In January, I was on the Bowery with Richard Hell, who invented punk rock. We went into an art bookstore on Bond Street and he found a collection of pictures by Richard Prince. After a minute, he jabbed me on the shoulder.

“Check this out!” he rasped, surprised, pointing at the book. It was a picture of Richard Hell, decades ago, wearing the ripped-shirt, short-hair look, his mane black and spiky, smiling with full lips, a crooked nose and purple sleeplessness under his eyes. “I didn’t know this was in here.”

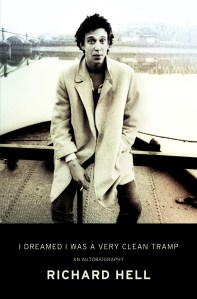

The photograph was taken in the early 1980s, when Mr. Hell still played in the Voidoids, gigging a half a block away at CBGB, the now-gone Bowery rock club largely credited with housing the first yelps of punk. The younger version of himself must have been on his mind, as Mr. Hell has an excellent new memoir, I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp, that describes that wild, reckless and important era in downtown Manhattan with candor, wit and reverence. He and his spiky hair discovered CBGB back when he was in the band Television and began a residency on Sunday nights. Then came the Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads and Patti Smith. The story is not only about rock ’n’ roll, but also about the city experiencing a creative renaissance even as it nearly went bankrupt.

These days, the block by CBGB is stainless and pretty. The onetime beer-soaked punk den now sells fashionable variations on Ramones leather jackets for thousands of dollars. Nearby are luxury hotels, prohibitively expensive apartments and sidewalks clean enough to lick. It’s the only Bowery I’ve ever known, but for Mr. Hell, sometimes, it’s still the New York he once escaped to, the dirty Bowery where he started punk rock.

Richard Hell was born Richard Meyers in Kentucky, but he was not long for that name or that state.

“My favorite thing to do was run away,” he writes on the opening page of Tramp. “The words ‘let’s run away’ still sound magic to me.”

At 17, he hitchhiked down south with a prep school pal and future bandmate, Tom Miller, another misfit who would later change his name to Tom Verlaine. The teenagers made it just across the Florida border. As Mr. Hell recalls their escape in his book, the two friends were in a green world, humid and happy, something almost prelapsarian.

“We didn’t know anybody there,” he writes, “or know anything about the place except that it was warm and airy, and there was plenty of citrus fruit and seafood, and girls who smelled like suntan and had little particles of sand on them here and there, including inside the waistbands of their panties.”

The duo got snatched up by cops and sent back to school, but they would run away together again. Mr. Verlaine eventually joined Mr. Hell in New York, where he was trying to break into the downtown poetry scene (their adoptive surnames nod to those star-crossed Symbolists, Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud, whose first book was called A Season in Hell). Mr. Verlaine had another idea: they’d start a band, with himself on guitar and Mr. Hell on bass. They were first the Neon Boys, then Television, and then Hell stumbled into that dive, CBGB.

The birthplace of punk was a garbage dump. In an unpublished column he wrote during the club’s formative years that is included in Tramp, Mr. Hell says, “the first thing I noticed is that it smelled like dogshit. Then I saw the damned dog.”

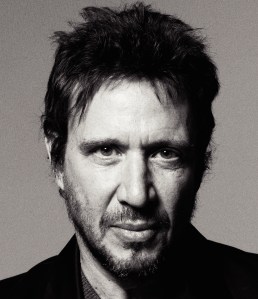

Mr. Hell agreed, after some wrangling, to meet for coffee at The Smile, right by Bowery and Bleecker and not too far from his apartment in the East Village. It’s a faux-rustic spot favored by models and fashion publicists. As we spoke, the Velvet Underground came on. A kid with zippers on his pant legs walked by. Mr. Hell—whose face has changed miraculously little since he was a young man, save for the goatee on his chin—was wearing a nice sweater but still had cigarette burns on his knuckles. No one recognized him as Richard Hell, maybe because he doesn’t dress like a punk anymore, or maybe because no one knew who he was in the first place. And he tended to downplay everything, speaking elliptically.

Mr. Hell agreed, after some wrangling, to meet for coffee at The Smile, right by Bowery and Bleecker and not too far from his apartment in the East Village. It’s a faux-rustic spot favored by models and fashion publicists. As we spoke, the Velvet Underground came on. A kid with zippers on his pant legs walked by. Mr. Hell—whose face has changed miraculously little since he was a young man, save for the goatee on his chin—was wearing a nice sweater but still had cigarette burns on his knuckles. No one recognized him as Richard Hell, maybe because he doesn’t dress like a punk anymore, or maybe because no one knew who he was in the first place. And he tended to downplay everything, speaking elliptically.

“It was an expression of how things were at that moment,” he said, describing the impact of Television, whose first album, Marquee Moon, is perhaps the most hyper-literate of early punk artifacts, a fancily dexterous but punishing record. Having helped forge the group’s downright mathematical guitar playing, Mr. Hell left Television just before the recording of Marquee Moon and went on to form the equally influential, slightly messier band the Heartbreakers. “It wasn’t like we brought something to the world that changed the world, it’s that the world brought us something and we acted on it.”

He was more forthcoming about the impact of his look. Hints of his music can be heard in any band with a guitar today—the raw genius of early Television before Mr. Verlaine kicked him out, the rollicking heroin stupor of the Heartbreakers, the art-damaged menace of his next band, the Voidoids, with whom Mr. Hell dubbed his epoch the “Blank Generation.” But his physical appearance—he cultivated a kind of Truffaut street-rat allure—is at least as enduring a contribution.

“I was amazed, walking by Macy’s in Herald Square, to see ripped-up T-shirts in the windows,” Mr. Hell told me. “That was just three years after I was in my first band, when I was the only person in the world wearing ripped T-shirts.”

In Tramp, Mr. Hell recounts Blondie guitarist Chris Stein showing him a European rock rag with a feature on a new band put together by British impresario Malcolm McLaren, who had booked Television a few shows in New York. Mr. McLaren had always been taken with Mr. Hell’s personal style, particularly how it expressed “alienation and disgust and anger” in the face of hippie love, as Mr. Hell writes. With that in mind, Mr. McLaren went back to England to put together a band called the Sex Pistols.

“Everyone in the band had short, hacked-up hair and torn clothes and there were safety pins and shredded suit jackets and wacked-out T-shirts and contorted facial expressions,” Mr. Hell writes of the Sex Pistols. “The lead singer had changed his name to something ugly. It gave me kind of a giddy feeling. It was flattering.”

The Sex Pistols would quickly cement themselves as the foremost figures of the punk scene, but the debt to Mr. Hell may soon be exposed. When the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art opens its PUNK: Chaos to Couture exhibition in May, the first gallery, the portion devoted to punk’s first rumblings, will be represented by Mr. Hell. He’s also writing a preface to the catalog.

“I kind of assumed I wouldn’t be involved,” he said. “They asked me late, and people totally associate punk with the Sex Pistols. But fortunately, the Met did enough research to know that some of the stuff done by the Sex Pistols was influenced by me.”

If Mr. Hell embodied all of punk’s early promise, he also encompassed its darker side. In Tramp, he recalls his struggles with drugs vividly and without remorse. Though he’s now clean—and the book ends with him finally shuffling to N.A. meetings—this is no recovery story.

“How can I say I regret heroin?” he said to me. “It would be like saying, ‘Wouldn’t you rather be somebody else?’ It’s a meaningless thing to say.”

And anyway, as he puts it at one point, “sex pervades all.” Among the girlfriends he mentions throughout his narrative, all of whom he clearly worshipped, are teenage hookers, French chanteuses, married art patrons, Rolling Stones groupies, Andrew Wylie’s little sister, bassists, the door girl at CBGB and the doomed Nancy Spungen. Many of them overlapped. Men writing about their conquests are often boring; luckily for us, Mr. Hell is a regular Henry Miller when it comes to sex scenes. Take, for example, the following description of coitus with a 16-year-old, in Paris, a tryst that happened while Mr. Hell was waiting for a fiancée, Lizzy, to return from South Africa.

I bent her over the Corbusier. We were in our element. There’s a point where extreme, knowing drug abandon becomes a kind of delicious hell … It’s like a ballet performed at 1/1000 speed and that’s how I put my granite hard-on into Ava and watched her face and watched her lips as she said something snotty and grateful to me, grinning, and meanwhile Lizzy was in the back of my mind and my heart was breaking, drily and brittle though, not as if I had any meaning to lose.

It’s like one of his songs in miniature: the corny hope that two chords and the right words can save your soul.

Mr. Hell, perhaps mercifully, stops his story in the mid-’80s, when he quits music to be a novelist, insisting that “a writer’s life is fairly uneventful.” There is, however, an epilogue, and it concerns what may be the most intriguing thread of the story, one hidden behind the debauchery of beautiful New York weirdos and the rise of a cultural phenomenon: the falling out between two best friends, Richard Meyers and Tom Miller, Rimbaud and Verlaine. In the time since their teenage trips down south, their struggles with words and women in New York and the pioneering of a new type of rock ‘n’ roll, the two have spoken only a handful of times.

“There are people in the book that I’m critical of that I don’t give a shit what they think,” Mr. Hell said of Mr. Verlaine at The Smile. “We don’t have a relationship anymore.”

(A representative at Mr. Verlaine’s record label told me the guitarist had asked him “not to request any interviews regarding Richard Hell.”)

After we left The Smile, he ended up buying that Richard Prince book with his picture in it. We left the store and went back out to the Bowery again.

“Well, you know, actually, it has changed,” he sighed, looking at the scrubbed stretch of Bowery at Bleecker Street. We crossed and stood next to the old CBGB, which now has the name “John Varvatos” printed on its storefront. “I can see people from way back, on this corner.”

editorial@observer.com