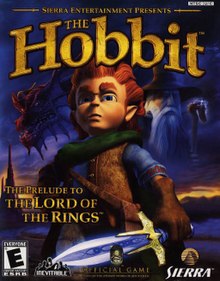

The Hobbit (2003 video game)

| The Hobbit | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Inevitable Entertainment (GameCube, PlayStation 2, Xbox) The Fizz Factor (Microsoft Windows) Saffire (Game Boy Advance) |

| Publisher(s) | Sierra Entertainment |

| Composer(s) |

|

| Platform(s) | Game Boy Advance, GameCube, PlayStation 2, Xbox, Microsoft Windows |

| Release | Game Boy AdvanceGameCube, PlayStation 2, Xbox, Microsoft Windows |

| Genre(s) | Action-adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The Hobbit is a 2003 action-adventure game developed by Inevitable Entertainment for the GameCube, PlayStation 2 and Xbox, by The Fizz Factor for Microsoft Windows, and by Saffire for the Game Boy Advance. It was published by Vivendi Universal Games subsidiary Sierra Entertainment.

The game is based on the 1937 novel of the same name by J. R. R. Tolkien, and has no relationship with the Peter Jackson-directed The Lord of the Rings film trilogy. At the time, Vivendi, in partnership with Tolkien Enterprises, held the rights to the video game adaptations of Tolkien's literary works, whilst Electronic Arts held the rights to the video game adaptations of the New Line Cinema films. The game sticks very closely to the plot of the novel, although it does feature some minor characters not found in Tolkien's original.

The Hobbit received mixed reviews, with critics praising its fidelity to the source material, but finding the gameplay unoriginal and too easy.

Gameplay[edit]

The Hobbit is primarily a platform game, with elements of hack and slash combat, and some rudimentary puzzle aspects, played from a third-person view (the Game Boy Advance version is played from an isometric three-quarter top-down view).[4] The player controls Bilbo Baggins, the majority of which is built around basic platforming; Bilbo can jump, climb ropes and ladders, hang onto ledges, swing on vines, etc. Progression through the game is built around quests. Every level features multiples quests which must be completed in order to progress to the next level. Many of the levels also feature optional sidequests which do not have to be completed, but which can yield substantial rewards if they are.[5]

Bilbo has three weapons available to him during combat. He begins the game with his walking stick, which can be used in melee combat, and stones, which he can throw. Later in the game, he acquires a dagger, Sting. All three weapons can be powered up by finding magical scrolls scattered throughout the game. These scrolls grant such abilities as increased damage, jump attacks, double and triple combo attacks, and charged attacks.[6] The game also features the use of the One Ring, which can temporarily turn Bilbo invisible, allowing him to avoid certain enemies.[7][8]

Bilbo's health system is based upon "Courage Points". At the start of the game, he has three health points. For every 1000 Courage Points he collects, he acquires an extra health point. Courage Points come in the form of diamonds, with different colors representing different numerical values. For example, a blue diamond equals one Courage Point, a green diamond equals ten, etc. Bilbo's progress in gaining a new health point is shown in his courage meter, which is on screen at all times.[9] For the most part, Courage Points are scattered throughout the levels and awarded for completing quests. Some of the higher value diamonds are hidden off the main path of a level, while the lowest level diamonds (blue) are often used to indicate to the player where they are supposed to be heading.[10]

At the end of each chapter, the player is taken to a vendor, where they can spend the in-game currency, silver pennies. Items available for purchase include stones, healing potions, antidotes, skeleton keys, temporary invincibility potions, additional health points, and the ability to increase the maximum number of stones and health potions which Bilbo can carry.[11]

Pennies, healing potions, antidotes and, often, quest items and weapon upgrades can be found in chests throughout the game. Often, chests will simply open when Bilbo touches them, but sometimes, the chests are locked, and Bilbo must pick the lock. This involves a timed minigame in which the player must align a pointer or select a specific target. Some chests will have only one minigame to complete, but chests containing more important items will have more, up to a maximum of eight. If Bilbo misses the pointer/target, the timer will jump forward; if he hits a red pointer or target, the minigame will end immediately. Penalties for failing to open a chest include losing health points or being poisoned. If the player has a skeleton key, they can bypass the minigames and open the chest immediately.[12]

Plot[edit]

The wizard Gandalf arrives in the Shire to get the hobbit Bilbo Baggins to join thirteen dwarves led by Thorin Oakenshield as a thief, for a journey to the Lonely Mountain to reclaim the dwarves' treasure from the dragon Smaug. During the journey, Bilbo meets the injured elf Lianna, and helps her. At the Misty Mountains, the group is attacked by goblins; after the ensuing fight, Bilbo falls into the caves and is knocked unconscious. He awakens alone and lost, and wanders in the dark, finding a ring and meeting Gollum. After reuniting with the dwarves and Gandalf, they are attacked by goblins and wargs, but are saved by a band of eagles who take them to Mirkwood Forest. While wandering through the forest, Bilbo and the dwarves get captured by Wood Elves and taken to the dungeons of Thranduil. Using the power of the ring, Bilbo enters Thranduill's hall, where he meets Lianna, who helps him free the dwarves. They escape to Lake-town, a settlement close to the Lonely Mountain. Bilbo becomes friends with Bard, captain of the town guard, who shoots and kills Smaug when the dragon attacks the town.

Later, an army of humans and wood elves head toward the Lonely Mountain to claim the dwarves' treasure; to prevent a battle, Bilbo sneaks out of the mountain with the Arkenstone, a treasure of great importance, and gives it to Bard, who offers to return it to Thorin in return for the rest of the treasure. Thorin refuses, denouncing Bilbo as a traitor, and a battle eventually breaks out between five armies who want the dwarf treasure. The battle ends with the goblins defeated, and the humans, elves, and dwarves having made peace; Thorin, mortally wounded, apologizes to Bilbo. Lake-town begins to rebuild, and Bilbo and Gandalf return to the Shire.

Development[edit]

"The Hobbit is one of the pre-eminent fantasy works of all time and is perfectly suited to be the inspiration for a great game. The book provides a tremendous amount of rich material from which we expect to make a fantasy game that lives up to the extremely high expectations of Tolkien's fans worldwide."

— Mike Ryder; Sierra Entertainment president[13]

Originally, Sierra's holding company, Vivendi Universal Games, had tapped Sierra to publish a game based on the first book in Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Fellowship of the Ring. As Vivendi owned the rights to adapt video games of Tolkien's literature, and Electronic Arts to adapt the New Line Cinema film series, the game would have no connection to Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. Ultimately, however, Vivendi released The Fellowship game under their "Black Label Games" banner, and instead, had Sierra begin work on an adaptation of Tolkien's earlier novel, The Hobbit.[14]

The game was announced on February 25, 2002, when Sierra Entertainment revealed it was being developed as a GameCube exclusive by Inevitable Entertainment.[13] Although not scheduled for release until late 2003, a non-playable demo was made available at the 2002 E3 event in May.[15] After E3, Sierra explained that because the novel is quite short, parts of the story had to be expanded in the game to ensure the narrative was of sufficient length (for example, Bilbo's rescue of the dwarves from the spiders in Mirkwood is much longer and more detailed in the game than in the book), and considerably more combat was added to the story. However, the developers were under strict instructions not to deviate from the basic plot of the novel. Sierra was in constant communication with Tolkien Enterprises, and had also employed several Tolkien scholars to work with the game developers. Tolkien Enterprises had veto rights on any aspects of the game which they felt strayed too far from the tone of Tolkien's novel and his overall legendarium.[16] In the early stages of development, there were plans for players to control Gandalf during the Battle of the Five Armies, but this idea was ultimately abandoned.[16]

"Because the book was a bit lighter than Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings series, the development team wanted to go with a style that conveyed a little bit of whimsy. That's how we ended up with the very colorful, stylized world in The Hobbit. There are a lot of very interesting settings in The Hobbit, and we wanted to do them justice. By opening up the color palette, and staying away from the drab browns and grays, we were able to create a very distinctive set of levels. No two levels look the same, and they all look great. Once people get to see how much visual variety there is in this game, they are going to love it."

— Tory Skinner; Vivendi Universal Games producer[17]

On July 19, 2002, Sierra announced the game was also being released for Game Boy Advance, developed by Saffire.[10] Sierra also revealed the GBA version would feature more stealth and less combat than the GameCube version, and would follow the plot of the novel a little more closely.[4] On February 24, 2003, they announced the game would also be released for PlayStation 2, Xbox and Windows, with Inevitable Entertainment handling the PlayStation and Xbox versions, and The Fizz Factor developing the Windows version.[10] Ken Embery, Sierra's executive producer on the game, stated "the plan all along was to be multiplatform. But we were starting out with GameCube as the lead and were just holding our cards close to our chest before announcing all of our other titles. The PS2 is, of course, the most problematic of all the platforms for developers to deal with and we wanted to make sure that we had solid prototypes and running proof of concept versions before we made it public".[18] Embery explained the art style of the game was influenced by the Super Mario and The Legend of Zelda games, and in that sense, was aimed at a slightly younger audience than the Lord of the Rings films.[18] Tory Skinner, of Vivendi Universal Games, further stated "The Hobbit was written for a younger audience, so it made sense to create a game that would be enjoyable for younger kids, as well as adults. We looked at the different types of game we could do, and an action-adventure game with a heavy emphasis on the action seemed like the best way to go. We didn't want to make the game inaccessible by loading down gamers with hard-core RPG gameplay."[17]

Lead designer Chuck Lupher said the gameplay was also influenced by The Legend of Zelda games;

when we first sat down we took a look at a lot of different game styles that we thought would do the title justice, and essentially we wanted a real-time action-adventure game similar to [The Legend of Zelda]. We looked at a lot of different games. We were all big platform games fans, too, and one of the things we wanted to do was break free from being locked to the ground. We wanted to have a lot of exploration, environment navigation and combat challenges because the story really lends itself to that. So it's really an action-adventure.[18]

At the 2003 Game Developers Conference in March, a playable demo was made available on GameCube, PlayStation 2 and Xbox, featuring the opening level in Hobbiton and a later level in the caves of the Misty Mountains.[19][20] In June, Inevitable revealed the three console versions would all run off their own multiplatform in-house game engine.[8] The GBA version used its own engine developed by Saffire, but the gameplay and storyline were derived from Inevitable's build.[21] At the 2003 E3 event in June, a three level playable demo was made available for all systems, featuring the opening level, the spider level in Mirkwood and the level were Bilbo sneaks into Smaug's lair. It was also announced that the release date for the game had been pushed back from September to November to allow for some final tweaking.[10]

Music[edit]

The game's score was composed by Rod Abernethy, Dave Adams and Jason Graves, and recorded live with the Northwest Sinfonia in Seattle. The acoustic music was recorded with individual Celtic musicians from Raleigh, North Carolina.[17] According to lead programmer Andy Thyssen, the game has

a pretty complex music logic that blends together the level themes. So we have some very different locales, each with its own melody and theme, and we blend in as you approach certain characters, or as you move in and out of combat or hazardous situations. It really adds a lot to the game to push the emotions of the player around like that.[18]

According to Abernathy, the game needed a music score that was "simple, melodic and organic" for Bilbo's adventures through Middle Earth, switching to bold and dramatic for the combat scenes. He explained that Tolkien's literature evokes the sound of fiddles, wood flutes, bagpipes, guitar, mandolins and bodhráns; and during fights or battles, "low chugging strings, dramatic percussion and moving brass lines and stabs".[22]

The team was given a budget to create seventy-five minutes of original music, which was to be divided into two categories; "acoustic instrumental for Bilbo's exploration and live orchestral for the action/combat scenes."[22] Abernathy explains

Most music cues in a scene are normally 20 to 30 seconds long and are rated in levels of intensity. As the scene is played, these cues must fit together in any given order but still sound cohesive. To finish out the scene, there is a "Win-Stinger" and a "Lose-Stinger" to match each level of intensity, depending on where the player stops game play during the scene. This process was carried to produce music for more than 210 music cues spanning over six chapters and 40 scenes.[22]

The team would record demos for every scene in the game, and send them to Chance Thomas, director of music at Tolkien Enterprises, who would send them back advice.[22]

In his review of the game, IGN's Matt Casamassina wrote "the music soundtrack is fantastic. It's orchestrated, wholly atmospheric, and varied. The scores provide a mixture of soft, delicate backgrounds that enrich the mood of the locales and big, banging music that successfully drives home accomplishments. If more developers took the time to implement soundtracks like this the world would be a better place."[23] At the 2004 Game Audio Network Guild (G.A.N.G.) Awards, the soundtrack won the "Best Original Soundtrack."[24]

Reception[edit]

| Aggregator | Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBA | GC | PC | PS2 | Xbox | |

| GameRankings | 63%[25] | 65%[26] | 62%[27] | 64%[28] | 66%[29] |

| Metacritic | 67/100[30] | 61/100[31] | 62/100[32] | 59/100[33] | |

| Publication | Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBA | GC | PC | PS2 | Xbox | |

| Eurogamer | 5/10[34] | ||||

| GameSpot | 6.5/10[35] | 6.5/10[36] | 6.5/10[37] | ||

| GameSpy | |||||

| IGN | 6.5/10[40] | 7.5/10[41] | 7.5/10[42] | 7.5/10[23] | 7.5/10[43] |

| Nintendo Power | 3.5/5[44] | 3.7/5[45] | |||

| Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine | |||||

| Official Xbox Magazine (US) | 5.5/10[47] | ||||

| PC Gamer (US) | 67%[48] | ||||

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| Game Audio Network Guild Awards | "Best Original Soundtrack" (2004)[24] |

The Hobbit received mixed reviews across all platforms, according to the review aggregators Metacritic and GameRankings, with aggregate scores ranging from 59% to 67%.[a]

IGN called the Game Boy Advance version a good action game with impressive graphics, but thought it lacked a sense of grandeur, with all the quests and battles coming across as trivial and unimportant.[40] Reviewing the other versions, they still enjoyed the action and visuals, but said that they found the gameplay similar to The Legend of Zelda, but not executed as well; they primarily recommended it to "hardcore Tolkien fans" and young players.[23][41][42][43] GameSpot and GameSpy agreed that it might appeal to Tolkien fans, praising its faithfulness to the book, but found the gameplay derivative and not enough to hold up next to the story,[35][36][37][38] although GameSpy also said in their review of the PC version that it might be disappointing to everyone due to looking "too juvenile" for adults, being too challenging for children, and unappealing to Tolkien fans due to its adaptation of the book into a "lightweight, cartoonish platformer".[39] Eurogamer panned the Xbox version, calling it "painfully average", with subpar graphics, repetitive levels, and too many "find-the-key" scenarios.[34]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "The Hobbit (GBA)". GameSpy. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ a b "The Hobbit". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ "The Hobbit (PlayStation 2)". GameSpy. Archived from the original on October 24, 2014. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ^ a b "The Hobbit Q&A". GameSpot. July 19, 2002. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Lamb, Kevin (2003). "Quest Log". The Hobbit PlayStation 2 Instruction Manual. Sierra Entertainment. pp. 21–22. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ Lamb, Kevin (2003). "Training and Scrolls". The Hobbit PlayStation 2 Instruction Manual. Sierra Entertainment. p. 14. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ Lamb, Kevin (2003). "Stealth Movement". The Hobbit PlayStation 2 Instruction Manual. Sierra Entertainment. p. 29. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ a b Sulic, Ivan (June 3, 2003). "Hands on a Hobbit". IGN. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Lamb, Kevin (2003). "Courage Points". The Hobbit PlayStation 2 Instruction Manual. Sierra Entertainment. p. 15. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Torres, Ricardo (June 5, 2003). "The Hobbit Impressions". GameSpot. Archived from the original on November 24, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Lamb, Kevin (2003). "End of Chapter Vendor". The Hobbit PlayStation 2 Instruction Manual. Sierra Entertainment. pp. 16–17. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ Lamb, Kevin (2003). "Picking Locks". The Hobbit PlayStation 2 Instruction Manual. Sierra Entertainment. pp. 13–14. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ a b "The Hobbit Announced for GameCube". IGN. February 25, 2002. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ "Lord of the Games". IGN. December 2, 2002. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ "E3 2002: First Look: The Hobbit". IGN. May 22, 2002. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ a b Satterfield, Shane (July 15, 2002). "The Hobbit Preview". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c "The Hobbit Q&A". GameSpot. May 12, 2002. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Casamassina, Matt (February 24, 2003). "The Hobbit Interview". IGN. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Goldstein, Hilary (March 5, 2003). "GDC 2003: Eyes on The Hobbit". IGN. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Colayco, Bob (March 7, 2003). "GDC 2003: The Hobbit Impressions". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Harris, Craig (June 5, 2003). "The Hobbit". IGN. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Abernathy, Rod (October 1, 2003). "Live Orchestra for The Hobbit". Mixonline.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2015. Retrieved July 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c Casamassina, Matt (November 12, 2003). "The Hobbit Review (PS2)". IGN. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "2004 G.A.N.G Awards". G.A.N.G. Archived from the original on July 5, 2015. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ a b "The Hobbit for GameBoy Advance". GameRankings. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "The Hobbit for GameCube". GameRankings. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "The Hobbit for PC". GameRankings. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "The Hobbit for PlayStation 2". GameRankings. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "The Hobbit for Xbox". GameRankings. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "The Hobbit (GameBoy Advance)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "The Hobbit (Gamecube)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 10, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "The Hobbit (PC)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b "The Hobbit (PlayStation 2)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Bramwell, Tom (January 23, 2004). "The Hobbit Review (Xbox)". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on June 13, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Davis, Ryan (November 20, 2003). "The Hobbit Review (PC)". GameSpot. Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Davis, Ryan (November 18, 2003). "The Hobbit Review (PS2)". GameSpot. Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Davis, Ryan (November 18, 2003). "The Hobbit Review (Xbox)". GameSpot. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Freeman, Matthew (November 5, 2003). "The Hobbit Review (GameCube)". GameSpy. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Bennett, Dan (December 13, 2003). "The Hobbit Review (PC)". GameSpy. Archived from the original on October 24, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Tierney, Adam (December 2, 2003). "The Hobbit Review (GBA)". IGN. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Casamassina, Matt (November 11, 2003). "The Hobbit Review (GameCube)". IGN. Archived from the original on October 27, 2023. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Casamassina, Matt (November 12, 2003). "The Hobbit Review (PC)". IGN. Archived from the original on October 27, 2023. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Casamassina, Matt (November 12, 2003). "The Hobbit Review (Xbox)". IGN. Archived from the original on October 27, 2023. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ "The Hobbit Review (GBA)". Nintendo Power. December 2003. p. 150.

- ^ "The Hobbit Review (GameCube)". Nintendo Power. December 2003. p. 152.

- ^ "The Hobbit Review (PS2)". Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine. January 2004. p. 120.

- ^ "The Hobbit Review (Xbox)". Official Xbox Magazine. January 2004. p. 63.

- ^ "The Hobbit Review (PC)". PC Gamer: 76. February 2004.

- 2003 video games

- 3D platformers

- Action-adventure games

- The Fizz Factor games

- Game Boy Advance games

- GameCube games

- Midway Studios Austin games

- PlayStation 2 games

- Saffire games

- Sierra Entertainment games

- Single-player video games

- Video games about dragons

- Video games based on Middle-earth

- Video games based on novels

- Video games developed in the United States

- Video games scored by Jason Graves

- Video games scored by Rod Abernethy

- Vivendi Games games

- Windows games

- Works based on The Hobbit

- Xbox games