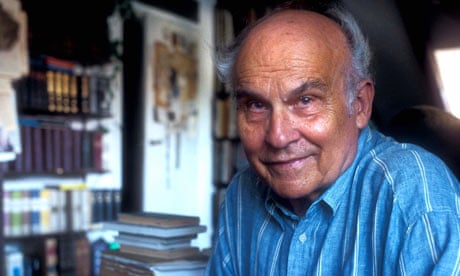

He has been voted the greatest journalist of the 20th century. In an unparalleled career, Ryszard Kapuściński transformed the humble job of reporting into a literary art, chronicling the wars, coups and bloody revolutions that shook Africa and Latin America in the 1960s and 70s.

But a new book claims that the legendary Polish journalist, who died three years ago aged 74, repeatedly crossed the boundary between reportage and fiction-writing – or, to put it less politely, made stuff up.

In a 600-page biography of the writer published in Poland yesterday, Artur Domoslawski says Kapuściński often strayed from the strict rules of "Anglo-Saxon journalism". He was often inaccurate with details, claiming to have witnessed events he was not present at. On other occasions, Kapuściński invented images to suit his story, departing from reality in the interests of a superior aesthetic truth, Domoslawski claims.

Domoslawski told the Guardian: "Sometimes the literary idea conquered him. In one passage, for example, he writes that the fish in Lake Victoria in Uganda had grown big from feasting on people killed by Idi Amin. It's a colourful and terrifying metaphor. In fact, the fish got larger after eating smaller fish from the Nile."

He added: "Kapuściński was experimenting in journalism. He wasn't aware he had crossed the line between journalism and literature. I still think his books are wonderful and precious. But ultimately, they belong to fiction."

On another occasion, the writer reported vividly on a massacre in Mexico in 1968. Although he was travelling in Latin America at the time, Kapuściński did not witness it, despite asserting "I was there", Domoslawski alleges.

The biographer, a correspondent with Gazeta Wyborcza, Poland's largest paper, said he did not want to debunk Kapuściński, whom he described as "my mentor". Instead, he said, he sought to start a debate over the relationship between truth and fiction, a biographer and his subject, and how far modern Poland remained haunted by its communist past.

"I think my book is fair. The strange thing is I was writing with sympathy about Kapuściński. I wrote it with big empathy," he said. Kapuściński's widow's, Alicja, however, has violently objected to the biography, entitled Kapuściński Non Fiction. Last week she sought an injunction in Warsaw's district court, arguing that the work damaged her late husband's reputation. (Four previous biographies painted him in an entirely flattering light.)

The court rejected her request. It pointed out that she knew Domoslawski was writing a biography and even allowed him to use Kapuściński's private archive. She has now appealed to the high court.

Domoslawski said he was baffled by her attempts to ban the book. The biography includes only 17 pages that dwell on Kapuściński's erotic relationships with women and examines claims that he collaborated with Soviet intelligence.

Born in Pinsk, in what is now Belarus, Kapuściński embarked on a career in journalism after university in Warsaw. In 1964 he became the only foreign correspondent of the Polish Press Agency, and for the next 10 years he was "responsible" for 50 countries. He travelled across the developing world during the final stages of European colonialism, witnessing 27 revolutions and coups.

He kept two notebooks – one for recording mundane facts used in reports relayed to Warsaw by telex, and another for impressionistic observations. These were to form the basis for his highly acclaimed books, among them The Soccer War, about the 1969 conflict between Honduras and El Salvador over a pair of football matches, and The Emperor, a brilliant study of the extraordinary and deranged Haile Selassie of Ethiopia. He also published Imperium, arguably the best study ever written on the fall of the Soviet Union.

Kapuściński achieved worldwide fame only in his mid-40s, when his works were translated into numerous languages and he was hailed by critics for his miraculous synthesis of private experience with wider historical patterns. Back at home Poles voted him journalist of the century.

Today Domoslawski said that Kapuściński had not only delved into fiction on many occasions, but had also mythologised his extraordinary life. "In part of his literary work he was creating a legend of himself. I can understand the reasons. If you come from a small country whose culture and language are not understood abroad, you make your message stronger."

He said he got to know Kapuściński during the last nine years of the writer's life. Domoslawski travelled extensively during the 1990s in Latin America, an area in which he and Kapuściński had a strong common interest. The idea of writing a biography only came to him after the journalist's death, he said.

"I would hesitate to call him my friend, since other people are entitled to say they were better friends than I was, but Kapuściński always treated me as a kind of disciple," he said.