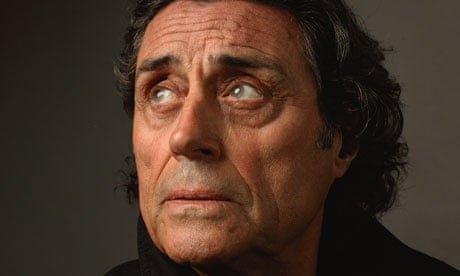

On a breezy spring afternoon in Santa Monica, Ian McShane and I are hauling furniture around a hotel room. The suite has been used recently for a photo shoot, and McShane has decided he wants everything back the way it was. I pull one of the sofas towards the fireplace, dragging the rug with it. He manoeuvres the other with surprising ease: he's a small but compact man, around 5ft 7in, sinewy, with a light mahogany tan; and although there is some grey amid the glossy black curls, it's very easy to forget that he is 70. "Seventy years old!" he rages in his distinctive Lancastrian burr, like syrup on sandpaper. "How did that happen? I was part of the generation that wasn't going to die."

Retrieving our drinks and sitting down on the newly positioned sofas opposite each other, we find that, if we both lean forward at the same time, our kneecaps are in danger of touching. I don't think McShane is much perturbed. His conversation can be rambunctious and matey, but he has a gentle manner, with none of the menace that fuelled the role for which he is now most admired: the late-18th-century brothel-keeper and bar-owner Al Swearengen in the pungent HBO western series Deadwood. He is also pleasingly un-showbizzy, which may be why he and his third wife, the actor Gwen Humble, chose nearby Venice Beach as their home 10 years ago. "It could be anywhere," he says approvingly. "It could be Brighton." As if to prove his point, the ferris wheel at the Palisades Amusement Park, visible from the window, completes another sleepy revolution.

He can be found here, when he's not flying back to England to visit his 92-year-old mother and his two children and three grandchildren. "I do as little as possible. Lots of walking on the beach. That's another great thing: no one owns the beaches. All those rich fuckers up in Malibu keep trying to get the public off it. They lock parts of it up. David Geffen tried it: 'Get orf my land!' I live on Venice Beach because it's for everyone." There are other selling points. "Practically the only roundabout in the whole of America is here! It's hilarious. No one knows what to do when they get to it."

This man-of-the-people routine is probably the aspect of McShane most prized by audiences, and it can't be a coincidence that his two signature roles have been flipsides of the same roguish persona, one charming (Lovejoy), the other infinitely scuzzy (Al in Deadwood). Today he's wearing a black windcheater jacket over a powder-blue T-shirt, dark blue jeans and black boots; an ensemble worthy of Lovejoy, the antiques dealer hero of the Sunday evening comedy drama that ran in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was a character McShane enjoyed playing so much that he turned down an $80,000-an-episode stint on Dynasty to keep doing it (though he did serve time as Sue Ellen's film-maker husband on its rival, Dallas).

Lovejoy was a big deal, with X Factor-sized ratings: McShane's easygoing charisma reeled in up to 16m viewers a week. He still gets approached by its fans, even in LA. "They love it here!" he hoots. "The antiques thing is so popular, isn't it? That dreadful David Dickinson said to me once, 'You're responsible for me being on the telly.'" He sucks the air through his teeth. "What an awful burden to bear."

In recent years McShane has been busy with a run of time-consuming, XL-sized special-effects blockbusters: Jack The Giant Slayer is only the latest after Pirates Of The Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, Snow White And The Huntsman and The Golden Compass. He is undaunted by their scale, and realistic about their shortcomings. Snow White, he says, was the most disappointing. "Six hours in prosthetics every day," he laments. "By the time you got on set, it was all crash-bang-wallop. It hadn't been properly worked out." He had fun making the fourth Pirates Of The Caribbean, up to a point, and still wears a chunky skull-and-crossbones ring from the film. "You'd finish a scene and someone would say, 'That turned out well!' And then you have to say, 'You know what's going to happen to it, don't you?'" He uses the whole of one arm to mime an enormous guillotine blade crashing down, and bursts out laughing. "They're not looking for subtle scenes of character-building. They don't make it in. You just enjoy it while you can."

On the plus side, he gets to take his grandchildren to these popcorn movies. "You can't exactly sit them down and make them watch Deadwood. I took them to the Pirates premiere. A premiere at Westfield." He gives an "I ask you" shake of the head. "You hear: 'Please welcome Gok Wan to the red carpet!' Christ, it was odd."

Jack The Giant Slayer is an attempt by the director Bryan Singer to bring some Lord Of The Rings-style rustic grime to the world of fairytales. Rather against type, McShane plays a softly spoken king. He gets a nice comic entrance – stepping out suddenly from beneath a vast coronation mantle to reveal how teeny-weeny he is. But you can't help asking, what was in it for him? "I wanted to play a good guy for a change. We filmed in England, so I got to see my family."

Though he first came to live in the US in the mid-1970s with his second wife, the model Ruth Post (mother of his two children, Kate and Morgan), McShane has not yet tired of arguing with it. "Funny old country. Do you follow American politics? They hate Obama. Hate him. He's a black man. That's what it is: it's racist. This guy is no bleeding-heart liberal. He's a centrist."

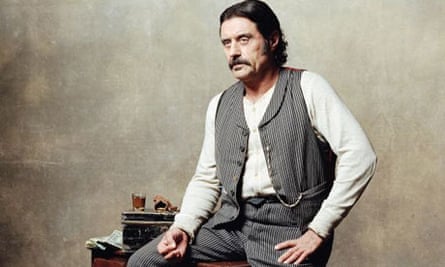

The development of America and capitalism has interested him particularly since he started making Deadwood in 2004. "What Deadwood did was to talk about how capitalism started, how civilised society came in and how that brought its own problems." It's not long before we are on to the subject of its cancellation after just three seasons. "It was tragic," he says, still sore. This was an unsavoury, profane and uncompromising show, with Al Swearengen personifying all those elements. But there was nothing so brutal as the manner in which it was snuffed out. It was all down to business, McShane says ruefully: the vagaries of a complicated production deal, not to mention the expensive manner in which the series was made, with the entire cast and crew based near the set (which reproduced a South Dakota gold-prospecting town), and creator David Milch often faxing performers their pages only hours before shooting.

"There was no script when you started," McShane says. "Everyone was staying at this ranch. If you liked acting, you could take a chance every single day." Accepting the Golden Globe for Best Actor for his work on the first season, McShane called it "the best gig I ever had", and he stands by that now. "I'll catch it on TV sometimes and get drawn in. It was not good. It was fucking brilliant."

Long before he first shrugged on Al Swearengen's stripy jacket and oiled his soup-straining moustache, McShane had always had his pick of cads and roister-doisters. A typical McShane bounder could be a savage or a sophisticate; he could just as easily be straight or gay. He is masculine but defiantly anti-macho, and his unpanicked air of sexual fluidity has lent itself to a run of gay gangsters: he was Richard Burton's bit of rough in Villain, a carnally carnivorous mob boss in Sexy Beast, and a slinky, elegant hood in 44 Inch Chest.

At the start of his film career, McShane was one of the rakish young blades of 1960s British cinema. Check him out with a springy, teddyboy quiff, causing a fracas on the dancefloor in his first film, The Wild And The Willing, from 1962, or as a smouldering gypsy in 1965's Sky West And Crooked. ("Hayley Mills!" he coos now. Then, affectionately: "I gave her her first screen kiss.")

McShane had to skip his last term at Rada to make The Wild And The Willing. "They told me, 'If you do this film, you might not get your certificate.' What, I need a bit of paper on the wall telling me I'm an actor?"

Still, they gave it to him in the end. "Signed by John Gielgud! I spoke to him about it much later on when he did an episode of Lovejoy. I said, 'Thanks for signing my Rada certificate, John.'

'Ooh, dear boy, not at all…'

He kept calling me Loveboy. 'Loveboy, I say…'

'Um, John, it's Lovejoy.'

'Lovejoy, Loveboy, who cares?'"

He has fond memories of Rada but acting is a profession he wears lightly: he sees no need to suffer demonstrably for his art. "Ian McKellen will tell you that the theatre was in him. Well, it wasn't in me. I love acting – it's been very good to me – but it wasn't in me." A teacher spotted that the 14-year-old McShane had talent, and steered him into some ambitious school productions. "I thought, 'I can do this. I mean, I wish I was better at football, but I can do this…'"

The football comment is not a throwaway one: he is the only child of Harry McShane, who had already played for Blackburn, Huddersfield and Bolton before becoming part of Matt Busby's legendary league-winning team of Manchester United's 1951-52 season. I imagine the cachet at school must have been tremendous, but he puts me right on that. "Dad was definitely significant. It meant something. But it was a different time, you know? We were living in the suburbs in Manchester, in a typical footballer's semi-detached house." His father never pushed him towards football. "Mum and Dad were both happy for me to do what I wanted. I took them to the premiere of The Wild And The Willing. I said, 'It's not bad, is it, Dad? It's not Old Trafford, but it's the Empire Leicester Square.'"

While forging a film career in the 1960s, McShane was working in theatre, too, though he seems to have felt slightly less at home there: "When I was coming up, theatre directors were all called Peter and they'd all gone to Oxford or Cambridge, and I thought they were all fucking useless." He was in the original 1965 production of Joe Orton's Loot, playing Hal, the impish hero who hides the proceeds from a robbery in his mother's coffin. "Joe and I used to go out drinking together," he recalls. "He was incredible. Indefatigable. He kept getting picked on by Kenneth Williams, who was in the cast, and the director Peter Wood – another bloody Peter. They'd tell him, 'This isn't funny!' Joe would go away and write and come back with 12 new pages. If they didn't like that, he'd do 12 more. They couldn't keep him down. You forget how shocking the play was. We got booed in Bournemouth. In Manchester, the theatre owner asked me, 'Aren't you ashamed to be in this?'"

He says he still enjoys theatre – when the ingredients are right. "Not when you've got three leading ladies who hate each other." He's referring to the ill-fated West End production in 2000 of The Witches Of Eastwick, in which he played the Jack Nicholson role of "horny devil" Daryl Van Horne. "I had a great time. Probably the show wasn't dirty enough."

Such minor blips aside, McShane's career has remained remarkably even since the 1960s. There are peaks, such as Lovejoy and Deadwood, and there are quieter passages, creatively-speaking, such as the mid-1970s ,when he concentrated on becoming a professional party animal. "I was disenchanted with a lot of things," he reflects. "I was in a marriage at the wrong time. It's been gone over, but I think I was busting out. I had been playing the good boy too well. Coming to the US, I thought, 'I've been working for 10 years and now I'm going to have a good social life before it's too late.' It was perfect timing: the 1970s! I just thought, 'I don't want to discover the fruits and dangers of life when it's too late. I don't want to be like Willie Donaldson, doing crack when he's 65.' Not that I did crack..." Vodka breakfasts and cocaine, yes, but no crack. He left his children's mother for Emmanuelle star Sylvia Kristel, with whom he had a brief, hedonistic, tempestuous relationship with violence on both sides. Drugs and drink consumed him for many years, but he kicked both shortly after meeting and marrying Humble in the 1980s.

One constant was his relationship with his parents, at least until last November, when his father died after suffering for seven years from Alzheimer's disease. McShane looks shaken when he talks about this. Mostly, though, he glows with pride when he talks about Harry McShane. "Ah, he was great. We never had a row. Which is why, when he died, even though it wasn't unexpected, well, it's still your Dad. It doesn't matter how old you are. You've lost your Dad."

There's one memory of his father in particular, from just before he had to go into a nursing home, that makes his face light up. He sits forward to tell me, so we are as close as commuters on a crowded train. "He still recognised my mother when he was ill. It was amazing. Because it was a love story, you know? They were together more than 70 years. And he half-recognised me. I walked in and he said, 'Who are you playing for nowadays?' I said, 'Dad, now look: you're the footballer, I'm the actor.' He said, 'Oh.' And then he said something that put me right in my place. His timing was incredible. He looked right at me and said, 'Would I have seen you in anything?'"

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion