

Dey dismisses theories that aliens are behind them—he believes the elevated straight lines on the geoglyphs were “horizontal observatories to track the movements of the rising sun.”

That would make them a close cousin to structures like Stonehenge, and the recently discovered “Superhenge,” which scientists also theorize may have been sun-related.