Dr. Sanjay Gupta has been following the 2011 season of a North Carolina high school football team. In 2008, a player on the team died after sustaining a head injury during a game. For a closer look at the health and safety issues on the playing field, watch “Dr. Sanjay Gupta Reports: Big Hits, Broken Dreams,” this Saturday night at 8 p.m. ET.

Story highlights

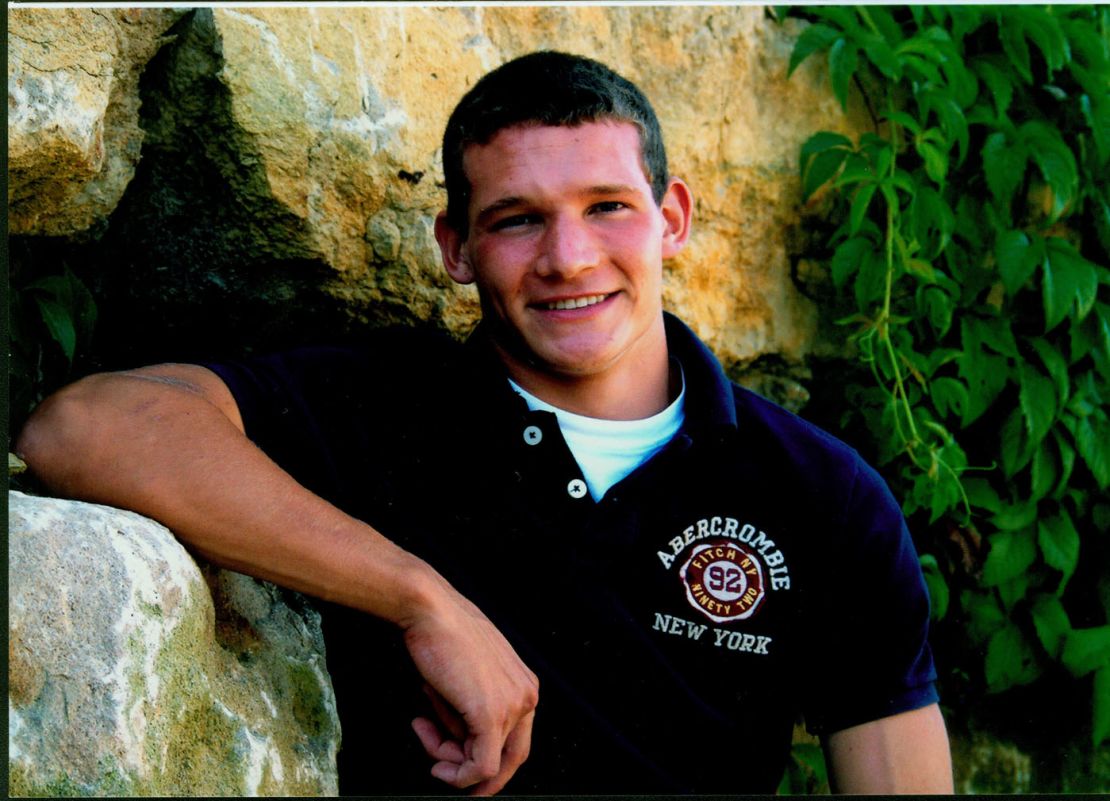

Nathan Stiles was the youngest reported case of chronic traumatic encephalopathy

The degenerative disease is found in athletes who get repeated blows to the head

VA Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy Brain Bank examines injuries

For 17-year-old Nathan Stiles, his senior year was supposed to be the best yet.

He was a straight-A student and homecoming king at Spring Hill, Kansas, High School, and was the Broncos’ star running back. He was a starter on the varsity basketball team and loved to sing at church. He was the son any mother dreamed of having.

His mom, Connie, recalls, “He was an athlete, but school was important. His grades, his teachers and just having a family … he had his priorities right.”

The final game of his senior year turned out to be the final game of his life. Nathan died playing the game he loved, football. His autopsy would reveal he died of second-impact syndrome, when a player is hit again before the brain has had a chance to heal from an initial concussion.

But it would turn out that those repetitive hits Nathan took on the field would also make him the youngest reported case of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). It’s a degenerative disease found in football players and other athletes in contact sports who get repeated hits to their heads.

The day after homecoming, Nathan complained of headaches. But nothing unusual, until five days later, when his mom received a call from his athletics trainer. “Nathan’s telling me he’s still having headaches. You need to go take him to the emergency room.’”

And so Connie did. Nathan had a CT scan and the doctors reported a clean bill of health. Yet, to be on the safe side, doctors kept him out of play for three weeks.

Kansas is one of 34 states that require a player to be cleared by a health care professional before they return to play. In addition, Kansas also requires that players and their parents sign a waiver acknowledging the risks of concussions.

When Connie and Nathan returned to the doctor’s office three weeks later, Connie remembers Nathan turning to her and asking “Now, Mom, are you OK with this?” She didn’t want him to, but it was hard for her to say no. “You know, it’s his choice,” she said.

His first game back, Connie remembers him getting hit. “I saw him kind of get stunned. But he walks out and tells Ron, ‘Oh I’ve never felt better, that was the best game, I never felt so good.’” He even took his ACTs the following day and had no complaints. The headaches that had bothered Nathan several weeks before were gone, or at least appeared so to his parents.

The following week was the final game of his career. Nathan intercepted the ball and sprinted toward the end zone. Touchdown. “If you would watch him run, he had a flow about him that was just beautiful. I mean it looked so graceful,” remembers his dad, Ron.

But right before halftime, his parents noticed Nathan was acting strangely. “I watched him walk off the field, and I said, ‘He’s walking funny.’ I mean, I know that kid so well,” said Connie. Her phone rang. It was someone on the bench by Nathan.

“Get over here. Something’s wrong,” she heard.

By the time Ron and Connie made it to the bench, it was too late. Nathan had collapsed on the sidelines. His mother rushed to his side, trying to get him to wake up. “Come on buddy, it’s your mama, come on!” she urged. But instead of waking up, Nathan began seizuring.

He was airlifted to The University of Kansas Medical Center, some 50 miles away, and rushed into surgery. Four hours later, the doctors came out to tell Ron and Connie they stopped the bleeding in his brain, but Nathan’s lungs and heart were too weak to go on.

By 4 a.m. the following morning, Nathan was off life support.

Nathan’s autopsy revealed he died from multiple hits to the head, also known as second impact syndrome. As Ron and Connie tried to determine what was next, Ron received a call he never expected. “You know when you get a telephone call after your son dies saying they want your son’s brain, sometimes that’s a hard call to get.”

On the other end of the line was Chris Nowinski, one of the co-directors of the Boston University Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy. The center works with the VA Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy (CSTE) Brain Bank, and together they work to understand what those hard hits on the field are doing to the brain, by looking inside the brain.

Nowinski spends his time tracking football and sport related deaths and having to make the difficult calls to their families. “I have called hundred of families within 48 hours of their loved ones dying, and it’s never easy.” Instead he focuses on the fact that the bank’s work will protect families in the future. “I hate every call we make, but you know, I honestly, I have to prep and think of the positives that come out of it.”

The Brain Bank is the world’s largest collection of athlete brains. Since its inception in 2008, the bank has documented more than 50 cases of CTE. Much of that work is in the hands of Dr. Ann McKee, the bank’s director and neuropathologist. She actually dissects the brain to track the trauma, and what she’s finding in the brains of some players in their 40s and 50s is astonishing.

“You expect a pristine brain. I saw a brain that was riddled with tau proteins. I was stunned at how similar that brain was to the boxers who lived into their 70s,” she said. Tau proteins are the same type of proteins found in brains of Alzheimer’s patients.

But to see the same type of damage in 17-year-old Nathan Stiles’ brain was something that surprised even McKee. It’s the youngest case she’s documented, and for her that was a call to action. “It tells you that we’ve really got to protect our kids,” she said. “It’s not just car seats and seatbelts, but it’s making sure that when they go out to play sports that we take proper precaution and we give them proper advice.”

And that means making sure that athletes take the time to recover from concussions, and making sure they aren’t playing symptomatic, while having headaches or memory problems.

For Ron and Connie Stiles, the findings and the warnings were too late to save their son. But Ron knows that Nathan’s legacy will live on as researchers learn more about concussions and how to treat them.

“I think there are some issues that need to be looked at, and I think that’s happening,” he said. “And I think that Nathan is helping that.”