OKABENA — The year was 1933, and in the midst of the Great Depression, a slew of bank robberies swept the Midwest, and Minnesota was not immune.

Newspaper headlines in bold black letters tell of five gunmen robbing First National in Brainerd; $5,000 is taken from a Starbuck Bank.

And in May of 1933, in the southwestern Minnesota city of Okabena, a team of four — two men, two women — made away with nearly $1,400 from the First State Bank of Okabena.

In the coming years, three people would be tried and convicted for this crime. Three people who, after two years of research, St. Cloud State University Professor Brad Chisholm believes didn’t have a thing to do with it.

May 1933

ADVERTISEMENT

In the early morning of May 19, 1933, two men broke into the First State Bank of Okabena using a rear window and waited seven hours for the bank’s employees to show up. When they did, the cashiers were held at gunpoint and made to open the safe, which the intruders took nearly $1,400 — the equivalent of $23,000 in today’s cash.

While the safe was emptied, six people entered the building. Each was ordered to get onto the ground and lie there, before being forced into the basement so the bandits could escape — but not before the chief cashier triggered the “silent” alarm, alerting the next-door hardware store to the crime being committed.

With their loot in hand, the robbers exited the bank through the back door and climbed into a black car with two women. One was the driver. The other was a gun-toting red-head, who didn’t hesitate to exchange bullets with the hardware store owner who opened fire during their escape.

The car sped off, its three passengers spraying bullets as they tore through the town, and towards the Iowa border, 20 miles away.

It had only taken fifteen minutes. Four people, one getaway car, and thankfully, no injuries — but in the nearly 90 years since it happened, two theories have prevailed about the identity of the Okabena bank robbers.

Conflicting narratives

One theory is that brothers and petty criminals Tony and Floyd Strain robbed the bank before making their escape in a vehicle driven by Mildred Strain, Tony’s wife.

All three Strains were tried, convicted and served time for the Okabena robbery. The fourth member of their party — a mysterious, gun-wielding woman named in a Jackson County warrant as "Belle McLain" — was never found.

ADVERTISEMENT

The second theory is that prolific Great Depression-era bandits Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow robbed the bank that May morning, with the help of Clyde’s brother Buck and his wife Blanche.

The foursome then tore through the streets of Okabena, leaving a hail of bullets behind as they raced to the Iowa border, not twenty miles south of the town they’d just robbed.

While both theories uphold the suspense, mystery and flair worthy of a 1930s crime epic, only one can be true — and despite the long-held local belief that the Strains committed the bank robbery, upon publishing his research in 2010, Chisholm is certain that the tale that ended with the culprits behind bars is the work of fiction.

A research project

A film studies professor at St. Cloud State University, Chisholm first began looking into the Okabena bank robbery as a more homegrown angle for students seeking to research the bullet-riddled gangster-glory era of the 1930s that they normally saw on screen.

“When I heard about the controversy over a bank robbery from the Depression era, I thought, okay, I can come up with a research project that makes my students look into an actual bank robbery and compare it with the Hollywood versions of crime stories that were popular in that decade,” Chisholm explained. “But the more I looked into it, the more I wanted to get to the bottom of it.

"And so I deviated from any real film study work in that project in order to solve the mystery," he said. "I was just so hooked... there was this controversy, and people on both sides of the issue were very adamant that their interpretation of what happened was right.”

He spent the next two years researching the Okabena bank robbery.

ADVERTISEMENT

Chisholm read newspaper coverage of the incident, accessed prison records for Tony, Floyd and Mildred, and pored over court transcripts from their respective trials. After a few months, he had gathered up a long list of people involved — from investigators, jury members and prosecutors, to witnesses of, by that point, a nearly 80-year-old crime.

Then, he sent letters.

“I just went to Minnesota, South Dakota and Iowa phone books,” Chisholm said, “and I identified people with the same last name in about a 200-mile radius and then I wrote letters. It's a real long-shot, needle-in-the-haystack approach.”

But it worked. Chisholm received responses from descendants of all sorts of people involved in the case, who were able to pass down families' stories tying back to that day in 1933.

There were written accounts of the crime left in journals and an audio recording from someone’s grandmother, describing the bank robbery. Chisholm even spoke with someone who had witnessed the robbery in Okabena, back when they were a schoolchild.

He spoke with people who knew the Strain family too. Among them was a brother of Mildred’s, who wound up being one of Chisholm’s best contacts, and the daughter of one of Floyd’s ex-wives, who recounted how, at family reunions, Tony Strain would tell the story about how he did time for Bonnie and Clyde.

Debunking a local tale

In her 2005 memoir “My Life with Bonnie and Clyde,” Blanche Caldwell Barrow writes about a robbery she pulled off with the Barrow Gang, in an unnamed town.

ADVERTISEMENT

The details, down to the weather the night before, are all a match for the Okabena bank robbery — perhaps the strongest piece of evidence, to Chisholm, that the Barrow Gang were the true bandits of the Okabena heist.

“There’s no doubt at all,” said Chisholm, on the question of whether the Strains could have done it. “I asked myself that question a lot…I wanted to be absolutely certain that I got it right, so every time I saw a mention of the Strains, I went back and double-checked.”

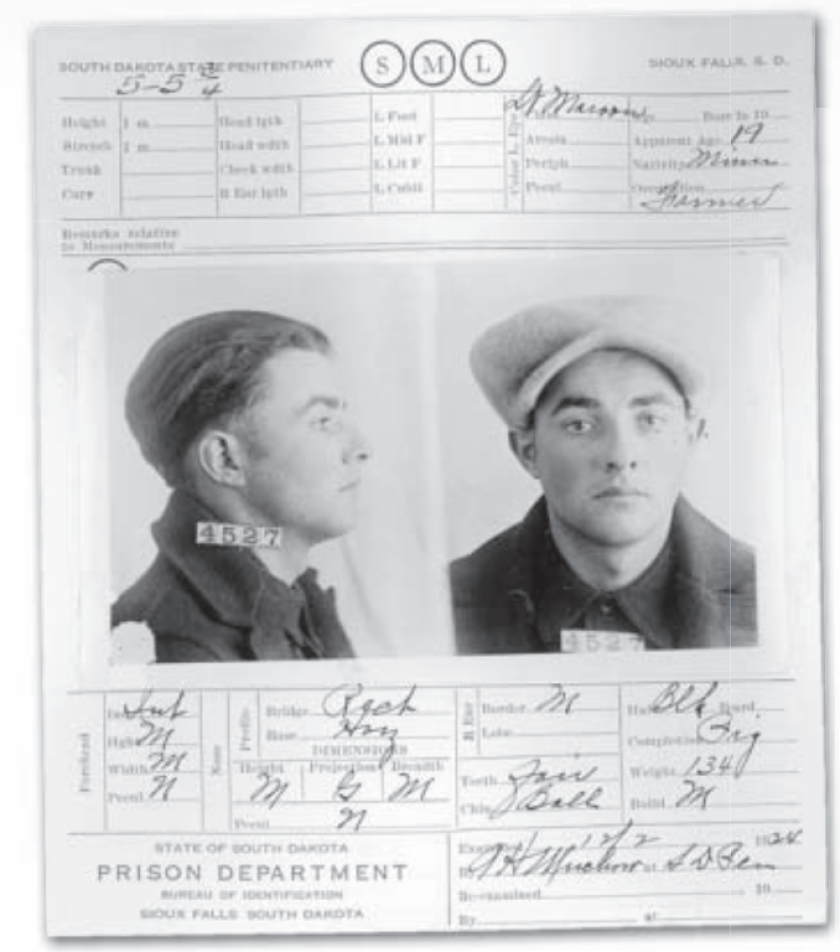

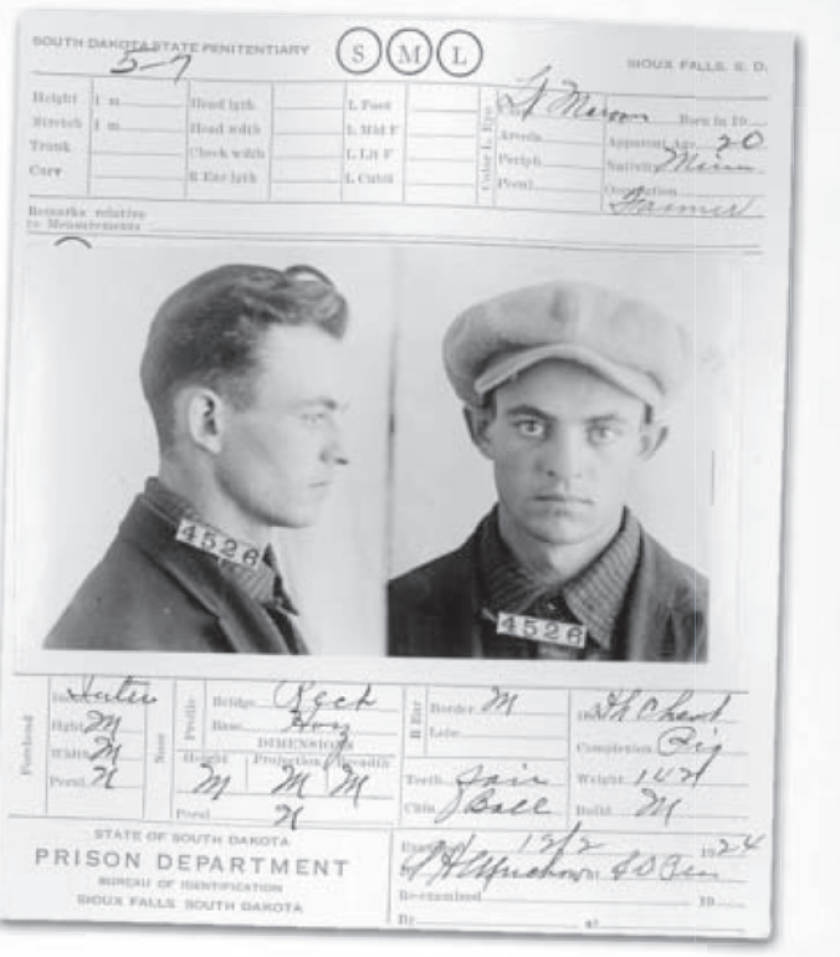

What he found, was that the Strain brothers and Mildred had very clear alibis. Tony and Floyd Strain were a pair of petty criminals. Floyd had been divorced several times, and Tony had married Mildred — an ex-con herself who had dabbled with a bank robber boyfriend in the past.

On the day of the Okabena heist, the Strain brothers claimed they had been delivering illegal shipments of liquor in Rapid City, South Dakota, and their landlady attested that Mildred was at home during the robbery. Their less-than-reputable standing in the community and law enforcement's declaration that their alibis weren’t credible did the Strains no favors.

“Tony and Floyd lived a shady life,” Chisholm said. “I mean, they weren't law-abiding citizens. Floyd was a check fraud. He was a wife-beater. He made illegal booze himself. He hung out with car thieves, although I don't have any evidence that he ever stole a car himself. They were all questionable people.”

It didn’t help that police had publicly tied the Strain brothers to another handful of robberies — all later solved, without any indication the Strains were ever involved. But the damage had been done, and the jury declared Tony and Mildred guilty after just one hour of deliberation.

It also didn’t change the fact that Mildred, the supposed get-away driver, didn’t know how to drive, which she admitted to on the stand. During their conversations years later, Mildred’s brother confirmed this for Chisholm. She couldn’t have been the one behind the wheel.

And of course, there was the mysterious character of Belle McLain, the redheaded woman in the “Strain Gang."

ADVERTISEMENT

“For many months, I was trying to get to the bottom of ‘Who the hell is Belle McLain?’,” Chisholm said. “She is identified in the indictment as the fourth woman there, a reddish-haired woman that was sitting in the passenger seat wielding a machine gun.”

He goes on to note that this was in reality, almost certainly Bonnie Parker — because Belle McLain never actually existed.

Floyd was a colorful character, with no shortage of girlfriends. The McLain name was initially released by prosecutors in a press conference as an alias for one of Floyd’s ex-wives, and Helen Roder was thought to be the mystery gun-woman — a theory that Chisholm said started and ended with her having reddish hair, and a connection to the Strain brothers.

But Roder had divorced Floyd years before and had him arrested for child abandonment. She’d since remarried and was living in St. Paul with her new husband and kids.

“She was a suburban mom at that point, who hated Floyd,” Chisholm laughed, stating that prosecutors likely discovered that as well. He surmised "Belle McLain" was probably the result of pulling names from some of Floyd’s female associates and hoping one of them would stick as the fourth member of the "gang."

Female gang members were rare, and due to the high number of bank robberies at the time, prosecutors were eager to make the charges against the Strains stick.

“I think the prosecutors ultimately figured out that they were wrong,” Chisholm said. “But they chose not to inform the judges or the jury that Belle McLain was just a misnamed person who was clearly was not involved in the bank robbery anyway. And so they purposely let that misinformation go out there because they had to have some sort of answer.”

So, when the Strains went to trial — Tony and Mildred in 1933 and Floyd in 1936, due to being tried and later released in connection with a separate robbery — details like Mildred’s inability to drive and the non-existence of Belle McLain were swept aside, and the so-called “Strain Gang” was convicted of the Okabena bank robbery. In reality, they were two petty criminals, a getaway driver who never learned to operate a vehicle, and a mystery gun-woman who was more fiction than fact.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The jury did very contentious work,” Chisholm said. “None of the citizens of Okabena wanted to pervert justice. I don’t blame anyone at all, other than out-of-town prosecutors who just wanted the Strains behind bars. I’ve met people on both sides who very strongly believe it was the Strains or it was Bonnie and Clyde. It’s funny how muddy history can get.”

Chisholm’s article was published in the Minnesota History Magazine Winter edition for 2010-11, and he remains certain that the Barrow Gang robbed Okabena that day in 1933. While as far as he knows, the state of Minnesota still legally views the Strain brothers and Mildred as the perpetrators of the Okabena Bank Robbery, Chisholm says he feels he’s cleared their name in the eyes of history.

Not long after publishing, Chisholm recalled receiving a letter from Mildred’s brother, thanking him.

“He said, if Mildred was alive, she would be so happy because she spent her whole life trying to vindicate herself from this accusation, for which she served time and everything, but she was never able to get satisfaction in her lifetime, that anybody would ever believe her,” Chisholm stated. “But, you know, it made him so happy that her name could be cleared, at least by history. And so that made it, in a way, the most important research I've ever done in my career.”