In the academic discourse, there is a noticeable preference for the utilization of textual sources, rather than non-textual sources, such as material artifacts, photographs, oral histories, etcetera. As a student of archaeology, I recognize the myriad insights that can be gleaned from studying and analyzing material objects and artifacts, especially for the purposes of developing a fuller comprehension of a people, culture, or time period. I would contend that, in many cases, material objects can provide a more detailed, nuanced understanding of a people, culture, or time period than textual sources and, as such, should be valued and utilized more readily in academia as invaluable primary sources.

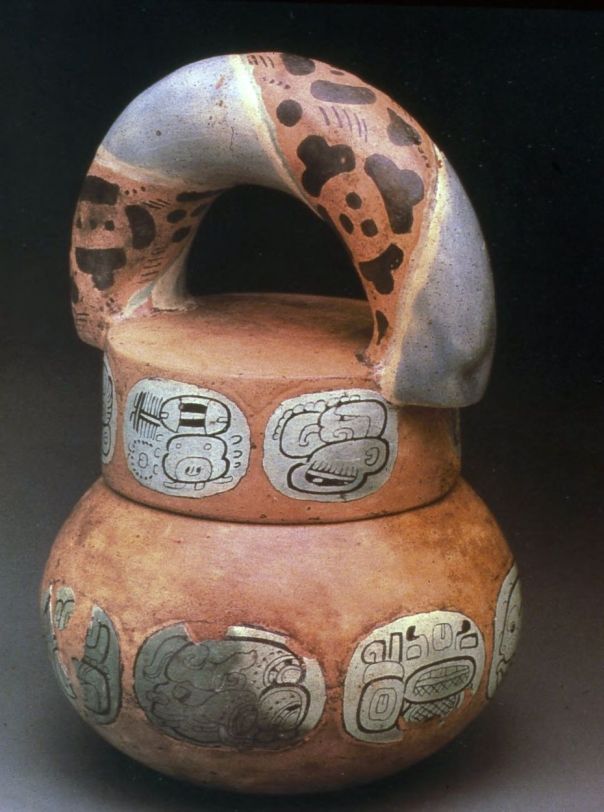

A particularly illustrative case-study, the Río Azul vessel demonstrates the extent to which the close analysis of an artifact can provide keen insights into a people, culture, or time period. Specifically, this vessel illuminates the importance of cacao for the Classic Maya and, as such, serves as an essential tool for reconstructing an understanding of the uses and multivalent meanings of cacao for this cultural group.

The Río Azul vessel features an exterior surface, which has been covered in stucco and adorned with Classic Mayan hieroglyphs. Close analysis of the vessel’s exterior can provide invaluable insights into the Classic Mayan artistic tradition, writing system, artisan class, manufacturing process, etcetera.

The Río Azul vessel features an exterior surface, which has been covered in stucco and adorned with Classic Mayan hieroglyphs. Close analysis of the vessel’s exterior can provide invaluable insights into the Classic Mayan artistic tradition, writing system, artisan class, manufacturing process, etcetera.

Before delving into the insights derived from the Río Azul vessel, it is instructive to first discuss the vessel’s archaeological context. In 1984, archaeologists discovered Tomb 19, a Classic Mayan tomb dating from the last half of the fifth century CE, in Río Azul, a Mayan city in the northeastern corner of the Petén region of Guatemala (Stuart 1988: 153). Within Tomb 19, the corpse of the tomb’s owner, a middle-aged ruler, had been laid on a funeral litter and was surrounded by various objects, including fourteen pottery vessels (Coe and Coe 2013: 46).

One of these vessels, which I will henceforth refer to as the Río Azul vessel, particularly intrigued archaeologists. An extremely rare pottery form, this vessel consists of a wide, bowl-shaped pot and a lid, which includes an arching handle. The pot’s lid possesses a noteworthy “lock-top” feature: the lid can be screwed onto the main body of the pot and, when properly closed, can be held by its handle without any risk of spilling the vessel’s contents. The exterior of the stirrup-handled vessel features stucco covering and large hieroglyphs, which have been brilliantly painted in turquoise blue and earthen tones.

This view allows one to see the “lock-top” feature of the Río Azul vessel’s lid. One can discern the grooves into which the vessel’s lid slid and closed, which prevented the vessel from spilling its liquid contents.

This view allows one to see the “lock-top” feature of the Río Azul vessel’s lid. One can discern the grooves into which the vessel’s lid slid and closed, which prevented the vessel from spilling its liquid contents.

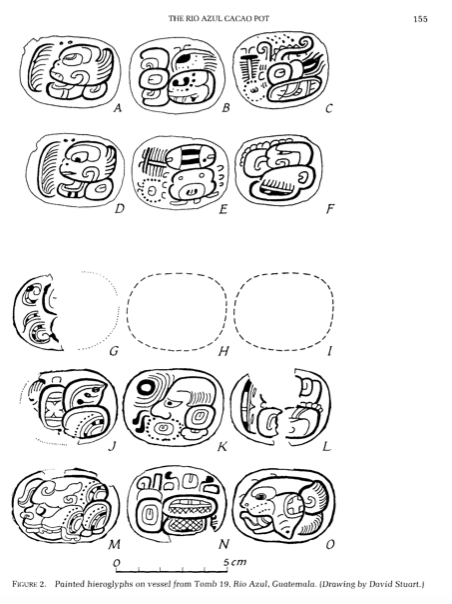

Both the Río Azul vessel’s interior and exterior fascinated archaeologists, who were desirous to utilize the vessel to learn about the Classic Maya. What did the vessel originally contain? Why was it included in a ruler’s burial tomb? What function did it serve in Classic Mayan burial practices? Based on a dark ring around the vessel’s interior, archaeologists hypothesized that the stirrup-handled vessel originally held a dark liquid (Coe and Coe 2013: 46). To determine the exact nature of this dark liquid, archaeologists turned to epigraphy and chemical analysis for answers. The epigrapher, David Stuart, analyzed the vessel’s hieroglyphs and recognized that two of these hieroglyphs represented kakaw, the Classic Mayan hieroglyph for cacao that consists of “a drawing of a fish, preceded by a comb-like sign established by the syllabic glyph ka and followed by the sign for final ‘w’” (Coe and Coe 2013: 45). Stuart’s transliteration of the hieroglyphs—y-uk’-ib’ ta witik kakaw ta koxom mul(?) kakaw—can be translated as “(It is) his cup for witik cacao, (and) for koxom mul(?) cacao” (Stuart 2009: 193). Based on his translation, Stuart posited that the vessel’s dark liquid vestiges belonged to a cacao beverage.

This drawing, which was created by the epigrapher David Stuart, allows one to more clearly see the Classic Mayan hieroglyphs that were inscribed on the Río Azul vessel. Note hieroglyphs A and D, which represent kakaw.

To validate Stuart’s hypothesis, archaeologists sent the Río Azul vessel to W. Jeffrey Hurst of the Hershey’s Company Research Labs in 1987. Using high-performance liquid chromatography to identify the chemical composition of the vessel’s food residues, Hurst isolated the chemicals theobromine and caffeine (Presilla 2009: 10). Since cacao is the only Mesoamerican plant to contain both chemicals, Hurst’s discovery provided “conclusive proof” that the Río Azul vessel was, in fact, a container for a cacao beverage (Coe and Coe 2013: 46).

With its contents confirmed, the Río Azul vessel afforded a wealth of information to academics studying the Classic Mayan relationship with cacao and, therefore, underscores the important contributions that can be derived from studying non-textual sources. For example, the Río Azul vessel served as “the Rosetta Stone” for epigraphists attempting “to crack the whole code of Maya writing” (Presilla 2009: 10). Stuart’s breakthrough—identifying the hieroglyph for cacao—allowed academics to recognize and analyze other hieroglyphic appearances of cacao. As a result of the Río Azul vessel, a single material object, scholarship on cacao received access to additional sources on, and references to, the Classic Mayan relationship with cacao; the Río Azul vessel’s groundbreaking contribution to epigraphy underscores how a non-textual source can provide new opportunities for academic research.

The Río Azul vessel also attests to the myriad uses for cacao during the Classic Mayan period and, therefore, functions as an invaluable tool for comprehending the vast variety of cacao-related terminology and cacao recipes from this period. Specifically, the vessel’s inscription mentions witik and koxom mul, two different types of cacao preparations that do not appear in any other textual or non-textual sources (Stuart 2009: 201). Thus, knowledge of these two types of cacao can only be acquired through the analysis of non-textual sources, a further endorsement for the need to emphasize the importance of studying non-textual sources for their numerous contributions to academia.

As a primary source, the Río Azul vessel also illuminates the Classic Maya’s broader social and artistic culture. The vessel’s beautifully painted and intricately detailed exterior exemplifies the artistic flourishing of the Classic Maya during their Golden Age when they erected magnificent temples and palaces, created stone relief carvings and wall paintings, and delicately painted and carved ceramic vessels, such as the Río Azul vessel. The Río Azul vessel, therefore, typifies the rich artistic culture of the Classic Maya and provides a more nuanced understanding of the period’s Golden Age than a textual source.

Given its archaeological findspot in a burial tomb, the Río Azul vessel also provides compelling insights into the cultural, religious, and sociopolitical importance of cacao during this period. In Classic Mayan burial practice, the deceased were physically surrounded by pottery dishes, bowls, and cylindrical vases that held the food and drink that the deceased was meant to enjoy and utilize in the afterlife (Coe and Coe 2013: 43). The Río Azul vessel’s function as a container for a cacao beverage suggests that the vessel’s cacao contents were intended to sustain the tomb’s owner in the afterlife (Coe and Coe 2013: 43). The Río Azul vessel designates cacao as an essential food for the afterlife and as a valued commodity in both life and death, thereby augmenting the argument that important insights can be derived from studying material objects.

As a final point of consideration, in light of the dearth of written evidence from the Classic Mayan period, the Río Azul vessel merits increased importance as a source for understanding the importance of cacao during this time. Since no textual sources from the Classic Mayan period proper remain, the Río Azul vessel, among other such inscribed ceramics, provides the only primary and contemporary evidence for the Classic Mayan use of cacao; its significant contribution to reconstructing cacao’s significance for the period cannot be overstated.

For its various, important glimpses into Classic Mayan culture and, more importantly, the period’s relationship to, understanding of, and use of cacao, the Río Azul vessel merits the designation as a potent, invaluable source of information. This artifact of stoneware can—and does—speak to the power of archaeological artifacts and other non-textual sources to communicate knowledge and serves as an emphatic call for the greater incorporation and utilization of non-textual sources in the academic discourse.

Textual Sources:

Coe, Sophie D. and Michael D. Coe. 2013. The True History of Chocolate. 3rd ed. London: Thames & Hudson.

Presilla, Maricel. 2009. The New Taste of Chocolate, Revised: A Cultural & Natural History of Cacao with Recipes. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press.

Stuart, David. 1988. “The Rio Azul cacao pot: epigraphic observations on the function of a Maya ceramic vessel.” Antiquity 62: 153-7.

Stuart, David. 2009. “The Language of Chocolate: References to Cacao on Classic Maya Drinking Vessels.” In Chocolate in Mesoamerica, edited by Cameron L. McNeil, 184-201. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Image Sources:

Image after Stuart 1988, Figure 2 (see above for the full article citation).

“Kakaw (Mayan word).” Wikimedia Commons, accessed on March 7, 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kakaw_(Mayan_word).png

“Stirrup lidded vase, from Rio Azul.” Harvard Fine Arts Library, Digital Images & Slides Collection 2004.H06.00848, accessed through Hollis.

“Stirrup lidded vase, from Rio Azul.” Harvard Fine Arts Library, Digital Images & Slides Collection 2004.H06.00847, accessed through Hollis.