And still, the Beatles. Will we ever get over them? However many remasterings of the records there are, however many dramas, documentaries and memoirs of their life and times, it seems there will always be room for something more. The flood of material about the band will never slacken, because our appetite for it will never be sated.

I fell ravenously on In Their Lives, even if I did balk at the subtitle “Great Writers on Great Beatles Songs”. While nearly all of the 28 essays here feature great Beatles songs (let’s draw the line at “Yellow Submarine” and “Octopus’s Garden”) it’s a bit presumptuous to claim greatness for the other half of the equation. Charmed as I am by David Duchovny (“Dear Prudence”) I’m not sure he’s even a great actor, let alone a great writer. And Francine Prose (“Here Comes the Sun”) really lets the side down by including her nine-year-old granddaughter as co-author (“we’re all delighted that Emilia likes the Fab Four”). A few others here are too eager to share their generational bonding over the Beatles, though I did like the moment Ben Zimmer asked his son where he would look if he wanted to parse the lyrics of “I Am the Walrus”. His reply: “Goo goo ga Google”. Lennon would have laughed.

Editor Andrew Blauner perhaps encouraged this “me first” angle when he was rounding up his contributors. Several novelists – Jane Smiley, Joseph O’Neill, Mona Simpson, Elissa Schappell – choose a song essentially as a springboard to reminiscence. Rebecca Mead discusses “Eleanor Rigby” as the associative memory-link with the divorcing parents of a childhood friend, and so to the realisation that adults weren’t just there to provide “the untroubled backdrop to the dramas of children”. It’s nicely written, but its relevance is tenuous. The collection can be roughly divided between two types of essay: “What the Beatles meant to me”, and “Why the Beatles’s songs were great”. I much prefer the second type, because they are specific and analytical, whereas the my-life-was-never-the-same-again riff might have been triggered by any sort of musical madeleine.

The very best essays, of course, can do both. I loved Peter Blauner’s likening the first-note propulsion of “And Your Bird Can Sing” to a jet taking off, “firing on all cylinders”. He proceeds to examine precisely why it works, addressing the great and mysterious alchemy that transformed an unpromising demo one week into a two-minute masterpiece the next: “The foundation is still John’s on the final version, but it’s Paul joining George on the harmony guitar intro, giving a necessary touch of raw urgency to the part that Harrison had just played prettily the week before … He trims his vocal part, giving John enough room to state his case while chiming in strategically for just a few words at the end of each verse. And then he lays down that monster bass line, which Marshall Crenshaw compares to the crucial element in a Bach invention, the unnoticed piece that locks everything into place”. And there he might have left it, but instead he supplies a lovely coda about not visiting the Lennon memorial in Central Park for years, because “the real spirit of the man exists in a more private place. And I go there whenever I hear this glorious ode to being misunderstood”.

In essence the Beatles combined the catchiness of Tin Pan Alley songwriting with the raucousness and energy of rock’n’roll – and that was just the first half of their career. As Malcolm Gladwell once pointed out, they had 10,000 hours of live performance behind them before they even discovered what they could do in a studio. In the words of Jon Pareles, “they were pros who refused to become hacks”. Some kind of restlessness was goading them on, underpinned by an individual virtuosity that gave them the confidence to experiment. And as the music becomes more sui generis so the pronouncements on it become increasingly sonorous.

“Tomorrow Never Knows”, Pareles says, was “a portal to decades of music to come”. Alec Wilkinson reckons that “She Said She Said” describes “circumstances novel to western awareness and has no obvious antecedent or reference”. Adam Gopnik tops them both in arguing that the “Strawberry Fields Forever”/“Penny Lane” single was the most significant work of art in the 1960s, “the one that articulated the era’s hopes for a crossover of pop art and high intricacy” – for a little while “such music suggested that anything was possible”. They are not necessarily wrong, any of them.

Others reach for literature as a means of exaltation. Nicholas Dawidoff in a brilliant essay describes “A Day in the Life” as “Ulysses in a pop song, the typical day made unforgettable”, and “In My Life” as “rock’s analog to Sonnet 116”. O’Neill recalls the more fanciful musings of Christopher Ricks on Bob Dylan when he likens “Good Day Sunshine” to a poem by John Donne, yet I found it hard to resist the song’s “cunningly suspenseful” bass opening compared to “a discus thrower’s windup”.

Certain contributions are plain cuckoo. Chuck Klosterman seems as confused as anyone else by his choice of “Helter Skelter” – “(maybe) the sixth-best song on their fifth-best album” and “the well-considered, capably executed, fully conscious manifestation of a bad idea”. But it’s perverse fun at least. I couldn’t understand why Pico Iyer writes about “Yesterday”, given his admission that the Beatles “have never been a group I’ve enjoyed”. Was he that desperate to accept the commission?

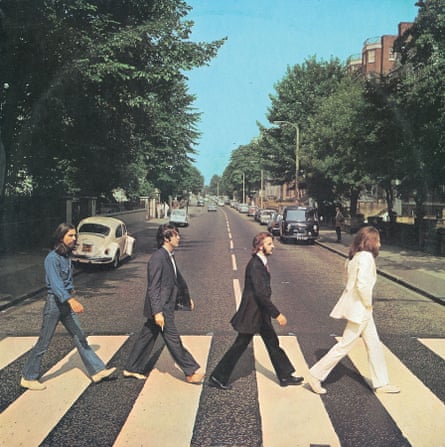

Books such as this have to be measured against Ian MacDonald’s peerless Revolution in the Head, not only the best ever book about the Beatles but probably the best ever book about rock music in general. He brought a musicologist’s erudition, a historian’s deep insight and a fan’s enthusiasm to the task of explaining why the band matters so much; it’s a book I consult on an almost daily basis. Only once, perhaps, does In Their Lives approach his greatness, when Rick Moody’s essay somehow melds the end of his parents’ marriage to the “The End” medley from Abbey Road. Composed in the last gasp of the 1960s, the medley marks what he sees as the band’s last hurrah, a togetherness in the midst of so much recrimination and mistrust, expressed in “the infamous Paul-George-John guitar showdown at the end of a long and winding career”. Moody nails it beautifully, right down to Harrison’s closing solo.

As a fan who knew the streets they walked and the pubs they drank in, I used to believe the Beatles “belonged” to Liverpool. Time has told me otherwise. John, Paul, George and Ringo of course belong to us all, “their apostolic names” (Moody) bandied around as if they were our own familiars. Most pop music withers in memory. They can’t be the same songs they were, because we aren’t the same people. But Beatles songs may grow old with you. Or as Shawn Colvin (“I’ll Be Back”) puts it: “I loved it when I heard it in 1965. I still do and I always will.”

Anthony Quinn’s most recent novel, Eureka, is published by Jonathan Cape.

In Their Lives: Great Writers on Great Beatles Songs is published by Blue Rider. To order a copy for £16.99 (RRP £19.99) go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion