抗酸化物質

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』 (2023/12/14 03:32 UTC 版)

生物化学としての観点

抗酸化物質の類型

| 抗酸化物質 | 活性酸素種 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O2− | H2O2 | •OH | 1O2 | |

| スーパーオキシドジスムターゼ | Yes | No | No | No |

| グルタチオンペルオキシダーゼ | No | Yes | No | No |

| ペルオキシダーゼ | No | Yes | No | No |

| カタラーゼ | No | Yes | No | No |

| アスコルビン酸 (V.C) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| システイン | No | No | Yes | No |

| グルタチオン | No | No | Yes | No |

| (リノール酸⇒過酸化脂質) | No | No | Yes | No |

| α-トコフェロール (V.E) | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| α-カロテン | No | No | Yes | No |

| β-カロテン | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| フラボノイド | No | No | Yes | No |

| リボフラビン (B2) | No | No | No | Yes |

| ビリルビン | Yes | No | No | No |

| 尿酸 | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| メラトニン | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 水素[33] | No | No | Yes | No |

抗酸化物質にはビタミンCやEのように、酸素が関与する有害な反応を単独で抑制する物質が知られている。このような抗酸化物質は低分子の抗酸化物質に多く認められ、多くの場合は酸素ラジカルあるいはそれから派生したラジカルを停止させる反応を起こす。低分子抗酸化物質の多くは容易に酸化される良い還元剤であるため、直接ラジカルと反応するだけでなく、後述するように酵素が関与する抗酸化反応を補助する場合も多い。低分子の抗酸化物質が直接に反応に関与する場合は反応の選択性は低く、様々なオキシダントと抗酸化物質とが反応する。一方、酵素が関与する抗酸化反応は酵素により反応するオキシダントが決定され、低分子の抗酸化物質は還元剤としての役割を果たす[16]。

高分子の抗酸化物質は大きく分けるとオキシターゼとミネラル輸送・貯蔵タンパク質とに大別することができる。すなわち生体内には多種多様なオキシダーゼが存在し、活性酸素種自体を基質として代謝する酵素もあれば、発生した有害な過酸化物を分解代謝する酵素もある。またオキシダントと反応して酸化型となったビタミンCやEのような『活性を失った抗酸化物質』を、還元型に戻してリサイクルする酵素も存在する。したがって、直接あるいはリサイクルに関与し間接的に抗酸化作用を示す一部のオキシダーゼも抗酸化物質の一つと見なされる[16]。

このような抗酸化物質と見なされるオキシダーゼの多くはグルタチオンやビタミンC といった電子受容体を基質として消費する。すなわち酵素による過酸化物質の代謝には還元剤としての抗酸化物質の存在が必須である。これは「酵素反応は可逆反応であり、ただ反応速度を増大させるのみである」という酵素の特性に留意する必要がある。つまり生体内では電子受容体が豊富に存在するために逆反応は問題にはならない。しかし、栄養学や食品科学など非生体的な条件下においては、条件によっては生体では抗酸化物質と見なされるオキシダーゼであっても、食品に加工された状態においては酸素が関与する逆反応を加速することで抗酸化物質を消費し尽したり、活性酸素種を発生させ、それにより食品の鮮度、品質を低下させる場合もある[16][34]。

これらのオキシダーゼの多くは酵素活性中心には微量ミネラルである、鉄、マンガン、銅、セレン原子などが存在している。これらの金属元素は容易に酸化還元反応を受けやすい[35]。

一方、これらの微量ミネラルの体内でのADMEは特定の酸化状態であることが必要である。たとえば、鉄は鉄 (III) イオンは特定の膜トランスポーターに依存するので生体に吸収されないが[36]、鉄 (II) イオンがキレート(ラクトフェリンのように高分子の場合もあればクエン酸など低分子の場合もある)を形成して取り込まれる。さらに体内ではトランスフェリンは鉄 (III) イオンに結合して貯蔵、輸送される。このような酸化状態の特異性は、ほかの微量ミネラルでも同様に見ることができる。つまり、微量ミネラルは低分子あるいは特定のタンパク質がキレートすることで、それぞれの状況に有利な酸化状態で輸送、貯蔵される。微量ミネラル元素でも鉄イオンは酵素と結合して酵素補欠因子にならなくても、生体内の環境で金属イオンが酸化還元機能を持つ場合もある。しかし多くの場合は微量ミネラルは、生体内の環境では酵素補欠因子として酵素の活性中心に配置されて初めて酸化還元機能をもつ。いずれにしろ微量ミネラル元素を取り込んだオキシターゼは基質特異的に抗酸化作用を触媒するので、微量ミネラル元素はオキシターゼが関与する抗酸化生体システムのカギである。そのオキシターゼの存在量も、微量ミネラル元素を輸送・貯蔵に関与する分子、それは低分子あるいは高分子の微量金属元素をキレートする生体物質であるが、それらのキレート物質が欠乏すれば酵素の存在量を変動させ間接的には生体の抗酸化機能に変動をもたらす[35][34]。したがってトランスフェリンやフェリチンのようなキレート物質は生体システムの観点においては抗酸化物質と見なされる。

活性酸素種と抗酸化物質

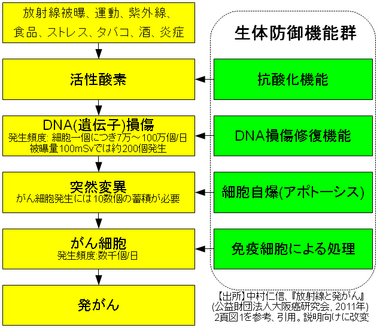

活性酸素種は細胞において過酸化水素 (H2O2) およびヒドロキシルラジカル (·OH) とスーパーオキシドアニオン (O−

2) のようなフリーラジカルを形成する[37][38][39]。ヒドロキシルラジカルは特に不安定であり、即座に非特異的に多くの生体分子との反応を起こす。この化学種はフェントン反応のような金属触媒酸化還元反応によって過酸化水素から形成する[40]。これらの酸化物質は化学的連鎖反応を開始させることにより脂肪やDNA、タンパク質を酸化させ細胞を損傷させる[5]。DNA修復機構は稀な頻度で修復ミスを発生するので突然変異や癌の原因となり[41][42]、タンパク質への損傷は酵素阻害、変性、タンパク質分解の原因となる[43]。

電子伝達系など代謝エネルギーの合成機構において酸素が使われる局所では副反応として活性酸素種が発生する[44]。つまりスーパーオキシドアニオンが電子伝達系において副生成物として生成する[45]。特に重要なのは複合体III による補酵素Qの還元で、中間体として高反応性フリーラジカル (Q·−) が形成する。この不安定中間体は電子の"漏出"を誘導し、通常の電子伝達系の反応ではなく電子が直接酸素に転移し、スーパーオキシドアニオンを形成させる[46]。また、ペルオキシドは複合体Iでの還元型フラボタンパク質の酸化からも発生する[47]。これらの酵素群は酸化物質を合成することができるが、ペルオキシドを形成するその他の過程への電子伝達系の相対的重要性は不明である[48][49]。また、植物、藻類、藍藻類では、活性酸素種は光合成の間に生じるが[50]、特に高光度条件のときに生成する[50]。この効果は光阻害ではカロテノイドにより相殺されるが、それには抗酸化物質と過還元状態の光合成反応中心との反応が伴い、活性酸素種の形成を防いでいる[51][52]。

抗酸化物質の生体内分布

| 抗酸化代謝物 | 溶解性 | ヒトの血清中での濃度 (μM)[53] | 肝組織での濃度 (μmol/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| アスコルビン酸 (ビタミンC) |

水溶性 | 50 – 60[54] | 260(ヒト)[55] |

| グルタチオン | 水溶性 | 4[56] | 6,400(ヒト)[55] |

| リポ酸 | 水溶性 | 0.1 – 0.7[57] | 4 – 5(ラット)[58] |

| 尿酸 | 水溶性 | 200 – 400[59] | 1,600(ヒト)[55] |

| ウロビリノーゲン | 水溶性 | 3 – 13[60] | 不明 |

| ビリルビン | 脂溶性 | 5 – 17[61] | 不明 |

| カロテン類 | 脂溶性 | β-カロテン: 0.5 – 1[62] |

5 [64](ヒト、総カロテノイド) |

| α-トコフェロール (ビタミンE) |

脂溶性 | 10 – 40[63] | 50 [55](ヒト) |

| ユビキノール (補酵素Q) |

脂溶性 | 5[65] | 200(ヒト)[66] |

抗酸化物質は水溶性と脂溶性の2つに大きく分けられる。一般に、水溶性抗酸化物質は細胞質基質と血漿中の酸化物質と反応し、脂溶性抗酸化物質は細胞膜の脂質過酸化反応を防止している[5]。これらの化合物は体内で生合成するか、食物からの摂取によって得られる[9]。それぞれの抗酸化物質は様々な濃度で体液や組織に存在している。グルタチオンやユビキノンなどは主に細胞内に存在しているのに対し尿酸はより広範囲に分布している(下表参照)。稀少種でしか見られない抗酸化物質もあり、それらは病原菌にとって重要であったり、毒性因子となったりする[67]。

様々な代謝物と酵素系はそれぞれ相乗効果と相互依存効果を有するが、抗酸化物質の特定の場合における重要性と相互作用は不明である[68][69]。したがって、一種の抗酸化物質は抗酸化物質系の他の構成要素の機能に依存している可能性がある[9]。また、抗酸化物質によって保護される度合いはその濃度、反応性、反応環境の影響を受ける[9]。

いくつかの化合物は遷移金属をキレートすることによって細胞内で触媒生成するフリーラジカルによる酸化を抑制している。特にトランスフェリンやフェリチンのような鉄結合タンパク質は、キレート化することにより鉄の酸化を抑制している[70]。セレンと亜鉛は一般的に抗酸化栄養素と呼ばれているが元素自体は抗酸化能を持たず、抗酸化酵素と結合することによって抗酸化能を持つ。

酵素と抗酸化物質

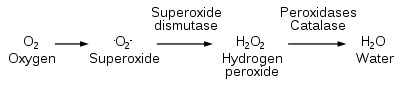

化学的酸化防止剤と同様に、細胞は抗酸化酵素の相互作用網によって酸化ストレスから保護されている[5][8]。酸化的リン酸化のようなプロセスによって遊離される超酸化物は最初に過酸化水素に変換され、さらなる還元を受け最終的に水となる。この解毒経路はスーパーオキシドジスムターゼやカタラーゼ、ペルオキシダーゼなど多数の酵素によるものである。

抗酸化代謝体と同様に、抗酸化防衛における酵素の寄与を互いに切り離して考えることは難しいが、抗酸化酵素を1つだけ欠損させた遺伝子導入マウスを作ることそので情報を得ることができる[71]。

スーパーオキシドディスムターゼ、カタラーゼおよびペルオキシレドキシン

スーパーオキシドディスムターゼ (SOD) は、スーパーオキシドアニオンを酸素と過酸化水素に分解する酵素群である[72][73]。SODはほとんど全ての好気性細胞と細胞外液に存在する[74]。酸素が存在することによって細胞内に形成される致死性のスーパーオキシドを変化させるスーパーオキシドディスムターゼやカタラーゼを欠くことにより、偏性嫌気性生物は酸素の存在下で死滅することとなる[75]。

SOD はそのアイソザイムによって、銅、亜鉛、マンガン、および鉄を補因子として含む。ヒトを初めとした哺乳動物や多くの脊椎動物は、3種の SOD (SOD1, SOD2, SOD3) を持ち、銅/亜鉛を含む SOD1 と 3 はそれぞれ細胞質と細胞外空間に、マンガンを含む SOD2 はミトコンドリアに存在する[73][76]。ヒトは鉄を補因子とした SOD は持たない。3種の SOD のうち、ミトコンドリアアイソザイム (SOD2) は最も生物学的に重要で、マウスはこの酵素が欠損すると生後間もなく死亡する[77]。一方、銅/亜鉛SOD (SOD1) 欠損マウスは生存能力はあるが多くは病的で低寿命(超酸化物を参照)であり、細胞外液SOD (SOD3) 欠損マウスは異常は最小限(酸素過剰症に過敏)である[71][78]。植物では、SOD のアイソザイムは細胞質とミトコンドリアに存在し、葉緑体では脊椎動物と酵母菌にはない鉄SOD が見られる[79]。

カタラーゼは鉄とマンガンを補因子として用いて過酸化水素を水と酸素に変換する酵素である[80][81]。このタンパク質はほとんどの真核細胞のペルオキシソームに局在している[82]。カタラーゼは基質が過酸化水素だけである独特な酵素で、ピンポン機構を示す。まず補因子が一分子の過酸化水素で酸化され、生成した酸素を二番目の基質へ転移させることにより補因子が再生する[83]。過酸化水素の除去は明らかに重要であるのにもかかわらず、遺伝的なカタラーゼの欠損(無カタラーゼ症)のヒト、もしくは遺伝子組み換えで無カタラーゼにしたマウスの苦痛を感じる病的影響はほとんどない[84][85]。

ペルオキシレドキシン類は過酸化水素やペルオキシ亜硝酸など有機ヒドロペルペルオキシドの還元を触媒するペルオキシダーゼ類である[87]。ペルオキシレドキシンは、典型的な2-システインペルオキシレドキシン、非定型な 2-システインペルオキシレドキシン、1-システインペルオキシレドキシンの3種に分けられる[88]。これらの酵素は基本的に触媒機構は同じで、活性部位の酸化還元活性システイン (peroxidatic cysteine) は基質であるペルオキシドによってスルフェン酸に酸化される[89]。このシステイン残基の過酸化により酵素は不活性化するが、スルフィレドキシンの作用によって再生される[90]。ペルオキシレドキシン1および2を欠損させたマウスでは低寿命化や溶血性貧血が起こり、植物ではペルオキシレドキシン葉緑体で発生した過酸化水素の除去に使われるため、ペルオキシレドキシンは抗酸化代謝において重要である[91][92][93]。

チオレドキシン系とグルタチオン系

チオレドキシン系は12kDa のタンパク質であるチオレドキシンと、それに随伴するチオレドキシンレダクターゼからなる[94]。チオレドキシン関連のタンパク質は、シロイヌナズナのような植物も含めてゲノムプロジェクトが完了した全ての生物に存在しており、特にシロイヌナズナでは多様なアイソフォームが見られる[95]。チオレドキシンの活性部位には、保存性の高い CXXCモチーフの中に2つの近接したシステイン残基が含まれている。これにより活性部位は遊離の2つのチオール基を持つ活性型(還元型)と、ジスルフィド結合が形成された酸化型とを可逆的に移り変わることができる。活性型のチオレドキシンは効果的な還元剤として振る舞い、活性酸素種を除去することにより他のタンパク質の還元状態を保つ[96]。酸化されたチオレドキシンは、NADPH を電子供与体としてチオレドキシンレダクターゼによって還元型へと再生される[97]。

グルタチオン系には、グルタチオンとグルタチオンレダクターゼ、グルタチオンペルオキシダーゼおよびグルタチオン S-トランスフェラーゼが含まれる[98]。この系は動物、植物および微生物で見られる[98][99]。グルタチオンペルオキシダーゼは補因子として4つのセレン原子を含み、過酸化水素と有機ヒドロペルオキシドの分解を触媒する。動物では少なくとも4種のグルタチオンペルオキシダーゼのアイソザイムがある[100]。グルタチオンペルオキシダーゼ1は最も豊富で、効率的に過酸化水素を除去する。一方、グルタチオンペルオキシダーゼ4は脂質ヒドロペルオキシドに作用する。意外にも、グルタチオンペルオキシダーゼ1はなくとも問題はなく、この酵素を欠損させたマウスは正常寿命である[101]。しかし、グルタチオンペルオキシダーゼ1欠損マウスは酸化ストレスに過敏である[102]。グルタチオン S-トランスフェラーゼについては過酸化脂質に対し高活性が見られる[103]。これらの酵素は肝臓に高濃度で存在し、また解毒作用を持つ[104]。

- ^ 井上圭三, 今堀和友 & 山川民夫 1998, p. 498.

- ^ 井上圭三, 今堀和友 & 山川民夫 1998, p. 1108.

- ^ a b 井上圭三, 今堀和友 & 山川民夫 1998, p. 425.

- ^ a b 井上圭三, 今堀和友 & 山川民夫 1998, p. 498

- ^ a b c d e Sies H (1997). “Oxidative stress: oxidants and antioxidants”. Exp Physiol 82 (2): 291–5. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004024. PMID 9129943.

- ^ Rhee SG (June 2006). “Cell signaling. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling”. Science (journal) 312 (5782): 1882–3. doi:10.1126/science.1130481. PMID 16809515.

- ^ a b c “「活性酸素シグナル伝達の分子機構」について”. 大阪大学 蛋白質研究所 細胞内シグナル伝達研究室. 2011年2月3日閲覧。[リンク切れ]

- ^ a b Davies K (1995). “Oxidative stress: the paradox of aerobic life”. Biochem Soc Symp 61: 1–31. PMID 8660387.

- ^ a b c d Vertuani S, Angusti A, Manfredini S (2004). “The antioxidants and pro-antioxidants network: an overview”. Curr Pharm Des 10 (14): 1677–94. doi:10.2174/1381612043384655. PMID 15134565.

- ^ 吉川春寿 & 芦田淳 1995, p. 183「抗酸化剤」

- ^ a b フェントン試薬、『理化学辞典』、第5版CD-ROM版、岩波書店、1996.

- ^ Fenton H.J.H. (1894). “Oxidation of tartaric acid in presence of iron”. J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 65 (65): 899–911. doi:10.1039/ct8946500899.

- ^ Benzie, IF (2003). “Evolution of dietary antioxidants”. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Part A, Molecular & integrative physiology 136 (1): 113–26. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(02)00368-9. PMID 14527634.

- ^ 重岡成、石川孝博、武田徹「光合成生物における光・酸素毒防御系の分子機構--光・酸素毒耐性植物の創製は可能か」『蛋白質核酸酵素』第43巻第5号、共立出版、1998年4月、634-648頁、NAID 40002332952。

- ^ 井上圭三, 今堀和友 & 山川民夫 1998, p. 600

- ^ a b c d e 吉川春寿, 芦田淳 & 41995, p. 212「抗酸化剤」

- ^ a b 堤 ちはる、「脂肪」、『世界大百科事典』、第二版、CD-ROM版、平凡社 (1998)

- ^ a b 赤池孝章,鈴木敬一郎,内田浩二編著、『活性酸素シグナルと酸化ストレス』、実験医学増刊、Vol.27、No.15、羊土社、2009。ISBN 978-4-7581-0301-5

- ^ 奥田 拓道、『健康・栄養食品事典―機能性食品・特定保健用食品 』、漢方医薬新聞編集部、東洋医学社(2006) ISBN 4-88580-153-2

- ^ Baillie, J K; A A R Thompson, J B Irving, M G D Bates, A I Sutherland, W Macnee, S R J Maxwell, D J Webb (2009-03-09). “Oral antioxidant supplementation does not prevent acute mountain sickness: double blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial”. QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians 102 (5): 341–8. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcp026. ISSN 1460-2393. PMID 19273551 2009年3月25日閲覧。.

- ^ Bjelakovic G; Nikolova, D; Gluud, LL; Simonetti, RG; Gluud, C (2007). “Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis”. JAMA 297 (8): 842–57. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.842. PMID 17327526.

- ^ Matill HA (1947). Antioxidants. Annu Rev Biochem 16: 177–192.

- ^ 冨永 博夫、「潤滑油」、『世界大百科事典』、第二版CD-ROM版、平凡社、1998.

- ^ Jacob R (1996). “Three eras of vitamin C discovery”. Subcell Biochem 25: 1–16. PMID 8821966.

- ^ Knight J (1998). “Free radicals: their history and current status in aging and disease”. Ann Clin Lab Sci 28 (6): 331–46. PMID 9846200.

- ^ a b 吉川春寿 & 芦田淳 1995, p. 765-776「栄養学史年表」

- ^ Moreau and Dufraisse, (1922) Comptes Rendus des Séances et Mémoires de la Société de Biologie, 86, 321.

- ^ Wolf G (1 March 2005). “The discovery of the antioxidant function of vitamin E: the contribution of Henry A. Mattill”. J Nutr 135 (3): 363–6. doi:10.1093/jn/135.3.363. PMID 15735064.

- ^ 吉川春寿, 芦田淳 & 1995), p. 613「ビタミンE」

- ^ German J (1999). “Food processing and lipid oxidation”. Adv Exp Med Biol 459: 23–50. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4853-9_3. PMID 10335367.

- ^ 大阪武雄、日本化学会『活性酸素』丸善、1999年、p.27頁。ISBN 4-621-04634-9。

- ^ a b 服部淳彦「メラトニンとエイジング」『比較生理生化学』第34巻第1号、日本比較生理生化学会、2017年、2-11頁、doi:10.3330/hikakuseiriseika.34.2、ISSN 0916-3786、NAID 130006847407。

- ^ 大澤 郁朗、「水素分子の生理作用と水素水による疾患防御」、『日本老年医学会雑誌』 49巻 6 号(2012:11)、p.680

- ^ a b 小城勝相, 中谷延二, 清水誠『食と健康 : 食品の成分と機能』1626418-1-0611号、放送大学教育振興会〈放送大学教材〉、2006年。ISBN 4595306075。 NCID BA76296688。

- ^ a b 原口紘炁『生命と金属の世界』1869299-1-0511号、放送大学教育振興会〈放送大学教材〉、2005年。ISBN 4595305613。 NCID BA71739307。

- ^ 関根孝司. “鉄の腹輪送の分子機構”. 日本薬理学会. 2021年11月29日閲覧。

- ^ a b Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin M, Mazur M, Telser J (2007). “Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease”. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 39 (1): 44–84. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. PMID 16978905.

- ^ 岩井邦久, 西嶋智彦「生体内抗酸化--抗酸化物質の生体利用と活性発現」『食品・食品添加物研究誌』第215巻第1号、FFIジャーナル編集委員会、2010年、pp.38-45、ISSN 09199772、NAID 40017000569。

- ^ 矢澤一良「ヘルスフード科学シリーズ(7)活性酸素と抗酸化物質」『食品と容器』第44巻第9号、缶詰技術研究会 / 缶詰技術研究会、2003年、pp.488-493、ISSN 09112278、NAID 80016098534。

- ^ Stohs S, Bagchi D (1995). “Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions”. Free Radic Biol Med 18 (2): 321–36. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(94)00159-H. PMID 7744317.

- ^ Nakabeppu Y, Sakumi K, Sakamoto K, Tsuchimoto D, Tsuzuki T, Nakatsu Y (2006). “Mutagenesis and carcinogenesis caused by the oxidation of nucleic acids”. Biol Chem 387 (4): 373–9. doi:10.1515/BC.2006.050. PMID 16606334.

- ^ Valko M, Izakovic M, Mazur M, Rhodes C, Telser J (2004). “Role of oxygen radicals in DNA damage and cancer incidence”. Mol Cell Biochem 266 (1–2): 37–56. doi:10.1023/B:MCBI.0000049134.69131.89. PMID 15646026.

- ^ Stadtman E (1992). “Protein oxidation and aging”. Science 257 (5074): 1220–4. doi:10.1126/science.1355616. PMID 1355616.

- ^ Raha S, Robinson B (2000). “Mitochondria, oxygen free radicals, disease and aging”. Trends Biochem Sci 25 (10): 502–8. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01674-1. PMID 11050436.

- ^ Lenaz G (2001). “The mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species: mechanisms and implications in human pathology”. IUBMB Life 52 (3–5): 159–64. doi:10.1080/15216540152845957. PMID 11798028.

- ^ Finkel T, Holbrook NJ (2000). “Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of aging”. Nature 408 (6809): 239–47. doi:10.1038/35041687. PMID 11089981.

- ^ Hirst J, King MS, Pryde KR (October 2008). “The production of reactive oxygen species by complex I”. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36 (Pt 5): 976–80. doi:10.1042/BST0360976. PMID 18793173.

- ^ Seaver LC, Imlay JA (November 2004). “Are respiratory enzymes the primary sources of intracellular hydrogen peroxide?”. J. Biol. Chem. 279 (47): 48742–50. doi:10.1074/jbc.M408754200. PMID 15361522.

- ^ Imlay JA (2003). “Pathways of oxidative damage”. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57: 395–418. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090938. PMID 14527285.

- ^ a b Demmig-Adams B, Adams WW (December 2002). “Antioxidants in photosynthesis and human nutrition”. Science (journal) 298 (5601): 2149–53. doi:10.1126/science.1078002. PMID 12481128.

- ^ Szabó I, Bergantino E, Giacometti G (2005). “Light and oxygenic photosynthesis: energy dissipation as a protection mechanism against photo-oxidation”. EMBO Rep 6 (7): 629–34. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400460. PMC 1369118. PMID 15995679.

- ^ Kerfeld CA (October 2004). “Water-soluble carotenoid proteins of cyanobacteria”. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 430 (1): 2–9. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2004.03.018. PMID 15325905.

- ^ Ames B, Cathcart R, Schwiers E, Hochstein P (1981). “Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: a hypothesis”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78 (11): 6858–62. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.11.6858. PMC 349151. PMID 6947260.

- ^ Khaw K, Woodhouse P (1995). “Interrelation of vitamin C, infection, haemostatic factors, and cardiovascular disease”. BMJ 310 (6994): 1559 – 63. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6994.1559. PMC 2549940. PMID 7787643.

- ^ a b c d Evelson P, Travacio M, Repetto M, Escobar J, Llesuy S, Lissi E (2001). “Evaluation of total reactive antioxidant potential (TRAP) of tissue homogenates and their cytosols”. Arch Biochem Biophys 388 (2): 261 – 6. doi:10.1006/abbi.2001.2292. PMID 11368163.

- ^ Morrison JA, Jacobsen DW, Sprecher DL, Robinson K, Khoury P, Daniels SR (30 November 1999). “Serum glutathione in adolescent males predicts parental coronary heart disease”. Circulation 100 (22): 2244–7. PMID 10577998.

- ^ Teichert J, Preiss R (1992). “HPLC-methods for determination of lipoic acid and its reduced form in human plasma”. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 30 (11): 511 – 2. PMID 1490813.

- ^ Akiba S, Matsugo S, Packer L, Konishi T (1998). “Assay of protein-bound lipoic acid in tissues by a new enzymatic method”. Anal Biochem 258 (2): 299 – 304. doi:10.1006/abio.1998.2615. PMID 9570844.

- ^ a b Glantzounis G, Tsimoyiannis E, Kappas A, Galaris D (2005). “Uric acid and oxidative stress”. Curr Pharm Des 11 (32): 4145 – 51. doi:10.2174/138161205774913255. PMID 16375736.

- ^ Normal Reference Range Table Archived 2011年12月25日, at the Wayback Machine. from The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Used in Interactive Case Study Companion to Pathologic basis of disease.

- ^ Golonka, Debby. “Digestive Disorders Health Center: Bilirubin”. en:WebMD. pp. 3. 2010年1月14日閲覧。

- ^ El-Sohemy A, Baylin A, Kabagambe E, Ascherio A, Spiegelman D, Campos H (2002). “Individual carotenoid concentrations in adipose tissue and plasma as biomarkers of dietary intake”. Am J Clin Nutr 76 (1): 172 – 9. PMID 12081831.

- ^ a b Sowell A, Huff D, Yeager P, Caudill S, Gunter E (1994). “Retinol, alpha-tocopherol, lutein/zeaxanthin, beta-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, alpha-carotene, trans-beta-carotene, and four retinyl esters in serum determined simultaneously by reversed-phase HPLC with multiwavelength detection”. Clin Chem 40 (3): 411 – 6. PMID 8131277.

- ^ Stahl W, Schwarz W, Sundquist A, Sies H (1992). “cis-trans isomers of lycopene and beta-carotene in human serum and tissues”. Arch Biochem Biophys 294 (1): 173 – 7. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(92)90153-N. PMID 1550343.

- ^ Zita C, Overvad K, Mortensen S, Sindberg C, Moesgaard S, Hunter D (2003). “Serum coenzyme Q10 concentrations in healthy men supplemented with 30 mg or 100 mg coenzyme Q10 for two months in a randomised controlled study”. Biofactors 18 (1 – 4): 185 – 93. doi:10.1002/biof.5520180221. PMID 14695934.

- ^ a b Turunen M, Olsson J, Dallner G (2004). “Metabolism and function of coenzyme Q”. Biochim Biophys Acta 1660 (1 – 2): 171 – 99. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.11.012. PMID 14757233.

- ^ Miller RA, Britigan BE (January 1997). “Role of oxidants in microbial pathophysiology”. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10 (1): 1–18. PMC 172912. PMID 8993856.

- ^ Chaudière J, Ferrari-Iliou R (1999). “Intracellular antioxidants: from chemical to biochemical mechanisms”. Food Chem Toxicol 37 (9–10): 949 – 62. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(99)00090-3. PMID 10541450.

- ^ Sies H (1993). “Strategies of antioxidant defense”. Eur J Biochem 215 (2): 213 – 9. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18025.x. PMID 7688300.

- ^ Imlay J (2003). “Pathways of oxidative damage”. Annu Rev Microbiol 57: 395–418. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090938. PMID 14527285.

- ^ a b Ho YS, Magnenat JL, Gargano M, Cao J (1 October 1998). “The nature of antioxidant defense mechanisms: a lesson from transgenic studies”. Environ. Health Perspect. 106 (Suppl 5): 1219–28. doi:10.2307/3433989. PMC 1533365. PMID 9788901.

- ^ Zelko I, Mariani T, Folz R (2002). “Superoxide dismutase multigene family: a comparison of the CuZn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and EC-SOD (SOD3) gene structures, evolution, and expression”. Free Radic Biol Med 33 (3): 337–49. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00905-X. PMID 12126755.

- ^ a b Bannister J, Bannister W, Rotilio G (1987). “Aspects of the structure, function, and applications of superoxide dismutase”. CRC Crit Rev Biochem 22 (2): 111–80. doi:10.3109/10409238709083738. PMID 3315461.

- ^ Johnson F, Giulivi C (2005). “Superoxide dismutases and their impact upon human health”. Mol Aspects Med 26 (4–5): 340–52. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.006. PMID 16099495.

- ^ “アーカイブされたコピー”. 2011年7月9日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2011年2月26日閲覧。

- ^ Nozik-Grayck E, Suliman H, Piantadosi C (2005). “Extracellular superoxide dismutase”. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 37 (12): 2466–71. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2005.06.012. PMID 16087389.

- ^ Melov S, Schneider J, Day B, Hinerfeld D, Coskun P, Mirra S, Crapo J, Wallace D (1998). “A novel neurological phenotype in mice lacking mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase”. Nat Genet 18 (2): 159–63. doi:10.1038/ng0298-159. PMID 9462746.

- ^ Reaume A, Elliott J, Hoffman E, Kowall N, Ferrante R, Siwek D, Wilcox H, Flood D, Beal M, Brown R, Scott R, Snider W (1996). “Motor neurons in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase-deficient mice develop normally but exhibit enhanced cell death after axonal injury”. Nat Genet 13 (1): 43–7. doi:10.1038/ng0596-43. PMID 8673102.

- ^ Van Camp W, Inzé D, Van Montagu M (1997). “The regulation and function of tobacco superoxide dismutases”. Free Radic Biol Med 23 (3): 515–20. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(97)00112-3. PMID 9214590.

- ^ Chelikani P, Fita I, Loewen P (2004). “Diversity of structures and properties among catalases”. Cell Mol Life Sci 61 (2): 192–208. doi:10.1007/s00018-003-3206-5. PMID 14745498.

- ^ Zámocký M, Koller F (1999). “Understanding the structure and function of catalases: clues from molecular evolution and in vitro mutagenesis”. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 72 (1): 19–66. doi:10.1016/S0079-6107(98)00058-3. PMID 10446501.

- ^ del Río L, Sandalio L, Palma J, Bueno P, Corpas F (1992). “Metabolism of oxygen radicals in peroxisomes and cellular implications”. Free Radic Biol Med 13 (5): 557–80. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(92)90150-F. PMID 1334030.

- ^ Hiner A, Raven E, Thorneley R, García-Cánovas F, Rodríguez-López J (2002). “Mechanisms of compound I formation in heme peroxidases”. J Inorg Biochem 91 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1016/S0162-0134(02)00390-2. PMID 12121759.

- ^ Mueller S, Riedel H, Stremmel W (15 December 1997). “Direct evidence for catalase as the predominant H2O2 -removing enzyme in human erythrocytes”. Blood 90 (12): 4973–8. PMID 9389716.

- ^ Ogata M (1991). “Acatalasemia”. Hum Genet 86 (4): 331–40. doi:10.1007/BF00201829. PMID 1999334.

- ^ Parsonage D, Youngblood D, Sarma G, Wood Z, Karplus P, Poole L (2005). “Analysis of the link between enzymatic activity and oligomeric state in AhpC, a bacterial peroxiredoxin”. Biochemistry 44 (31): 10583–92. doi:10.1021/bi050448i. PMID 16060667. PDB 1YEX

- ^ Rhee S, Chae H, Kim K (2005). “Peroxiredoxins: a historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling”. Free Radic Biol Med 38 (12): 1543–52. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.026. PMID 15917183.

- ^ Wood Z, Schröder E, Robin Harris J, Poole L (2003). “Structure, mechanism and regulation of peroxiredoxins”. Trends Biochem Sci 28 (1): 32–40. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(02)00003-8. PMID 12517450.

- ^ Claiborne A, Yeh J, Mallett T, Luba J, Crane E, Charrier V, Parsonage D (1999). “Protein-sulfenic acids: diverse roles for an unlikely player in enzyme catalysis and redox regulation”. Biochemistry 38 (47): 15407–16. doi:10.1021/bi992025k. PMID 10569923.

- ^ Jönsson TJ, Lowther WT (2007). “The peroxiredoxin repair proteins”. Sub-cellular biochemistry 44: 115–41. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6051-9_6. PMC 2391273. PMID 18084892.

- ^ Neumann C, Krause D, Carman C, Das S, Dubey D, Abraham J, Bronson R, Fujiwara Y, Orkin S, Van Etten R (2003). “Essential role for the peroxiredoxin Prdx1 in erythrocyte antioxidant defence and tumour suppression”. Nature 424 (6948): 561–5. doi:10.1038/nature01819. PMID 12891360.

- ^ Lee T, Kim S, Yu S, Kim S, Park D, Moon H, Dho S, Kwon K, Kwon H, Han Y, Jeong S, Kang S, Shin H, Lee K, Rhee S, Yu D (2003). “Peroxiredoxin II is essential for sustaining life span of erythrocytes in mice”. Blood 101 (12): 5033–8. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-08-2548. PMID 12586629.

- ^ Dietz K, Jacob S, Oelze M, Laxa M, Tognetti V, de Miranda S, Baier M, Finkemeier I (2006). “The function of peroxiredoxins in plant organelle redox metabolism”. J Exp Bot 57 (8): 1697–709. doi:10.1093/jxb/erj160. PMID 16606633.

- ^ Nordberg J, Arner ES (2001). “Reactive oxygen species, antioxidants, and the mammalian thioredoxin system”. Free Radic Biol Med 31 (11): 1287–312. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00724-9. PMID 11728801.

- ^ Vieira Dos Santos C, Rey P (2006). “Plant thioredoxins are key actors in the oxidative stress response”. Trends Plant Sci 11 (7): 329–34. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2006.05.005. PMID 16782394.

- ^ Arnér E, Holmgren A (2000). “Physiological functions of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase”. Eur J Biochem 267 (20): 6102–9. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01701.x. PMID 11012661.

- ^ Mustacich D, Powis G (2000). “Thioredoxin reductase”. Biochem J 346 (Pt 1): 1–8. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3460001. PMC 1220815. PMID 10657232.

- ^ a b c d Meister A, Anderson M (1983). “Glutathione”. Annu Rev Biochem 52: 711 – 60. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431. PMID 6137189.

- ^ Creissen G, Broadbent P, Stevens R, Wellburn A, Mullineaux P (1996). “Manipulation of glutathione metabolism in transgenic plants”. Biochem Soc Trans 24 (2): 465–9. PMID 8736785.

- ^ Brigelius-Flohé R (1999). “Tissue-specific functions of individual glutathione peroxidases”. Free Radic Biol Med 27 (9–10): 951–65. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00173-2. PMID 10569628.

- ^ Ho Y, Magnenat J, Bronson R, Cao J, Gargano M, Sugawara M, Funk C (1997). “Mice deficient in cellular glutathione peroxidase develop normally and show no increased sensitivity to hyperoxia”. J Biol Chem 272 (26): 16644–51. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.26.16644. PMID 9195979.

- ^ de Haan J, Bladier C, Griffiths P, Kelner M, O'Shea R, Cheung N, Bronson R, Silvestro M, Wild S, Zheng S, Beart P, Hertzog P, Kola I (1998). “Mice with a homozygous null mutation for the most abundant glutathione peroxidase, Gpx1, show increased susceptibility to the oxidative stress-inducing agents paraquat and hydrogen peroxide”. J Biol Chem 273 (35): 22528–36. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.35.22528. PMID 9712879.

- ^ Sharma R, Yang Y, Sharma A, Awasthi S, Awasthi Y (2004). “Antioxidant role of glutathione S-transferases: protection against oxidant toxicity and regulation of stress-mediated apoptosis”. Antioxid Redox Signal 6 (2): 289–300. doi:10.1089/152308604322899350. PMID 15025930.

- ^ Hayes J, Flanagan J, Jowsey I (2005). “Glutathione transferases”. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 45: 51–88. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857. PMID 15822171.

- ^ Becker BF (June 1993). “Towards the physiological function of uric acid”. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 14 (6): 615–31. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(93)90143-I. PMID 8325534.

- ^ 霊長類の進化による尿酸分解活性の消失 I ヒト上科祖先での尿酸オキシダーゼの消滅Friedman TB, Polanco GE, Appold JC, Mayle JE (1985). “On the loss of uricolytic activity during primate evolution--I. Silencing of urate oxidase in a hominoid ancestor”. Comp. Biochem. Physiol., B 81 (3): 653?9. PMID 3928241.

- ^ Purine and Pyrimidine Metabolism (Eccles Health Sciences Library)

- ^ a b Peter Proctor Similar Functions of Uric Acid and Ascorbate in ManSimilar Functions of Uric Acid and Ascorbate in Man Nature vol 228, 1970, p868.

- ^ 藤森 新「高尿酸血症と心血管リスク」『綜合臨床』第59巻第2号、永井書店、2010年、pp.251-256、ISSN 03711900、NAID 40016985298。

- ^ a b Dimitroula HV, Hatzitolios AI, Karvounis HI (July 2008). “The role of uric acid in stroke: the issue remains unresolved”. Neurologist 14 (4): 238–42. doi:10.1097/NRL.0b013e31815c666b. PMID 18617849.

- ^ a b Strazzullo P, Puig JG (July 2007). “Uric acid and oxidative stress: relative impact on cardiovascular risk?”. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 17 (6): 409–14. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2007.02.011. PMID 17643880.

- ^ Baillie, J.K.; M.G. Bates, A.A. Thompson, W.S. Waring, R.W. Partridge, M.F. Schnopp, A. Simpson, F. Gulliver-Sloan, S.R. Maxwell,D.J. Webb (2007-05). “Endogenous urate production augments plasma antioxidant capacity in healthy lowland subjects exposed to high altitude”. Chest 131 (5): 1473–1478. doi:10.1378/chest.06-2235. PMID 17494796.

- ^ 渡邉興亞、国立極地研究所『南極大陸の氷を掘る! : ドームふじ深層掘削計画の立案から実施までの全記録』国立極地研究所〈極地選書, 2〉、2002年、104頁。ISBN 4-906651-04-6。

- ^ 三上俊夫「152.尿酸は運動ストレス時の抗酸化物質として作用する」『体力科學』第49巻第6号、日本体力医学会、2000年12月1日、NAID 110001949422。

- ^ 根岸、友恵、鈴木利典、濱武有子、藤原 大「酸化傷害に対する内在性防御物質としての尿酸の役割」研究期間2007年度〜2008年度(科学研究費助成事業データベース)

- ^ Smirnoff N (2001). “L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis”. Vitam Horm 61: 241 – 66. doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(01)61008-2. PMID 11153268.

- ^ Linster CL, Van Schaftingen E (2007). “Vitamin C. Biosynthesis, recycling and degradation in mammals”. FEBS J. 274 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05607.x. PMID 17222174.

- ^ a b Meister A (1994). “Glutathione-ascorbic acid antioxidant system in animals”. J Biol Chem 269 (13): 9397 – 400. PMID 8144521.

- ^ Wells W, Xu D, Yang Y, Rocque P (15 September 1990). “Mammalian thioltransferase (glutaredoxin) and protein disulfide isomerase have dehydroascorbate reductase activity”. J Biol Chem 265 (26): 15361 – 4. PMID 2394726.

- ^ Padayatty S, Katz A, Wang Y, Eck P, Kwon O, Lee J, Chen S, Corpe C, Dutta A, Dutta S, Levine M (1 February 2003). “Vitamin C as an antioxidant: evaluation of its role in disease prevention”. J Am Coll Nutr 22 (1): 18 – 35. PMID 12569111. オリジナルの2010年7月21日時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ 神林 康弘、人見 嘉哲、日比野 由利他「抗酸化物質(1)ビタミンC(アルコルビン酸)」『日本予防医学会雑誌』第3巻第2号、日本予防医学会、2008年、pp.3-12、ISSN 18814271、NAID 40016281331。

- ^ Shigeoka S, Ishikawa T, Tamoi M, Miyagawa Y, Takeda T, Yabuta Y, Yoshimura K (2002). “Regulation and function of ascorbate peroxidase isoenzymes”. J Exp Bot 53 (372): 1305 – 19. doi:10.1093/jexbot/53.372.1305. PMID 11997377.

- ^ Smirnoff N, Wheeler GL (2000). “Ascorbic acid in plants: biosynthesis and function”. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 35 (4): 291–314. doi:10.1080/10409230008984166. PMID 11005203.

- ^ Meister A (1988). “Glutathione metabolism and its selective modification” (PDF). J Biol Chem 263 (33): 17205 – 8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0508621102. PMID 3053703.

- ^ Fahey RC (2001). “Novel thiols of prokaryotes”. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55: 333–56. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.333. PMID 11544359.

- ^ Fairlamb AH, Cerami A (1992). “Metabolism and functions of trypanothione in the Kinetoplastida”. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 46: 695–729. doi:10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.003403. PMID 1444271.

- ^ Reiter RJ, Carneiro RC, Oh CS (1997). “Melatonin in relation to cellular antioxidative defense mechanisms”. Horm. Metab. Res. 29 (8): 363–72. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979057. PMID 9288572.

- ^ Tan DX, Manchester LC, Reiter RJ, Qi WB, Karbownik M, Calvo JR (2000). “Significance of melatonin in antioxidative defense system: reactions and products”. Biological signals and receptors 9 (3–4): 137–59. doi:10.1159/000014635. PMID 10899700.

- ^ 中村宜司「有機ゲルマニウム化合物Ge-132の生理作用に関する研究」岩手大学 博士論文 (農学)、甲第349号、2006年3月23日、NAID 500000348565、国立国会図書館書誌ID:000008361946。

- ^ 中村宜司、佐藤克行、秋葉光雄「胆汁色素代謝物ウロビリノーゲンの抗酸化作用」中村宜司 『日本農芸化学会誌』2001年3月5日、75巻、144ページ。抗酸化物質 - J-GLOBAL

- ^ NAKAMURA Takashi; SATO Katsuyuki; AKIBA Mitsuo; OHNISHI Masao (2006). “Urobilinogen, as a Bile Pigment Metabolite, Has an Antioxidant Function”. Journal of Oleo Science (日本油化学会) 55 (4): 191-197. doi:10.5650/jos.55.191. NAID 130000055572.

- ^ Baranano DE, Rao M, Ferris CD, Snyder SH (2002). “Biliverdin reductase: a major physiologic cytoprotectant”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (25): 16093–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.252626999. PMC 138570. PMID 12456881.

- ^ Liu Y, Li P, Lu J, Xiong W, Oger J, Tetzlaff W, Cynader M. (2008). “Bilirubin possesses powerful immunomodulatory activity and suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis”. J. Immunol. 181 (3): 1887–97. PMID 18641326.

- ^ a b Herrera E, Barbas C (2001). “Vitamin E: action, metabolism and perspectives”. J Physiol Biochem 57 (2): 43 – 56. doi:10.1007/BF03179812. PMID 11579997.

- ^ Packer L, Weber SU, Rimbach G (1 February 2001). “Molecular aspects of alpha-tocotrienol antioxidant action and cell signalling”. J. Nutr. 131 (2): 369S–73S. PMID 11160563.

- ^ a b Brigelius-Flohé R, Traber M (1 July 1999). “Vitamin E: function and metabolism”. FASEB J 13 (10): 1145 – 55. PMID 10385606.

- ^ Traber MG, Atkinson J (2007). “Vitamin E, antioxidant and nothing more”. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43 (1): 4–15. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.024. PMC 2040110. PMID 17561088.

- ^ 神林 康弘、人見 嘉哲、日比野 由利 他「抗酸化物質(2)ビタミンE」『日本予防医学会雑誌』第5巻第1号、日本予防医学会、2010年、pp.3-9、ISSN 18814271、NAID 40017134909。

- ^ 山内 亮「抗酸化ビタミンの脂質過酸化抑制機構」『食品・食品添加物研究誌』第215巻第1号、FFIジャーナル編集委員会、2010年、pp.17-23、ISSN 09199772、NAID 40017000566。

- ^ Wang X, Quinn P (1999). “Vitamin E and its function in membranes”. Prog Lipid Res 38 (4): 309 – 36. doi:10.1016/S0163-7827(99)00008-9. PMID 10793887.

- ^ Seiler A, Schneider M, Förster H, Roth S, Wirth EK, Culmsee C, Plesnila N, Kremmer E, Rådmark O, Wurst W, Bornkamm GW, Schweizer U, Conrad M (September 2008). “Glutathione peroxidase 4 senses and translates oxidative stress into 12/15-lipoxygenase dependent- and AIF-mediated cell death”. Cell Metab. 8 (3): 237–48. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.005. PMID 18762024.

- ^ Brigelius-Flohé R, Davies KJ (2007). “Is vitamin E an antioxidant, a regulator of signal transduction and gene expression, or a 'junk' food? Comments on the two accompanying papers: "Molecular mechanism of alpha-tocopherol action" by A. Azzi and "Vitamin E, antioxidant and nothing more" by M. Traber and J. Atkinson”. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43 (1): 2–3. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.016. PMID 17561087.

- ^ Atkinson J, Epand RF, Epand RM (2007). “Tocopherols and tocotrienols in membranes: A critical review”. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 44 (5): 739–764. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.11.010. PMID 18160049.

- ^ a b Azzi A (2007). “Molecular mechanism of alpha-tocopherol action”. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43 (1): 16–21. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.013. PMID 17561089.

- ^ Zingg JM, Azzi A (2004). “Non-antioxidant activities of vitamin E”. Curr. Med. Chem. 11 (9): 1113–33. PMID 15134510.

- ^ Sen C, Khanna S, Roy S (2006). “Tocotrienols: Vitamin E beyond tocopherols”. Life Sci 78 (18): 2088–98. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.001. PMC 1790869. PMID 16458936.

- ^ 矢澤 一良「ヘルスフード科学シリーズ(16)食品中の抗酸化物質(2)トコトリエノール」『食品と容器』第45巻第7号、缶詰技術研究会 / 缶詰技術研究会、2004年、pp.364-369、ISSN 09112278、NAID 40006319804。

- ^ カロチノイド [花色に関する実験 早川史乃 2001 千葉大学園芸学部・花卉園芸学研究室]

- ^ 武田弘志最近の話題116f ポリフェノール 『日本薬理学雑誌』116(3),2000年, p198 の日本薬理学による転載

- ^ 冨田裕一郎「アミノ・カルボニル反応生成物の抗酸化性に関する研究 : (第5報)トリプトファン・グルコース系反応生成物の抗酸化剤としての利用試験」『鹿児島大学農学部学術報告』第22巻、鹿児島大学、1972年3月、115-121頁、ISSN 04530845、NAID 110004993957。

- ^ a b 下橋淳子「褐変物質のDPPHラジカル消去能」『駒沢女子短期大学研究紀要』第37巻、駒沢女子短期大学、2004年、17-22頁、doi:10.18998/00000638、ISSN 02884844、NAID 110004678454。

- ^ 明治大学農学部農芸化学科食品機能科学研究室 研究の概要 Archived 2012年11月24日, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ 竹内徳男, 稲荷妙子, 森本仁美「味噌のDPPHラジカル捕捉能に関する研究」『岐阜女子大学紀要』第33号、岐阜女子大学、2004年、115-122頁、ISSN 02868644、NAID 110000146309、NDLJP:8558735。

- ^ a b 渡邊敦光、「お味噌の効能」『日本醸造協会誌』2010年 105巻 11号 p.714-723, doi:10.6013/jbrewsocjapan.105.714, 日本醸造協会

- ^ 市川朝子, 藤井聡, 河本正彦、「各種カラメル色素のリノール酸に対する抗酸化作用」『日本食品工業学会誌』 1975年 22巻 4号 p.159-163, doi:10.3136/nskkk1962.22.159, 日本食品科学工学会

- ^ Christen Y (1 February 2000). “Oxidative stress and Alzheimer disease”. Am J Clin Nutr 71 (2): 621S–629S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/71.2.621s. PMID 10681270.

- ^ Nunomura A, Castellani R, Zhu X, Moreira P, Perry G, Smith M (2006). “Involvement of oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease”. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 65 (7): 631–41. doi:10.1097/01.jnen.0000228136.58062.bf. PMID 16825950.

- ^ Wood-Kaczmar A, Gandhi S, Wood N (2006). “Understanding the molecular causes of Parkinson's disease”. Trends Mol Med 12 (11): 521–8. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.09.007. PMID 17027339.

- ^ Davì G, Falco A, Patrono C (2005). “Lipid peroxidation in diabetes mellitus”. Antioxid Redox Signal 7 (1–2): 256–68. doi:10.1089/ars.2005.7.256. PMID 15650413.

- ^ Giugliano D, Ceriello A, Paolisso G (1996). “Oxidative stress and diabetic vascular complications”. Diabetes Care 19 (3): 257–67. doi:10.2337/diacare.19.3.257. PMID 8742574.

- ^ Hitchon C, El-Gabalawy H (2004). “Oxidation in rheumatoid arthritis”. Arthritis Res Ther 6 (6): 265–78. doi:10.1186/ar1447. PMC 1064874. PMID 15535839.

- ^ Cookson M, Shaw P (1999). “Oxidative stress and motor neurone disease”. Brain Pathol 9 (1): 165–86. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00217.x. PMID 9989458.

- ^ 田中 芳明「臨床現場からの提言--酸化ストレスと抗酸化療法(第1回)酸化ストレスと抗酸化物質」『Food style 21』第13巻第1号、食品化学新聞社、2009年、pp.32-35、ISSN 13439502、NAID 40016423198。

- ^ 田中芳明「抗酸化物質」『外科と代謝・栄養』第43巻第6号、日本外科代謝栄養学会、2010年、pp.201-207、ISSN 03895564。

- ^ 駒形美穂, 伊藤雅子, 藤田薫他「生体内における酸化ストレスおよび抗酸化物質 (特集:酸化ストレス・抗酸化能評価)」『ジャパンフードサイエンス』第44巻第1号、日本食品出版 / 日本食品出版株式会社、2005年、pp.74-82、ISSN 03681122、NAID 40006571413。

- ^ Van Gaal L, Mertens I, De Block C (2006). “Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease”. Nature 444 (7121): 875–80. doi:10.1038/nature05487. PMID 17167476.

- ^ Aviram M (2000). “Review of human studies on oxidative damage and antioxidant protection related to cardiovascular diseases”. Free Radic Res 33 Suppl: S85–97. PMID 11191279.

- ^ 吉川 敏一、古倉 聡「フリーラジカルと癌予防 (癌の化学予防最前線)」『医学のあゆみ』第204巻第1号、医歯薬出版、2003年、pp.20-23、ISSN 00392359、NAID 40005609183。

- ^ Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, Giovannucci E, Colditz GA, Willett WC (1993). “Vitamin E consumption and the risk of coronary heart disease in men”. N Engl J Med 328 (20): 1450–6. doi:10.1056/NEJM199305203282004. PMID 8479464.

- ^ 大森 平野 玲子「食事因子と動脈硬化性疾患に関する研究」『日本栄養・食糧学会誌』第60巻第1号、日本栄養・食糧学会、2007年2月、3-9頁、doi:10.4327/jsnfs.60.3、ISSN 02873516、NAID 10026885268。

- ^ 葛谷恒彦, 松口貴子, 籾谷真奈, 北尾悟, 杉谷義憲「食品抗酸化物による血管内皮細胞障害防止効果の解析(1)血管内皮酸化障害モデルの作成」『大阪樟蔭女子大学学芸学部論集』第42巻、大阪樟蔭女子大学、2005年3月、97-105頁、NAID 110001138398。

- ^ Vivekananthan DP, Penn MS, Sapp SK, Hsu A, Topol EJ (2003). “Use of antioxidant vitamins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of randomised trials”. Lancet 361 (9374): 2017–23. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13637-9. PMID 12814711.

- ^ Sesso HD, Buring JE, Christen WG (November 2008). “Vitamins E and C in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: the Physicians' Health Study II randomized controlled trial”. JAMA 300 (18): 2123–33. doi:10.1001/jama.2008.600. PMC 2586922. PMID 18997197.

- ^ Lee IM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM (July 2005). “Vitamin E in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: the Women's Health Study: a randomized controlled trial”. JAMA 294 (1): 56–65. doi:10.1001/jama.294.1.56. PMID 15998891.

- ^ Roberts LJ, Oates JA, Linton MF (2007). “The relationship between dose of vitamin E and suppression of oxidative stress in humans”. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43 (10): 1388–93. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.06.019. PMC 2072864. PMID 17936185.

- ^ Bleys J, Miller E, Pastor-Barriuso R, Appel L, Guallar E (2006). “Vitamin-mineral supplementation and the progression of atherosclerosis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials”. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 84 (4): 880–7; quiz 954–5. doi:10.1093/ajcn/84.4.880. PMID 17023716.

- ^ Cook NR, Albert CM, Gaziano JM (2007). “A randomized factorial trial of vitamins C and E and beta carotene in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in women: results from the Women's Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study”. Arch. Intern. Med. 167 (15): 1610–8. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.15.1610. PMC 2034519. PMID 17698683.

- ^ Reiter R (1995). “Oxidative processes and antioxidative defense mechanisms in the aging brain”. FASEB J 9 (7): 526–33. doi:10.1096/fasebj.9.7.7737461. PMID 7737461.

- ^ Warner D, Sheng H, Batinić-Haberle I (2004). “Oxidants, antioxidants and the ischemic brain”. J Exp Biol 207 (Pt 18): 3221–31. doi:10.1242/jeb.01022. PMID 15299043.

- ^ Wilson J, Gelb A (2002). “Free radicals, antioxidants, and neurologic injury: possible relationship to cerebral protection by anesthetics”. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 14 (1): 66–79. doi:10.1097/00008506-200201000-00014. PMID 11773828.

- ^ Lees K, Davalos A, Davis S, Diener H, Grotta J, Lyden P, Shuaib A, Ashwood T, Hardemark H, Wasiewski W, Emeribe U, Zivin J (2006). “Additional outcomes and subgroup analyses of NXY-059 for acute ischemic stroke in the SAINT I trial”. Stroke 37 (12): 2970–8. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000249410.91473.44. PMID 17068304.

- ^ Lees K, Zivin J, Ashwood T, Davalos A, Davis S, Diener H, Grotta J, Lyden P, Shuaib A, Hårdemark H, Wasiewski W (2006). “NXY-059 for acute ischemic stroke”. N Engl J Med 354 (6): 588–600. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052980. PMID 16467546.

- ^ Yamaguchi T, Sano K, Takakura K, Saito I, Shinohara Y, Asano T, Yasuhara H (1 January 1998). “Ebselen in acute ischemic stroke: a placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Ebselen Study Group”. Stroke 29 (1): 12–7. doi:10.1161/01.STR.29.1.12. PMID 9445321.

- ^ Di Matteo V, Esposito E (2003). “Biochemical and therapeutic effects of antioxidants in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis”. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord 2 (2): 95–107. doi:10.2174/1568007033482959. PMID 12769802.

- ^ Rao A, Balachandran B (2002). “Role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in neurodegenerative diseases”. Nutr Neurosci 5 (5): 291–309. doi:10.1080/1028415021000033767. PMID 12385592.

- ^ Kopke RD, Jackson RL, Coleman JK, Liu J, Bielefeld EC, Balough BJ (2007). “NAC for noise: from the bench top to the clinic”. Hear. Res. 226 (1-2): 114–25. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2006.10.008. PMID 17184943.

- ^ 松下雪郎「生体の老化を抑制する食品」『化学と生物』第25巻第5号、日本農芸化学会、1987年、336-340頁、doi:10.1271/kagakutoseibutsu1962.25.336、ISSN 0453-073X、NAID 130003633212。

- ^ Thomas D (2004). “Vitamins in health and aging”. Clin Geriatr Med 20 (2): 259–74. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2004.02.001. PMID 15182881.

- ^ Ward J (1998). “Should antioxidant vitamins be routinely recommended for older people?”. Drugs Aging 12 (3): 169–75. doi:10.2165/00002512-199812030-00001. PMID 9534018.

- ^ 後藤 佐多良「抗酸化サプリメントの功罪とカロリー制限および運動の抗老化作用」『日本老年医学会雑誌』第45巻第2号、日本老年医学会、2008年、pp.155-158、doi:10.3143/geriatrics.45.155、ISSN 03009173、NAID 10021238780。

- ^ Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S (2006). “Molecular targets of dietary agents for prevention and therapy of cancer”. Biochem. Pharmacol. 71 (10): 1397–421. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2006.02.009. PMID 16563357.

- ^ Schulz TJ, Zarse K, Voigt A, Urban N, Birringer M, Ristow M (2007). “Glucose Restriction Extends Caenorhabditis elegans Life Span by Inducing Mitochondrial Respiration and Increasing Oxidative Stress”. Cell Metab. 6 (4): 280–93. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.011. PMID 17908557.

- ^ Barros MH, Bandy B, Tahara EB, Kowaltowski AJ (2004). “Higher respiratory activity decreases mitochondrial reactive oxygen release and increases life span in Saccharomyces cerevisiae”. J. Biol. Chem. 279 (48): 49883–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M408918200. PMID 15383542.

- ^ a b Sohal R, Mockett R, Orr W (2002). “Mechanisms of aging: an appraisal of the oxidative stress hypothesis”. Free Radic Biol Med 33 (5): 575–86. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00886-9. PMID 12208343.

- ^ a b Sohal R (2002). “Role of oxidative stress and protein oxidation in the aging process”. Free Radic Biol Med 33 (1): 37–44. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00856-0. PMID 12086680.

- ^ a b Rattan S (2006). “Theories of biological aging: genes, proteins, and free radicals”. Free Radic Res 40 (12): 1230–8. doi:10.1080/10715760600911303. PMID 17090411.

- ^ Green GA (December 2008). “Review: antioxidant supplements do not reduce all-cause mortality in primary or secondary prevention”. Evid Based Med 13 (6): 177. doi:10.1136/ebm.13.6.177. PMID 19043035.

- ^ 福地かつ美, 柳澤厚生「基礎講座 酸化ストレス(8)アンチエイジングと抗酸化食品」『アンチ・エイジング医学』第4巻第1号、メディカルレビュー社、2008年2月、75-78頁、ISSN 18801579、NAID 40015870825。 (

要購読契約)

要購読契約)

- ^ Duarte TL, Lunec J (2005). “Review: When is an antioxidant not an antioxidant? A review of novel actions and reactions of vitamin C”. Free Radic. Res. 39 (7): 671–86. doi:10.1080/10715760500104025. PMID 16036346.

- ^ a b Carr A, Frei B (1 June 1999). “Does vitamin C act as a pro-oxidant under physiological conditions?”. FASEB J. 13 (9): 1007–24. PMID 10336883.

- ^ Stohs SJ, Bagchi D (1995). “Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions”. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 18 (2): 321–36. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(94)00159-H. PMID 7744317.

- ^ Schneider C (2004). “Chemistry and biology of vitamin E”. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 49 (1): 7–30. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200400049. PMID 15580660.

- ^ Eiji Yamashita (2013). “Astaxanthin as a Medical Food”. Functional Foods in Health and Disease 3 (7): 255.

- ^ Hurrell R (1 September 2003). “Influence of vegetable protein sources on trace element and mineral bioavailability”. J Nutr 133 (9): 2973S–7S. PMID 12949395.

- ^ Hunt J (1 September 2003). “Bioavailability of iron, zinc, and other trace minerals from vegetarian diets”. Am J Clin Nutr 78 (3 Suppl): 633S–639S. PMID 12936958.

- ^ Gibson R, Perlas L, Hotz C (2006). “Improving the bioavailability of nutrients in plant foods at the household level”. Proc Nutr Soc 65 (2): 160–8. doi:10.1079/PNS2006489. PMID 16672077.

- ^ a b Mosha T, Gaga H, Pace R, Laswai H, Mtebe K (1995). “Effect of blanching on the content of antinutritional factors in selected vegetables”. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 47 (4): 361–7. doi:10.1007/BF01088275. PMID 8577655.

- ^ Sandberg A (2002). “Bioavailability of minerals in legumes”. Br J Nutr 88 (Suppl 3): S281–5. doi:10.1079/BJN/2002718. PMID 12498628.

- ^ a b Beecher G (1 October 2003). “Overview of dietary flavonoids: nomenclature, occurrence and intake”. J Nutr 133 (10): 3248S–3254S. PMID 14519822.

- ^ Prashar A, Locke I, Evans C (2006). “Cytotoxicity of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) oil and its major components to human skin cells”. Cell Prolif 39 (4): 241–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2184.2006.00384.x. PMID 16872360.

- ^ Hornig D, Vuilleumier J, Hartmann D (1980). “Absorption of large, single, oral intakes of ascorbic acid”. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 50 (3): 309–14. PMID 7429760.

- ^ Omenn G, Goodman G, Thornquist M, Balmes J, Cullen M, Glass A, Keogh J, Meyskens F, Valanis B, Williams J, Barnhart S, Cherniack M, Brodkin C, Hammar S (1996). “Risk factors for lung cancer and for intervention effects in CARET, the Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial”. J Natl Cancer Inst 88 (21): 1550–9. doi:10.1093/jnci/88.21.1550. PMID 8901853.

- ^ Albanes D (1 June 1999). “Beta-carotene and lung cancer: a case study”. Am J Clin Nutr 69 (6): 1345S–50S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/69.6.1345S. PMID 10359235.

- ^ a b Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud L, Simonetti R, Gluud C (2007). “Mortality in Randomized Trials of Antioxidant Supplements for Primary and Secondary Prevention: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis”. JAMA 297 (8): 842–57. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.842. PMID 17327526.

- ^ Study Citing Antioxidant Vitamin Risks Based On Flawed Methodology, Experts Argue News release from オレゴン州立大学 published on ScienceDaily, Accessed 19 April 2007

- ^ Bjelakovic, G; Nikolova, D; Gluud, LL; Simonetti, RG; Gluud, C (2008). “Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD007176. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007176. PMID 18425980.

- ^ Miller E, Pastor-Barriuso R, Dalal D, Riemersma R, Appel L, Guallar E (2005). “Meta-analysis: high-dosage vitamin E supplementation may increase all-cause mortality”. Ann Intern Med 142 (1): 37–46. PMID 15537682.

- ^ Bjelakovic G, Nagorni A, Nikolova D, Simonetti R, Bjelakovic M, Gluud C (2006). “Meta-analysis: antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention of colorectal adenoma”. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 24 (2): 281–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02970.x. PMID 16842454.

- ^ a b Hercberg S, Galan P, Preziosi P, Bertrais S, Mennen L, Malvy D, Roussel AM, Favier A, Briancon S (2004). “The SU.VI.MAX Study: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the health effects of antioxidant vitamins and minerals”. Arch Intern Med 164 (21): 2335–42. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.21.2335. PMID 15557412.

- ^ Caraballoso M, Sacristan M, Serra C, Bonfill X (2003). “Drugs for preventing lung cancer in healthy people”. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD002141. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002141. PMID 12804424.

- ^ Coulter I, Hardy M, Morton S, Hilton L, Tu W, Valentine D, Shekelle P (2006). “Antioxidants vitamin C and vitamin e for the prevention and treatment of cancer”. Journal of general internal medicine: official journal of the Society for Research and Education in Primary Care Internal Medicine 21 (7): 735–44. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00483.x. PMC 1924689. PMID 16808775.

- ^ a b c d Stanner SA, Hughes J, Kelly CN, Buttriss J (2004). “A review of the epidemiological evidence for the 'antioxidant hypothesis'”. Public Health Nutr 7 (3): 407–22. doi:10.1079/PHN2003543. PMID 15153272.

- ^ a b c Shenkin A (2006). “The key role of micronutrients”. Clin Nutr 25 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2005.11.006. PMID 16376462.

- ^ Radimer K, Bindewald B, Hughes J, Ervin B, Swanson C, Picciano M (2004). “Dietary supplement use by US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2000”. Am J Epidemiol 160 (4): 339–49. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh207. PMID 15286019.

- ^ Latruffe N, Delmas D, Jannin B, Cherkaoui Malki M, Passilly-Degrace P, Berlot JP (December 2002). “Molecular analysis on the chemopreventive properties of resveratrol, a plant polyphenol microcomponent”. Int. J. Mol. Med. 10 (6): 755–60. PMID 12430003.

- ^ Woodside J, McCall D, McGartland C, Young I (2005). “Micronutrients: dietary intake v. supplement use”. Proc Nutr Soc 64 (4): 543–53. doi:10.1079/PNS2005464. PMID 16313697.

- ^ a b c Hail N, Cortes M, Drake EN, Spallholz JE (July 2008). “Cancer chemoprevention: a radical perspective”. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45 (2): 97–110. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.004. PMID 18454943.

- ^ Williams RJ, Spencer JP, Rice-Evans C (April 2004). “Flavonoids: antioxidants or signalling molecules?”. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 36 (7): 838–49. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.01.001. PMID 15019969.

- ^ Virgili F, Marino M (November 2008). “Regulation of cellular signals from nutritional molecules: a specific role for phytochemicals, beyond antioxidant activity”. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 45 (9): 1205–16. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.001. PMID 18762244.

- ^ Valko M, Morris H, Cronin MT (2005). “Metals, toxicity and oxidative stress”. Curr. Med. Chem. 12 (10): 1161–208. doi:10.2174/0929867053764635. PMID 15892631.

- ^ Schneider C (2005). “Chemistry and biology of vitamin E”. Mol Nutr Food Res 49 (1): 7–30. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200400049. PMID 15580660.

- ^ Halliwell, B (2008). “Are polyphenols antioxidants or pro-oxidants? What do we learn from cell culture and in vivo studies?”. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 476 (2): 107–112. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2008.01.028. PMID 18284912.

- ^ World Cancer Research Fund and American Institute for Cancer Research (2007). Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Amer. Inst. for Cancer Research. ISBN 978-0972252225 日本語要旨:食べもの、栄養、運動とがん予防、世界がん研究基金と米国がん研究機構

- ^ Cherubini A, Vigna G, Zuliani G, Ruggiero C, Senin U, Fellin R (2005). “Role of antioxidants in atherosclerosis: epidemiological and clinical update”. Curr Pharm Des 11 (16): 2017–32. doi:10.2174/1381612054065783. PMID 15974956.

- ^ Lotito SB, Frei B (2006). “Consumption of flavonoid-rich foods and increased plasma antioxidant capacity in humans: cause, consequence, or epiphenomenon?”. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 41 (12): 1727–46. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.033. PMID 17157175.

- ^ Lemonick, M.D. (1999年7月19日). “Diet and cancer: can food fend off tumors?”. Times Inc.. 2009年10月20日閲覧。

- ^ “第5回 健康食品フォーラム報告書「健康食品の臨床利用と安全性」”. 財団法人医療経済研究・社会保険福祉協会. pp. 42. 2012年3月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2010年12月8日閲覧。

- ^ G. López-Lluch, N. Hunt, B. Jones, M. Zhu, H. Jamieson, S. Hilmer, M. V. Cascajo, J. Allard, D. K. Ingram, P. Navas, and R. de Cabo (2006). “Calorie restriction induces mitochondrial biogenesis and bioenergetic efficiency”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103 (6): 1768–1773. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510452103. PMC 1413655. PMID 16446459.

- ^ Larsen P (1993). “Aging and resistance to oxidative damage in Caenorhabditis elegans”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90 (19): 8905–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.19.8905. PMC 47469. PMID 8415630.

- ^ Helfand S, Rogina B (2003). “Genetics of aging in the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster”. Annu Rev Genet 37: 329–48. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.37.040103.095211. PMID 14616064.

- ^ Pérez, Viviana I.; Bokov, A; Van Remmen, H; Mele, J; Ran, Q; Ikeno, Y; Richardson, A (2009). “Is the oxidative stress theory of aging dead?”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 1790 (10): 1005–1014. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.06.003. PMC 2789432. PMID 19524016 2009年9月14日閲覧。.

- ^ Dekkers J, van Doornen L, Kemper H (1996). “The role of antioxidant vitamins and enzymes in the prevention of exercise-induced muscle damage”. Sports Med 21 (3): 213–38. doi:10.2165/00007256-199621030-00005. PMID 8776010.

- ^ Tiidus P (1998). “Radical species in inflammation and overtraining”. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 76 (5): 533–8. doi:10.1139/y98-047. PMID 9839079.

- ^ Ristow M, Zarse K, Oberbach A (May 2009). “Antioxidants prevent health-promoting effects of physical exercise in humans”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (21): 8665–70. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903485106. PMC 2680430. PMID 19433800.

- ^ Leeuwenburgh C, Fiebig R, Chandwaney R, Ji L (1994). “Aging and exercise training in skeletal muscle: responses of glutathione and antioxidant enzyme systems”. Am J Physiol 267 (2 Pt 2): R439–45. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.2.R439. PMID 8067452.

- ^ 角田聡, 水沼俊美, 坂井堅太郎「運動・スポーツにおける抗酸化物質の役割」『臨床スポーツ医学』第13巻、1996年11月、90-97頁、ISSN 02893339、NAID 10011118284。(

要購読契約)

要購読契約)

- ^ Leeuwenburgh C, Heinecke J (2001). “Oxidative stress and antioxidants in exercise”. Curr Med Chem 8 (7): 829–38. doi:10.2174/0929867013372896. PMID 11375753.

- ^ Takanami Y, Iwane H, Kawai Y, Shimomitsu T (2000). “Vitamin E supplementation and endurance exercise: are there benefits?”. Sports Med 29 (2): 73–83. doi:10.2165/00007256-200029020-00001. PMID 10701711.

- ^ Mastaloudis A, Traber M, Carstensen K, Widrick J (2006). “Antioxidants did not prevent muscle damage in response to an ultramarathon run”. Med Sci Sports Exerc 38 (1): 72–80. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000188579.36272.f6. PMID 16394956.

- ^ Peake J (2003). “Vitamin C: effects of exercise and requirements with training”. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 13 (2): 125–51. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.13.2.125. PMID 12945825.

- ^ Jakeman P, Maxwell S (1993). “Effect of antioxidant vitamin supplementation on muscle function after eccentric exercise”. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 67 (5): 426–30. doi:10.1007/BF00376459. PMID 8299614.

- ^ Close G, Ashton T, Cable T, Doran D, Holloway C, McArdle F, MacLaren D (2006). “Ascorbic acid supplementation does not attenuate post-exercise muscle soreness following muscle-damaging exercise but may delay the recovery process”. Br J Nutr 95 (5): 976–81. doi:10.1079/BJN20061732. PMID 16611389.

- ^ Schumacker P (2006). “Reactive oxygen species in cancer cells: Live by the sword, die by the sword”. Cancer Cell 10 (3): 175–6. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.015. PMID 16959608.

- ^ Seifried H, McDonald S, Anderson D, Greenwald P, Milner J (1 August 2003). “The antioxidant conundrum in cancer”. Cancer Res 63 (15): 4295–8. PMID 12907593.

- ^ Lawenda BD, Kelly KM, Ladas EJ, Sagar SM, Vickers A, Blumberg JB (June 2008). “Should supplemental antioxidant administration be avoided during chemotherapy and radiation therapy?”. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 100 (11): 773–83. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn148. PMID 18505970.

- ^ Block KI, Koch AC, Mead MN, Tothy PK, Newman RA, Gyllenhaal C (September 2008). “Impact of antioxidant supplementation on chemotherapeutic toxicity: a systematic review of the evidence from randomized controlled trials”. Int. J. Cancer 123 (6): 1227–39. doi:10.1002/ijc.23754. PMID 18623084.

- ^ Block KI, Koch AC, Mead MN, Tothy PK, Newman RA, Gyllenhaal C (August 2007). “Impact of antioxidant supplementation on chemotherapeutic efficacy: a systematic review of the evidence from randomized controlled trials”. Cancer Treat. Rev. 33 (5): 407–18. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.01.005. PMID 17367938.

- ^ Der Petkau-Effekt und unsere strahlende Zukunft (『ペトカウ効果と我らの晴れやかなる未来』)、1985年、ドイツ語

- ^ a b 肥田舜太郎・竹野内真理「福島原発事故のさなかに-本書の概略と意義-」(抜粋)、2011年6月9日、あけび書房『人間と環境への低レベル放射能の脅威 福島原発放射能汚染を考えるために』の序文

- ^ 肥田舜太郎,竹野内真理訳『人間と環境への低レベル放射能の脅威 福島原発放射能汚染を考えるために』あけび書房、2011年6月

- ^ ユーリ・バンダジェフスキー 著、久保田護 訳『放射性セシウムが人体に与える 医学的生物学的影響: チェルノブイリ・原発事故被曝の病理データ』合同出版、2011年12月13日、40頁。ISBN 978-4-7726-1047-6。

- ^ 青野要, 山本道夫, 飯田荘介, 内海耕慥「放射線障害におけるスーパーオキサイド生成系(O(2))とスーパーオキサイド・ディスムターゼ(SOD)及びビタミンEの関与に対する考察」『岡山医学会雑誌』第90巻第9-10号、岡山医学会、1978年、1297-1308頁、doi:10.4044/joma1947.90.9-10_1297、ISSN 0030-1558、NAID 130006858434。

- ^ 川野一之 ほか、「味噌の放射線防御作用並びにACF抑制作用を引き起こす有効成分の解析の試み」 味噌の科学と技術 51(12), 429-434, 2003-12, NAID 40006037256

- ^ “長崎原爆記”秋月辰一郎 著

- ^ 伊藤明弘「放射性物質を除去するみその効用」みそ健康づくり委員会『みそサイエンス最前線』1999年

- ^ 小原正之 ほか、「完熟味噌によるマウスの放射線防御作用」 味噌の科学と技術 50(1), 21-27, 2002-01, NAID 40003575952

- ^ 岡山理科大学 理学部 臨床生命科学科 食品予防医学研究室 岡山理科大学と札幌医科大学との共同研究とのこと

- ^ 石川洋哉, 松本清, 受田浩之「食品の抗酸化能評価法 (特集 食品抗酸化物質の評価と応用)」『食品・食品添加物研究誌』第215巻第1号、FFIジャーナル編集委員会、2010年、5-16頁、ISSN 09199772、NAID 40017000565。

- ^ 寺尾 純二「食品抗酸化物質の評価と応用」『食品・食品添加物研究誌』第215巻第1号、FFIジャーナル編集委員会、2010年、pp.1-5、ISSN 09199772、NAID 40017000563。

- ^ 江頭亨, 高山房子「フリーラジカルに酸化ストレス : ESRによる測定法を中心に」『日本薬理学雑誌』第120巻第4号、日本薬理学会、2002年10月、229-236頁、doi:10.1254/fpj.120.229、ISSN 00155691、NAID 10010332217。

- ^ Cao G, Alessio H, Cutler R (1993). “Oxygen-radical absorbance capacity assay for antioxidants”. Free Radic Biol Med 14 (3): 303–11. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(93)90027-R. PMID 8458588.

- ^ Ou B, Hampsch-Woodill M, Prior R (2001). “Development and validation of an improved oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay using fluorescein as the fluorescent probe”. J Agric Food Chem 49 (10): 4619–26. doi:10.1021/jf010586o. PMID 11599998.

- ^ EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (2010). “Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to various food(s)/food constituent(s) and protection of cells from premature aging, antioxidant activity, antioxidant content and antioxidant properties, and protection of DNA, proteins and lipids from oxidative damage pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/20061”. EFSA Journal 8 (2): 1489.

- ^ “Withdrawn: Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) of Selected Foods, Release 2 (2010)”. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service (2012年5月16日). 2012年6月13日閲覧。

- ^ USDA. “Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) of Selected Foods, Release 2 (2010)”. 2016年12月31日閲覧。

- ^ Prior R, Wu X, Schaich K (2005). “Standardized methods for the determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolics in foods and dietary supplements”. J Agric Food Chem 53 (10): 4290–302. doi:10.1021/jf0502698. PMID 15884874.

- ^ 三宅 義明「植物性抗酸化物質」『食品・食品添加物研究誌』第215巻第1号、FFIジャーナル編集委員会、2010年、pp.24-30、ISSN 09199772、NAID 40017000567。

- ^ 矢澤一良「ヘルスフード科学シリーズ(8)食品中の抗酸化物質」『食品と容器』第44巻第10号、缶詰技術研究会、2003年、552-558頁、ISSN 09112278、NAID 80016166408。

- ^ Xianquan S, Shi J, Kakuda Y, Yueming J (2005). “Stability of lycopene during food processing and storage”. J Med Food 8 (4): 413–22. doi:10.1089/jmf.2005.8.413. PMID 16379550.

- ^ Rodriguez-Amaya D (2003). “Food carotenoids: analysis, composition and alterations during storage and processing of foods”. Forum Nutr 56: 35–7. PMID 15806788.

- ^ Baublis A, Lu C, Clydesdale F, Decker E (1 June 2000). “Potential of wheat-based breakfast cereals as a source of dietary antioxidants”. J Am Coll Nutr 19 (3 Suppl): 308S–311S. doi:10.1080/07315724.2000.10718965. PMID 10875602.

- ^ Rietveld A, Wiseman S (1 October 2003). “Antioxidant effects of tea: evidence from human clinical trials”. J Nutr 133 (10): 3285S–3292S. doi:10.1093/jn/133.10.3285S. PMID 14519827.

- ^ Maiani G, Periago Castón MJ, Catasta G (November 2008). “Carotenoids: Actual knowledge on food sources, intakes, stability and bioavailability and their protective role in humans”. Mol Nutr Food Res 53: NA. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200800053. PMID 19035552.

- ^ Henry C, Heppell N (2002). “Nutritional losses and gains during processing: future problems and issues”. Proc Nutr Soc 61 (1): 145–8. doi:10.1079/PNS2001142. PMID 12002789.

- ^ “Antioxidants and Cancer Prevention: Fact Sheet”. National Cancer Institute. 2007年2月27日閲覧。

- ^ Ortega RM (2006). “Importance of functional foods in the Mediterranean diet”. Public Health Nutr 9 (8A): 1136–40. doi:10.1017/S1368980007668530. PMID 17378953.

- ^ Goodrow EF, Wilson TA, Houde SC (October 2006). “Consumption of one egg per day increases serum lutein and zeaxanthin concentrations in older adults without altering serum lipid and lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations”. J. Nutr. 136 (10): 2519–24. doi:10.1093/jn/136.10.2519. PMID 16988120.

- ^ Witschi A, Reddy S, Stofer B, Lauterburg B (1992). “The systemic availability of oral glutathione”. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 43 (6): 667–9. doi:10.1007/BF02284971. PMID 1362956.

- ^ Flagg EW, Coates RJ, Eley JW (1994). “Dietary glutathione intake in humans and the relationship between intake and plasma total glutathione level”. Nutr Cancer 21 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1080/01635589409514302. PMID 8183721.

- ^ a b Dodd S, Dean O, Copolov DL, Malhi GS, Berk M (December 2008). “N-acetylcysteine for antioxidant therapy: pharmacology and clinical utility”. Expert Opin Biol Ther 8 (12): 1955–62. doi:10.1517/14728220802517901. PMID 18990082.

- ^ van de Poll MC, Dejong CH, Soeters PB (June 2006). “Adequate range for sulfur-containing amino acids and biomarkers for their excess: lessons from enteral and parenteral nutrition”. J. Nutr. 136 (6 Suppl): 1694S–1700S. PMID 16702341.

- ^ Wu G, Fang YZ, Yang S, Lupton JR, Turner ND (March 2004). “Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health”. J. Nutr. 134 (3): 489–92. PMID 14988435.

- ^ Pan MH, Ho CT (November 2008). “Chemopreventive effects of natural dietary compounds on cancer development”. Chem Soc Rev 37 (11): 2558–74. doi:10.1039/b801558a. PMID 18949126.

- ^ a b 石沢信人, 杉田収, 斎藤秀晃, 中野正春「ワインと各種飲料物の抗酸化能」『新潟県立看護短期大学紀要』第3巻、新潟県立看護短期大学紀要委員会、1997年12月、3-8頁、ISSN 13428454、NAID 110007525074。

- ^ Kader A, Zagory D, Kerbel E (1989). “Modified atmosphere packaging of fruits and vegetables”. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 28 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1080/10408398909527490. PMID 2647417.

- ^ Zallen E, Hitchcock M, Goertz G (1975). “Chilled food systems. Effects of chilled holding on quality of beef loaves”. J Am Diet Assoc 67 (6): 552–7. PMID 1184900.

- ^ Iverson F (1995). “Phenolic antioxidants: Health Protection Branch studies on butylated hydroxyanisole”. Cancer Lett 93 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1016/0304-3835(95)03787-W. PMID 7600543.

- ^ “E number index”. UK food guide. 2007年3月5日閲覧。

- ^ Robards K, Kerr A, Patsalides E (1988). “Rancidity and its measurement in edible oils and snack foods. A review”. Analyst 113 (2): 213–24. doi:10.1039/an9881300213. PMID 3288002.

- ^ 吉川春寿 & 芦田淳 1995, p. 267「抗酸化剤」

- ^ Del Carlo M, Sacchetti G, Di Mattia C, Compagnone D, Mastrocola D, Liberatore L, Cichelli A (2004). “Contribution of the phenolic fraction to the antioxidant activity and oxidative stability of olive oil”. J Agric Food Chem 52 (13): 4072–9. doi:10.1021/jf049806z. PMID 15212450.

- ^ CE Boozer, GS Hammond, CE Hamilton (1955) "Air Oxidation of Hydrocarbons. The Stoichiometry and Fate of Inhibitors in Benzene and Chlorobenzene". Journal of the American Chemical Society, 3233–3235

- ^ “Market Study: Antioxidants”. Ceresana Research. 2008年12月5日閲覧。

- ^ “Why use Antioxidants?”. SpecialChem Adhesives. 2007年2月27日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Fuel antioxidants”. Innospec Chemicals. 2006年10月15日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2007年2月27日閲覧。

- ^ “老化はなぜ進むか、「酸化ストレス」と「解糖系」が"老化研究のカギ" WISMERLL NEWS Vol.30 Mar.2010”. ウイスマー研究所/株式会社ウイスマー. 2011年2月3日閲覧。

- ^ “酸素スーパーオキシドジスムターゼ (SOD) の活性測定法,Dojin News No.096/2000”. 同人化学. 2011年2月3日閲覧。

抗酸化物質と同じ種類の言葉

- 抗酸化物質のページへのリンク