Venezuelan squatters bank on the future in office tower

- Published

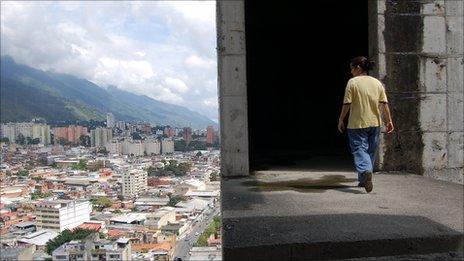

Living the high life in Caracas - not for the faint-hearted

The views from the 20th floor of the Confinanza Tower are among the most spectacular in Caracas, reminiscent of those from an expensive penthouse apartment.

But the homes being built in this high-rise building, which actually goes up another 22 floors, are not expensive apartments. They are the kind of breeze-block shacks found in the city's hundreds of shanty towns.

This is perhaps the most curious skyscraper in Venezuela, being one of the tallest squatter buildings in the world.

Isabel Morales is still haunted by the latest tragedy to happen here.

"A little girl fell 18 storeys to her death," she recalls, shuddering slightly.

"The neighbour who was looking after her only took her eyes off her for a minute. God only knows..."

Her words trail off as she nods towards her own three-year-old son, who is charging around their incomplete, brick shack, playing with a toy truck.

She has good reason to worry. Behind her is a gaping hole in the floor. She and her husband have boarded it up as best they can, but she must be constantly vigilant in case the child climbs over their makeshift barrier. There is a sheer drop of several floors onto the concrete below.

These are the daily risks being run by some 700 families who live in this extraordinary skyscraper in central Caracas.

Buzzing with activity

Torre Confinanza was never meant to be lived in. In the early 1990s, it was going to be a bank. One of the tallest office blocks in Latin America, the bank that owned it went bust in 1994, and the semi-completed building passed into state hands.

Alexander Daza pins his hopes on negotiation

There it languished for more than a decade, gradually deteriorating and becoming a haven for drug-addicts and prostitution.

But today the building is again abuzz with activity and construction. Three years ago, hundreds of families who could not find decent homes elsewhere in the capital descended on the derelict building and started setting up their houses.

Little by little, they have built small, brick homes on more than half the building's floors. Isabel's house is inside the multi-storey car park.

"I came here from the Andes in search of work and a better education for my children," she says, adding that despite the risks, she considers the tower to be her best option in Caracas.

"We have built a space where we can live in peace and harmony," community leader Alexander "El Nino" Daza tells me. "We don't want violence, or drugs, or bloodshed, none of that."

The violence of Caracas is something he knows well. Mr Daza is a former gang member who became an Evangelical pastor after turning to religion in jail.

Three times a week, he leads other members of the community in prayer and song as they give thanks for the space they live in. He shows me the new church that he and the other followers are building.

"We're not stealing anything. We pay for the electricity and the water legally. Every family must pay around $15 (£10) a month to live here in order to pay for the things the community needs.

"We're trying to do everything through the proper legal channels so that if the government ever tries to throw us out, we'll have the paperwork ready," he says.

Planning objections

The government says it is working with the community to try to find a solution, and Mr Daza says that most families inside the tower support President Hugo Chavez. They are confident that the issues raised by living in the former bank can be resolved through negotiation.

But some residents of Caracas do not believe it is responsible to let the families simply convert the skyscraper into homes.

"For me, it's a symbol of anarchy, a symbol of a lack of government and of public inefficiency," says Sulemar Bolivar, who sees the building every day from her office, as head of urban planning for the mayor of Caracas, Antonio Ledezma, who is a member of the opposition.

Many residents carry out their own building work in the tower

"It's like rewarding the man who steals because he's hungry. No? Their act of invasion was not justified," Ms Bolivar argues.

"There is a housing deficit of more than 400,000 homes in Caracas, not to mention those who live in homes which are unfit.

"If the government chooses to give these people that building, there must first be a proper process of refurbishment involving the fire service and other public bodies. It cannot be simply handed over without proper consultation," she says.

Ms Bolivar also believes that more should have been done by previous administrations. "There are several other buildings like this in Caracas which are also a result of the banking crisis in the 1990s.

"When they passed into state hands, they should have been auctioned off. That would have generated much more for the city including more employment and new housing," she says.

Back at the Torre Confinanza, there are no working lifts, so young men and women are carrying building materials up dozens of hastily-constructed concrete staircases, with no handrails on either side.

Construction work without a hardhat or harness 20 floors up is not for the faint-hearted or vertiginous.

But further tragedies like the young girl's death may prompt the authorities to step in, risking an angry response from the families who have made the former bank their home.

- Published15 November 2010