The Budokwai is the oldest and most famous Japanese martial arts club in Europe. For a century, the club has been both a beacon of excellence and a prime mover in their development. It played a leading role in the establishment of the European Judo Union (EJU) and the International Judo Federation (IJF).

Some of the most distinguished figures in the history of the Japanese martial arts have trained or taught at the Budokwai, including many Olympic medallists. Although primarily a Judo club for much of in its early days, it now embraces Shotokan Karate, Aikido and Gracie Jiu-Jitsu.

The Budokwai was founded in 1918 in Lower Grosvenor Place, along the back wall of Buckingham Palace, by Gunji Koizumi, a Japanese immigrant, who thought the promotion of Jiu-Jitsu and Ken-Jutsu (sword fighting) might help his adopted country, then immersed in the First World War.

Koizumi subsequently wrote;

"I hoped that rendering my service in promoting such training would be a means of pacifying my conscience, which was pricked by the fact that we Japanese, especially students, had been recipients of the kindness and hospitality generously bestowed by the people of this country, without making any tangible return."

The Budokwai was founded on the ground floor and basement of what had been a German dressmaker. Work on redecorating the premises began in December 1917 and the club officially opened on Saturday 26th January 1918, with improvised judogi (suits) and 12 members. Koizumi adopted the name of the club or, strictly speaking, society, in the following manner: 'bu' meaning martial or military, 'do,' way or code and 'kwai' meaning society. He explained:

“The society badge was designed, the character ‘bu’ on the background of a cherry blossom. Bu is composed of two characters, one meaning spear or fighting, the other meaning stop, indicating that the aim of martial training is to stop fighting.”

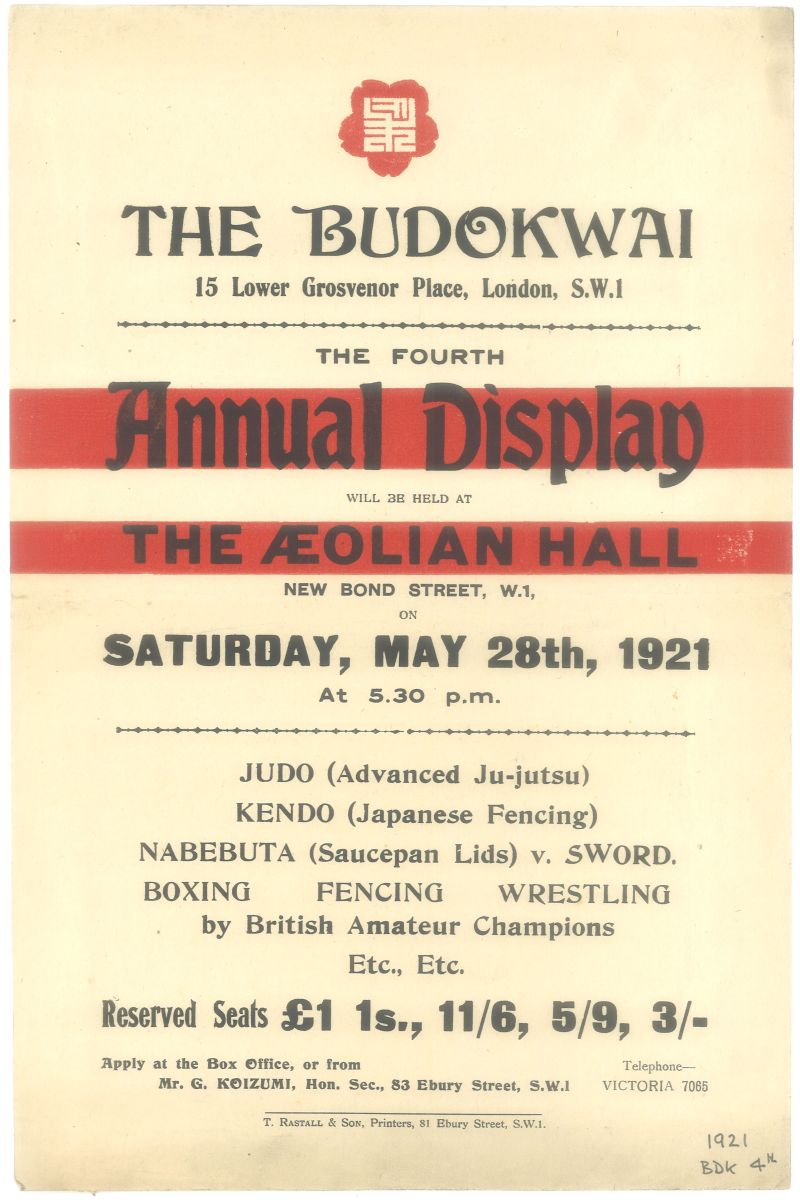

An early tradition was the club’s annual show, the first of which was held at the Budokwai on May 11, 1918 and attended by the Japanese Consul-General. By the end of the first year, the number of members had risen to 54 and the following June, there was the inaugural general meeting of the club. There were three main principles:

The Club Principles were established on May 11th 1918:

- In pursuance of Judo, be earnest, sincere and open-minded for mutual assistance.

- Treasure chivalry, despise cowardice and esteem straight living.

- Never boast of, or misuse, one’s skill in Judo or other arts.

1920 proved a significant year because, to cope with the increasing demand for instruction, Yukio Tani was invited to be an instructor at the Budokwai. He joined by Hikoichi Aida, who had accompanied Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo, in a visit to Britain that year and stayed as an instructor until 1922. This began the link between the Kodokan, the headquarters of the sport in Tokyo, and the Budokwai. During the 1930s, there were even attempts to merge the Budokwai with the Kodokan, creating a London branch of the Kodokan but this was eventually abandoned.

By this time, Judo was already becoming a wider activity than just a martial art confined to links with Japan. In 1926, the Budokwai had taken part in the first international match against Germany. The interest in the activity was growing with the Budokwai featuring on television in August 1937, less than a year after the BBC had started the first television service world.

As a result, there was less and less time at the Budokwai for such ancillary activities as practising kata, producing magazines, having lectures on the Japanese way of life and the history of the country, katsu classes and particularly the rehearsals for the annual show. The display was held regularly for the last time in 1968, when Anton Geesink, the Dutchman who won the first Olympic Open title in 1964, did the famous 10-against-one line-up. However, the show has been revived for special occasions, such in 1988, when the club celebrated its 70th anniversary.

Another change occurred in the mid-1960s when the Budokwai began its link with the Japan Karate Association (JKA), the predominant Shotokan organisation. First, with Charlie Mack and subsequently with a number of Japanese, notably Keinosuke Enoeda, the 1963 All-Japan champion, karate became increasingly an important feature of the club’s activities, with classes in the martial art eventually being staged on six days of the week. National shotokan karate championships began in 1967, two years after the JKA had sent over four missionary instructors, including Enoeda and also Hirokazu Kanazawa, the 1957 and 1958 All-Japan champion.

Aikido became another important feature of the club’s curriculum with the return of John Cornish from Japan in the same decade, while Gracie Ju-Jitsu has been introduced more recently.

The pressure on getting mat-space for the different activities as well as the varied level of ability in those activities grew steadily, particularly since there was the additional demand of martial arts for children. Week-ends began to be used even more extensively than previously. Judo gradings, which once used to stop most activity in the club for a week every three months, were eventually shifted to Sundays, so leaving week-days free for practice.

After being omitted from the Mexico City Games of 1968, men’s Judo became a regular part of the Olympic programme in 1972, largely thanks to Charles Palmer, a member of the Budokwai, former national team captain and the first non-Japanese president of the International Judo Federation. He had campaigned assiduously for Judo’s inclusion in the Games and his satisfaction at the success of his efforts further increased when Britons won three medals in Munich.

Two of the fighters were from the Budokwai: middleweight Brian Jacks, who had won Britain’s first medal at a world championships when he finished third in Salt Lake City in 1967, and the other by Angelo Parisi, who took a bronze medal in the Open Class at the age of only 19 years-old and, after changing his nationality to French, collected three further Olympic medals, including the heavyweight gold in Moscow in 1980.

Of even greater long-term benefit for the club during the 1970s was the buying of the freehold of the club’s premises, something that not only saved money in rent but also, because of the increase in London property prices, provided a financial buttress for the club’s future. As the monetary reserves steadily improved over the following 30 years, leading competitors also began to receive subsidies from the club to help them prepare for major events, something that had become a full-time occupation.

Competitors such as Neil Adams, who arrived at the club in the 1970s and, in 1981, became the first British male world champion, and Ray Stevens, who won a silver medal in the 1992 Olympics, were an example of this trend. Until the 1960s, it was difficult, although not impossible, to get into the British team unless a fighter had either lived in London and/or had spent time training in Japan. However, as the sport grew in popularity and clubs outside the capital became stronger; neither practice became essential for international success.

Although no longer dominating the sport as it had done, the Budokwai continued to play a significant role in British judo, supplying members to both the men’s and women’s national squads up to the present day. They were aided in this by a revival in the practice of inviting Japanese instructors to teach at the club. After Kisaburo Watanabe had left the club in 1966, there was a gap until Katsuhiko Kashiwazaki, the 1981 world featherweight champion, arrived in 1982 with his remarkable facility for newaza (groundwork) techniques. He was then followed by a series of celebrated instructors, none more so than Yasuhiro Yamashita, the 1984 Olympic heavyweight champion and the man who did so much to restore his country’s pre-eminence in the sport after it had suffered several maulings, especially in the heavier categories, during the 1970s.

In recent years, the club has continued to expand in numbers, particularly among juniors in Judo, and also in Karate, despite the death in 2003 of Keinosuke Enoeda, who had been the chief instructor. The links with the Japan Karate Association have remained strong. As a result, at the start of the 21st century, the Budokwai has maintained its position as the leading Japanese martial arts club in Britain. It is financially secure, enjoys a large membership, has recently renovated premises and, above all, possesses a status against which all other clubs in the United Kingdom are measured.

Thank you to the, Bowen Collection, The Library, University of Bath, for the kind use of the historic images on this page.

For digitised copies of British Judo magazines and some of the Budokwai Quarterly magazines, dating back from the mid 1950s see here, with thanks to Jerry Hayes, Paul Gordon and David Finch.

See the digitised copy of Twelve Judo Throws and Tsukuri, first published by the Budokwai in 1938, via the following link: Twelve Judo Throws