Seth Lipsky sat at a table at the Harvard club, a round, avuncular 67-year-old in a proper suit and tie, and uttered a preposterous claim. “The Forward won the Cold War,” he said, referring to the Yiddish-language newspaper edited by the subject of his new biography, Abraham Cahan. “And when I say that, people tend to laugh, but it’s true,” Mr. Lipsky added, a silver-knobbed cane resting by his side. “The Forward was one of the first pro-labor socialist institutions to turn against the Communists in Russia.”

Whether or not we believe the entirety of Mr. Lipsky’s claim is beside the point. That he should make it is, at base, a testament to his faith in the power of newspapering, of which Mr. Cahan was a master. He established The Forward, one of the first national newspapers, in 1897, publishing editorials and advice columns that defined Jewish life for generations of immigrants. Mr. Lipsky sought to channel his predecessor’s intrepid spirit when he launched the English-language edition of The Forward in 1990, leaving behind a nearly 20-year-long career at The Wall Street Journal to run his own ship.

“He really was one of the great progenitors of modern journalism and a newspaper editor in the way they’re supposed to be, as historical actors,” Mr. Lipsky said. “They’re players on the world stage, and newspapers are their instrument.”

Mr. Lipsky, a virtuoso editor, could very well have been talking about himself. Although he no longer runs a newspaper—he left the weekly Forward in 2000 and went on to found The New York Sun, the scrappy daily broadsheet that folded in 2008—his presence is felt in the scores of esteemed writers he published.

In fact, it’s hard to imagine what the past quarter-century of journalism in New York would look like without Mr. Lipsky’s estimable footprint. The list of Lipskyan alums is long and varied and includes the likes of Jonathan Mahler, Philip Gourevitch, Jeffrey Goldberg and Ben Smith.

In fact, it’s hard to imagine what the past quarter-century of journalism in New York would look like without Mr. Lipsky’s estimable footprint. The list of Lipskyan alums is long and varied and includes the likes of Jonathan Mahler, Philip Gourevitch, Jeffrey Goldberg and Ben Smith.

“He changed all of our lives—that’s very clear,” said Mr. Goldberg, a columnist for Bloomberg View and a national correspondent for The Atlantic who worked for Mr. Lipsky at The Forward. “He was the essence of an old-fashioned newspaperman.”

Mr. Lipsky’s editorial wizardry encompassed some fairly eccentric demands. He encouraged his reporters to smoke, for instance, and, in his early days at The Forward, required that they wear fedoras when conducting interviews.

“He told me that to look like an adult I needed either a suit or a beard,” said Mr. Smith, the editor in chief of BuzzFeed who was an intern at The Forward under Mr. Lipsky and went on to work for him as a staff reporter at The Sun. “I’m often the only person at BuzzFeed in a suit.”

Mr. Lipsky’s aims were not merely cosmetic. “What he was interested in was people taking things seriously,” said New Yorker staff writer and former Paris Review editor Mr. Gourevitch, a Forward alum. Mr. Lipsky gave his reporters free range to do their work. When conflicts arose, he always backed them up. And scoops were the priority.

“Seth would pace around the newsroom, saying, ‘I want scoops!’” said Ira Stoll, who worked for Mr. Lipsky at The Forward and followed him to The Sun to be the paper’s managing editor.

“Working for him was like graduating from a school,” said Jonathan Rosen, who was culture editor of The Forward during Mr. Lipsky’s tenure and is now the editorial director of the Nextbook publishing series, which put out Mr. Lipsky’s latest book. “People have gone on to larger places, but I’m not sure anybody felt the calling was higher or the stakes mattered more.”

THE STAKES HAVE ALWAYS been high for Mr. Lipsky, a lifelong journalist who was weaned on the Cold War. Raised in a secular Jewish family in Great Barrington, Mass., he graduated from Harvard in 1968 and went on to work at The Anniston Star, an anti-segregationist newspaper in Alabama. He was drafted into the U.S. Army and sent to Vietnam, where he served as a combat reporter for Pacific Stars and Stripes.

He joined The Wall Street Journal shortly after the war, doing stints in Detroit, Hong Kong, Brussels and New York, where he worked on the editorial page for four years under Robert L. Bartley, a mentor and leading conservative voice during the Reagan years who memorably quipped that “it takes 75 editorials to pass a law.” (Mr. Lipsky helped found the Asian and European editions of The Journal as well.)

Mr. Lipsky had intended to spend the rest of his career at The Forward but was forced to resign in 2000 for his stridently right-wing views, which the owners thought ran counter to the paper’s leftist roots—and, thus, Mr. Cahan. (In an infamous editorial, Mr. Lipsky proposed that the United States bomb North Korea’s nuclear weapons facilities, which infuriated the literary critic Alfred Kazin.) Many reporters, loyal to their editor, left The Forward in solidarity after Mr. Lipsky was ousted.

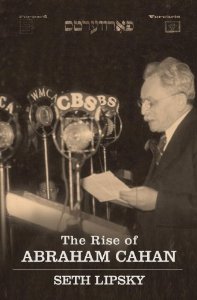

A central component of Mr. Lipsky’s new book, The Rise of Abraham Cahan, is that its subject, who was more hawkish than many remember him to be, has been misinterpreted by his admirers. “If you go back and read the editorials that he wrote, it’s like the John Birch Society,” said Mr. Lipsky, who describes himself as a neoconservative, a term applied to Mr. Cahan as well. “I mean, they just were really, really anti-communist.”

As it happens, Mr. Lipsky is devoted to many of the same causes Mr. Cahan took up in his time, including Zionism (which Mr. Cahan got behind later in life) and the struggle against Communism. Mr. Lipsky can be quite savage in his views, which have gotten him into trouble not only at The Forward but also The Sun; many readers saw the daily broadsheet as a mouthpiece for the conservative cause. Yet one gets the sense that his greatest cause is newspapers themselves, as instruments of democracy and vehicles for informed opinion, whatever the opinion may be.

“We have this consolidation into one or two newspapers nationally,” Mr. Gourevitch said. “And I think Seth sees that not as a loss to a profession but to a country.”

When Mr. Lipsky founded The New York Sun in 2002, there was an air of excitement as he endeavored to resuscitate the legendary broadsheet. (The Sun had been published in New York from 1833 to 1950 and may be best remembered for its “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus” editorial.) “The daily frequency was important to me,” he said. “I think, to really get the kind of horsepower you want, you need that daily frequency.” New York Newsday, the last Manhattan-based daily to enter the fray, had shuttered in 1995 after a decade-long run, losing $100 million. People wanted to see if The Sun could prove history wrong.

The paper positioned itself as a local competitor to The Times, managed to break news and quickly became known for its glaringly conservative editorials, one of which endorsed Dick Cheney for president. But it was perhaps most highly regarded for its excellent coverage of the arts, which Mr. Lipsky has always valued. (He serialized Maus II while at The Forward, which was also known for its culture pages.)

Regarding The Sun’s arts bent, “there was a need for it, because the News and the Post don’t do anything for the arts and The Times had become predictable,” said the culture critic Gary Giddins, who reviewed DVDs for the broadsheet. He was so shocked by the right-wing tone of the A section that at first he thought twice about contributing to the paper. Eventually, though, he softened. “Conservative or not,” he said, “I was really rooting for it, and I just hoped that they would go on and on and on.”

The paper, whose inauspicious run was bracketed by the Sept. 11 attacks and the financial meltdown of 2008, got by primarily on the financial largesse of conservative backers but failed to make a profit (as did The Forward). It ceased publication after seven years in print.

A NEWSPAPERMAN without a newspaper, Mr. Lipsky is nevertheless keeping busy. He is working on a second book about the Constitution, whose tenets he has spent his life defending. (The first was The Citizen’s Constitution: An Annotated Guide.) He writes regularly for The Journal, The New York Post and The American Spectator. He has long been an amateur painter. He is trying his hand at novel writing. He says that, if things ever fall into place, he would like to develop his online version of The Sun—on which he still publishes a trickle of editorials, guest columns and pieces on art—into something more viable.

“I’m watching what’s happening in the Web industry, and, at some point, an approach will come into focus for me that’s worth taking to an investor,” Mr. Lipsky said.

“But I don’t want to lose the money of investors,” he added with an air of gravity. “I don’t want to do that.”

When asked if he might attempt to revive the print brand, Mr. Lipsky said it would be challenging, which is not to say impossible. Sustaining it would be a different story.

In the meantime, there are lessons to be drawn from Mr. Lipsky’s latest book, which is not only a biography but a vivid snapshot of a particularly robust period in the history of American journalism.

“At a time of turmoil within the newspaper industry, it’s a reminder that, at the end of the day, it’s not about process—it’s about the stories you’re coming in with and world events and the great struggle,” Mr. Lipsky said. “You don’t want to win the struggle in order to work for a newspaper. You want to work for a newspaper in order to win the struggle.”