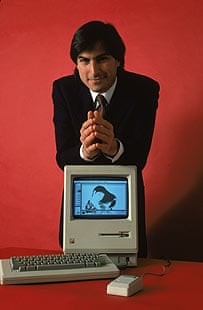

Even by Apple's standards, the past few weeks have been turbulent. The company delivered its final address, after 24 years, to the crowd at the annual Macworld conference, and then faced the news that co-founder and chief executive Steve Jobs was being forced to take a leave of absence for health reasons. Earlier this week it announced record-breaking sales and profits – even as technology giants such as Microsoft, Intel and Sony announced jobs cuts or losses.

Yet even these dramatic events pale into insignificance in comparison to what happened at Apple a quarter of a century ago, when it launched what many believe was the product that changed the face of the computer industry: the Macintosh.

Twenty-five years ago, on 22 January 1984, the Mac famously launched with a $1.5m, 30-second commercial run during American TV's biggest event, the Super Bowl. More than 90 million people were watching when Apple unveiled the brand that, even after all these years, is still at the core of the company's identity.

In a world dominated by computers where a mouse and "windows" are commonplace, it's easy to forget what PCs were like in 1984. The best-selling ones, including the $5,000 IBM PC XT, $600 Commodore 64 and Apple's own $1,200 Apple II, offered black screens and typewriter-like lines of green or white letters; to copy a file you typed obscure lines like "copy a:\autoexec.bat c:\windows". Mistakes – sometimes disastrous ones – were common. And typewriters, of course, don't need a mouse.

The Macintosh, priced between $1,995 and $2,495, aimed to change all that by introducing an affordable machine using the window-and-mouse system Jobs had seen on a visit to Xerox, which had an early version of the system. "It was obvious that every computer in the world would work this way someday," Jobs said later.

But how to tell people of the dramatic change it would offer? Not for Jobs a standard advert showing the machine. Instead, in the science fiction spot – overseen by Blade Runner director Ridley Scott – a legion of worker drones are lectured by a huge, Big Brother-like entity representing IBM and the existing computer companies.

Into the picture runs a young woman, symbolising Apple, who is chased by armed police before smashing the screen and freeing the enslaved masses. An ominous, movie-trailer voice then intones: "On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you'll see why 1984 won't be like '1984'."

The ad has since been hailed as one of the greatest ever because of its audacious approach and immediate impact. But it also reflected, in part, the optimism and – even hubris – of the young millionaires in charge of the company. Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak remembers the first time he saw the commercial.

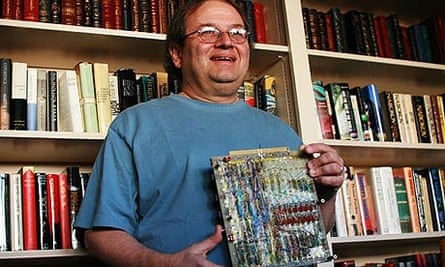

"[Jobs] sat me down in front of a U-Matic tape machine and played the 1984 ad, one time," he told the Guardian in an interview last week. "I was stunned. I was a bit naïve – I thought it was incredible science fiction. It was very rebellious in a sense. I said 'Wow, we're going to show this at the Super Bowl? This is the best ad I've ever seen.'"

According to Wozniak, Jobs said the company's board had decided against showing the spot because of the $800,000 price for a Super Bowl premiere – almost leading Wozniak to dip into his own pockets, even though cost wasn't the real reason they'd gone cold on it.

"I didn't realise the board had turned it down because they were shaky about coming out against Big Blue… I thought it was the money," he says. "I thought about it and thought about it. Steve and I were pretty wealthy by then, so I said 'I'll pay half if you pay the other half… this thing should be shown – this is us.'"

In the end, however, it was approved – and seen by an estimated 97 million people. The Mac was born. Though even by then the project had been running for nearly five years.

It was the brainchild of Jef Raskin, a computer scientist from New York who had joined Apple in 1978 and believed that computers needed to be easier to use.

After seeing the futuristic computer systems used at Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center – which used graphics instead of text input, and used a mouse as well as a keyboard – Raskin decided that it was the only way to successfully sell computers to millions of people.

As Raskin and others developed the idea of computers with a WIMP (windows, icons, mouse, pointer) interface, the team slowly coalesced, bringing together people from across the company, with a group including hardware engineer Burrell Smith, and programmers Bud Tribble and Bill Atkinson.

Andy Hertzfeld, who joined the Mac team in early 1981, ended up acting as a bridge between Atkinson and Smith as one of the main developers behind the core system software. He remembers the group's reputation and how he started gravitating towards them.

"When this little rebellious skunkworks Macintosh project started up… well, I was friends with the guy he picked to be the hardware designer, Burrell Smith. And so I just started helping Burrell out."

Wozniak also joined the team around the same time, drawn by the enthusiasm and ingenuity of the people working on the Mac.

"I like crazy, eccentric people," he says. "I like people that have brilliant artistic minds; people who think for themselves and contradict the established reality. All those people somehow, the ones who couldn't get a job elsewhere in Apple, who couldn't satisfy a manager very well, were all grabbed by Jef Raskin on this Macintosh project."

In the early days, Jobs saw the Mac as an unwelcome diversion and potential competition for his own project, the high-end Lisa computer (named after his first child). The Lisa was also based on a graphical interface – but following a series of clashes with his own team, Jobs found a home with the Macintosh group.

"They didn't like Steve's personality," says Wozniak. "Steve would have a vision and they would fight it – they would have a different vision of their own. They just got tired of Steve calling them idiots."

Jobs took part of Raskin's vision of a low-cost, usable machine and moulded it into his own image. Early prototypes included surprising little additions – such as a screen-flipping switch so that people could use a traditional green-on-black monitors instead of the Mac's black-on-white screen. But the extras were knocked back as Jobs stripped things down and helped guide things towards a finished product.

"We thought we were going to change the world," says Hertzfeld, who has gathered together stories of the Mac's development on the website Folklore.org and in the book Revolution in the Valley. "One of Steve Jobs's roles was to keep drumming into us how important what we were doing was going to be to everyone. We really believed it.

"It was very exciting, but it was also a lot of pressure. There was a funny tension between having a blast – we liked each other and we loved what we were doing – but at the same time there was enormous pressure to do it quicker than we could. When I started on the project, we were supposed to ship it in 10 months. It ended up taking more like 36 months."

Despite the excitement inside the Macintosh division, to the rest of the company it remained an unloved splinter group. The Apple II continued to be phenomenally popular and the basis for all of Apple's success – indeed, it continued production until 1993 – and the $10,000 Lisa was seen as the machine of the future.

"The Mac was kind of a funny hybrid between the two, and no one thought much of it," he says. "Even after Steve Jobs took it over, a lot of people thought it was the Steve Jobs back-to-the-garage fantasy, that he was trying to pull Apple back to its roots with a small team who were very excited about what they were doing."

Attitudes shifted quickly, however, thanks to mistakes elsewhere in the company. When the $10,000 Lisa failed to make an impact on its release in 1983, eyes began turning to Macintosh as a serious prospect.

"People started investing their hopes in the Macintosh," says Hertzfeld, who now works for Google. "By the time the Mac shipped, it was kind of 'bet the company': it was clearly the most important thing at the company."

Dag Spicer, senior curator at the Computer History Museum in Palo Alto, California, says it was a radical departure to have a graphic representation of what was stored on the computer – rather than be forced to use the typewriter-like "command line" to instruct the machine about what to do.

"[Until then] you had to know what all these incantations and secret words were," he explains. "The big difference with the Mac was that a complete novice – indeed children – 10-year-olds, five-year-olds who had never seen a computer before, seemed to instantly and intuitively lunge for the mouse."

Hertzfeld remembers the moment in more graphic terms. "It was like an orgasm," he says. "A release of all that hard work for three years, finally unveiling it to the world. That just felt fantastic… that was the culmination."

On the back of its enormous exposure and marketing campaign, the Mac made big splash. Early sales were strong, but after a few months just 50,000 of the machines had been snapped up.

Faced with another problematic product launch after the problems with the Lisa, Apple's chief executive John Sculley – who had been lured away from Pepsi by Jobs, but was finding working alongside him increasingly difficult – decided to pump more resources into keeping the Mac afloat.

Over the coming years, the Mac secured itself in the market, thanks to the burgeoning desktop publishing industry. It also spawned competitors: Microsoft launched the first version of Windows in 1985, having licensed some aspects of the interface from Apple. But as Windows became more capable, Apple filed a lawsuit, claiming in 1988 claimed that Windows copied the "look and feel" of the Mac. The suit failed, and graphical interfaces became the norm for modern computers in homes and offices around the world.

In fact, says Hertzfeld, the influence of the ideas behind the Macintosh is so strong that it may have even hampered other developments.

"It's just amazing that a computer I can buy for a lot cheaper than the original Mac is literally 100,000 times more powerful," he says. "[But] the software is where I think there's either a lack of imagination or a difficulty in changing paradigms. It hasn't moved significantly past the paradigms we set 25 years ago."

The reasons are many and complex, ranging from the sheer scale – and hence inertia – of the PC industry, to Microsoft's dominance. But without the Macintosh, says Wozniak, things would certainly not have been the same.

"I don't think we would [be in the same place], but I don't know what place we would be in," he says. "We certainly converted the world over to the mouse. I like to say that every computer in the world is now a Macintosh."

Spicer agrees. Even if inventors like Douglas Engelbart, who devised the first computer mouse, and teams like Xerox PARC had made great strides in creating the new ideas for how to use a computer, the Mac deserves a place in history as the machine that popularised such technologies.

"I think the credit deservedly goes to the person or the entity that brings it to the masses," he says. "Apple is the one that brought it to the world. You really have to give them a lot of credit."

In retrospect, Wozniak believes there is an analogy with the car industry – and that while his own Apple II was an integral part of the PC revolution, it will be the Macintosh that goes down as the machine that changed the way we think about computers.

"I think the first Macintosh was like the Model T Ford – even 25 years later, you can see the resemblance to it," he says.

"Sure, one is a little bit cruder and simpler… but 20 years from now, we'll look at a Macintosh and pretty much understand the similarities."