a work of explication in five acts

I. It’s After The End Of The World, Don’t You Know That Yet?

To say Sun Ra once said “It’s after the end of the world, don’t you know that yet?” would be a misrepresentative understatement. He had June Tyson repeat it, nine times within the first forty-five seconds of the first song on the soundtrack to the film Space Is The Place. He did not intend it as a clever bon mot, but as a point of emphasis. We would do well to accept the point, and if you’re a long-time reader of superhero comics, it should be easy enough to do so, as you’re already familiar with the tendency of life to go on unabated after much-hyped apocalyptic events. If you’re an Alan Moore reader, you might be aware that the conclusion of his Swamp Thing arc, "American Gothic," coincided with the company-wide Crisis On Infinite Earths, though his run continued another year with no decline in quality. You might recall how that event’s reset-button-pushing led Moore to write a final Superman story, before John Byrne began another one the following month.

Decades later, Moore had his own line of superhero comics, one of which, Promethea, was meant to serve as a primer for Moore’s sincere belief in the occult. The end of the world was prophesied, tied to 2012, and when the world ended at the end of its run, it was a positive experience for everyone alive, a pulling away of the veils that divide humanity, with the world becoming enlightened and moving to a better place. This concluded Moore’s work with his America’s Best Comics imprint, with an epilogue appearing in an issue of the series Tom Strong that ran alongside it. This is an optimistic ending. His works for Avatar Press about the stories of H.P. Lovecraft, end with the Earth and humankind descending into a darkness from which it will never emerge.

Whether Moore truly believed the world was going to end in 2012 is impolite to press at this late date. The world did not end, the globe kept spinning, although whether an antichrist took to the world stage remains debatable as ever. Certainly the charge of such an existential threat gave some urgency to the creation of still another apocalypse, this one in The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century, which began in 2009 and ran for three yearly issues, taking place in 1910, 1969, and 2009, building up tension for an apocalyptic conclusion. The ending was anti-climactic; the series continues anew in the latest volume, The Tempest, a few years later. While changes in cultural context have only reinforced the feeling that Century’s conclusion, with its depiction of Harry Potter as anti-christ, read like a petty grievance being blown out of proportion, such dialogue between British genre literature was understood as the series’ raison d’etre, and so forgivable as we move on to Moore addressing an even more dire cultural landscape.

II. Legion Of Substitute Heroes

The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen, beginning in 1999, continued the stories of characters created in 19th-century British novels, and integrated disparate works into a shared universe much like that found in Marvel or DC comics in the sixties. This high-concept idea stemmed essentially from its authors understanding that such works, frequently serialized, with antecedents to twentieth-century pulp and the general cultural ferment from which the individual superhero narrative emerged in the 1930s. From there it posits a “shared universe” that folds in as much as it can from already existing texts.

Originally premised on the use of figures from 19th century literature now in the public domain, moving towards the present has necessitated misspellings of popular figures, and filling out background detail with figures whose creators are unlikely to sue. Historical reality still needs to be covered, and when fiction has done so, it stands in: Chronicles of World War II used Chaplin’s character from The Great Dictator, Adenoid Hynckel, as a stand-in for Adolf Hitler. Discussing the present day in The Tempest, Johnny Gentle from David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest is used as a stand-in for Donald Trump. This is more of a background gag than a major plot point, but if you’re discussing the present moment, Trump’s existence needs to be acknowledged. Still, the project is defined by talking about fiction, the culture that dictates our discourse, which in 2019 means talking about superheroes explicitly, as their exploits are everywhere in movie theaters and television programs, understood and appreciated by such a broad cross-section of the public that it surely includes people who would’ve looked down on comic books as sub-literate garbage for the first twenty years of Moore’s career.

The superhero stuff is freighted with meaning for Moore, due to the deathless influence of his work in the genre on what came after. His work using characters he created as analogs for old Charlton properties has influenced decades of work, and now the DVD shelves at big-box stores are as dominated by superhero movies as the shelves of a comic store in 1992 were with superhero comics. The characters are barely characters from a literary perspective, and the omnipresence of the genre is greater than any individual character could be, and so there is no need for analogs.

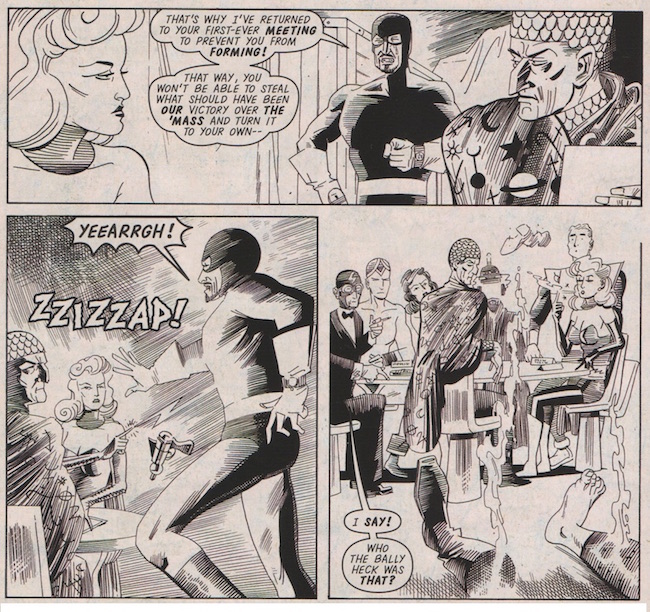

The superheroes appearing in this volume of League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen are sourced from the public domain, having previously appeared decades ago in British comics that attempted to cash in on American comics by ripping them off, before either being sued or just collapsing as half-hearted scams so often do. Each issue contains a back-up strip where these characters are a team, establishing them in a parodic early-sixties context, as a supplement to their appearance in the main narrative. These are then followed by back covers with fake letter pages, similar to those found in Moore’s series 1963, begun for Image Comics in 1993 and never concluded.

While I said these characters are not directly analogous to popular superheroes, there is actually a pretty straightforward parody of the Batman origin contained in issue 5. In keeping with my opening Sun Ra reference, it can be said that Moore “unmasks the Batman” here, taking the critique of the character that he is a rich person who beats up poor people and porting it over to the more delineated British class system, where it feels even more ridiculously unnecessary.

Meanwhile, each issue of The Tempest is designed to have its front cover resemble the sort of comic that has appeared on store shelves and had popularity without superheroes: girls’ comics, humor comics, horror comics, Classics Illustrated. The issues themselves then sort of half-heartedly embrace this: A segment of the “girl’s comics” issue includes a comic made using photographs, the horror issue has interjections of a ghoulish host, the humor issue plays up the farcical elements a bit more. Meanwhile, the inside front cover has supplemental text providing a biography of a British cartoonist that the industry mistreated.

III. Hell Is Empty And All The Devils Are Here

This might seem a confusing array of conceptual baggage, and it is. The book is dense, and reading each issue as it came out, it was difficult to find a throughline by which to ascertain meaning.

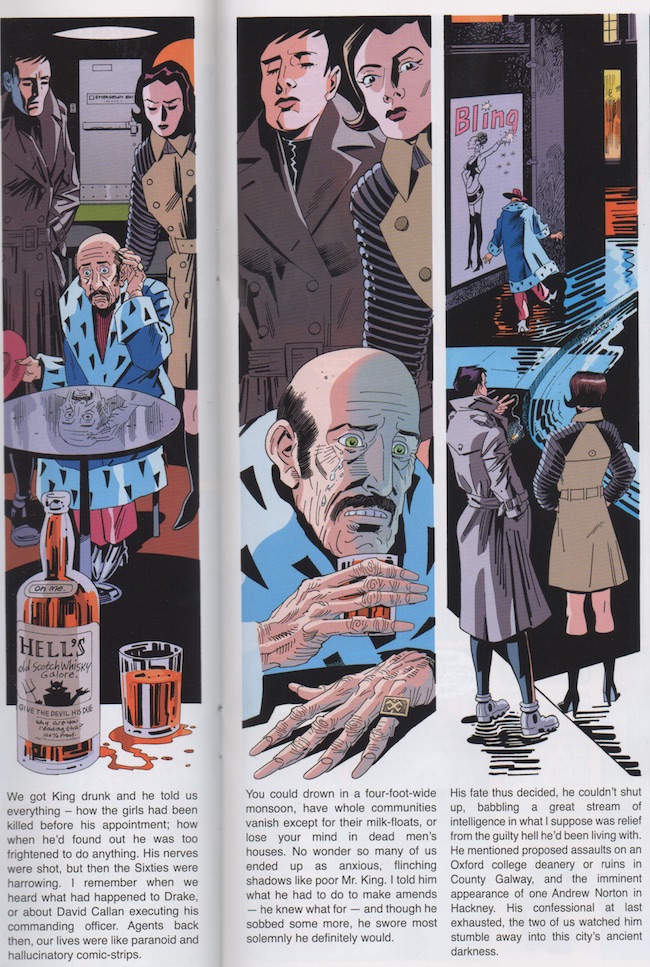

This, however, is how life has felt from 2016 until now: like so much of the citizenry is lying to themselves, believing in multiple conspiracy theories, that consensus reality is essentially irreconcilable, and can only be made sense of by those who are versed in the insane systems of thought that other people believe in. There’s QAnon and Pizzagate on the right, along with the old reliable white supremacist standby of The Protocols Of The Elders Of Zion. When looking into the origins of any of these, one discovers the possibility that the QAnon stuff is prank pulled by the leftists. On the left, there is much infighting over how much to belief is worthy of investing in the narrative of Russian collusion, as opposed to just winning the next election, and further divisions still over how exactly to win an election. Many of the supposedly objective ways in which reality is measured, for instance statistics, are consciously being manipulated for the sake of winning elections. Elected officials then have considerable sway over the narratives we are told, due to the credulity of the news media; many then elect to talk about how the news media cannot be trusted.

I’m talking from a US perspective because that’s what I know; my understanding of UK politics is vaguer but my understanding is its similarly difficult for residents to keep track of, and figures on the left are regularly tarred with bad-faith accusations of anti-Semitism. If the narratives of Thomas Pynchon novels are all about conspiracies of such fractal complexity they degenerate into entropy, Moore’s take on the modern moment is that entropy has overtaken everything, but that there’s still a density stemming from the weight of history.

The main idea of The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen is that there is an overarching narrative universe that all these old stories are fitting inside. What made this kind of a bad idea is that it’s impossible to reconcile all these fictions, as that’s not how they were designed. Moore might have the brain to slot certain parts into something elegant and funny, but here in the real world the rest of us are being driven insane by what are essentially irreconcilable philosophical differences between the stories we live with and what our neighbors are telling themselves. We cannot talk to one another, and for many it feels we no longer live in same universe as people in our immediate families. This is the moment that Moore is speaking to us.

Moore is uniquely qualified to write a story about the role of stories at the end of narrative. He’s of the first generation of graphic novelists: people who saw the endless serialization of superhero comics and realized they were not as satisfying as an actual work of literature due to the lack of endings. He then worked, really hard, in the pages of Swamp Thing, to have enough characterization and thematic heft that story arcs could end in a satisfying way. He wrote "The Killing Joke" with enough self-seriousness it can be read as a final Batman story. He wrote “Whatever Happened To The Man Of Tomorrow” after being enlisted to conclude decades worth of Superman stories, a universe of self-referentiality, and made something touching using decades of material containing wild tonal variation built around a core of self-referentiality never intended to cohere as a singular work. That was over thirty years ago, and since then, his own narrative has been taken away from him, in multiple ways. Literally, stories he’s written have been taken away from him, work he created with the intention that it would belong to him has had its meaning compromised by a corporation’s seeing greater potential for profit in franchised garbage than it does in work of literary merit.

At the same time, there’s a younger generation of fan that sees these valid complaints and then dismisses Moore as an old man, pointing to the preponderance of sexual violence in Moore’s work as the fetish of a lech, and the appearance of a weird archaic racial caricature in The Black Dossier as indicative of someone out of touch with enlightened attitudes. These two things coincide in that DC is then able to pinkwash the theft of Moore’s intellectual property by having the first appearance of Promethea in an issue of Justice League be written by an openly gay creator who performs the important-for-representation’s-sake duty of writing The Midnighter, a gay and more violent analog for Batman that became a DC property through the same corporate merger that arguably acquired Promethea. (I say arguably because it seems like it’s specious ground that Moore just doesn’t have the willpower to litigate over.)

Tom Strong appeared in a series called The Terrifics, written by Jeff Lemire, who maybe is viewed as having some “indie cred” from having originally written and drawn graphic novels published by Top Shelf. Honestly, I don’t know how the creators of these books justify or excuse their involvement and still consider themselves “good people” or members of a community of artists. I am sure they, after having been given the task of integrating Moore’s creations into DC continuity by their editors, would profess to be fans of Moore, despite the readily apparent facts making such claims seem deeply insincere. It’s like learning Pete Buttegieg wrote a high school paper about Bernie Sanders: you can be aware of a lot of stuff in your youth without necessarily learning anything from it, I guess.

There are plenty of reasons for Moore to be bitter about the mainstream comic book industry. The one I most want to call your attention to now is that the mainstream comic book industry is a metonym for larger trends within American culture. The diversity on offer is superficial, with much sharing the same hollow and empty core, in love with violence and empire, indifferent to anything outside increasing its share of the market, as the resources needed for something sustainable in the long term deteriorate. There’s a glut of product so there is no way to be aware of what might truly be good or transcendent, there is just something niche-marketed to atomized individuals, to play off their smug self-satisfaction, whether they want to be flattered for their superficially clever and earnest-approximating aspects, or just have their lizard brain stoked by sadistic cruelty towards an imagined other. The corporations that own these characters have been able to capitalize on their decades of exploitative labor practices, by seizing on strains of nostalgia in our culture, and scaling up the spectacle using the added budgetary boost afforded by partnering with the ever-profitable American military.

If it is a “shared universe” that unites the stories being told in Iron Man and Thor movies, so too is there a shared moral universe that unites Marvel and DC, and the dominant voices in major political parties. It’s one that values power, and this is not the world Moore occupies. The stories they tell hope to create a simplistic gloss of “good vs. evil” over the play of disparate groups jockeying for power and uneasy coalitions. The story that Moore needs to tell is a different one. It is not about the psychology that motivates the electorate and their representatives, but it does understand that psychology to be a fraught mess. Everyone involved has a different framework they’re approaching things with, and these are in conflict with one another for multiple reasons, not the least being that many of them are completely deranged. This is depressing on a lot of levels but it also heaps absurdity atop absurdity, and so while times have never been darker and the stakes are incredibly high, almost everything being said by anyone with any degree of power is very stupid all the time now. So it follows that The Tempest often does not seem to drive itself forward using a logic based in realistic characterization or mimetic naturalism. It is written in a register closer to the humor strips Moore wrote in his Tomorrow Stories anthology than it is to From Hell. Tragedy is repeating itself as farce, and Moore knows the material he’s parodying far better than Donald Trump knows Ronald Reagan’s presidency.

The two most recent interviews of Moore’s I’ve seen support the notion that his current work should be read as a political project: He interviewed the writer Jarett Kobek for a Youtube video, wherein Kobek talked about his new book, where an author’s attempts to write a fantasy novel give way to tormented complaining about the overwhelming state of the world. Talking about the impossibility of telling a story at this point in time, Moore nodded in agreement, even though The Tempest does satisfy as a narrative in a way I assume Kobek’s text is disinterested in. A few days before the final issue shipped to stores, Moore appeared on the podcast Chapo Trap House, a show whose political concerns basically correspond to the complaints about milquetoast centrist punditry I’m offering now.

I do not wish to ascribe my politics to Alan Moore’s, or suggest his politics align with whoever is farthest left in any given election. Moore is an avowed anarchist, which my own instincts come closer to every few months or so, as representative democracy seems increasingly like a sham, with the system of checks and balances a premise given the barest lip service, as we wait for elected officials to behave heroically while every transgression against democratic norms is treated as an enticement for the audience to wait for the next exciting installment of The Voting Process. I grow tired of it the way I grew tired of reading monthly superhero comics, after one too many instances of feeling I had read the same story the month before. Every election is called the most important of our lives, the way event series are sold as the one that will change everything. To quote the rapper Aesop Rock talking about therapy, “I’m reminded it’s a racket, not a rehabilitation.”

Moore has attempted to walk away from the worst aspects of the comics industry before, and his latest attempt has him bidding goodbye to the medium altogether.

IV. The Cartoonist, The Writer, His Wife, And Her Influence

This volume is titled "The Tempest", after Shakespeare’s final play. Moore has stated he plans on this being his final comic, and the title alludes to this parallel between the two works. The title also points to the prominence in the story of the character of Prospero, a wizard who originates from the Shakespeare play but who’s been a presence in The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen since 2007’s The Black Dossier. The character, in the League, seems at least in part a stand-in for Moore, with his well-publicized interest in magic and long beard.

In the League series, Prospero is a resident of The Blazing World, which is the realm of explicit magic, fairies and whatnot. The larger world of the book is the world of literature, so that stuff, with its separate rules, needs to occupy a different level of reality, essentially. The Blazing World is depicted in stereoscopic 3D, glasses are enclosed in both The Tempest and The Black Dossier, and residents of these realms are depicted wearing similar eyewear. Reading a 3-D comic is pretty difficult, for me and I assume for others, because of the way the eyes move during the reading process to take in text. From The Black Dossier on, basically, the density of the reading experience vibrates in the brain in a similar way, as if the hemispheres of the reader’s brain are taking in the content of the page from slightly different angles. The eye strains during the 3D segments; the brain strains throughout.

The degree of difficulty decreases if you reread the volumes you may recall as somewhat tedious. The Tempest is a much more fun reading experience than The Black Dossier or Century. There is a fine balance the series strikes between creating a space referencing and reconciling all the stories it speaks to and telling a satisfying story in its own right, if those volumes read as being too much of the former, it helps now to remember what the story being told it was easy to lose track of was because threads of it are being woven together now.

Still, if the Shakespeare reference in the title didn’t warn you that you’ve got to have some fondness for the high-minded and intellectual for this comic to be for you, let me mention another “not for everyone” artist it’s fair to keep in mind. Shakespeare’s The Tempest was also the basis for Peter Greenaway’s 1991 film Prospero’s Books. Peter Greenaway’s work has a sort of fussy structuralism which impresses on an intellectual level even when it is visceral and pervy. His genius seems similar to Moore’s and, standing apart from the rest of the world, off on a frequency of his own, seems a likely source of inspiration. Moore’s capability of a comparable level of forethought suggests his self-imposed distance from the internet has suited him well: his brain has not melted, or become addicted to its own distraction.

I know it’s considered uncouth to assert internet addiction is bad for the brain, because so many young people were born with it in their blood and cannot imagine willingly going through withdrawal. It might be okay for people to accuse older people of becoming brain-damaged through exposure to social media, however, because of assorted generational differences that make baby boomers a target for scorn. I’ve already discussed the elements in Moore’s work younger fans deride, but it’s notable that the comics Moore loves, that are in his DNA, are pretty unfashionable at the moment.

Moore was born a decade after Robert Crumb, and his commercial success has no doubt allowed him to smoke more weed than any underground cartoonist with whom he shares a veneration for Harvey Kurtzman’s MAD. Despite his work’s formality, it’s clear on some level he aspires to the anarchism of the undergrounds. To the best of my knowledge, the only times this century Moore has offered blurbs of endorsement to comics published by DC, they were drawn by Richard Corben. Aside from Kevin O’Neill, the collaborator Moore has the longest yet-unsevered relationships with would be Rick Veitch and Melinda Gebbie, people whose first published work appeared in underground comics. O’Neill doesn’t come from that world, but his work was infamously denied Comics Code approval in the eighties based on how gnarly it was. He’s an ideal collaborator for Moore, in that his compositions maintain clarity, while the linework itself possesses not just “rough edges,” but seems to maintain a layer of filth and grime that will infect whatever they cut.

I don’t mean “rough edges” in the sense of “weaknesses in the art,” although there are a lot of characters in this thing, and definitely not all of them are immediately recognizable. I’m talking about main characters, even, not just the cameos. You can work it all out from context, it’s just a complicated read, with a lot of moving parts. O’Neill is called upon to do a lot here. I assume he directed the photographic sequences. He does big cutaway maps, sequences in comic strip format, assorted little bits of business in homage to bits of comics history. If you’re a fan of comics as a medium, or have grown up reading them, there is plenty here that will delight you; he’s playing the hits. His line may always feel stiff and affected at a certain level but it’s capable of doing anything, and tells its jokes in a deadpan manner.

O’Neill has his own body of work worth considering in dialogue with this book. When the series was announced, it was easy to think of his work in association with the Victoriana premise. He’s great with pen-and-ink, capable of hatching with a level of detail that can call engraving to mind engraving. However, much of that effect was lost in the reduction from the art’s original size and the added layer of computer coloring. Now, the book is no longer set in the 19th century, and the art feels determined both by a sense of internal consistency and a skill with humor. Prior to illustrating the series, O’Neill would be best known to American readers for his work on Marshall Law, a superhero parody far darker and meaner than what we get here. British readers would know O’Neill from his work on 2000 AD, which the last issue is designed to resemble.

If we’re thinking of Moore in terms of theater and drama, we can think of the structuralist literature professor and the underground humor cartoonist as characters in conflict. O’Neill’s art is the manifestation of that humor, though paradoxically, in a theater context, he then functions as the straight man, in that he bounces off all the high-minded manipulation and takes it at face value. Or to go back to the Greenaway comparison, his is the scenery-chewing acting of a Michael Gambon, that does the necessary work of taking everything high-minded and making it immediate. If he seems maybe a little exhausted, this should be forgivable. This metaphor where the human element is buffeted about by larger forces is not just a description of a comic book collaboration where an artist illustrates a complicated script: it’s the story of our era.

While our moment can be accurately described as chaotic, based on how it feels, the problems we face are long-standing ones that have only built on themselves to bring us to now. I talked electoral politics before, but that is really only the portion of the present that allows for the possibility of hope: There are a great many things I’m worried about the ramifications of that no one has begun to address: the way education shifts its focus to the STEM fields because those fields do not want to do the work of paying for the training of its workers offloads higher and higher expectations for math knowledge onto younger and younger children, the number of schools with either strict discipline or instruction led by computer programs increasing, despite experts in child brain development believing the importance of school and play being to teach empathy and social skills, children who then lack these qualities growing into alienated adolescents who fall into weird online wormholes that prey on the emotionally disengaged to radicalize them with inhuman ideology, having being funneled into this by algorithms that push the content favored by those who spend the most time online, creating an awful world everyone can wash their hands of the consequences of as it happens largely automatically and algorithmically.

The dread this creates is the opposite of what a conspiratorial worldview supposes: it doesn’t postulate a cabal that orchestrates evil, but points to a series of essentially unrelated cultural circumstances that converge with one another to exponentially increase the damage done by their individual effects. If conspiracies are comforting because they’re a narrative where bad actors have agency, and can perhaps be overcome if they are exposed, now it feels more like people with good intentions are hopeless to change the effects already in motion. You might be familiar with this feeling from the cliffhanger at the end of issue 11 of Watchmen.

V. We Tell Ourselves Stories In Order To Live, And Laugh That We May Not Weep

While The Tempest in Shakespeare’s play is unleashed in the first act and sets the plot in motion, here it comes at the climax of the narrative. It is a storm of fictions. The world is overcome by all the fantastical premises that would destroy the psyches of those who’d be forced to endure them, all the Martian invaders and vampires and ape-human hybrids. Many of these forces are specific references to works I’m unfamiliar with and could not attempt to guess.

This is set in motion by Prospero, but the League has unknowingly colluded. Moore is offering a criticism of his whole project, in the League and elsewhere, as a creator of the fantastic. In the past, the primary antagonist of the series has been the military, intelligence agencies, pragmatists, “realists,” imperialists. This thread is present in the early issues of this series as well, but what truly dooms the world, after nuclear disaster is averted, is our old friends, the fictions. Implicit in this is Moore reconsidering the role of the fantastic in human life. Before, he viewed it as an inspiration that brought out our better selves. Science fiction inspired great achievements, while witches and fairies were meant to remind us of our ties to the natural world through the folklore of the past. Now superheroes dominate the culture, our times are at their bleakest, and things need to be reconsidered.

Moore and O’Neill have been working on The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen, on and off, for twenty years. It took less time than that for Moore to feel bad about the negative influence his eighties work had on the comics medium. He’s ending his career on a note of self-critique, which is emphatically not the criticism other people are making of him. Moore is critical of the way his own work has been used, how his radical vision was compromised by the corporate intermediaries that paid him. If The Black Dossier ended up extolling the virtues of the imagination, and got criticized for the use of a racial caricature to symbolize imagination, this later work highlights that imagination in itself is not necessarily virtuous, and to extol escapism as a value is as nihilistic as a rigidly materialist approach to realism. Traditionally, this has been the enemy of the book, as exemplified by James Bond and his misogyny, or the military and its ends-justify-the-means pragmatism justifying cruelty.

However, in the end, Moore maintains an attitude of “fuck you if you had a problem with the racial caricature,” by bringing the character of the Golliwog back essentially because he knows the audience hates it, and he wishes to parody the presentation of sentimental pablum as something that would satisfy fans. It ends, like a Shakespearean comedy, in a big marriage scene, taking place between characters readers have no investment in at all, and the Golliwog sits in the front row. Moore is unapologetic about his use of the character because, I think, he views the discussion about it as distracting from his intent, and his intent is for the work to not just be seen as a distraction.

Moore is interested in questions about the past and what we preserve from it. Clearly, there are things from the 19th century he thinks are interesting, but I don’t think he’s primarily a nostalgist. For a while, obviously, he was interested in the fact that much work from that era serves as a predecessor to the superhero genre, but I suspect that if anything that serves as a mark against that work now, and if he’s interested in anything, it would be the psychological portraiture and nuance of who we are as humans that has remained unchanged. If Moore were maintaining a museum of historical exhibits, which in some ways is what the series is, the original premise would be an exhibit he now wants to rotate out.

One of the major plot points in this series is that a character, Satin Astro, had travelled back to 1964, to join a superhero team, with the hopes of averting the future disaster that comes into being in the 21st century. I mentioned before that the fake letter pages in every issue were similar to Moore’s series 1963, this plot point is similar as well. The Tempest feels like a spiritual sequel, with the addition of an actual conclusion, to the work, although it takes a few panels to lament it’s not finishing the work Moore began on Big Numbers instead.

Moore’s work always has a sense of meaning behind it. He’s both a holdover from the era when children actually read comics, and someone who seemed OK with the idea of providing moral instruction to the adolescents and adults who might be out there. This included lessons in anarchism and the occult, because those were what worked for him. The funny thing about The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen series is, because so much of it is about literature, there’s an element of parsing meaning that has got to come down to aesthetic preference at a certain point. I think a lot of readers were done with the series, and Moore, after the Century volume which culminated with a confrontation between Harry Potter and Mary Poppins. It might have come off as a little petty, as something of an overreaction. It’s interesting to wonder why Moore considered Mary Poppins emblematic of good and derided Harry Potter as the anti-christ. Without offering any opinion on the works’ respective quality as literature, it’s worth noting that Moore basically stands in solidarity with anyone whose creative work was stolen and exploited by the Disney corporation, and views those who can actually profit off the fantasies they sell to children, and developmentally-arrested adults, with suspicion. Don’t forget: Batman was “created by Bob Kane,” ostensibly, as Kane was one of the few who worked in the industry who was successfully able to game the system in a way where he got credit for work he didn’t do. The Tempest includes brief biographies of British cartoonists the industry mistreated. Any satire about superhero comics is tempered by a respect for people who worked on them. Much of his meaning here stems from his own sense of meaninglessness. His solidarity with these forgotten figures extends to his own vision of himself now. He’s an old man, in a better financial state than most, but still not as successful as he’d theoretically be if he owned more of his work. Moore’s aware the audience has moved on, with many of them preferring Harry Potter, and he will not be listened to. He’s shouting into the void. There, once forgotten, characters and creators coexist equally, as abstractions.