鳥類

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2024/03/15 13:54 UTC 版)

解剖学と生理学

ほかの脊椎動物に比較して、鳥類は数多くの特異な適応を示す体制(ボディプラン) を持っており、そのほとんどは飛翔を助けるためのものである。

骨格

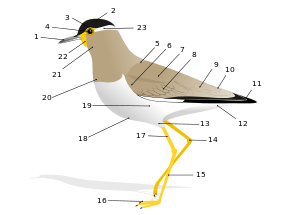

骨格は非常に軽量な骨から構成されている。含気骨には大きな空気の満たされた空洞(含気腔)があり、呼吸器と結合している[73][74]。成鳥の頭骨は癒合しており縫合線がみられない[75]。眼窩は大きく、骨中隔で隔てられている。脊椎には、頸(首)椎、胸椎、腰椎、尾椎の部位があり、頸椎は可動性が非常に高く、きわめて柔軟であるが、関節は胸椎 (thoracic vertebrae) 前部で減り、後部の脊椎骨にはない[76]。脊椎の最後のいくつかは骨盤と融合して複合仙骨を形成する[77]。飛べない鳥類をのぞいて、肋骨は平坦になっており、胸骨は飛翔のための筋肉を結合するために、船の竜骨のような形状をしている。前肢は翼へと修正されている[78]。

消化、排泄、生殖

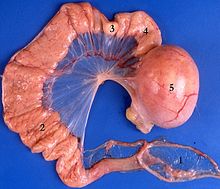

1 漏斗(受精の場)、2 筒部(卵白を出す)、3峡部(卵殻膜形成)、4 子宮(卵殻形成)、5膣(卵が入っている)

鳥類の消化器系は独特である。まず食べたものを一時的に貯蔵するための素嚢(そのう)がある。素嚢の役割は種類によって異なり、食いだめをする種類や素嚢から吐き戻した食物や素嚢から分泌される素嚢乳を雛鳥に餌として与える種類がいるほかダチョウ類のように素嚢を持たない種類もいる[79]。 素嚢に蓄えられた食物は胃に送られるが、胃は前胃と筋胃の二つに分かれている。前胃は腺胃とも呼ばれ、内壁に多数の消化腺があり、消化酵素および酸性分泌物を出す。筋胃は砂嚢(さのう)とも呼ばれ、筋肉が発達しているほか、飲み込んだ砂粒が入っており、この筋胃で食物をすりつぶすことで、歯のないことを補っている[80][81]。ほとんどの鳥類は、飛翔を助けるため、すばやく消化することに高度に適応している[82]。渡りを行う鳥のなかには、腸の蛋白質といった、その体のいろいろな部分からの蛋白質を、渡りの間の補助的なエネルギー源として使用するようになっているものがある[83]。

鳥類は爬虫類と同様に、基本的には尿酸排泄性である。すなわち、その腎臓は血液中の窒素廃棄物を抽出して、これを尿素もしくはアンモニアではなく、尿酸として尿管を経由して腸に排出する。鳥類には膀胱ないし外部尿道孔がなく(ただしダチョウは例外である)、このため尿酸は半固体の廃棄物として、糞と一緒に排泄される[84][85][86]。ただしハチドリのような鳥類は、条件的アンモニア排泄性であり、ほとんどの窒素廃棄物をアンモニアとして排出することができる[87]。さらに鳥類は、哺乳類がクレアチニンを排泄するのに対して、クレアチンを排泄する[88]。この物質は、ほかの腸の産生物と同じように総排出腔から出る[89][90]。総排出腔は多目的の開口部で、排泄物はこれを通して排出され、鳥が交尾するときにはそれぞれの総排出腔を接触させ、そして雌はそこから卵を産む。これに加えて、多くの種がペリット(ペレット、pellet)の吐き戻しを行う[91]。

鳥類の雌性生殖器は、多くの種で生殖時期に左側だけが発達し、繁殖期を過ぎると一時的に退縮し次の繁殖期に再度発達する(左側に何かしらの障害が発生した場合は右側が発達、タカ目など一部の鳥類は両側が発達)[92][93]。

呼吸器

鳥類は、すべての動物群のなかで、最も複雑な呼吸器を持ったグループのひとつである[88]。鳥が息を吸うとき、新鮮な空気の75%が肺を迂回して、後部気嚢に直接流れ込み、これを空気で満たす。後部気嚢とは、肺から広がって骨のなかの気室(含気腔)に繋がっている気嚢のグループである。残りの25%の空気は直接肺に行く。鳥が息を吐くときには、使われた空気が肺から排出され、同時に、後部気嚢に蓄えられていた新鮮な空気が肺に送り込まれる。このようにして、鳥類の肺には息を吸うときにも吐くときにも、常時新鮮な空気が供給されている[94]。鳥の声は、鳴管を使って作り出されている。鳴管は筋肉質の鼓室であり、気管の下部末端から分岐し、複数の鼓形膜が組み合わされている[95][96]。

循環器

鳥類の心臓は、哺乳類と同じく4室(二心房二心室)あり[97]、右側の大動脈弓より体循環が起こるが、哺乳類では鳥類と異なり左側の大動脈弓による[88][98]。下大静脈は、腎門脈系を経由して、四肢からの血流を受け取る。哺乳類とは異なり、鳥類の赤血球には核がある[99][100]。ニワトリの血糖値は210-240mg/dlであり、鳥類は哺乳類に比べて2-3倍の血糖値を示す[101]

知覚

神経系は、鳥類の体の大きさから見ると相対的に大きい[102]。脳において最も発達しているのは、飛翔に関連した機能を司る部位であり、小脳が運動を調節する一方、大脳が行動パターンや航法、繁殖行動、営巣、記憶などの行動を司る。特に、カラス類や、インコ・オウム類は、人間の2〜8歳児ほどの知能を持つと考えられている。

ほとんどの鳥が貧弱な嗅覚しか持たないが、顕著な例外としてキーウィ類[103]、コンドル類[104]およびミズナギドリ目[105]の鳥などがあげられる。鳥類の視覚システムは一般に高度に発達している。水鳥は特別に柔軟なレンズを持つことで、空気中の視覚と水中の視覚を両立させている[106]。なかには2つの中心窩を持つ種もいる[107]。鳥類は4色型色覚であり、赤、緑、青の錐体細胞と同じように、紫外線 (UV) に感度のある錐体細胞を網膜に持っている。これによりかれらは紫外線を見分けることができ、それは求愛行動にも関係する。多くの鳥類は、紫外線による羽衣(うい)の模様を示すが、これはヒトの目には見えない。すなわち、ヒトの肉眼では雌雄が同じに見えるような鳥でも、その羽毛に紫外線を反射する斑の存在によって見分けられる。雄のアオガラの羽毛には、紫外線を反射する冠状の斑があり、求愛行動の際にはポーズを取り、その頸部の羽毛を立てることでディスプレイを行う[108]。紫外線はまた、餌を採ることにも使用されている。チョウゲンボウの仲間は、齧歯類が地上に残した紫外線を反射する尿の痕跡を見つけることで獲物を探すことが証明されている[109]。鳥類のまぶたは、瞬きには使用されない。そのかわりに目は、水平方向に移動する3番目のまぶたである瞬膜によって潤滑されている[110]。また、多くの水鳥において、瞬膜は目を覆うコンタクトレンズのような働きをする[111]。鳥類の網膜は、櫛状体(櫛状突起、pecten)と呼ばれる扇状の血液供給システムを持っている[112]。ほとんどの鳥は眼球を動かすことができないが、カワウのような例外もある[113]。鳥類のうち、目をその頭部の側面に持つものは広い視野 (visual field) を持ち、フクロウのように頭部の前面に両目があるものは、双眼視覚を持ち、被写界深度を見積もることができる[114]。鳥類の耳には外側の耳介はなく、耳羽(じう)という羽毛に覆われているが[115]、フクロウ類のトラフズク属、ミミズク、コノハズク属ような鳥では、頭部の羽毛が耳のように見える房(羽角、うかく)を形成する。内耳には蝸牛(かぎゅう)があるが、哺乳類のような螺旋状ではない[116]。

化学的防御

数種の鳥類は、捕食者に対して化学的防御を用いることができる。一部のミズナギドリ目の鳥は、攻撃者に対して不快な油状の胃液 (Stomach oil) を吐き出すことができ[117]、また、ニューギニア産の数種のピトフーイ(ピトフィ)類(モリモズ類)の数種は、その皮膚や羽毛などに強力な神経毒を持っており[118][119]、これは寄生虫に対する防御と考えられている[120]。

性

鳥類には2つの性別、すなわち雄と雌がある。鳥類の性は、哺乳類が持っているXとYの染色体ではなく、ZとWの性染色体によって決定される。雄の鳥は、2つのZ染色体 (ZZ) を持ち、雌の鳥はW染色体とZ染色体 (WZ) を持っている[121]。鳥類のほとんどすべての種において、個々の性別は受精の際に決定される。しかしながら、最近の研究によって、ヤブツカツクリでは、孵化中の温度が高いほど、雌に対する雄の性比が高くなったことから、温度依存性決定 (Temperature-dependent sex determination) が証明された[122]。

羽毛、羽衣と鱗

羽毛は(現在では真の鳥類であるとは考えられていない恐竜の一部にも存在するが)、鳥類に特有の特徴である。羽毛によって飛翔が可能になり、断熱によって体温調節を助け、そしてディスプレイやカモフラージュ、情報伝達にも使用される[123]。羽毛にはいくつもの種類があり、それぞれが、個々のさまざまな目的に応じて機能している。羽毛は皮膚に付属した上皮成長物であり、羽域(羽区、pterylae)と呼ばれる、皮膚の特定の領域にのみ生ずる[124]。これらの羽域の分布パターン(羽区分布、pterylosis)は分類学や系統学で使用されている。鳥の体における羽毛の配列や外観を総称して、羽衣と呼ぶ[124]。羽衣は、同一種のなかでも、年齢、社会的地位[125]、性別によって変化することがある[126]。

羽衣は定期的に生え変わっている(換羽)。鳥の標準的な羽衣は、繁殖期のあとに換羽したものであり、非繁殖羽 (Non-breeding plumage) として知られている。あるいはハンフリー・パークスの用語 (Humphrey-Parkes terminology) によれば「基本」羽 ("basic" plumage) である。繁殖羽、あるいは基本羽の変化したものは、ハンフリー・パークスの用語法によれば「交換」羽 ("alternate" plumages) として知られる[127]。ほとんどの種で、換羽は年1回起こるが、なかには年2回換羽するものもあり、また、大型の猛禽類は、何年かに1回だけ生え変わるものもある。換羽のパターンは種ごとに異なる。スズメ目の鳥に見られる一般的なパターンは、初列風切が外側に向かって(遠心性換羽)、次列風切は内側に向かって(求心性換羽)[124]、そして尾羽が中央から外側に向かって生え変わっていく(遠心性換羽)[128][129]。スズメ目の鳥では、風切羽は、最も内側の初列風切から始まり、一度に左右1枚ずつ生え変わる。初列風切の内側半分(6番目の第5羽)が生え変わると、最も外側の三列風切が抜け始める。最も内側の三列風切が換羽したあと、次列風切が最も外側から抜け始め、これがより内側の羽毛へと進行していく。初列雨覆は、それが覆っている初列風切の換羽に合わせて生え変わる[124][130]。ハクチョウ類[131]、ガン類、カモ類といった種は、すべての風切羽が一度に抜け、一時的に飛ぶことができなくなるほか[132]アビ類[131]、ヘビウ類、フラミンゴ類、ツル類、クイナ類、ウミスズメ類にもこのような種がある[124]。一般的な様式として、尾羽の脱落と生え変わりは、最も内側の一対から始まる[130]。しかし、キジ科のセッケイ類においては、外側尾羽の中心から換羽が始まり、双方向への進行が見られる[128]。キツツキ類やキバシリ類の尾羽では、遠心性換羽は少し変更され、これらの換羽は内側から2番目の一対の尾羽から始まり、そして一対の中央尾羽で終わる。これによって木をよじ登るのための尾羽の機能を維持している[130][133]。営巣に先立って、ほとんどの鳥類の雌は、腹に近い羽毛を失うことで、皮膚の露出した抱卵斑を得る。この部分の皮膚は血管がよく発達し、鳥の抱卵の助けになる[134][135]。

羽毛はメンテナンスが必要であり、鳥類は毎日、羽繕いや手入れを行い、かれらは日常の9%前後をこの作業に費やしている[136]。くちばしは、羽毛から異物のかけらを払い出すだけではなく、尾腺からの蝋のような分泌物を塗ることにも使われる。この分泌物は羽毛の柔軟性を守り、抗菌薬としても働き、羽毛を劣化させる細菌の成長を阻害する[137]。この作用は、アリの分泌するギ酸によって補われているとされ、鳥類は羽毛の寄生虫を取り除くために、蟻浴として知られている行動を通してこれを得ると考えられている[138]。

鳥類においては、羽毛が紫外線の皮膚への到達を妨げている。鳥類は、皮膚から皮脂を分泌し、羽毛を羽繕いすることによって口からビタミンDを摂取しているとの説もある。この説は毛皮を有する哺乳類にも該当する[139]。

鳥類の鱗(うろこ)は、くちばしや、鉤爪、蹴爪と同じくケラチンから作られている。鱗は主に趾(あしゆび)や跗蹠(ふしょ)に見られるが、種によっては踵(かかと)のずっと上の部位まで見られるものもある。カワセミ類やキツツキ類を除いて、大部分の鳥の鱗はほとんど重なっていない。鳥類の鱗は、爬虫類や哺乳類のものと相同性であると考えられている[140]。

- ^ “Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Taxon: Class Aves”. Project: The Taxonomicon. Universal Taxonomic Services (2014年1月26日). 2014年6月21日閲覧。

- ^ a b 岩波生物学辞典 第4版、928頁。

- ^ a b 広辞苑 第五版、1751頁。

- ^ a b c 『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)、552-553頁

- ^ a b “IOC World Bird List Version 4.2”. doi:10.14344/IOC.ML.4.2. 2014年7月29日閲覧。

- ^ 山岸 (2002)、36頁

- ^ a b ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、30頁

- ^ a b Borenstein, Seth (2014年7月31日). “Study traces dinosaur evolution into early birds”. AP News 2015年3月8日閲覧。

- ^ a b Lee, Michael S. Y.; Cau, Andrea; Naish, Darren; Dyke, Gareth J. (1 August 2014). “Sustained miniaturization and anatomical innovation in the dinosaurian ancestors of birds”. Science 345 (6196): 562–566. doi:10.1126/science.1252243 2014年8月2日閲覧。.

- ^ 『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)、1-2頁

- ^ 『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)、805-806頁

- ^ 『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)、330頁、798-799頁

- ^ a b ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、626頁

- ^ a b 山階鳥研 (2006)、16頁

- ^ a b Livezey, Bradley C.; Zusi, RL (2007-01). “Higher-order phylogeny of modern birds (Theropoda, Aves: Neornithes) based on comparative anatomy. II. Analysis and discussion”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 149 (1): 1–95. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00293.x. PMC 2517308. PMID 18784798.

- ^ 山岸 (2002)、4-7頁

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2002). “Looking for the True Bird Ancestor”. Dinosaurs of the Air: The Evolution and Loss of Flight in Dinosaurs and Birds. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 171–224. ISBN 0-8018-6763-0

- ^ Xing Xu, Hailu You, Kai Du and Fenglu Han (28 July 2011). “An Archaeopteryx-like theropod from China and the origin of Avialae”. Nature 475 (7357): 465–470. doi:10.1038/nature10288. PMID 21796204.

- ^ 土谷健 著、小林快次監修 編『そして恐竜は鳥になった』誠文堂新光社、2013年、81-82頁。ISBN 978-4-416-11365-3。

- ^ Turner, Alan H.; Pol, D; Clarke, JA; Erickson, GM; Norell, MA (2007-09-07). “A Basal Dromaeosaurid and Size Evolution Preceding Avian Flight” (PDF). Science 317 (5843): 1378–1381. doi:10.1126/science.1144066. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17823350 2014年6月22日閲覧。.

- ^ Xu, Xing; Zhou, Zhonghe; Wang, Xiaolin; Kuang, Xuewen; Zhang, Fucheng; Du, Xiangke (January 2003). “Four-winged dinosaurs from China”. Nature 421 (6921): 335–340. doi:10.1038/nature01342. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 12540892.

- ^ Heilmann, Gerhard (1927). The Origin of Birds. New York: Dover Publications.

- ^ Rasskin-Gutman, Diego; Buscalioni, Angela D. (March 2001). “Theoretical morphology of the Archosaur (Reptilia: Diapsida) pelvic girdle”. Paleobiology 27 (1): 59–78. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2001)027<0059:TMOTAR>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0094-8373.

- ^ Feduccia, Alan; Lingham-Soliar, T; Hinchliffe, JR (November 2005). “Do feathered dinosaurs exist? Testing the hypothesis on neontological and paleontological evidence”. Journal of Morphology 266 (2): 125–66. doi:10.1002/jmor.10382. ISSN 0362-2525. PMID 16217748.

- ^ Prum, Richard O. (April 2003). “Are Current Critiques Of The Theropod Origin Of Birds Science? Rebuttal To Feduccia 2002”. The Auk 120 (2): 550–61. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2003)120[0550:ACCOTT]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0004-8038. JSTOR 4090212.

- ^ Padian, Kevin; L.M. Chiappe Chiappe LM (1997). “Bird Origins”. In Philip J. Currie and Kevin Padian (eds.). Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 41–96. ISBN 0-12-226810-5

- ^ 『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)、185頁

- ^ 『恐竜学入門』 (2015)、217-220頁

- ^ Norell, Mark; Mick Ellison (2005). Unearthing the Dragon: The Great Feathered Dinosaur Discovery. New York: Pi Press. ISBN 0-13-186266-9

- ^ a b c d e Chiappe, Luis M. (2007). Glorified Dinosaurs: The Origin and Early Evolution of Birds. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-86840-413-4

- ^ a b c d e 冨田ほか 2020.

- ^ 『恐竜学入門』 (2015)、208-209頁

- ^ Gauthier, Jacques (1986). “Saurischian Monophyly and the origin of birds”. In Kevin Padian. The Origin of Birds and the Evolution of Flight. Memoirs of the California Academy of Science 8. San Francisco, CA: Published by California Academy of Sciences. pp. 1–55. ISBN 0-940228-14-9

- ^ 『恐竜学入門』 (2015)、208頁

- ^ 『恐竜学入門』 (2015)、207-209頁

- ^ Mayr, G.; Phol, B.; Hartman, S.; Peters, D.S. (2007). “The tenth skeletal specimen of Archaeopteryx”. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 149: 97–116. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00245.x.

- ^ “On the Origin of Birds”. TheScientist (2011年7月27日). 2014年6月21日閲覧。

- ^ Clarke, Julia A. (September 2004). “Morphology, Phylogenetic Taxonomy, and Systematics of Ichthyornis and Apatornis (Avialae: Ornithurae)”. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 286: 1–179. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2004)286<0001:MPTASO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0003-0090 2014年6月22日閲覧。.

- ^ パーカー 2020, p. 385.

- ^ Ritchison, Gary. “Bird biogeography”. 2014年6月22日閲覧。

- ^ Harshman, John; et al. (2008). “Phylogenomic evidence for multiple losses of flight in ratite birds”. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105 2014年6月28日閲覧。.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u パーカー 2020, p. 371.

- ^ Clarke, Julia A.; Tambussi, CP; Noriega, JI; Erickson, GM; Ketcham, RA (January 2005). “Definitive fossil evidence for the extant avian radiation in the Cretaceous” (PDF). Nature 433 (7023): 305–308. doi:10.1038/nature03150. PMID 15662422 2014年6月23日閲覧。. Nature.com - 概要

- ^ a b c d Ericson, Per G.P.; Anderson, CL; Britton, T; Elzanowski, A; Johansson, US; Källersjö, M; Ohlson, JI; Parsons, TJ et al. (December 2006), “Diversification of Neoaves: Integration of molecular sequence data and fossils” (PDF), Biology Letters 2 (4): 543–547, doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0523, ISSN 1744-9561, PMC 1834003, PMID 17148284

- ^ Brown, Joseph W.; Payne, RB; Mindell, DP (June 2007), “Nuclear DNA does not reconcile 'rocks' and 'clocks' in Neoaves: a comment on Ericson et al.”, Biology Letters 3 (3): 257–259, doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0611, ISSN 1744-9561, PMC 2464679, PMID 17389215

- ^ Clements, James F. (2007). The Clements Checklist of Birds of the World (6th ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4501-9

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、77頁

- ^ del Hoyo, Josep; Andy Elliott and Jordi Sargatal (1992). Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona: w:Lynx Edicions. ISBN 84-87334-10-5

- ^ (ラテン語) Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 824

- ^ Sibley, Charles; Jon Edward Ahlquist (1990). Phylogeny and classification of birds. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04085-7

- ^ Mayr, Ernst; Short, Lester L. (1970). Species Taxa of North American Birds: A Contribution to Comparative Systematics. Publications of the Nuttall Ornithological Club, no. 9. Cambridge, Mass.: Nuttall Ornithological Club. OCLC 517185

- ^ Tolweb.org, "Neoaves". Tree of Life Project

- ^ a b c Hackett, S.J.; et al. (2008-07-12). “A Phylogenomic Study of Birds Reveals Their Evolutionary History” (PDF). Science 320 (5884): 1763-1768 2014年6月25日閲覧。.

- ^ a b c d e Mayr, Gerald (2011). “Metaves, Mirandornithes, Strisores and other novelties – a critical review of the higher-level phylogeny of neornithine birds” (PDF). J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 49 (1): 58–76. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2010.00586.x 2014年6月25日閲覧。.

- ^ a b 山崎, 剛史; 亀谷, 辰朗 (2019). “鳥類の目と科の新しい和名(1) 非スズメ目・イワサザイ類・亜鳴禽類”. 山階鳥類学雑誌 50 (2): 141–151. doi:10.3312/jyio.50.141.

- ^ Sangster, G. (2005), “A name for the flamingo-grebe clade”, Ibis 147: 612–615, doi:10.1111/j.1474-919x.2005.00432.x

- ^ a b c Suh, Alexander; et al. (2011). “Mesozoic retroposons reveal parrots as the closest living relatives of passerine birds”. Nature 2 (8). doi:10.1038/ncomms1448 2014年6月25日閲覧。.

- ^ Braun, E. L.; Kimball, R. T. (2021). “Data types and the phylogeny of Neoaves”. Birds 2 (1): 1–22. doi:10.3390/birds2010001.

- ^ Boyd, John (2007年). “NEORNITHES: 46 Orders”. John Boyd's website. 2017年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ パーカー 2020, p. 398.

- ^ パーカー 2020, p. 370.

- ^ Newton, Ian (2003). The Speciation and Biogeography of Birds. Amsterdam: Academic Press. p. 463. ISBN 0-12-517375-X

- ^ Brooke, Michael (2004). Albatrosses And Petrels Across The World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850125-0

- ^ Weir, Jason T.; Schluter, D (March 2007). “The Latitudinal Gradient in Recent Speciation and Extinction Rates of Birds and Mammals”. Science 315 (5818): 1574–76. doi:10.1126/science.1135590. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17363673.

- ^ a b Schreiber, Elizabeth Anne; Joanna Burger (2001). Biology of Marine Birds. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-9882-7

- ^ Sato, Katsufumi; N; K; N; W; C; B; H et al. (1 May 2002). “Buoyancy and maximal diving depth in penguins: do they control inhaling air volume?”. Journal of Experimental Biology 205 (9): 1189–1197. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 11948196 2014年6月28日閲覧。.

- ^ 佐藤克文『巨大翼竜は飛べたのか - スケールと行動の動物学』平凡社〈平凡社新書〉、2011年、30-31,59頁。ISBN 978-4-582-85568-5。

- ^ Hill, David; Peter Robertson (1988). The Pheasant: Ecology, Management, and Conservation. Oxford: BSP Professional. ISBN 0-632-02011-3

- ^ Spreyer, Mark F.; Enrique H. Bucher (1998年). “Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus)”. The Birds of North America. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bna.322. 2014年6月28日閲覧。

- ^ Arendt, Wayne J. (1988-01-01). “Range Expansion of the Cattle Egret, (Bubulcus ibis) in the Greater Caribbean Basin”. Colonial Waterbirds 11 (2): 252–62. doi:10.2307/1521007. ISSN 07386028. JSTOR 1521007.

- ^ Bierregaard, R.O. (1994). “Yellow-headed Caracara”. In Josep del Hoyo, Andrew Elliott and Jordi Sargatal (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 2; New World Vultures to Guineafowl. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 84-87334-15-6

- ^ Juniper, Tony; Mike Parr (1998). Parrots: A Guide to the Parrots of the World. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-6933-0

- ^ 松岡廣繁・安部きみ子 編『鳥の骨探』NTS〈BONE DESIGN SERIES〉、2009年、18-19頁。ISBN 978-4-86043-276-8。

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul R.; David S. Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye (1988年). “Adaptations for Flight”. Birds of Stanford. Stanford University. 2014年6月28日閲覧。 The Birder's Handbook (Paul Ehrlich, David Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye. 1988. Simon and Schuster, New York.) に基づく

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、51頁

- ^ “The Avian Skeleton”. paulnoll.com 2014年6月29日閲覧。

- ^ a b ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、28頁

- ^ “Skeleton”. Fernbank Science Center's Ornithology Web. 2014年6月29日閲覧。

- ^ 『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)、496頁

- ^ 和田勝「食べて消化する」『Birder』第14巻第11号、文一総合出版、2000年11月、8-9頁。

- ^ Gionfriddo, James P.; Best (1 February 1995). “Grit Use by House Sparrows: Effects of Diet and Grit Size” (PDF). Condor 97 (1): 57–67. doi:10.2307/1368983. ISSN 00105422 2014年6月29日閲覧。.

- ^ a b c Attenborough, David (1998). The Life of Birds. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01633-X

- ^ a b Battley, Phil F.; Piersma, T; Dietz, MW; Tang, S; Dekinga, A; Hulsman, K (January 2000). “Empirical evidence for differential organ reductions during trans-oceanic bird flight”. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 267 (1439): 191–5. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.0986. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1690512. PMID 10687826. (Erratum in Proceedings of the Royal Society B 267(1461):2567.)

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul R.; David S. Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye (1988年). “Drinking”. Birds of Stanford. Standford University. 2014年6月29日閲覧。

- ^ Tsahar, Ella; Martínez Del Rio, C; Izhaki, I; Arad, Z (March 2005). “Can birds be ammonotelic? Nitrogen balance and excretion in two frugivores”. Journal of Experimental Biology 208 (6): 1025–34. doi:10.1242/jeb.01495. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 15767304.

- ^ Skadhauge, E; Erlwanger, KH; Ruziwa, SD; Dantzer, V; Elbrønd, VS; Chamunorwa, JP (2003). “Does the ostrich (Struthio camelus) coprodeum have the electrophysiological properties and microstructure of other birds?”. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Part A, Molecular & integrative physiology 134 (4): 749–755. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(03)00006-0. PMID 12814783.

- ^ Preest, Marion R.; Beuchat, Carol A. (April 1997). “Ammonia excretion by hummingbirds”. Nature 386 (6625): 561–62. doi:10.1038/386561a0.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gill, Frank (1995). Ornithology. New York: WH Freeman and Co. ISBN 0-7167-2415-4

- ^ Mora, J.; Martuscelli, J; Ortiz Pineda, J; Soberon, G (July 1965). “The Regulation of Urea-Biosynthesis Enzymes in Vertebrates” (PDF). Biochemical Journal 96: 28–35. ISSN 0264-6021. PMC 1206904. PMID 14343146.

- ^ Packard, Gary C. (1966). “The Influence of Ambient Temperature and Aridity on Modes of Reproduction and Excretion of Amniote Vertebrates”. The American Naturalist 100 (916): 667–82. doi:10.1086/282459. JSTOR 2459303.

- ^ Balgooyen, Thomas G. (1 October 1971). “Pellet Regurgitation by Captive Sparrow Hawks (Falco sparverius)” (PDF). Condor 73 (3): 382–85. doi:10.2307/1365774. ISSN 00105422. JSTOR 1365774 2014年6月29日閲覧。.

- ^ “鳥の体あれこれ”. www.anat.hiroshima-u.ac.jp. 広島大学. 2023年10月26日閲覧。

- ^ 運隆, 本間 (1970). “鳥卵形成の生理化学”. 化学と生物 8 (8): 461–467. doi:10.1271/kagakutoseibutsu1962.8.461.

- ^ Maina, John N. (November 2006). “Development, structure, and function of a novel respiratory organ, the lung-air sac system of birds: to go where no other vertebrate has gone”. Biological Reviews 81 (4): 545–79. doi:10.1017/S1464793106007111. ISSN 1464-7931. PMID 17038201.

- ^ 和田勝「さえずるってどうゆうこと」『Birder』第15巻第10号、文一総合出版、2001年10月、64-65頁。

- ^ a b Suthers, Roderick A.; Sue Anne Zollinger (2004). “Producing song: the vocal apparatus”. In H. Philip Zeigler and Peter Marler (eds.). Behavioral Neurobiology of Birdsong. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1016. New York: New York Academy of Sciences. pp. 109–129. doi:10.1196/annals.1298.041. ISBN 1-57331-473-0 PMID 15313772

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、162頁

- ^ 和田勝「血の巡りをよく」『Birder』第14巻第12号、文一総合出版、2000年12月、8-9頁。

- ^ 和田勝「赤い血が流れて」『Birder』第15巻第1号、文一総合出版、2001年1月、66-68頁。

- ^ Scott, Robert B. (March 1966). “Comparative hematology: The phylogeny of the erythrocyte”. Annals of Hematology 12 (6): 340–51. doi:10.1007/BF01632827. ISSN 0006-5242. PMID 5325853.

- ^ 芝田 猛、渡辺 誠喜、ウズラの成長に伴う血糖値の変化と血糖成分、日本畜産学会報 Vol. 52 (1981) No.12、P 869-873、https://doi.org/10.2508/chikusan.52.869

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、208-209頁

- ^ Sales, James (2005). “The endangered kiwi: a review” (PDF). Folia Zoologica 54 (1–2): 1–20 2014年7月1日閲覧。.

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul R.; David S. Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye (1988年). “The Avian Sense of Smell”. Birds of Stanford. Standford University. 2014年7月1日閲覧。

- ^ Lequette, Benoit; Verheyden; Jouventin (1 August 1989). “Olfaction in Subantarctic seabirds: Its phylogenetic and ecological significance” (PDF). The Condor 91 (3): 732–35. doi:10.2307/1368131. ISSN 00105422.

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、195頁

- ^ Wilkie, Susan E.; Vissers, PM; Das, D; Degrip, WJ; Bowmaker, JK; Hunt, DM (February 1998). “The molecular basis for UV vision in birds: spectral characteristics, cDNA sequence and retinal localization of the UV-sensitive visual pigment of the budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus)”. Biochemical Journal 330: 541–47. ISSN 0264-6021. PMC 1219171. PMID 9461554.

- ^ Andersson, S.; J. Ornborg and M. Andersson (1998). “Ultraviolet sexual dimorphism and assortative mating in blue tits”. Proceeding of the Royal Society B 265 (1395): 445–50. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0315.

- ^ Viitala, Jussi; Korplmäki, Erkki; Palokangas, Pälvl; Koivula, Minna (1995). “Attraction of kestrels to vole scent marks visible in ultraviolet light”. Nature 373 (6513): 425–27. doi:10.1038/373425a0.

- ^ Williams, David L.; Flach, E (March 2003). “Symblepharon with aberrant protrusion of the nictitating membrane in the snowy owl (Nyctea scandiaca)”. Veterinary Ophthalmology 6 (1): 11–13. doi:10.1046/j.1463-5224.2003.00250.x. ISSN 1463-5216. PMID 12641836.

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、194-195頁

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、197-198頁

- ^ White, Craig R.; Day, N; Butler, PJ; Martin, GR; Bennett, Peter (July 2007). Bennett, Peter. ed. “Vision and Foraging in Cormorants: More like Herons than Hawks?”. PLoS ONE 2 (7): e639. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000639. PMC 1919429. PMID 17653266.

- ^ Martin, Graham R.; Katzir, G (1999). “Visual fields in Short-toed Eagles, Circaetus gallicus (Accipitridae), and the function of binocularity in birds”. Brain, Behaviour and Evolution 53 (2): 55–66. doi:10.1159/000006582. ISSN 0006-8977. PMID 9933782.

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、200頁

- ^ Saito, Nozomu (1978). “Physiology and anatomy of avian ear”. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 64 (S1): S3. doi:10.1121/1.2004193.

- ^ Warham, John (1 May 1977). “The Incidence, Function and ecological significance of petrel stomach oils” (PDF). Proceedings of the New Zealand Ecological Society 24 (3): 84–93. doi:10.2307/1365556. ISSN 00105422. JSTOR 1365556 2014年7月4日閲覧。.

- ^ 山階鳥研 (2006)、174-177頁

- ^ Dumbacher, J.P.; Beehler, BM; Spande, TF; Garraffo, HM; Daly, JW (October 1992). “Homobatrachotoxin in the genus Pitohui: chemical defense in birds?”. Science 258 (5083): 799–801. doi:10.1126/science.1439786. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 1439786.

- ^ 山階鳥研 (2006)、175頁

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、401-402頁

- ^ Göth, Anne (2007). “Incubation temperatures and sex ratios in Australian brush-turkey (Alectura lathami) mounds”. Austral Ecology 32 (4): 278–85. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2007.01709.x.

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、100頁

- ^ a b c d e 茂田良光「鳥類の羽毛と換羽」『BIRDER』第11巻第8号、文一総合出版、1997年8月、27-33頁。

- ^ Belthoff, James R.; Dufty,; Gauthreaux, (1 August 1994). “Plumage Variation, Plasma Steroids and Social Dominance in Male House Finches”. The Condor 96 (3): 614–25. doi:10.2307/1369464. ISSN 00105422.

- ^ Guthrie, R. Dale. “How We Use and Show Our Social Organs”. Body Hot Spots: The Anatomy of Human Social Organs and Behavior. 2007年6月21日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2014年7月5日閲覧。

- ^ Humphrey, Philip S. (1 June 1959). “An approach to the study of molts and plumages” (PDF). The Auk 76 (2): 1–31. doi:10.2307/3677029. ISSN 09088857. JSTOR 3677029 2014年7月5日閲覧。.

- ^ a b ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、129頁

- ^ Payne, Robert B. “Birds of the World, Biology 532”. Bird Division, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. 2007年10月20日閲覧。

- ^ a b c Pettingill Jr. OS (1970). Ornithology in Laboratory and Field. Burgess Publishing Co. ISBN 0808716093

- ^ a b 山階鳥研 (2004)、65頁

- ^ de Beer SJ, Lockwood GM, Raijmakers JHFS, Raijmakers JMH, Scott WA, Oschadleus HD, Underhill (2001年). “SAFRING Bird Ringing Manual” (PDF). p. 60. 2014年7月5日閲覧。

- ^ Ernst, Mayr; Margaret, Mayr (1954). “The tail molt of small owls” (PDF). The Auk 71 (2): 172–178 2014年7月5日閲覧。.

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、450-451頁

- ^ Turner, J. Scott (July 1997). “On the thermal capacity of a bird's egg warmed by a brood patch”. Physiological Zoology 70 (4): 470–80. doi:10.1086/515854. ISSN 0031-935X. PMID 9237308.

- ^ Walther, Bruno A. (2005). “Elaborate ornaments are costly to maintain: evidence for high maintenance handicaps”. Behavioural Ecology 16 (1): 89–95. doi:10.1093/beheco/arh135.

- ^ Shawkey, Matthew D.; Pillai, Shreekumar R.; Hill, Geoffrey E. (2003). “Chemical warfare? Effects of uropygial oil on feather-degrading bacteria”. Journal of Avian Biology 34 (4): 345–49. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2003.03193.x.

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul R. (1986). “The Adaptive Significance of Anting” (PDF). The Auk 103 (4): 835.

- ^ Stout, Sam D.; Agarwal, Sabrina C.; Stout, Samuel D. (2003). Bone loss and osteoporosis: an anthropological perspective. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. ISBN 0-306-47767-X

- ^ Lucas, Alfred M. (1972). Avian Anatomy—integument. East Lansing, Michigan, US: USDA Avian Anatomy Project, Michigan State University. pp. 67, 344, 394–601

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、131-138頁

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、27頁、147頁

- ^ 『鳥類学辞典』 (2004)、698頁

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、149-151頁

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、146-147頁

- ^ Roots, Clive (2006). Flightless Birds. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33545-7

- ^ McNab, Brian K. (October 1994). “Energy Conservation and the Evolution of Flightlessness in Birds”. The American Naturalist 144 (4): 628–42. doi:10.1086/285697. JSTOR 2462941.

- ^ Kovacs, Christopher E.; Meyers, RA (May 2000). “Anatomy and histochemistry of flight muscles in a wing-propelled diving bird, the Atlantic Puffin, Fratercula arctica”. Journal of Morphology 244 (2): 109–25. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(200005)244:2<109::AID-JMOR2>3.0.CO;2-0. PMID 10761049.

- ^ Robert, Michel (January 1989). “Conditions and significance of night feeding in shorebirds and other water birds in a tropical lagoon” (PDF). The Auk 106 (1): 94–101 2014年7月6日閲覧。.

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、32頁

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、26-27頁、177-178頁

- ^ N Reid (2006年). “Birds on New England wool properties - A woolgrower guide” (PDF). Land, Water & Wool Northern Tablelands Property Fact Sheet. Australian Government - Land and Water Australia. 2014年7月21日閲覧。

- ^ Paton, D. C.; Baker, . (1 April 1989). “Bills and tongues of nectar-feeding birds: A review of morphology, function, and performance, with intercontinental comparisons”. Australian Journal of Ecology 14 (4): 473–506. doi:10.2307/1942194. ISSN 00129615. JSTOR 1942194.

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、32-34頁

- ^ Baker, Myron Charles; Baker, . (1 April 1973). “Niche Relationships Among Six Species of Shorebirds on Their Wintering and Breeding Ranges”. Ecological Monographs 43 (2): 193–212. doi:10.2307/1942194. ISSN 00129615. JSTOR 1942194.

- ^ Cherel, Yves; Bocher, P; De Broyer, C; Hobson, KA (2002). “Food and feeding ecology of the sympatric thin-billed Pachyptila belcheri and Antarctic P. desolata prions at Iles Kerguelen, Southern Indian Ocean”. Marine Ecology Progress Series 228: 263–281. doi:10.3354/meps228263.

- ^ Jenkin, Penelope M. (1957). “The Filter-Feeding and Food of Flamingoes (Phoenicopteri)”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 240 (674): 401–493. doi:10.1098/rstb.1957.0004. JSTOR 92549.

- ^ Miyazaki, Masamine; Kuroki, M.; Niizuma, Y.; Watanuki, Y. (1 July 1996). “Vegetation cover, kleptoparasitism by diurnal gulls and timing of arrival of nocturnal Rhinoceros Auklets” (PDF). The Auk 113 (3): 698–702. doi:10.2307/3677021. ISSN 09088857. JSTOR 3677021 2014年7月6日閲覧。.

- ^ Bélisle, Marc; Giroux (1 August 1995). “Predation and kleptoparasitism by migrating Parasitic Jaegers” (PDF). The Condor 97 (3): 771–781. doi:10.2307/1369185. ISSN 00105422 2014年7月6日閲覧。.

- ^ Vickery, J. A.; Brooke, . (1 May 1994). “The Kleptoparasitic Interactions between Great Frigatebirds and Masked Boobies on Henderson Island, South Pacific” (PDF). The Condor 96 (2): 331–40. doi:10.2307/1369318. ISSN 00105422. JSTOR 1369318 2014年7月6日閲覧。.

- ^ Hiraldo, F.C.; Blanco, J. C.; Bustamante, J. (1991). “Unspecialized exploitation of small carcasses by birds”. Bird Studies 38 (3): 200–07. doi:10.1080/00063659109477089.

- ^ Dinosaur lactation? Paul L. Else Journal of Experimental Biology 2013 216: 347-351; doi: 10.1242/jeb.065383 https://jeb.biologists.org/content/216/3/347.short

- ^ Engel, Sophia Barbara (2005). Racing the wind: Water economy and energy expenditure in avian endurance flight. University of Groningen. ISBN 90-367-2378-7 2014年7月6日閲覧。

- ^ Tieleman, B.I.; Williams, J.B (January 1999). “The Role of Hyperthermia in the Water Economy of Desert Birds” (PDF). Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 72 (1): 87–100. doi:10.1086/316640. ISSN 1522-2152. PMID 9882607 2014年7月6日閲覧。.

- ^ Schmidt-Nielsen, Knut (1 May 1960). “The Salt-Secreting Gland of Marine Birds”. Circulation 21 (5): 955–967 2014年7月6日閲覧。.

- ^ Hallager, Sara L. (1994). “Drinking methods in two species of bustards” (PDF). Wilson Bull. 106 (4): 763–764 2014年7月6日閲覧。.

- ^ MacLean, Gordon L. (1 June 1983). “Water Transport by Sandgrouse”. BioScience 33 (6): 365–369. doi:10.2307/1309104. ISSN 00063568. JSTOR 1309104.

- ^ Eraud C; Dorie A; Jacquet A & Faivre B (2008). “The crop milk: a potential new route for carotenoid-mediated parental effects”. Journal of Avian Biology 39 (2): 247–251. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2008.04053.x.

- ^ Klaassen, Marc (1 January 1996). “Metabolic constraints on long-distance migration in birds”. Journal of Experimental Biology 199 (1): 57–64. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 9317335 2014年7月7日閲覧。.

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、291-293頁

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、285頁

- ^ 樋口 (2016)、22頁、112-113頁

- ^ “The Bar-tailed Godwit undertakes one of the avian world's most extraordinary migratory journeys”. BirdLife International (2010年). 2014年7月7日閲覧。

- ^ 樋口 (2016)、113-114頁

- ^ Shaffer, Scott A.; Tremblay, Y; Weimerskirch, H; Scott, D; Thompson, DR; Sagar, PM; Moller, H; Taylor, GA et al. (August 2006). “Migratory shearwaters integrate oceanic resources across the Pacific Ocean in an endless summer”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103 (34): 12799–12802. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603715103. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1568927. PMID 16908846 2014年7月7日閲覧。.

- ^ Croxall, John P.; Silk, JR; Phillips, RA; Afanasyev, V; Briggs, DR (January 2005). “Global Circumnavigations: Tracking year-round ranges of nonbreeding Albatrosses”. Science 307 (5707): 249–50. doi:10.1126/science.1106042. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15653503.

- ^ Wilson, W. Herbert, Jr. (1999). “Bird feeding and irruptions of northern finches:are migrations short stopped?” (PDF). North America Bird Bander 24 (4): 113–21 2014年7月7日閲覧。.

- ^ Nilsson, Anna L. K.; Alerstam, Thomas; Nilsson, Jan-Åke (2006). “Do partial and regular migrants differ in their responses to weather?”. The Auk 123 (2): 537–547. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2006)123[537:DPARMD]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0004-8038.

- ^ Chan, Ken (2001). “Partial migration in Australian landbirds: a review”. Emu 101 (4): 281–92. doi:10.1071/MU00034 2014年7月7日閲覧。.

- ^ Rabenold, Kerry N. (1985). “Variation in Altitudinal Migration, Winter Segregation, and Site Tenacity in two subspecies of Dark-eyed Juncos in the southern Appalachians” (PDF). The Auk 102 (4): 805–19 2014年7月7日閲覧。.

- ^ Collar, Nigel J. (1997). “Family Psittacidae (Parrots)”. In Josep del Hoyo, Andrew Elliott and Jordi Sargatal (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World, Volume 4: Sandgrouse to Cuckoos. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 84-87334-22-9

- ^ Matthews, G. V. T. (1 September 1953). “Navigation in the Manx Shearwater”. Journal of Experimental Biology 30 (2): 370–396.

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、300頁

- ^ Mouritsen, Henrik; L (15 November 2001). “Migrating songbirds tested in computer-controlled Emlen funnels use stellar cues for a time-independent compass”. Journal of Experimental Biology 204 (8): 3855–3865. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 11807103 2014年7月7日閲覧。.

- ^ Deutschlander, Mark E.; P; B (15 April 1999). “The case for light-dependent magnetic orientation in animals”. Journal of Experimental Biology 202 (8): 891–908. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 10085262 2014年7月7日閲覧。.

- ^ Möller, Anders Pape (1988). “Badge size in the house sparrow Passer domesticus”. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 22 (5): 373–78.

- ^ Thomas, Betsy Trent; Strahl, Stuart D. (1 August 1990). “Nesting Behavior of Sunbitterns (Eurypyga helias) in Venezuela”. The Condor 92 (3): 576–81. doi:10.2307/1368675. ISSN 00105422 2014年7月7日閲覧。.

- ^ Pickering, S. P. C. (2001). “Courtship behaviour of the Wandering Albatross Diomedea exulans at Bird Island, South Georgia”. Marine Ornithology 29 (1): 29–37 2014年7月7日閲覧。.

- ^ Pruett-Jones, S. G.; Pruett-Jones (1 May 1990). “Sexual Selection Through Female Choice in Lawes' Parotia, A Lek-Mating Bird of Paradise”. Evolution 44 (3): 486–501. doi:10.2307/2409431. ISSN 00143820.

- ^ a b ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、228頁

- ^ Genevois, F.; Bretagnolle, V. (1994). “Male Blue Petrels reveal their body mass when calling”. Ethology Ecology and Evolution 6 (3): 377–83. doi:10.1080/08927014.1994.9522988.

- ^ Jouventin, Pierre; Aubin, T; Lengagne, T (June 1999). “Finding a parent in a king penguin colony: the acoustic system of individual recognition”. Animal Behaviour 57 (6): 1175–83. doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1086. ISSN 0003-3472. PMID 10373249.

- ^ Templeton, Christopher N.; Greene, E; Davis, K (June 2005). “Allometry of Alarm Calls: Black-Capped Chickadees Encode Information About Predator Size”. Science 308 (5730): 1934–37. doi:10.1126/science.1108841. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15976305.

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、228-230頁

- ^ 高野伸二 編『カラー写真による 日本産鳥類図鑑』東海大学出版会、1981年、281頁。

- ^ a b Miskelly, C. M. (July 1987). “The identity of the hakawai” (PDF). Notornis 34 (2): 95–116 2014年7月7日閲覧。.

- ^ 茂田良光「ジシギ類ってどんな鳥」『Birder』第14巻第5号、文一総合出版、2000年5月、26-31頁。

- ^ Murphy, Stephen; Legge, Sarah; Heinsohn, Robert (2003). “The breeding biology of palm cockatoos (Probosciger aterrimus): a case of a slow life history”. w:Journal of Zoology 261 (4): 327–39. doi:10.1017/S0952836903004175.

- ^ a b Sekercioglu, Cagan Hakki (2006). “Foreword”. In Josep del Hoyo, Andrew Elliott and David Christie (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World, Volume 11: Old World Flycatchers to Old World Warblers. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. p. 48. ISBN 84-96553-06-X

- ^ Terborgh, John (2005). “Mixed flocks and polyspecific associations: Costs and benefits of mixed groups to birds and monkeys”. American Journal of Primatology 21 (2): 87–100. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350210203.

- ^ Hutto, Richard L. (1 January 1988). “Foraging Behavior Patterns Suggest a Possible Cost Associated with Participation in Mixed-Species Bird Flocks”. Oikos 51 (1): 79–83. doi:10.2307/3565809. ISSN 00301299. JSTOR 3565809.

- ^ Au, David W. K.; Pitman (1 August 1986). “Seabird interactions with Dolphins and Tuna in the Eastern Tropical Pacific” (PDF). The Condor 88 (3): 304–17. doi:10.2307/1368877. ISSN 00105422.

- ^ Anne, O.; Rasa, E. (June 1983). “Dwarf mongoose and hornbill mutualism in the Taru desert, Kenya”. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 12 (3): 181–90. doi:10.1007/BF00290770.

- ^ Gauthier-Clerc, Michael; Tamisier, Alain; Cézilly, Frank (May 2000). “Sleep-Vigilance Trade-off in Gadwall during the Winter Period” (PDF). The Condor 102 (2): 307–13. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2000)102[0307:SVTOIG]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0010-5422 2014年7月8日閲覧。.

- ^ 樋口 (2016)、21-22頁

- ^ Bäckman, Johan; A (1 April 2002). “Harmonic oscillatory orientation relative to the wind in nocturnal roosting flights of the swift Apus apus”. The Journal of Experimental Biology 205 (7): 905–910. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 11916987 2014年7月8日閲覧。.

- ^ Rattenborg, Niels C. (September 2006). “Do birds sleep in flight?”. Die Naturwissenschaften 93 (9): 413–425. doi:10.1007/s00114-006-0120-3. ISSN 0028-1042. PMID 16688436.

- ^ Milius, S. (6 February 1999). “Half-asleep birds choose which half dozes”. Science News Online 155 (6): 86. doi:10.2307/4011301. ISSN 00368423. JSTOR 4011301. オリジナルの2012-05-29時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Beauchamp, Guy (1999). “The evolution of communal roosting in birds: origin and secondary losses”. Behavioural Ecology 10 (6): 675–87. doi:10.1093/beheco/10.6.675 2014年7月8日閲覧。.

- ^ Buttemer, William A. (1985). “Energy relations of winter roost-site utilization by American goldfinches (Carduelis tristis)”. w:Oecologia 68 (1): 126–32. doi:10.1007/BF00379484 2014年7月8日閲覧。.

- ^ Buckley, F. G.; Buckley (1 January 1968). “Upside-down Resting by Young Green-Rumped Parrotlets (Forpus passerinus)” (PDF). The Condor 70 (1): 89. doi:10.2307/1366517. ISSN 00105422 2014年7月11日閲覧。.

- ^ Carpenter, F. Lynn (February 1974). “Torpor in an Andean Hummingbird: Its Ecological Significance”. Science 183 (4124): 545–547. doi:10.1126/science.183.4124.545. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17773043.

- ^ McKechnie, Andrew E.; Ashdown, Robert A. M.; Christian, Murray B.; Brigham, R. Mark (2007). “Torpor in an African caprimulgid, the freckled nightjar Caprimulgus tristigma”. Journal of Avian Biology 38 (3): 261–66. doi:10.1111/j.2007.0908-8857.04116.x.

- ^ Frith, C.B (1981). “Displays of Count Raggi's Bird-of-Paradise Paradisaea raggiana and congeneric species”. Emu 81 (4): 193–201. doi:10.1071/MU9810193 2014年7月12日閲覧。.

- ^ Freed, Leonard A. (1987). “The Long-Term Pair Bond of Tropical House Wrens: Advantage or Constraint?”. The American Naturalist 130 (4): 507–25. doi:10.1086/284728.

- ^ Gowaty, Patricia A. (1983). “Male Parental Care and Apparent Monogamy among Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis)”. The American Naturalist 121 (2): 149–60. doi:10.1086/284047.

- ^ Westneat, David F.; Stewart, Ian R.K. (2003). “Extra-pair paternity in birds: Causes, correlates, and conflict”. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 34: 365–96. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132439.

- ^ Sheldon, B (1994). “Male Phenotype, Fertility, and the Pursuit of Extra-Pair Copulations by Female Birds”. Proceedings: Biological Sciences 257 (1348): 25–30. doi:10.1098/rspb.1994.0089.

- ^ Wei, G; Zuo-Hua, Yin; Fu-Min, Lei (2005). “Copulations and mate guarding of the Chinese Egret”. Waterbirds 28 (4): 527–30. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2005)28[527:CAMGOT]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1524-4695.

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、368頁

- ^ 山岸 (2002)、111頁、118-119頁

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、370-372頁

- ^ 山岸 (2002)、109-112頁、121-122頁

- ^ Short, Lester L. (1993). Birds of the World and their Behavior. New York: Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 0-8050-1952-9

- ^ Burton, R (1985). Bird Behavior. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0-394-53957-5

- ^ Schamel, D; Tracy, Diane M.; Lank, David B.; Westneat, David F. (2004). “Mate guarding, copulation strategies and paternity in the sex-role reversed, socially polyandrous red-necked phalarope Phalaropus lobatus”. Behaviour Ecology and Sociobiology 57 (2): 110–118. doi:10.1007/s00265-004-0825-2 2014年7月12日閲覧。.

- ^ Bagemihl, Bruce (1999). Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity. New York: St. Martin's. p. 479-655 100種を詳細に記載。

- ^ Kokko, H; Harris, M; Wanless, S (2004). “Competition for breeding sites and site-dependent population regulation in a highly colonial seabird, the common guillemot Uria aalge"”. Journal of Animal Ecology 73 (2): 367–76. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8790.2004.00813.x.

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、416-423頁

- ^ Booker, L; Booker, M (1991). “Why Are Cuckoos Host Specific?”. Oikos 57 (3): 301–09. doi:10.2307/3565958. JSTOR 3565958.

- ^ 小海途銀治郎、和田岳『日本 鳥の巣図鑑 - 小海途銀次郎コレクション』東海大学出版会〈大阪市立自然史博物館叢書 5〉、2011年、331-332頁。ISBN 978-4-486-01911-4。

- ^ a b Hansell M (2000). Bird Nests and Construction Behaviour. University of Cambridge Press ISBN 0-521-46038-7

- ^ Lafuma, L; Lambrechts, M; Raymond, M (2001). “Aromatic plants in bird nests as a protection against blood-sucking flying insects?”. Behavioural Processes 56 (2): 113–20. doi:10.1016/S0376-6357(01)00191-7.

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、443頁、448頁

- ^ Warham, John (1990). The Petrels: Their Ecology and Breeding Systems. London: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-735420-4

- ^ Jones, Darryl N.; Dekker, René W.R.J.; Roselaar, Cees S. (1995). The Megapodes. Bird Families of the World 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854651-3

- ^ ギル 『鳥類学』 (2009)、448頁

- ^ Elliot A. "Family Megapodiidae (Megapodes)". del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J, ed (1994). Handbook of the Birds of the World Volume 2: New World Vultures to Guineafowl. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 84-87334-15-6

- ^ Metz VG, Schreiber EA (2002). "Great Frigatebird (Fregata minor)" In The Birds of North America, No 681, (Poole, A. and Gill, F., eds) The Birds of North America Inc: Philadelphia

- ^ Ekman, J (2006). “Family living amongst birds”. w:Journal of Avian Biology 37 (4): 289–98. doi:10.1111/j.2006.0908-8857.03666.x.

- ^ Cockburn A (1996). “Why do so many Australian birds cooperate? Social evolution in the Corvida”. In Floyd R, Sheppard A, de Barro P. Frontiers in Population Ecology. Melbourne: CSIRO. pp. 21–42

- ^ Cockburn, Andrew (June 2006). “Prevalence of different modes of parental care in birds” (Free full text). Proceedings: Biological Sciences 273 (1592): 1375–83. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3458. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1560291. PMID 16777726 2014年7月13日閲覧。.

- ^ Gaston, Anthony J. (1994). A. Poole and F. Gill. ed. “Ancient Murrelet (Synthliboramphus antiquus)”. The Birds of North America (132).

- ^ Schaefer, HC; Eshiamwata, GW; Munyekenye, FB; Bohning-Gaese, K (2004). “Life-history of two African Sylvia warblers: low annual fecundity and long post-fledging care”. Ibis 146 (3): 427–37. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2004.00276.x.

- ^ Alonso, JC; Bautista, LM; Alonso, JA (2004). “Family-based territoriality vs flocking in wintering common cranes Grus grus"”. w:Journal of Avian Biology 35 (5): 434–44. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2004.03290.x.

- ^ a b Davies, N. B. (2000). Cuckoos, Cowbirds and other Cheats. London: T. & A. D. Poyser. ISBN 0-85661-135-2

- ^ Sorenson, Michael D. (1997). “Effects of intra- and interspecific brood parasitism on a precocial host, the canvasback, Aythya valisineria” (PDF). Behavioral Ecology 8 (2): 153–161. doi:10.1093/beheco/8.2.153 2014年7月20日閲覧。.

- ^ Spottiswoode, C. N.; Colebrook-Robjent, J. F.R. (2007). “Egg puncturing by the brood parasitic Greater Honeyguide and potential host counteradaptations”. Behavioral Ecology 18 (4): 792-799. doi:10.1093/beheco/arm025.

- ^ a b Clout, M. N.; Hay, J. R. (1989). “The importance of birds as browsers, pollinators and seed dispersers in New Zealand forests” (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology 12: 27–33 2014年7月21日閲覧。.

- ^ Gary Stiles, F. (1981). “Geographical Aspects of Bird-Flower Coevolution, with Particular Reference to Central America”. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 68 (2): 323–351. doi:10.2307/2398801. JSTOR 2398801.

- ^ Temeles, Ethan J.; Linhart, Yan B.; Masonjones, Michael; Masonjones, Heather D. (2002). “The Role of Flower Width in Hummingbird Bill Length–Flower Length Relationships” (PDF). Biotropica 34 (1): 68–80 2014年7月21日閲覧。.

- ^ Bond, William J.; Lee, William G.; Craine, Joseph M. (2004). “Plant structural defences against browsing birds: a legacy of New Zealand's extinct moas”. Oikos 104 (3): 500–08. doi:10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.12720.x.

- ^ Wainright, S. C.; Haney, J. C.; Kerr, C.; Golovkin, A. N.; Flint, M. V. (1998). “Utilization of nitrogen derived from seabird guano by terrestrial and marine plants at St. Paul, Pribilof Islands, Bering Sea, Alaska”. Marine Ecology 131 (1): 63–71.

- ^ Bosman, A. L.; Hockey, P. A. R. (1986). “Seabird guano as a determinant of rocky intertidal community structure” (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series 32: 247–257. doi:10.3354/meps032247 2014年7月21日閲覧。.

- ^ Bonney, Rick; Rohrbaugh, Jr., Ronald (2004). Handbook of Bird Biology (Second ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-938027-62-X

- ^ Singer, R.; Yom-Tov, Y. (1988). “The Breeding Biology of the House Sparrow Passer domesticus in Israel”. Ornis Scandinavica 19 (2): 139–44. doi:10.2307/3676463. JSTOR 3676463.

- ^ Dolbeer, R. A. (1990). “Ornithology and integrated pest management: Red-winged blackbirds Agleaius phoeniceus and corn”. Ibis 132 (2): 309–322. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1990.tb01048.x.

- ^ Dolbeer, Richard A.; Belant, Jerrold L.; Sillings, Janet L. (1993). “Shooting Gulls Reduces Strikes with Aircraft at John F. Kennedy International Airport” (PDF). Wildlife Society Bulletin 21: 442–450.

- ^ Reed, KD; Meece, JK; Henkel, JS; Shukla, SK (2003). “Birds, migration and emerging zoonoses: west nile virus, lyme disease, influenza a and enteropathogens”. Clinical medicine & research 1 (1): 5–12. doi:10.3121/cmr.1.1.5. PMC 1069015. PMID 15931279.

- ^ Brown, Lester (2005). “3: Moving Up the Food Chain Efficiently.”. Outgrowing the Earth: The Food Security Challenge in an Age of Falling Water Tables and Rising Temperatures. earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84407-185-2 2014年7月23日閲覧。

- ^ “Shifting protein sources: Chapter 3: Moving Up the Food Chain Efficiently.”. Earth Policy Institute. 2014年7月23日閲覧。

- ^ Simeone, Alejandro; Navarro, Ximena (2002). “Human exploitation of seabirds in coastal southern Chile during the mid-Holocene”. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat 75 (2): 423–31. doi:10.4067/S0716-078X2002000200012 2014年7月26日閲覧。.

- ^ a b Keane, Aidan; Brooke, M.de L.; McGowan, P.J.K. (2005). “Correlates of extinction risk and hunting pressure in gamebirds (Galliformes)”. Biological Conservation 126 (2): 216–233. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.05.011.

- ^ Hamilton, Sheryl (2000). “How precise and accurate are data obtained using an infra-red scope on burrow-nesting sooty shearwaters Puffinus griseus?” (PDF). Marine Ornithology 28 (1): 1–6 2014年7月26日閲覧。.

- ^ “The Guano War of 1865–1866”. World History at KMLA. 2014年7月26日閲覧。

- ^ Cooney, Rosie; Jepson, Paul (2006). “The international wild bird trade: what's wrong with blanket bans?”. Oryx 40 (1): 18–23. doi:10.1017/S0030605306000056.

- ^ Manzi, Maya; Coomes, Oliver T. (2002). “Cormorant fishing in Southwestern China: a Traditional Fishery under Siege. (Geographical Field Note)”. Geographic Review 92 (4): 597–603. doi:10.2307/4140937. JSTOR 4140937. オリジナルの2012-05-29時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ INC, SANKEI DIGITAL. “空港で勤務する鷹、その仕事内容は…”. 産経フォト. 2023年1月9日閲覧。

- ^ 日経クロステック(xTECH). “500羽のカラスをタカで追い払う、鷹匠がメガソーラーで大活躍”. 日経クロステック(xTECH). 2023年1月9日閲覧。

- ^ “鷹匠みさと、21歳の春”. RKBオンライン. 2023年1月9日閲覧。

- ^ Pullis La Rouche, Genevieve (2006). G.C. Boere, C.A. Galbraith and D.A. Stroud. ed. “Birding in the United States: a demographic and economic analysis” (PDF). Waterbirds around the world (JNCC.gov.uk) (Edinburgh, UK: Stationery Office): 841–846.

- ^ 山田仁史「媒介者としての鳥 - その神話とシンボリズム」『BIOSTORY (ビオストーリー)』第20号、誠文堂新光社、2013年11月26日、ISBN 978-4-416-11314-1。 [要ページ番号]

- ^ Routledge, Scoresby; Routledge, Katherine (1917). “The Bird Cult of Easter Island”. Folklore 28 (4): 337–355.

- ^ Chapell, Jackie (2006). “Living with the Trickster: Crows, Ravens, and Human Culture” (PDF). PLoS Biology 4 (1): 16–17. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040014 2014年7月27日閲覧。.

- ^ Ingersoll, Ernest (1923). Birds in legend, fable and folklore. Longmans, Green and co. p. 214

- ^ Hauser, Alan Jon (1985). “Jonah: In Pursuit of the Dove”. Journal of Biblical Literature (The Society of Biblical Literature) 104 (1): 21–37. doi:10.2307/3260591. JSTOR 3260591.

- ^ Thankappan Nair, P. (1974). “The Peacock Cult in Asia”. Asian Folklore Studies 33 (2): 93–170. doi:10.2307/1177550. JSTOR 1177550.

- ^ Tennyson, Alan『Extinct Birds of New Zealand』Te Papa Press、Wellington、2006年。ISBN 978-0-909010-21-8。

- ^ Meighan, Clement W. (1966). “Prehistoric Rock Paintings in Baja California”. American Antiquity 31 (3): 372–392. doi:10.2307/2694739. JSTOR 2694739.

- ^ Clarke, Caspar Purdon (1908). “A Pedestal of the Platform of the Peacock Throne”. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 3 (10): 182–183. doi:10.2307/3252550. JSTOR 3252550.

- ^ Boime, Albert (1999). “John James Audubon: a birdwatcher's fanciful flights”. Art History 22 (5): 728–755. doi:10.1111/1467-8365.00184.

- ^ Chandler, Albert R. (1934). “The Nightingale in Greek and Latin Poetry”. The Classical Journal 30 (2): 78–84.

- ^ Lasky, Edward D. (1992). “A Modern Day Albatross: The Valdez and Some of Life's Other Spills”. The English Journal 81 (3): 44–46. doi:10.2307/820195. JSTOR 820195.

- ^ Carson, A. Scott (1998). “Vulture Investors, Predators of the 90s: An Ethical Examination”. Journal of Business Ethics 17 (5): 543–555.

- ^ Enriquez, Paula L.; Mikkola, Heimo (1997). “Comparative study of general public owl knowledge in Costa Rica, Central America and Malawi, Africa” (PDF). Biology and conservation of owls of the Northern Hemisphere. General Technical Report NC-190. 2nd Owl Symposium (St. Paul, Minnesota: USDA Forest Service) 2014年7月27日閲覧。.

- ^ Lewis, Deane (2005年). “Owls in Mythology & Culture”. The Owl Pages. Owlpages.com. 2014年7月27日閲覧。

- ^ Dupree, Hatch (1974). “An Interpretation of the Role of the Hoopoe in Afghan Folklore and Magic”. Folklore 85 (3): 173–193.

- ^ ピーターソン『鳥類』 (1971)、176頁

- ^ Fuller, Errol (2000). Extinct Birds (2nd. ed.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850837-9

- ^ Steadman, David (2006). Extinction & Biogeography of Tropical Pacific Birds. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77142-7

- ^ “BirdLife International announces more Critically Endangered birds than ever before”. Birdlife International (2009年5月14日). 2009年5月15日閲覧。

- ^ Kinver, Mark (2009年5月13日). “Birds at risk reach record high”. BBC News Online 2014年7月28日閲覧。

- ^ Norris K, Pain D, ed (2002). Conserving Bird Biodiversity: General Principles and their Application. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78949-3

- ^ Brothers, Nigel (1991). “Albatross mortality and associated bait loss in the Japanese longline fishery in the Southern Ocean”. Biological Conservation 55 (3): 255–268. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(91)90031-4.

- ^ Wurster, D. H.; Wurster, C. F.; Strickland, W. N. (1965). “Bird Mortality Following DDT Spray for Dutch Elm Disease”. Ecology 46 (4): 488–499. doi:10.2307/1934880.; Wurster, C. F.; Wurster, D. H.; Strickland, W. N. (1965). “Bird Mortality after Spraying for Dutch Elm Disease with DDT”. Science 148 (3666): 90–91. doi:10.1126/science.148.3666.90.

- ^ Blackburn, Tim M.; Cassey, Phillp; Duncan, Richard P.; Evans, Karl L.; Gaston, Kevin J. (2004). “Avian Extinction and Mammalian Introductions on Oceanic Islands”. Science 305 (5692): 1955–58. doi:10.1126/science.1101617. PMID 15448269.

- ^ Butchart, Stuart H.M.; Stattersfield, Alison J.; Collar, Nigel J. (2006). “How many bird extinctions have we prevented?”. Oryx 40 (3): 266–278. doi:10.1017/S0030605306000950.

鳥類と同じ種類の言葉

- >> 「鳥類」を含む用語の索引

- 鳥類のページへのリンク