This is the most difficult post I’ve written, not because the sources were difficult to locate (they were), but because the topics are painful and sensitive. I’ll cut to the chase: this post discusses murder, rape, and racism, three topics that, when handled poorly, can be offensive to many readers. With that in mind, please give me the benefit of the doubt when you read the following.

Intro

This topic came to my attention during research for a previous post: The “Oh, Mistake” incident, and crime in apres-guerre Japan 「オー・ミステーク」事件と「アプレゲール犯罪」. Japanese Wikipedia has an entry titled 小倉黒人米兵集団脱走事件 (Kokura black American soldier group breakout), referring to an AWOL incident in July, 1950. The event was fictionalized by Seichō Matsumoto 松本清張 in his short story 『黒地の絵』 Kuroji no e “Painting on a Black Canvas”, published in a collection of stories in 1965. I made note of the incident and moved on to other topics.

Explaining the motivation for writing a particular post is complicated. Sometimes it’s based on my interests, e.g. my post about interesting train lines in Tokyo (explanation: I love trains). Sometimes it’s based on my wanting to solve a riddle, like the identity of a balloon-man or the location of an architecturally significant house. And sometimes it’s a combination of factors.

Why am I writing this preamble? It’s because this post discusses two incidents involving rape and murder committed by American soldiers in Japan in 1950. News from this era was highly censored, so primary sources are limited. Furthermore, the soldiers involved were black Americans, so the available sources tend to approach the topic through the lense of race;

What are my motivations? I’m writing about this topic because I find it interesting; it’s a historical mystery (what actually happened?) involving a prominent author whose film adaptions I enjoy (Seicho Matsumoto), and the incident illustrates the importance if the written word. Were it not for Matsumoto’s fictional story, we would not be talking about these likely that nobody would be aware of the actual events.

(I) Just the facts

This post is actually about two events that occurred one week apart in July, 1950, the ‘Murder on the 4th of July’ and the ‘Kokura Incident’, which I address in chronological order:

1. Murder on the 4th of July

In the early morning of July 4, 1950, James L. Clark, an American soldier, murdered a Japanese family in Kokura city, Kyushu (the daughter survived). The following article from the St. Petersburg Times on September 3, 1950 is one of the only references available online. Given the nature of press censorship at the time, it is somewhat surprising that this event was made public. However, it’s possible that this death sentence was selectively made public to project an image of law-and-order.

2. The Kokura riot of July 11th

The second event is the incident that Matsumoto wrote about in his book, the so-called “black American soldier break-out”, during which a large group of soldiers, all of whom were black, left Camp Jono without permission for a final “night on the town” before being shipped to Korea the following day.

First, some context: The Korean War began on June 25, 1950 when North Korea invaded South Korea. The United States reacted, mobilizing thousands of troops to Japan’s southern island of Kyushu, close to the Korean peninsula. Many of these troops passed through the northern tip of Kyushu, which included Camp Jono in the city of Kokura 小倉市, now the central part of Kitakyushu City 北九州市 (Kokura Station 小倉駅 is the city’s main station; just north of Kokura was Moji port/Moji city.)

The most succinct account of the riot is written by Tessa Morris-Suzuki in her essay, “Lavish are the Dead: Re-envisioning Japan’s Korean War 死者の奢り あらためて日本の朝鮮戦争を思い浮かべる“. She notes that the mobilization of troops to Kyushu was not smooth, a contributing factor leading up to the riot:

“The departure of the 24th Infantry Regiment to Korea was chaotic…there was inadequate accommodation to house them. From there, as they discovered, they were to be shipped to Korea in a hastily assembled flotilla of ‘fishing boats, fertilizer haulers, coal carriers and tankers’. It was against the background of this chaos, as the miseries of their situation and the prospect of impending death confronted the soldiers, that the mass breakout and riot occurred.”

She continues:

“The ‘mass escape’ in question took place soon after the start of the war, on 11 July 1950, when some 200 soldiers from the US 24th Infantry Regiment, on their way to the Korean War front, staged a breakout from Camp Jōno, and descended on the centre of Kokura, smashing shop windows, assaulting women and engaging in fights with local people. One Japanese man was shot dead in the riot, several were injured and, according to the recollections of the then mayor of Kokura, Hamada Ryōsuke, about 28 women were raped.“

She cites an interview with mayor Hamada Ryōsuke in ‘Chōsen sensō shitai shorihan’ (pp. 174-75) and references Black Soldier, White Army: The 24th Infantry Regiment in Korea, which is the most comprehensive English account of the events. In Black Soldier, White Army, the incident is described as resulting from the confusion of the troop movements and, perhaps too generously describes the AWOL/’rioting’ soldiers as deciding to “slip away for one last evening in town”. According to some sources, the number of soldiers involved in the riots was as many as 200 or 250; Black Soldier, White Army provides support for a slightly smaller number, noting that 75 men were reported as having been detained by other members of the military, and the Japanese police lodged a complaint, estimating the number of “black deserters” at 100 (page 80).

According to sources cited by Black Soldier, White Army, the behavior of the men included fighting, beating up civilians, and attempting rape. The book also notes that the soldiers “shot the town up” and that the soldiers “responded with gunfire when military police arrived”. The following passages provide a good summary of the incident:

Other accounts provide more specific details. Media, Propaganda and Politics in 20th-Century Japan notes that “Testimony revealed in the 1975 Fukuoka Prefectural edition of the Asahi suggests that some women were sexually assaulted in front of their husbands.” The most specific accounts come from an article written in 2012 by Kashima Takumi 加島 巧. Although written in Japanese, Kashima’s essay quotes materials that were written in English; it also includes several maps and a chronology of the events. Among the English sources, he cites a report dated July 17, 1950, addressed to the US military police:

“To: Chief of Kyushu Civil Affairs Region Provost Marshal, Fukuoka Area

SUBJECTS: MASS VIOLENCE COMMITTED BY NEGRO OCCUPATIONARIES

Moji port has been busy with the continuous landing of occupation personnel and war supplies while a steady stream of servicemen is flowing into Moji city from Kokura to join the unit waiting further orders at the said port. The said servicemen are often seen walking around the streets and cases of violent act, rape, intimidation and robbery committed by them have been reported.”

Following this passage are reports of four illegal acts taking place on the night of July 10, 1950, including “Illegal entry”, “Unlawful act”, “Attempted rape”, and “Robbery committed by Occupation personnel”.

In addition to these historical accounts, there is also Matsumoto’s fictionalized 『黒地の絵』 Kuroji no e, which cleaves close-enough to the known facts of the Kokura incident that it can be confused with the real-life events. Matsumoto’s story is described in detail in The American Occupation of Japan and Okinawa: Literature and Memory (pp. 86-97). In Matsumoto’s story, a group of black soldiers escapes from Camp Jono on the night of July 11 or 12, 1950; they are recent arrivals to the Kokura region, soon to be shipped off to the Korean war. The soldiers in the story mistake a family’s house for a bar, demanding beer, and referring to the wife as “Mama-san”. After growing increasingly drunk, the soldiers rape the wife in the presence of the husband. See the following:

The details correspond quite closely to reported “facts” of the real event; for example, the arrival of troops to the Kokura area with imminent departure to Korea war is mentioned in various sources. The date of the break-out is virtually identical. Sources report the riot starting on the evening of July 10th, 1950, spilling into July 11th (source: Kashima, see footnotes), as opposed to July 11 or 12 per Matsumoto’s story. Further similarities include testimony from 1975 interviews in the Fukuoka Prefectural edition of the Asahi, which noted that soldiers, with stolen alcohol, entered homes looking for women, asking “Hey mama-san, are there any girls in here?”. They were reported as having committed rape of a woman in front of her husband (as noted by Media, Propaganda and Politics in 20th-Century Japan). Or were they influenced by Matsumoto’s published story?

Note: an English translation of Matsumoto’s book was written by Takumi Kashima, author of the aforementioned essay. The translation is titled: Tattoo on the black soldier’s breast = 黒地の絵 : it’s only me that remembers it.: English translation of Matsumoto Seicho’s Kuroji no e (2011)

(II) Why ‘just the facts’ is difficult

Because of the nature and scale of the events at Kokura, I had assumed there would be a reasonably large footprint on the English-language internet. However, there is a surprisingly short trail of information about these events, even in Japanese. Even some of the existing resources are unhelpful. For example, the “Chronology, Japan, 1945-1960” chapter of the exhaustive Relations between Allied Forces and the Population of Japan, blandly describes the event as follows:

“Jul. 11, 1950: A group of US soldiers attacked several houses in the town of Ogura committing acts of violence and robberies (Haikyo Vol. 9, p. 82 communicated by Eddy Dufourmont).” [Ogura is an alternate reading of 小倉, which I translate as Kokura.]

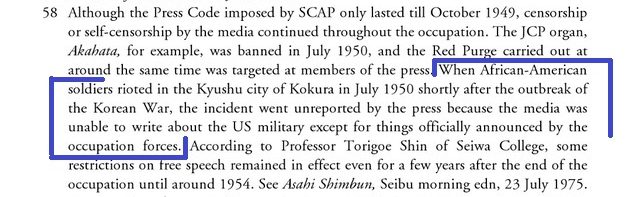

The lack of English-language information is due in large part to the press censorship of those times. According to a Japanese library website (CRD), the only contemporary newspaper account is from July 15: 朝日新聞 昭和25年7月15日(北九州版) Asahi Shimbun, 1950 July 15 (Kitakyushu version). Similarly, Media, Propaganda and Politics in 20th-Century Japan states that on the day of the riots, “the Western Asahi news car drove around the streets of Kokura that night using a loudspeaker to advise people not to leave their homes but they made no mention of the American soldiers. No news about the incident was printed in the Asahi the next day.” Furthermore, a footnote to Grassroots Pacifism in Post-War Japan: The Rebirth of a Nation, states “the incident went unreported by the press because the media was unable to write about the US military except for things officially announced by the occupation forces.”

Of course, the residents of Kokura who experienced the incident firsthand would not require a newspaper to tell them what happened; the event was so well known to Matsumoto that, when he moved to Tokyo in 1953, he was surprised to learn that nobody in Tokyo had heard of the Kokura Incident (this is described in the intro to 「黒 地の絵」-松本清張のダイナミズム- 評伝松本清張:昭和33年 Matsumoto Seicho’s Kuroji-no-E His Origin of Dynamism A Critical Biography of Matsumoto Seicho, 1958.)

If Matsumoto was motivated to publicize the Kokura incident, it’s possible he succeeded too well; his story has arguably overshadowed the actual events and may now distract from the truth. Matsumoto’s fictional story provides far more detail than what’s available for the real events. Given Matsumoto’s prominence as a writer, it’s likely that the fictional event is better known the than the real event. (For context about Matsumoto, he has been called the “undisputed dean of Japanese mystery writers”* and was the “best-selling and highest earning author in the 1960s”* Additionally, several of his books were adapted into films, including Zero Focus (1961), a favorite of mine.)

An additional distraction is Matsumoto’s racist depiction of the black American soldiers, most notable in a passage describing the psychological impact of drums on the black soldiers, implying that they are primitive and distinct from the Japanese. This, and similar passages are described in The American Occupation of Japan and Okinawa: Literature and Memory (page 88):

Racism is briefly mentioned by Duchess Harris, a Professor of American Studies at Macalester College in her essay, “How negative stereotypes in material culture impact global politics”, she writes:

“The image of the Black GI as rapist has become something of a staple in Japanese pornography and films about the Occupation. The Black rapist trope also appears in Matsumoto Seicho’s short story, Kuroji no e.” [emphasis added]

(Broken link as of 2/14/23; original link: curri.miyakyo-u.ac jp/curri-ex/pub/maca/rep02/harris [dot] html)

Racial elements are also recognized in Japanese sources; for example, one blog notes:

“また清張は、この事件が祇園祭りの日に起こったことに着目し、打ち鳴らされる太鼓の音を聞いて、黒人兵たちはアフリカの原始の血を呼び起こし、犯罪に走ったという設定にしている。しかしこれは、黒人をステレオタイプ化していると見なされて、人種差別の問題にふれてくる。”

[rough translation] “Seicho focuses on the fact that this incident happened on the day of the Gion Festival, listening to the sound of the beating drum, evoking Africa in the blood of the primitive black soldiers, pushing the men towards the crime . However, this is considered to be stereotyping of black people, which touches the problem of racial discrimination.”

The racial component of the Kokura Incident (and of Matsumoto’s book) makes it a tricky topic to write about; while the events are interesting and noteworthy, writing about the incident may be seen as either an indictment of Matsumoto or as a defense of racism. Indeed, most English-language references to Matsumoto’s story focus on his treatment of race; conversely, sources that call attention to the crimes of American servicemen in Japan are often written from a white-supremacist perspective (I can provide links upon request, but would prefer not to link directly to these sites).

Accepting the tricky nature of this topic, I want to challenge the notion that Matsumoto was biased or racist in his selection of the Kokura incident as a writing topic. Matsumoto may very well have been racist in his writing of this story, but the topic and the events cannot not be dismissed as a mere “racist trope”.

Harris’s statement that the “Black rapist trope also appears in Matsumoto Seicho’s short story” is a factual statement; to the extent that one can define a “Black GI as rapist” trope, then it can be identified in Matsumoto’s story. But Harris’ statement can be misleading; it can imply that Matsumoto chose to write about “Black GI as a rapist” because it was an available racist trope. (In the context of writing, my definition of a “racist trope” would be a theme, motif or scenario, etc, based on (generally negative) racial stereotypes that are used by a writer due to some combination of laziness, racism, and inability/lack of interest in representing a person or group of people accurately.)

I don’t doubt that racist tropes exist, but I don’t think it’s accurate to say that Matsumoto’s chose his topic because it was a racist trope. Matsumoto had several reasons to write about the Kokura incident. First, Matsumoto was born in Kokura and lived there at the time of the events. It is natural that he would have been disturbed by the events; furthermore, he must have been surprised and angry to learn that the incident was unknown in Tokyo. Given his proximity to the events it is understandable that he would select the incident for the topic of a story.

Discussions of Matsumoto’s work that focus on the racist elements his work do so at the expense of sympathizing with the victims of the crimes. Let’s revisit Lavish are the Dead: Re-envisioning Japan’s Korean War 死者の奢り あらためて日本の朝鮮戦争を思い浮かべる; in the following passage, Morris-Suzuki provides a “why” for the soldiers’ actions that builds sympathy for the ‘rioters’:

“The departure of the 24th Infantry Regiment to Korea was chaotic. The soldiers were supposed to sail from Sasebo, but were instead diverted to Camp Jōno, where there was inadequate accommodation to house them. From there, as they discovered, they were to be shipped to Korea in a hastily assembled flotilla of ‘fishing boats, fertilizer haulers, coal carriers and tankers’. It was against the background of this chaos, as the miseries of their situation and the prospect of impending death confronted the soldiers, that the mass breakout and riot occurred.” [emphasis added]

Word choice is important; if we describe the events as a “mass breakout” or “riot”, the incident becomes benign; however, if we choose to describe the event as a “mass rape”, it is more difficult to ignore the brutality of the events, and harder to accept that the events were the natural result of “the background of…chaos”, as Morris-Suzuki describes. Word choice also plays a role in a later passage by Morris-Suzuki:

“Although those involved were only a small fraction of the three thousand members of the regiment, from the point of view of the citizens of Kokura the riot was a traumatic introduction to the realities of the Korean War and American society.” (link)

The description of the rioters as a “small fraction” of the overall size of the regiment is intended to minimize the size of the riots; but what it the purpose of minimizing the events? To a Japanese woman living in the village of Kokura, the site of 100 to 250 rioters would be terrifying, especially if they committed dozens rapes, as has been reported. The fact that 2800 non-rioting soldiers elsewhere in the city would come not only as little comfort to the victims, and has no relevance in an objective description of the events.

Even the authoritative work by Kashima Takumi includes the odd euphemism “committed excesses” in place of “rape” or more specific terms:

The above passages comprise most of the English-language resources available online; these passages are contained within larger works that use the events to fit a larger theme and agenda. None of the accounts place the factual events of the Kokura incident at the forefront. I’ve attempted to bring light to the events by presenting “just the facts” with minimal ideological interference; however, I acknowledge there can be bias in the mere selection of topics that we (or I) choose to write about (this is a topic I intend to address in a separate post). I also don’t mean to ignore the context provided by Morris-Suzuki regarding the tension between black soldiers and white officers. This topic deserves lengthier attention than I can provide here, but let me point you to the case of Leon Gilbert, a member of the 24th Infantry Regiment who was court martialed and sentenced to death for disobeying a “suicidal” order from his superior. See also the links at the bottom of this post, under the heading “Race in the American military (and in the Occupation of Japan)”.

(III) The murder story

The puzzle of the Kokura incident becomes more complex when considered in tandem with the murder of July 4, 1950. Was Matsumoto aware of this murder? And did the details of this murder influence his writing of Kuroji no e? I wouldn’t be surprised if this were true, considering that the details of the July 4th murder share similarities with the plot of Matsumoto’s book. In fact, the details (and dates) align so closely that I initially assumed these events took place on the same day.

Unlike the Kokura incident, the events of the ‘Murder on the 4th of July’ are well-documented in contemporary court documents; the trial took place in Kokura on August 28th and 29th, 1950 and the judge’s opinion and review by JAG Corp. officers are available online; see: CM number 343576: UNITED STATES v. Recruit JAMES L. CLARK (RA 14267271), Company B, 11th Engineer (C) Battalion, APO 24 (starting with page 1).

According to the court report, at around 0600 on the morning of July 4, 1950, a drunk James Clark entered the home of the Kaki family and murdered both parents and two children of the family’s three children with a knife. Incredibly, one of the children did not die instantly and was able to write down the events prior to his death. The other child escaped harm.

The victims were: Kaki Shizu (mother); Kaki Magojiro (father); Kaki Katsukaza (son); Kaki Kyo (son)

I suggest you read the fascinating and terrifying court transcript; these excerpts provide key details:

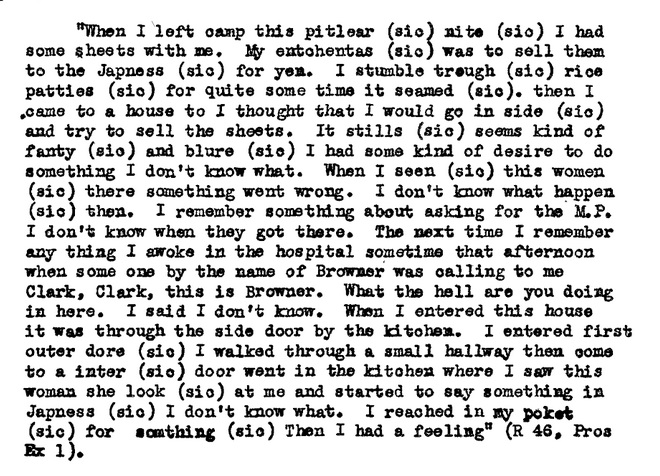

A note about James Clark: he had completed a mere six grades of public school, which is apparent in the statement he wrote while under arrest:

Although James Clark was sentenced to death by the court martial, a letter signed by Major General Franklin P. Shaw asked that the death sentence be commuted to life in prison. It appears that Clark’s death sentence was indeed commuted, as his name does not appear on available lists of military executions (see: Capital punishment by the United States military). Additionally, the following list of military executions notes the final sentence as “DD TF Life”, which I interpret as Dishonorable Discharge, Total Forfeiture (of benefits), and Life Sentence. (Source; full PDF)

(IV) The movie version (?)

The Kokura Incident and the ‘Murder on the 4th of July’ are regrettable events that may have fallen through the cracks of history had it not been for Seicho Matsumoto. There is something cinematic about these events – gruesome murders, and dozens (or hundreds) of soldiers marauding through the night. It shouldn’t be a surprise that rumors of a Kuroji no e 「黒地の絵」 film adaption have circulated; the blog entry, イーストウッドに「黒地の絵」の映画化を Eastwood film adaptation of “black paintings”, mentions that Akira Kurosawa, among other directors, was once interested in making a Kuroji no e 「黒地の絵」 film; that post even speculates about a Clint Eastwood adaptation, citing Eastwood’s “interest in wars and racial discrimination” (戦争や人種差別に関しては、大きな関心を抱き).

And what about Spike Lee スパイク・リー? His name was suggested by a Twitter user last year.

Links and references:

Glossary:

- 北九州 小倉事件 = Kitakyushu Kokura incident

- 小倉事件 = Kokura incident

- 小倉黒人米兵集団脱走事件 = “Kokura black American soldier group breakout” (Japanese Wikipedia)

Korean war & Camp Jono (Kokura, Japan)

- Background information: “The Korean War and Japanese Ports: Support for the UN Forces and Its Influences” (PDF), section titled “(3) Kanmon Port (Kitakyushu Port, Shimonoseki Port)”

- Lavish are the Dead: Re-envisioning Japan’s Korean War 死者の奢り あらためて日本の朝鮮戦争を思い浮かべる: see the section titled “Ghost ships”

- “Korean Battlefields Give Up Bodies Of 1,800 U.S. ‘Unknown Soldiers’” (The Day (New London, Connecticut), January 11, 1952)

Matusumoto’s book:

- Japanese title: 『黒地の絵』 (Kuroji no e)

- 2011 English translation: Tattoo on the black soldier’s breast : “It’s only me that remembers it.” : English translation of Matsumoto Seicho’s Kuroji no e by Seicho Matsumoto; translated by Takumi Kashima

- Various English translations of the book’s title: (1) A Picture Against a Black Background; (2) Painting on a black canvas; (3) Picture on a Black Background; (4) Picture on black cloth; (5) Tattoo on the black soldier’s breast; (6) The Black Skin Tattoo

- Racism in the book:

- Reference to African rhythm: 職人列伝【1】破顔のリズム職人、Jo Jones

- “How negative stereotypes in material culture impact global politics” (Harris) (Broken link)

- Playing in the Shadows: Fictions of Race and Blackness in Postwar Japanese Literature, by William H. Bridges (2020)

- Comment on ‘Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation’: War through the eyes of everyday Oita citizens (The Japan Times):

“I translated that novella decades ago. Matsumoto was known as a leftwing writer, but his views of African-American soldiers would strike most Westerners as racist…The white American soldiers are seen as lording it over both Blacks and Japanese, as “colored people” (有色人種)…I realize now why my translation was unpublishable.”

Resources about the Kokura incident (English):

- Lavish are the Dead: Re-envisioning Japan’s Korean War 死者の奢り あらためて日本の朝鮮戦争を思い浮かべる (PDF version)

- References to: ‘Chōsen sensō shitai shorihan: Aru jinruigakusha no kaisō’, in Tōkyō 12-Chaneru Hōdōbu ed, Shōgen: Watashi no Shōwashi, vol 6, Gagugei Shorin, 1969, which can be found at one or both of the following listings:

- 混乱から成長へ (証言・私の昭和史 / 東京12チャンネル報道部, 6) From chaos to growth (testimony, my Showa History / Tokyo Channel 12 news department, 6)

- 「証言私の昭和史 6」 東京12チャンネル報道部 編 “Testimony my Showa History 6” Tokyo Channel 12 news department

- Grassroots Pacifism in Post-War Japan: The Rebirth of a Nation, by Mari Yamamoto (2004)

- Black Soldier, White Army: The 24th Infantry Regiment in Korea, by William T. Bowers, William M. Hammond, George L. MacGarrigle; this book’s account of the Kokura incident includes interviews; see, for example, footnote 63 on page 80

- Media, Propaganda and Politics in 20th-Century Japan, by The Asahi Shimbun Company

- The Korean War and Japanese Ports: Support for the UN Forces and Its Influences (PDF), (link) ISHIMARU Yasuzo (link)

- Described generally as “the mass escape of U.S. soldiers”, and in detail: “Fukuoka Ken Keisatsu Honbu, Fukuoka Ken Keisatsu Shi, Syowa Zenpen, pp. 848-856. On July 11, 1950, when the 24th Infantry Regiment that was stationed in Gifu City arrived at Kokura Camp (current Jono, Kokurakita-ku, Kitakyushu) to invade the Korean Peninsula, some 200 fully-armored U.S. soldiers escaped. They were involved in at least 70 crimes consisting of assaults and robberies.”

- The American Occupation of Japan and Okinawa: Literature and Memory

Japanese sources:

- Kashima, Takumi 加島 巧 (author): this appears to be the most comprehensive resource about the Kokura incident: 「黒 地の絵」-松本清張のダイナミズム- 評伝松本清張:昭和33年 Matsumoto Seicho’s Kuroji-no-E His Origin of Dynamism A Critical Biography of Matsumoto Seicho, 1958

- Japanese Wikipedia: 小倉黒人米兵集団脱走事件 (Kokura black American soldier group breakout)

- May 9, 1993 Kyushu TV-Asahi biography of Seicho Matsumoto (referenced here, page 80)

- CRD list of sources: 松 本清張の小説『黒地の絵』の題材にもなった事件で朝鮮戦争のとき小倉市の米軍キャンプから米兵が脱走した事が載っている資料を紹介してください。 Documentation that American soldiers from the US military camp of Kokura City escaped during the Korean War incident, which also became the subject of novels of Seicho Matsumoto “black picture”.

- Japanese resource: 松本清張「黒地の絵」論 Seicho Matsumoto “Black Picture” theories

- 1975 interviews in the Fukuoka Prefectural edition of the Asahi, as noted by Media, Propaganda and Politics in 20th-Century Japan

- A drainage ditch noted as an escape route for the soldiers [ 黒人兵が脱走した排水溝], according to 小倉黒人米兵集団脱走事件(小倉事件):

Sources referenced in the Japanese Wikipedia account of the Kokura incident:

- 『激動二十年―福岡県の戦後史』 毎日新聞西部本社刊 “Turbulent two decades – postwar history of Fukuoka Prefecture,” Mainichi Shimbun western edition

- 『目録20世紀 1950』 講談社刊 “Inventory 20 Century 1950” published by Kodansha

- 『20世紀全記録』 講談社刊 “20 century all record” published by Kodansha

- 『朝鮮戦争』 児島襄著 “Korean War” Author Jo Kojima

Race in the American military (and in the Occupation of Japan):

- Race and American Military Justice: Rape, Murder, and Execution in Occupied Japan

- Chewing Gum and Chocolate (book)

- From a Times review: American Culture, Riding a Mushroom Cloud

- “If Mr. Tomatsu documented the ambiguous relationship of the Japanese to an invading culture, he was also aware of the contradictions and hypocrisy of the occupiers. In a multipart series, published in 1960 in the magazine Asahi Camera, he focused on the segregated, black units of three United States military bases in Japan. In so doing, he questioned the power relations and paradoxes of cultural occupation, both within Japan and the United States.

- “Chewing Gum and Chocolate” contains similarly ironic pictures of African-American soldiers flashing the black power salute at the height of the Vietnam War. “The fists the black soldiers raised to the Okinawan sky,” Mr. Tomatsu speculated, “might have been an expression of antiwar sentiment by people who are extremely unfree and know the stupidity of fighting a war ‘for the sake of freedom.’ ””

- From an Art in America review: Nippon Interzone

- “Tomatsu never captured servicemen doing anything really wrong, but he knew how to make them look bad in ambiguous situations. Many of the most famous examples use the compositional techniques of modernist ostranenie (extreme angles, tilting ground planes) to render their subjects doubly disconcerting. In one image, the camera looks up at a group of crew-cut servicemen, all laughing, one raising his foot as if to stomp on Tomatsu’s face. Blacks come across as especially ugly. Two stand in front of a bar, overcome with laughter as a passing Japanese woman flinches away from the camera. The face of a black sailor, captured in close-up turning his head, displays a sneer that is probably accidental but no less grotesque because of it.”

- “A look at the last U.S. soldier executed by the military” (CNN)

- “The biggest concern with the military death penalty was that it fell disproportionately on African-American soldiers,” says Eugene R. Fidell, who teaches military justice at Yale Law School.

- During World War II, blacks accounted for less than 10% of the Army. During the war, 70 soldiers were executed in Europe and, of those, 55 were black, wrote Dwight Sullivan, a military law expert, for the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center, which analyzes and studies issues surrounding capital punishment.”

About the author, Seicho Matsumoto

- Obituary: Seicho Matsumoto (The Independent)

- Exposé Writing of the 1950s and Matsumoto Seichō’s Nihon no kuroi kiri (Japanese, broken link)

- Pro Bono: by Seicho Matsumoto (translated by Andrew Clare), Review by Jack Cooke (The Japan Society) – broken link

- One of Matsumoto’s stories was responsible popularizing Aokigahara Jukai 青木ヶ原, the so-called ‘Suicide Forest’, near Mt. Fuji

- A newspaper story about the suicide forest: “Japanese recover 6 skeletons in suicide haven” (The Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), October 19-20, 1983)

- Matsumoto Seicho Memorial Museum 松本清張記念館 (Kitakyushu, Japan; address: 福岡県北九州市小倉北区城内2番3号; Google Maps)

See also:

- The “Oh, Mistake” incident, and crime in apres-guerre Japan 「オー・ミステーク」事件と「アプレゲール犯罪」

- Race in post-war Japan: Chico Lourant, the Black Sun of Shibuya

- American military observations in the early days of the Occupation: Bombing Nagasaki: the scrapbook

- Occupied Japan: Maps of American occupied Tokyo, 1948 GHQ東京占領地図

- Occupied Japan: Made in Occupied Japan: Eikeisha clock (1947-1952)

- Observations on life during the Occupation: “You in Tokyo” – THE NEW YORKER, 1946

[…] at the real-life Yawata Steel Works 八幡製鉄所 (map) in Kitakyushu 北九州市 (near Kokura) is one of the film’s main characters. Although the film is de facto propaganda for the steel […]